Sjogren's Syndrome

Top Contributors - Cassie Shay, Kim Jackson, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, 127.0.0.1, Wendy Walker, WikiSysop and Sehriban Ozmen

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Sjogren's syndrome was first described by physician Henrik Sjogren in the early nineteen hundreds to explain the signs and symptoms of a group of women exhibiting chronic arthritis along with extremely dry eyes and dry mouth[1]. It is now understood that Sjogren's syndrome is an autoimmune connective tissue disease in which the body's own immune system attacks moisture-producing glands, causing inflammation in addition to a reduction in both the quality and quantity of the glands' secretions[1]. As observed by Dr. Sjogren, the glands responsible for producing saliva and tears, the salivary and lachrymal glands respectively, are the organs most notably impacted by the disease[2]. However, Sjogren's syndrome is a systemic disorder in which many organs may be affected, including kidneys, gastrointestinal tract, blood vessels, respiratory tracts, liver, pancreas, and central nervous system[3]. Additionally, it is considered a rheumatic disease, like rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, and similar to these diseases Sjogren's syndrome can cause inflammation in joints, muscles, skin, and other organs[2].

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Sjogren's syndrome is the second most prevalent autoimmune rheumatic disease. In 2008, it was estimated that 1.3 million Americans were affected[2][3]. Statistics from rheumatology clinics indicate that Sjogren's syndrome affects 0.5 - 1% of the general population and approximately the same number of people have been diagnosed with Sjogren's syndrome and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus[4].

Although, it can affect individuals of all genders and ages, including children, symptoms usually occur in women between the ages of 45 and 55 years old[1]. In fact, it is estimated that nine times as many women are affected when compared to men[3]. Among individuals with rheumatoid arthritis or systemic sclerosis, thirty percent have histological evidence of Sjogren's syndrome[3].

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

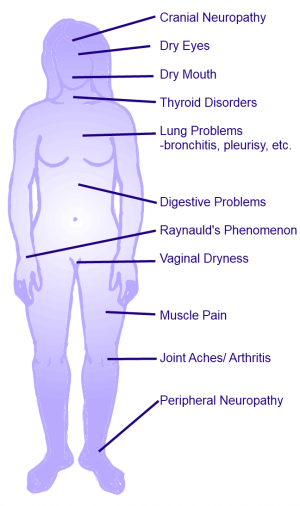

Patients with Sjogren's syndrome (SS) can present with a number of complaints. However, the most common symptoms of this autoimmune disease are dry mouth and dry eyes. These complaints may be considered mild in comparison to the symptoms commonly associated with other autoimmune diseases, such as rheumatoid arthritis. However, the dry eyes and dry mouth associated with Sjogren's syndrome can be quite severe. In SS, the extreme dry eyes is called keratoconjunctivitis sicca (KCS)[4], and individuals may describe it as a dry, burning, or gritty feeling, as though they have sand in their eyes[1][3]. The excessive dryness in the mouth, also known as xerostomia[4], may make it difficult to speak, swallow, chew, or it may make foods taste differently[3].

While these are the hallmark signs of Sjogren's syndrome, 40 to 60 percent of individuals with primary SS will develop extra-glandular problems[4]. A patient may present with a number of other complaints including:

- Joint and muscle pain[1][2]

- Fatigue[1][2]

- Skin rashes[1][2]

- Extremely dry skin[1][2]

- Dry eyes

- Weakness[1][2]

- Numbness[1][2]

- Digestive problems [1][2]

- Raynauld's phenomenon[1][2]

- Vaginal dryness (females) [2]

- Pain with intercourse (females)[2]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Approximately half of the patients who have been diagnosed with Sjogren's Syndrome have also been diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or some other connective tissue disorder[1]. Fewer people may also experience Sjogren's in association with lymphoma[1]. As more research is developed on the topic, more and more co-morbidities are being associated with SS. Recent studies suggest that clinical depression is also common among individuals diagnosed with this disease[2].

