Shoulder Subluxation

Original Editor Bart Moreels

Top Contributors - Wendy Walker, Lucinda hampton, Bart Moreels, Khloud Shreif, Admin, Jana Beckers, Simisola Ajeyalemi, WikiSysop, Fasuba Ayobami, Kim Jackson, Amanda Ager, Scott Buxton, Naomi O'Reilly, Joao Costa and Wanda van Niekerk

Definition[edit | edit source]

Glenohumeral subluxation is defined as a partial or incomplete dislocation that usually stems from changes in the mechanical integrity of the joint. In a subluxation, the humeral head slips out of the glenoid cavity as a result of weakness in the rotator cuff or a blow to the shoulder area. A subluxation can occur in one of three types: anterior (forward), posterior (backward), and inferior (downward). The difference with a shoulder dislocation is the fact that the humeral head pops back into its socket.

Clinically relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

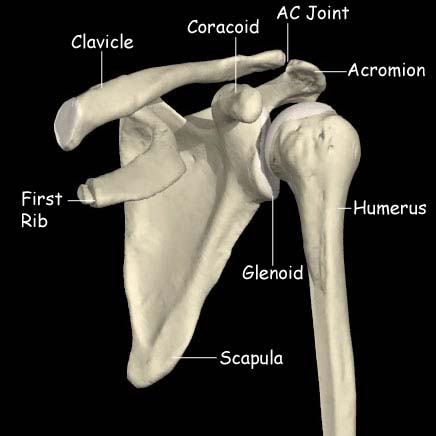

The shoulder joint (or glenohumeral joint) permits the greatest range of motion of any joint. Because it is also the most frequently dislocated joint, it provides an excellent demonstration of the principle that stability must be sacrificed to obtain mobility. It consists of 3 bone structures: humerus, scapula and clavicle. These bones make a total of 3 synovial joints: gleno-humeral , sterno-clavicular and acromio-clavicular joint. Besides these you also find the subacromial “joint” and the scapular-thoracal “joint”. The size of the glenoid cavity is increased by a fibrous cartilaginous glenoid labrum, which continues beyond the bony rim and deepens the socket. The bones of the pectoral girdle provide some stability to the superior surface, because the acromion and coracoid process project laterally superior to the head of the humerus. But most of the stability is provided by the surrounding skeletal muscles, with help from their associated tendons and various ligaments. The major ligaments that help stabilise the shoulder joint are the glenohumeral, coracohumeral, coracoacromial and the acromiohumeral ligaments. The acromioclavicular ligament reinforces the capsule of the acromioclavicular joint and supports the superior surface of the shoulder. The largest ligament is the Glenohumeral ligament, and this is commonly damaged or overstretched in shoulder joint subluxation. [1]. The muscles that move the humerus stabilise the shoulder more than all the ligaments and capsular fibres combined. Muscles originating on the trunk, pectoral girdle and humerus cover the anterior, superior and posterior surfaces of the capsule. The tendons of the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, teres minor and subscapularis reinforce the joint capsule and limit the range of motion. These muscles, known as the rotator cuff, are the primary mechanism for supporting the shoulder joint and limiting its ROM.

Video[edit | edit source]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Studies show that there is no relationship between shoulder pain, shoulder subluxation and gender. It equally occurs within men and women.

Shoulder subluxations frequently occur in people with hemiplegic stroke or with a paralysed upper limb. The reported incidence varies greatly, from 17% to 81% [2] [3]

Traumatic subluxations of the shoulder can occur in many sports, including football, rugby, wrestling and boxing.

Characteristics/clinical presentation[edit | edit source]

The main problem with shoulder subluxation is the instability of the gleno-humeral joint. The anatomy of this joint permits a large range of movement, but it sacrifices stability. Research by Basmajian determined that the musculus supraspinatus and in minor ways also the posterior fibres of the deltoid muscle play a key role in maintaining glenohumeralalignment. Chaco and Wolf, did confirm this in their study, which said that the supra spinatus is very important in preventing the downward subluxation of the humerus. Subluxation occurs with the shoulder in abduction and externally rotation.Other research shows that the most important ligamental structure to maintain correct shoulder position and also to prevent shoulder subluxation is the inferior glenohumeral ligament.This ligament is most important during external rotation and abduction during the cocking face of the throwing motion.

