Shoulder Instability

Original Editor - Johanna Guim and Katherine Burdeaux as part of the Temple University Evidence-Based Practice Project

Lead Editors

Definition

[edit | edit source]

The term ‘shoulder instability’ is used to refer to the inability to maintain the humeral head in the glenoid fossa.[1]The ligamentous and muscle structures around the glenohumeral joint, under non-pathological conditions, create a balanced net joint reaction force. The relevant structures are listed below. If the integrity of any of these structures is disrupted it can lead to atraumatic or traumatic instability. Atraumatic instability commonly results from repetitive overhead movements or congenital joint features. Traumatic mechanisms of injury may result in frank dislocations where there is a loss of joint integrity. Instability can occur anteriorly, posteriorly, or in multiple directions regardless of mechanism of injury.

Common Categorizations of Shoulder Instability

■ Two groups:

■Traumatic

■ Atraumatic

● 2 types of atraumatic instabilities

○ Chronic Recurrent Instabilities

■ May be seen after surgery for shoulder dislocation, due to glenoid rim lesions.[2]

■ Over time, microtrauma can lead to instability of the glenohumeral joint.

○ Congenital Instabilities

■ Laxity of structures in the shoulder which may be present since birth.[3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy

[edit | edit source]

Many anatomic structures may lead to shoulder instability. These structures may include one or a combination of the following:

■ Static Stabilizers[4]

○ Superior Glenohumeral Ligament (SGHL)

● Limits anterior and inferior translation

of adducted humerus

○ Medial Gleonohumeral Ligament (MGHL)

● Limits anterior translation in lower and middle range of abduction

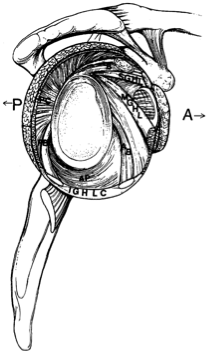

○ Inferior Glenohumeral Ligament (IGHL)

● Longest glenohumeral ligament

● Primary static restraint against anterior and posterior and inferior translation when humerus is abducted beyond 45 degrees

○ Glenoid Labrum

● Increases depth of glenoid cavity. Increases stability up to 50%[3]

○ Negative intra-articular pressure[4]

● Assists in maximizing joint congruency.

■ Dynamic Stabilizers[3]: Assist with holding the humeral head in the glenoid fossa during movement

○ Primary

● Rotator Cuff Muscles (Supraspinatis, Infraspinatis, Teres Minor, Subscapularis)

● Deltoid

● Long Head of Biceps

○ Secondary

● Teres Major

● Latissimus Dorsi

● Pectoralis Major

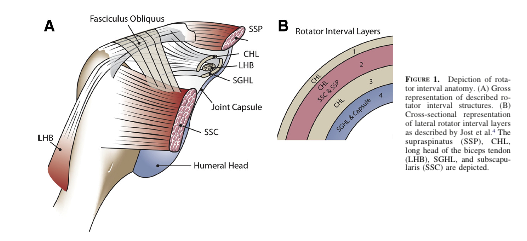

■ Rotator Cuff Interval: This interval is a triangular-shaped area found in the shoulder, with borders noted below. A large rotator interval allows for increased anterior humeral head translation due the lack of structures supporting the joint capsule anteriorly.[3]

○ Superior Border

● Anterior margin of supraspinatus

○ Inferior Border

● Subscapularis

○ Apex

● Transverse Humeral Ligament

○ Base

● Coracoid Process

| Anterior | Posterior | Multidirectional |

| SGHL,MGHL, Anterior IGHL | SGHL, Posterior IGHL | Dysfunction of Dynamic Stabilizers |

| Anterior Capsule | Posterior Capsule | Joint Capsule in 2 or more directions. Inferior capsule is primarily affected |

| Coracohumeral Ligament | Coracohumeral Ligament | All Structures involved in Anterior or Posterior instability can be affected |

| Superior Anterior Labrum | ||

| Long Head of Biceps | ||

| Subscapularis |

Epidemiology [edit | edit source]

98% of primary dislocations occur anteriorly.[4] The rate of recurrence is most common in younger populations (see figure 1B3). The incidence of congenital instability is unknown.[3]

Mechanism of Injury/ Pathological Process

[edit | edit source]

○ Most common glenohumeral dislocations occur in two directions and results in loss of joint integrity.