Secondary Sjogren's is a form of the syndrome which develops after the presentation of a primary disease, usually another autoimmune connective tissue disease[2]. Common primary diseases associated with Sjogren's Syndrome are listed in the table below.

| Disease | Description |

|---|---|

| Polymyositis | Inflammation of muscles that cause pain, weakening, and difficulty moving. If the skin is involved too, it is called dermatomyositis. |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | Severe inflammation of the joints caused by the body's own immune system attacking the synovium located throughout the body. |

| Scleroderma | Accumulation of too much collagen, resulting in thick, tight skin, and possible damage to joints, muscles, and internal organs. |

| Systemic Lupus Erythematosus | An autoimmune disease in which the patient may experience joint pain, muscle pain, fatigue, weakness, skin rashes, and possibly even heart, lung, kidney, and nervous system issues. |

| Lymphoma | Although rare, there is a small percentage of individuals with Sjogren's who also have lymphoma, which is cancer of the lymph system. This can affect salivary glands, lymph nodes, the gastrointestinal tract, and lungs. |

Medications[edit | edit source]

There is no cure for Sjogren's syndrome, therefore its symptoms are managed through medications, both prescription and over the counter. A variety of medications may be used to treat each of the associated symptoms.

| Drug category | Signs/ Symptoms Treated | Examples of Brand Names |

|---|---|---|

| Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

Joint and Muscle Pain | Ibuprofen |

| Corticosteriods |

Inflammation of lungs, kidneys, blood vessels, or nervous system | Prednisone |

| Immune-modifying drugs |

Overactivity of the immune system | Plaquenil (hydroxychloroquine), Rheumatrex (methotrexate), Cytoxan (cyclophosphamide) |

| Artificial Tears |

Dry Eyes | Clear Eyes, Visine Tears, etc. |

| Ointments (for night use) |

Dry Eyes | GenTeal, Systane |

| Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose |

Dry Eyes | Ocucoat |

| Topical steroids |

Dry Eyes | Restasis (cylcosporin A) |

| Saliva substitute |

Dry Mouth | Oralube |

| Cholinergic Agonists |

Dry Mouth | Salagen (pilocarpine), Evoxac (cevimeline) |

This table was created using information from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases[2] and PubMed Health[5], see references below.

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values [edit | edit source]

Diagnosis of this disease is based on medical history, a physical exam, and results from some clinical and laboratory tests[1][2][3]. Due to the nature of the disease in that the symptoms are similar to other diseases and they appear gradually over time, it may take years for Sjogren's to be properly diagnosed[2]. Nonetheless, diagnostic testing may include the following:

- The Schirmer's test assesses the function of the lacrimal glands by measuring the amount of tears they are producing. This test involves putting a strip of paper under the lower eyelid, waiting five minutes, then measuring how much moisture was absorbed by the paper. An individual who tests positive for Sjogren's syndrome will typically produce too few tears to get more than 8 millimeters of the paper wet[2].

- During a slit lamp examination, an ophthalmologist magnifies and examines the eye for severe dryness and inflammation. This test may be performed in conjunction with a vital dye applied to the eyes to determine the extent to which the eyes may have been damaged secondary to the dryness[2].

- A mouth examination may be performed to determine if signs of mouth dryness are present. These signs may include, sticky oral mucosa, tooth decay, and cavities in certain locations, thick saliva, and redness inside the oral cavity. The physician may also be able to note inflamed or under-producing salivary glands during this examination[2].

- A lip biopsy is a method used to determine if the dry mouth experienced by the patient is a symptom of Sjogren's syndrome. During this test, minor salivary glands are removed from the bottom lip and placed under a microscope. If the glands contain a certain arrangement of white blood cells, the test is positive for the salivary component of Sjogren's syndrome[2].

Because dry eyes and dry mouth are common symptoms and side effects of a number of diseases and treatments, including radiation to the head and neck, the physician will commonly perform a battery of additional tests to confirm no other causes. These tests may include:

- Blood tests may be performed to determine the presence of antibodies and immunological substances often found in individuals positive for Sjogren's. Antibodies commonly present in affected individuals include immunoglobulins, antithyroid antibodies, rheumatoid factors, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), and Sjogren's antibodies.