Shoulder subluxation can lead to soft tissue damage as traction damage can occur due to gravitational pull forces and poor protection is offered by a weak shoulder. It is usually quite painful, and there might be a partial numbness of the shoulder, arm and hand.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Acromioclaviculair joint injury[edit | edit source]

Acromioclavicular (AC) joint injuries are common and often seen after bicycle wrecks, contact sports, and car accidents. The acromioclavicular joint is located at the top of the shoulder where the acromion process and the clavicle meet to form a joint. Several ligaments surround this joint, and depending on the severity of the injury, a person may tear one or all of the ligaments. Torn ligaments lead to

acromioclavicular joint sprains and separations.[4]

Biceps tendinopathy[edit | edit source]

Bicep tendinopathy, is an inflammatory process of the long head of the biceps tendon and is a common cause of shoulder pain due to its position and function.

Clavicular injuries[edit | edit source]

Although clavicle fractures are common and usually heal regardless of the selected treatment, complications are possible, warranting careful attention to these injuries. Multiple attempts have been made to devise a classification scheme for clavicle fractures. The most common system is the following one, created by Allman, in which the clavicle injuries is divided into thirds:

• Group I fractures: Middle third injuries

• Group II fractures: Distal third injuries

• Group III fractures: Medial (proximal) third injuries

Rotator cuff injury[edit | edit source]

Rotator cuff injuries are a common cause of shoulder pain in people of all age groups. They represent a spectrum of disease, ranging from acute reversible tendinitis to massive tears involving the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and subscapularis. Diagnosis is usually made through detailed history, physical examination, and often, imaging studies.

Shoulder dislocation[edit | edit source]

Shoulder dislocations may occur from a traumatic injury or from loose capsular ligaments. Different conditions may affect the stabilising structures of the shoulder and, thus, negatively affect patients with shoulder dislocations.

Swimmer’s shoulder[edit | edit source]

Swimmer's shoulder is the term used to describe the problem of shoulder pain in the competitive swimmer. Swimming is an unusual sport in that the shoulders and upper extremities are used for locomotion, while at the same time requiring above average shoulder flexibility and range of motion (ROM) for maximal efficiency. This is often associated with an undesirable increase in joint laxity.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Symptoms:

Patients with shoulder subluxations commonly present with:

- Pain in the shoulder region

- Loss of range of movement

- Palpable gap between acromion and humeral head (this can be informally measure in finger-widths)

Functional testing:

The subluxation test is positive = resistance is given, when patient brings arm in throwing stance, in internal rotation direction.

Pain in the ventral capsule indicates a frontal capsule lesion.

Pressure during resistance test on the dorsal part of the humerus can provoke ventral gliding. The result is sudden pain in the shoulder and in a number of cases there is a subluxation to the front. This test can be conducted in different degrees of abduction and with or without the support of the upper arm.

Radiographic measurements are considered to be the most accurate way of evaluating the degree of subluxation[5]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Oxford Instability Shoulder Score (OISS)

The OISS is a 12-item questionnaire with five possible Likert style responses for each question and has a range from 0 to 48 (with a score of 48 indicating better shoulder function). The OISS has been developed and validated for shoulder instability and has also undergone testing to assess responsiveness in shoulder instability patients.

Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI)

The WOSI score is a 21-item questionnaire with a 100-mm horizontal visual analogue scale under each question for patient responses and ranges from 0 to 2100 and is converted to a percentage, with 100% representing the highest possible shoulder-related quality of life. The WOSI is a rigorously designed and evaluated measurement tool for patients with shoulder instability and has been shown to have excel- lent responsiveness in posterior instability.

Examination[edit | edit source]

First the examinor should ask the patient about the history of the reason he subluxated his arm. Than he can perform an inspection, when he does he should make sure that he can have a visual on both shoulders at the same time to see the different.