■ Anterior

● Sports, falls particularly when upper extremity is in 90° abduction and external rotation

■ Posterior

● Seizures, shock, falls

■ Atraumatic

○ Two types: congenital or chronic recurrent

■ Chronic Recurrent

○ Caused by repetitive extreme external rotation with the humerus abducted and extended (i.e.- pitching motion).[3] Instability may be caused by gradual weakening of the anterior and inferior static restraints. The humeral head will tend to move away from shortened structures. For example: posterior shoulder capsular tightness will cause the humeral head to shift anteriorly, resulting in a loss of integrity of all anterior structures.

○ Common concomitant features or causes:

● Bankart lesion

● HillSachs lesion

● SLAP lesion (Superior Labrum Anterior Posterior)

● HAGL lesion (Humeral Avulsion of Glenohumeral Ligaments)

● ALPSA lesion (Ant. Labroligamentous Periosteal Sleeve Avulsion)

● Laxity of the joint capsule

○ Commonly associated with participation in sports such as gymnastics, baseball, softball, tennis, swimming, and weight training.[3]

■ Congenital Instability[3]

○ Hypoplastic glenoid

○ Decrease anterior-posterior diameter of glenoid

○ Increased retroversion of glenoid

○ Increased amount and composition of collagen and elastin

○ Bony anomalies

Clinical Presentation [edit | edit source]

Possible signs and symptoms of chronic/recurrent instability

■ Anterior instability

○ Clicking/pain

○ Complain of dead arm with throwing

○ Pain posteriorly

○ Possible subacromial or internal impingement signs

○ The patient may have a positive apprehension test, relocation test, and/or anterior release test

○ Increased joint accessory motion particularly in the anterior direction

■ Posterior instability

○ Possible subacromial or internal impingement

○ Glenohumeral internal rotation deficit (GIRD) may be present

○ Pain/clicking

○ Increased joint accessory motion particularly in the posterior direction

■ Multidirectional instability

○ Antero-inferior laxity most commonly presents with global shoulder pain, cannot pin point to a specific location

○ May have a positive sulcus sign, apprehension/relocation test, anterior release tests

○ Secondary rotator cuff impingement can be seen with microtraumatic events caused during participation in sports such as gymnastics, swimming and weight training[3]

○ Increased joint accessory motion in multiple planes

Differential Diagnosis [edit | edit source]

■ Rotator Cuff Tear

■ Subacromial Impingement

■ Internal Impingement

■ Cervical Spine Mechanical Pain (referring to shoulder)

■ Biceps Tendinopathy

■ Labral Pathology

■ Laxity due to congenital causes (ie: Ehlers-Danlos Syndrome)

Examination [edit | edit source]

■ Subjective history:

○ May have history of trauma with or without a previous dislocation

○ May have history of lax joints (consider elbow, knee, thumb hyperextension[3]; use Beighton scale to evaluate hypermobility)

○ activities of daily living may be difficult to complete

○ global pain around shoulder[3]

■ Physical examination

○ Screen cervical spine and thoracic spine

○ Observation/Palpation: long head of biceps, supraspinatus tendon, AC joint, SC joint, spine, 1st rib, other regional muscles

○ Posture[5]: asymmetry, scapular winging, atrophy

○ Active ROM: look for apprehensive behavior; glenohumeral flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, external rotation, internal rotation, scaption; elbow flexion and extension

○ Passive ROM: may have pain, stiffness

○ Muscle length testing: upper trapezius, levator scapulae, scalenes, latissimus dorsi, lower trapezius, pectoralis minor, pectoralis major

○ Resistive testing

○ Functional testing[6]: hand to posterior neck; hand to scapula; hand to opposite scapula

○ Joint accessory motion testing: increased mobility in direction of instability (anterior, posterior, multidirectional)

○ Scapular/thoracic motion[3]

○ Proprioception

○ Special tests: possibly sulcus sign, apprehension/relocation and/or anterior release tests depending on suspected form of instability

Diagnostic Procedures/ Special tests[edit | edit source]

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | + LR | -LR |

| Sulcus |

0.17 |

0.93 | 2.43 | 0.89 |

|

Anterior Release Test[7] |

0.92 | 0.89 | 8.36 | 0.09 |

| Apprehension[8] | 0.53 | 0.99 | 53 | 0.47 |

| Relocation[8] | 0.46 | 0.54 | 1 | 1 |

→ provocative tests used for detecting shoulder instability:

→ laxity examinations

Laxity examinations

- Application: The patient lies on his back with the scapula on the table but the caput free. Load the caput humerus into the glenoid and then translate the caput in the anterior and posterior directions.