- Chest X-Rays are a method used to examine for inflammation of the lungs, which may be present in Sjogren's syndrome.

- A urine analysis may also take place to determine if the kidneys are functioning properly[2].

Between 1989 and 1996, the classification criteria for Sjögren’s syndrome (SS) were established by the European Study Group on Classification for Sjogren's syndrome[6]. These criteria and rules for diagnosing SS were then revised in 2002 by the American-European Consensus Group. Many of these criteria for classification involve the tests explained above. The below tables display the classification criteria for Sjogren's syndrome as proposed by the American-European Consensus Group:

| Revised international classification criteria for Sjogren’s syndrome[6] |

| I. Ocular symptoms: a positive response to at least one of the following questions: 1. Have you had daily, persistent, troublesome dry eyes for more than 3 months? 2. Do you have a recurrent sensation of sand or gravel in the eyes? 3. Do you use tear substitutes more than 3 times a day? |

| II. Oral symptoms: a positive response to at least one of the following questions: 1. Have you had a daily feeling of dry mouth for more than 3 months? 2. Have you had recurrently or persistently swollen salivary glands as an adult? 3. Do you frequently drink liquids to aid in swallowing dry food? |

| III. Ocular signs—objective evidence of ocular involvement defined as a positive result for at least one of the following two tests: 1. Schirmer's test, performed without anesthesia (less than or equal to 5 mm in 5 minutes) 2. Rose bengal score or other ocular dye score (greater than 4 according to the van Bijsterveld's scoring system) |

| IV. Histopathology: In minor salivary glands (obtained through normal-appearing mucosa) focal lymphocytic sialoadenitis, evaluated by an expert histopathologist, with a focus score greater than or equal to 1, defined as a number of lymphocytic foci (which are adjacent to normal-appearing mucous acini and contain more than 50 lymphocytes) per 4 mm2 of glandular tissue. |

| V. Salivary gland involvement: objective evidence of salivary gland involvement defined by a positive result for at least one of the following diagnostic tests: 1. Unstimulated whole salivary flow (<1.5 ml in 15 minutes) 2. Parotid sialography showing the presence of diffuse sialectasias (punctate, cavitary or destructive pattern), without evidence of obstruction in the major ducts19 3. Salivary scintigraphy showing delayed uptake, reduced concentration and/or delayed excretion of tracer20 |

| VI. Autoantibodies: presence in the serum of the following autoantibodies: 1. Antibodies to Ro(SSA) or La(SSB) antigens, or both |

(The above table was adapted from Table 2 in Vitali C, et al. Classification criteria for Sjogren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:554-558. See references below.)

| Revised rules for classification[6] |

| For primary SS In patients without any potentially associated disease, primary SS may be defined as follows: a. The presence of any 4 of the 6 items is indicative of primary SS, as long as either item IV (Histopathology) or VI (Serology) is positive b. The presence of any 3 of the 4 objective criteria items (that is, items III, IV, V, VI) c. The classification tree procedure represents a valid alternative method for classification, although it should be more properly used in clinical-epidemiological survey |

| For secondary SS In patients with a potentially associated disease (for instance, another well defined connective tissue disease), the presence of item I or item II plus any 2 from among items III, IV, and V may be considered as indicative of secondary SS |

| Exclusion Criteria: Past head and neck radiation treatment Hepatitis C infection Acquired immunodeficiency disease (AIDS) Pre-existing lymphoma Sarcoidosis Graft versus host disease Use of anticholinergic drugs (since a time shorter than 4-fold the half-life of the drug) |

(The above table was adapted from Table 3 in Vitali C, et al. Classification criteria for Sjogren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:554-558. See references below.)

Etiology/Causes [edit | edit source]

The primary symptoms of Sjogren's syndrome, including the dry eyes and dry mouth, are a result of the destruction of the exocrine (lacrimal and salivary) glands by focal T-lymphocytic infiltrates[3]. T-cells and B-cells are components of the immune system and usually work together to destroy foreign structures in the body, such as viruses and bacterias. However, in autoimmune diseases, such as Sjogren's syndrome, these cells interfere with the function and structure of organs within the body. In the case of Sjogren's, these cells interfere with glandular function[3].