After this you could use different tests to test whether the patient had a subluxation of the shoulder:

- Load and shift test

In this test the examiner stabilises the scapula and moves the humeral head to posterior and anterior. With this test the examiner can feel if the humeral head is going to subluxate.

- Push-Pull test

The patients arm is placed in 90 degrees of adduction and 30 degrees of forward flexion. With his other hand the examiner grasps the midhumerus and provides posteriorly directed force. This test is used to measure the posterior laxity of the shoulder.

- Protzman test

This test is similar to the Load and shift test but the second hand is placed in the axilla to feel for translation of the humeral head or to feel if the humeral head subluxates over the rim.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

In the hemiplegic patient[edit | edit source]

Sling/support:[edit | edit source]

Traditionally supportive devices, in the form of slings or braces, have been used to manage shoulder subluxation following CVA; the aim being to support the weight of the arm thus preventing/minimising the inferior pull on the humerus and reducing the stretch on the joint capsule. A Cochrane Review [6] in 2009 concluded that there is insufficient evidence to conclude whether supportive devices are of benefit.

Electrical Stimulation:[edit | edit source]

In a Cochrane Review [7] Functional Electrical Stimulation was found to bring about improvement in pain-free range of passive humeral lateral rotation and to reduce the severity of glenohumeral subluxation; however there was no significant effect on upper limb motor recovery.

Advice/Management:[edit | edit source]

- Teach patient/carers/relatives how to position the limb so that the weight of the arm is supported [8]

- Judicious passive or active assisted exercises should be started within 24 hours poststroke with the aim of maintaining range of movement of the shoulder joint[9]

In the non-hemplegic patient[edit | edit source]

-Prevention of reccurance:

Strengthening exercises to re-establish the strength of the rotator cuff muscles is recommended.

Initial physical therapy interventions may include:

- Mobility exercises including PROM, AAROM, AROM

- Motor control training

- Scapular stabilization

- Isometric and low-grade strengthening exercises

- Manual therapy directed at the Glenohumeral, Acromio-Clavicular and Sterno-

Clavicular joint

- Manual therapy of cervicothoracic spine and upper ribs

- Activity modification

Late stages of rehabilitation of rotator cuff injury include progressive resistive strengthening, proprioception and sport-specific exercises.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Aras MD, Gokkaya NK, Comert D, Kaya A, et al. (2004). Shoulder pain in hemiplegia: results from a national rehabilitation hospital in Turkey. American Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 83(9):713-9.

- ↑ Huang SW, Liu SY, Tang HW, Wei TS, Wang WT, Yang CP. Relationship between severity of shoulder subluxation and soft-tissue injury in hemiplegic stroke patients. J Rehabil Med. 2012 Sep;44(9):733-9.

- ↑ Hartwig M, Gelbrich G, Griewing B. Functional orthosis in shoulder joint subluxation after ischaemic brain stroke to avoid post-hemiplegic shoulder-hand syndrome: a randomized clinical trial. Clin Rehabil. 2012 Sep;26(9):807-16.

- ↑ https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/92337-overview#showall

- ↑ Paci M, Nannetti L, Rinaldi LA. Glenohumeral subluxation in hemiplegia: An overview. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2005 Jul-Aug;42(4):557-68.

- ↑ Ada L, Foongchomcheay A, Canning C. Supportive devices for preventing and treating subluxation of the shoulder after stroke. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005 Jan 25;(1):CD003863.

- ↑ Price CI, Pandyan AD Electrical stimulation for preventing and treating post-stroke shoulder pain: a systematic Cochrane review Clinical Rehabilitation. Clin Rehabil. 2001;15:5-19.

- ↑ Kaplan MC. Hemiplegic shoulder pain-early prevention and rehabilitation. West J Med. Feb 1995;162(2):151-2

- ↑ Kumar R, Metter EJ, Mehta AJ, Chew T. Shoulder pain in hemiplegia. The role of exercise. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. Aug 1990;69(4):205-8