- Conclusion: The test aims to evaluate the amount of translation of the caput humerus on the glenoid. There are many methodes to grade the test but the most common one is the Hawkins grading. This method is considered to be the best one because it has a clinical basis. Hawkins divided the movement in four grades: Grade 0 = little to no movement; grade 1 = the humeral head rises up onto the glenoid rim; grade 2 = when the caput humerus can be dislocate but relocate spontaneously; grade 3 = when the head does not relocate after the pressure.

- Clinical bottom line: Tzannes and Murell[9] have concluded that this test is entirely reliable (p<0,0001) and a LR > 80 for instability.

Drawer test:

- Application: The patient is positioned supine. The examiner holds the patients scapula with his left hand while grasping the patient’s upper arm and drawing the humeral anterior head with his right hand. You can hold the shoulder in a different position.

- Conclusion: The test tells you more about the laxity. The test is positive when the thumb was felt to slide past the coracoid.

- Clinical bottom line: Tzannes and Murell[10] have concluded that this test is still to be assessed as to its validity and reliability.

- Application: The patient’s elbow is pulled inferiorly while the patient is relaxed

- Conclusion: This manoeuvre tests the superior glenohumeral ligament. The test is positive when there is a sulcus of more than 2 cm between the acromion and caput humerus.

- Clinical bottom line: Tzannes and Murell[11] also evaluate this test as being completely reliable (p<0,0001). Nakagawa et al report a specificity of 0.93.

Provocative tests [edit | edit source]

Anterior release test/ Surprise Test:

- Application: In this test, the examiner applies posteriorly directed force to the humeral head, with the patient being in abduction and external rotation.

- Conclusion: The test is positive in case of pain or apprehension when easing the pressure.

- Clinical bottom line: In the light of the results of Tzannes and Murell[12](p<0,0001) and Ian et al[13] we can conclude that it is a reliable test for the detection of the unstable shoulder. Gross et al report a sensitivity of 0.92 and a specificity of 0.89, making this test useful to rule out shoulder instability with a negative result.

Apprehension/augmentation test:

- Application: The apprehension test is being applied when the patient is lying or sitting with the shoulder in a neutral position (90° abduction). The examiner holds the patient’s wrist with one hand and with the other hand he applies anteriorly directed force to the humeral head.

- Conclusion: Signs of glenohumeral anterior instability are: pain, a feeling of subluxation or clear defence. If a relocation test is being applied almost immediately after the apprehension test and if this relocation test results to be negative, than we can decide that there is anterior instability.

- Clinical bottom line: Based on the results of Levy et al.[14]; Ian et al.[15](sensitivity = 53 & specificity = 99), Tzannes and Murell[16] (p= 0,0004 pain and/or apprehension and a LR 8-100 for anterior instability) and Marx et al.[17], we are able to conclude that there is not sufficient clinical proof to detect or exclude instability. Lo et al report a specificity of 0.99.

- Application: The patient is in the starting position of the apprehension test and the examiner now applies posteriorly directed force to the humeral head.

- Conclusion: When this test results to be negative, there is glenohumeral anterior instability.

- Clinical bottom line: The article by Ian et al. [18] (sensitivity = 45 & specificity = 54) states that the relocation test is not clinically evident. However, other articles by Tzannes and Murell[19] (p= 0,0003 pain and/or apprehension) and Liu et al.[20] provide evidence to the contrary. Lo et al report poor psychometric properties on this test.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

Disabilities of Shoulder, Arm, and Hand (DASH)

quick DASH

Visual Analogue Scale

Diagnosis Specific Questionnaires[21]

■ Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index

■ Oxford Shoulder Instability Questionnaire

■ Melbourne Instability Shoulder Scale

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Medical management will hinge on the specifics of the patient presentation including the mechanism of injury, severity, patient goals, etc. In some cases, particularly those with a traumatic mechanism, surgical intervention may be warranted to restore joint stability.

Types of Surgical Procedures for Traumatic Glenohumeral Dislocations[3]

■Open capsular shift

■Arthroscopic thermal capsulorraphy

Physical Therapy Management [edit | edit source]

Non-operative physical therapy management will vary in a case-by-case situation and each patient’s care should be individualized to target their specific goals. Physical therapy management is largely impairment-based and response-driven as there is little high level evidence to assist decision making.