Regulation of the salivary glands by the nervous system is impaired, and the secretory acinar apparatus displays structural abnormalities[3]. The acinus is the terminal end of the exocrine gland where the secretions are produced. The membrane of this structure lacks the laminin alpha-1 chain, which may explain this organ's inability to induce differentiation of the stem cells into acinar cells[3].

Evidence in the pattern of cases suggests that the cause of Sjogren's syndrome has a genetic component[3]. Recent research has found that the same gene variant commonly present in individuals with other connective tissue diseases, such as RA and lupus is also associated with Sjogren's syndrome[2]. The discovery of the STAT4 gene variant in association with autoimmune diseases could lead to a number of cutting edge treatments[2], including the possibility of gene replacement therapy to combat these incurable conditions.

As with other autoimmune diseases, scientists believe that Sjogren's may be triggered by an infection in individuals with a genetic predisposition[2]. This infection jump-starts the immune system. However, instead of calming down when the infection is eradicated, the immune system continues to remain on high alert and starts to destroy the body's own cells.

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Individuals with Sjogren's syndrome are prone to a number of problems such as inflammation and infection throughout the body. These issues may include[3][2]:

Pulmonary Problems

- Bronchitis

- Tracheobronchitis

- Lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis

- Pleurisy

Kidney Problems

- Interstitial nephritis

- Glomerulonephritis (rarely)

- Renal tubular acidosis

- Hypokalemia

Nervous System Problems

- Peripheral neuropathy

- Cranial neuropathy

Liver Problems

- Hepatitis

- Cirrhosis

Thyroid Problems

- Grave's disease

- Hashimoto's thyroiditis

Vascular Problems:

- Vasculitis

- Raynaud's phenomenon

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Common medical practice revolves around medication to treat Sjogren's syndrome. Specifically, physicians aim to control the dry eyes using substitute topical agents and manage extra-glandular symptoms with glucocorticoids and immunosuppressive drugs[7]. Many of these pharmaceutical therapies can be seen in the Medications section of this page.

Current evidence does support frequently using preservative-free tear substitutes to treat dry eyes during the day and using the ocular lubricating ointment at night[7]. The ointments are not suggested for day time use secondary to the application producing blurred and cloudy vision. The treatment recommended to a patient may depend upon the severity of the patient's symptoms. To treat moderate to severe dry eyes associated with Sjogren's syndrome, controlled trials support the application of topical 0.05% cyclosporine two times a day[7]. Topical NSAIDs or glucocorticosteroids may be required for the patients suffering from severe refractory ocular dryness[7]. In extreme cases of severely dry eyes, a patient may elect to undergo a punctual occlusion. This is a surgical procedure that attempts to keep the natural tears over the surface of the eye by closing the tear ducts that drain said tears from the eye[2].

For patients experiencing mild to moderate dry mouth, studies support the use of saliva replacement products and/ or sugar-free gum[7]. Along with the use of such products, it is suggested that individuals practice thorough oral hygiene whilst avoiding smoking and alcohol consumption[7][2]. Oral pilocarpine and cevimeline are the preferred treatments for patients who have maintained residual salivary gland function, however, these two drugs have not yet been tested in a comparison study to determine which is more effective[7]. Recommended daily doses are as follows:

- Pilocarpine: 5 mg every 6 hours

- Cevimeline: 30 mg every 8 hours

If a patient presents with contraindications for these therapies or is not tolerant of these medications, it has been found that N-acetylcysteine is an acceptable alternative[7].

The studies supporting the use of glucocorticoids and immunosuppressants have been small providing limited evidence for the prescription of such therapies. However, Rituximab has been shown to improve some extra-glandular symptoms, including vasculitis, neuropathy, glomerulonephritis, and arthritis[7].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Individuals with Sjogren's syndrome have reduced physical capacity and tend to fatigue very easily. While research on the effects of exercise on individuals diagnosed with Sjogren's is limited, the available studies suggest these patients benefit from moderate to high-intensity levels of exercise[3]. This type of activity has a positive influence on aerobic capacity, fatigue, physical function, and mood.