PT commonly includes:

○Education to prevent recurrence

○ Postural re-education

○ Motor control training

■ Of specific muscles during functional activities (rotator cuff muscles, scapular stabilizers)

○ Strengthening

■ Particularly deltoid, rotator cuff musculs and scapular stabilizers.

○ Stretching

■ Particularly of posterior shoulder structures, pectoralis major and minor

■ Any other muscles with flexibility impairments

○ Manual therapy:

■ Targeting any impairments in mobility of the GH, AC, SC joint and cervico-thoracic spine[22]

Post-Op PT Management:

■ Depends on

o surgical procedure/surgeon’s protocol

o mechanism of injury

o concomitant injuries

o tissue quality

o impairments noted at evaluation

Clinical Bottom Line

[edit | edit source]

● Shoulder instability may have a traumatic or atraumatic cause.

● The recurrence rate after primary shoulder dislocation is greatest in individuals <20 years old.

● Rehab should be based on each patient’s case with consideration to the surgeon’s preference.

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://eutils.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1t1: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

References will automatically be added here, see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Tzannes A, Murrel, GAC. An assessment of the interexaminar reliability of tests for shoulder instability. The journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2004; 13:18-23.

- ↑ Charousset C, Beauthler V, Bellaïche, Guillin R, Brassart N, Thomazeau H. Can we improve radiological analysis of osseous lesions in chronic anterior shoulder instability? Orthop. Traumatol. Surg. Res. 2010;96:88-93.

- ↑ 3.00 3.01 3.02 3.03 3.04 3.05 3.06 3.07 3.08 3.09 3.10 3.11 3.12 Guerrero P, Busconi B, Deangelis N, Powers G. Congenital instability of the shoulder joint: assessment and treatment options. JOSPT. 2009;39(2):124-134.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Hayes K, Callanan M, Walton J. Shoulder instability: Management and rehabilitation. JOSPT 2002;23(10):497-509.

- ↑ Jaggi A. Rehabilitation for shoulder instability. Br J Sports Med 2010;44(5):333.

- ↑ Yang J, Lin J. Reliability of function-related tests in patients with shoulder pathologies. JOSPT. 2006;36: 572-576.

- ↑ Gross M, Disefano M. Anterior release test: A new test for occult shoulder instability. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 1997;339:105-108.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lo IK, Nonweiler B, Woolfrey M, Litchfield R, Kirkley A. An evaluation of the apprehension, relocation, and surprise tests for anterior shoulder instability. Am J Sports Med.2004;32:301-7

- ↑ Tzannes A, Murrel, GAC. An assessment of the interexaminar reliability of tests for shoulder instability. The journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2004; 13:18-23.

- ↑ Tzannes A, Murell GAC. Clinical examination of the unstable shoulder. Sports Medicine 2002; 32: 447-457.

- ↑ Tzannes et al. 2004

- ↑ Tzannes et al. 2002

- ↑ Ian KY, Lo IKY, Nonweiler B, et al. An evaluation of the apprehension, relocation, and surprise test for anterior shoulder instability. American Journal of Sports Medicine 2004; 32:301-307.

- ↑ Levy AS, Lintner S, Kenter K, et al: intra- and interobserver reproducibility of the shoulder laxity examination. The American Journal of Sports medicine 1999; 4: 460-463.

- ↑ Ian et al.

- ↑ Tzannes A, Murrel, GAC. An assessment of the interexaminar reliability of tests for shoulder instability. The journal of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery 2004; 13:18-23.

- ↑ Marx RG, Bombardier C, Wright JG. What do we know about the reliability and validity of physical examination tests used to examine the upper extremity? Journal of Hand Surgery 1999; 24A:185-193.

- ↑ Ian et al.

- ↑ Tzannes et al. 2004

- ↑ Liu SH, Henry MH, Nuccion S, et al. Diagnosis of glenoid labral tears. A comparison between magnetic resonance imaging and clinical examinations. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 1996; 2:149-154.

- ↑ Rouleau D, Faber K, MacDermin J. Systematic review of patient-administered shoulder functional scores on instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19:1121-1128.

- ↑ Mintken. Some Factors Predict Successful Short-Term Outcomes in IndividualsWith Shoulder Pain Receiving Cervicothoracic Manipulation: A Single-Arm Trial. PTJ 2010;26-42.