Further research is required to understand the effects exercise may have on individuals with varying severities of this disease, and to determine the long-term effects exercise may have on their symptoms[3]. However, some of the musculoskeletal presentations of SS are muscle and joint pain, along with arthritis. Thererfore, a patient may be treated by a physical therapist to relieve these symptoms[8].

Lifestyle Changes[edit | edit source]

There are also several things a patient can do at home in order to manage his or her symptoms. These may include[2]:

- Over the counter eye drops

- Chewing gum or sucking on hard candy to increase oral secretions

- Drinking water to relieve a dry mouth

- Using lip balm to moisten the lips

- Practice thorough oral hygiene to avoid oral infection

- Heavy moisturizing creams or ointment for dry skin

- Humidifier to hydrate the skin and moisten the air for breathing

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

There are several diseases that present with symptoms similar to Sjogren's syndrome, including the dry eyes and dry mouth3. Some differential diagnoses include:

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Vasculitis

- Thyroid disease

- Scleroderma

- Medication side-effects

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

Szturmowicz M, Wilinska E, Paczek A, et al. Primary Sjogren's syndrome with two extraglandular sites involvement-case report. Pneumonol. Alergol. Pol. 2010:78;445-450.

Ahmada Y, Shahrila N, Husseina H, Said M. Case review of sarcoidosis resembling Sjogren's syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine Research 2010:2;284-288.

Moutasim K, Shirlaw P, Escudier M, Poate T. Congenital heart block associated with Sjogren syndrome: case report. Internal Archives of Medicine 2009:2;21.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Disease

- American College of Rheumatology

- Sjogren's Syndrome Foundation

- National Eye Institute

- American Academy of Ophthalmology

- American Autoimmune-Related Diseases Associated, Inc. (AARDA)

- Arthritis Foundation

- National Organization for Rare Disorders (NORD)

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 American College of Rheumatology. Sjogren's Syndrome. http://www.rheumatology.org/practice/clinical/patients/diseases_and_conditions/sjogrens.asp (accessed 17 March 2011).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 2.25 2.26 2.27 2.28 2.29 National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Sjogren's Syndrome. http://ww.niams.niih.gov/Health_Info/Sjogrens_Syndrome/default.asp (accessed 17 March 2011).

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 Goodman C, Fuller K. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. Denver, CO: Saunders, 2009.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Szturmowicz M, Wilinska E, Paczek A, Wawrzynska L, Opoka L, Gatarek J, Langfort R, Rowinska-Zakrzewska E, Torbicki A. Primary Sjogren's syndrome with two extraglandular sites involvement- case report. Pneumonol. Alergol. Pol. 2010;78:445-450. https://docs.google.com/viewer?url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.pneumonologia.viamedica.pl%2Fdarmowy_pdf.phtml%3Findeks%3D55%26indeks_art%3D644 (accessed 17 March 2011)

- ↑ PubMed Health. Drugs and Supplements. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/s/drugs_and_supplements/a/ (accessed 6 April 2011).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Vitali C, Bombardieri S, Jonsson R, Moutsopoulos H, Alexander E, Carsons S, Daniels T, Fox P, Fox R, Kassan S, Pilemer S, Tala N, Weisman M, and the European Study Group on Classification Criteria for Sjogren's Syndrome. Classification criteria for Sjogren's syndrome: a revised version of the European criteria proposed by the American-European Consensus Group. Ann Rheum Dis 2002;61:554-558. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1754137/pdf/v061p00554.pdf (accessed 6 April 2011)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 7.8 Ramos-Casals M, Tzioufas A, Stone J, Siso A, Bosch X. Treatment of primary sjogren syndrome: a systemic review. JAMA 2010;304:452-460. http://jama.ama-assn.org/content/304/4/452.long (accessed 17 March 2011).

- ↑ Medline Plus. Sjogren Syndrome. http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000456.htm (accessed 6 April 2011)