Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome

Original Editors - Karsten De Koster

Top Contributors - Karsten De Koster, Claudia Karina, Nick Van Doorsselaer, Alex Palmer, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Kenza Mostaqim, Arno Van Hemelryck, Luna Antonis, Kim Jackson, Bieke Bardyn, Sally Ngo, WikiSysop, Wanda van Niekerk, Naomi O'Reilly, Fitz Van Roy, 127.0.0.1, Claire Knott, Venus Pagare, Chelsea Mclene, Daniele Barilla and Kai A. Sigel

Search Strategy[edit | edit source]

Databases: VUBis, Pedro, Google scholar, Pubmed, Orthobullets, Runnersworld

Search words: “Shin Splints”, “Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome”, “Tibial Stress Syndrome”, “MTSS”, “Posteromedial Tibial Stress Syndrome”, “Anterior Tibial Stress Syndrome”, “Anterolateral Tibial Stress Syndrome”, “Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome”, “CECS”

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

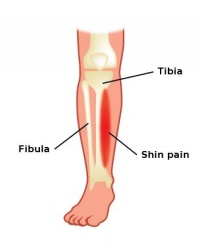

The American Medical Association defines shin-splint syndrome as “Pain and discomfort in the lower leg. It is caused by repetitive loading stress during running and jumping, and occurs in 4% to 35% of athletic and military populations. [1]The diagnosis should be limited to musculoskeletal inflammation, excluding stress fractures or ischemic disorders.”

Shin-splints is a general term for overuse injuries of the lower leg, and it induced pain along the posteriormedial border of the (distal third) of the tibia over a length of at least 5 cm. [2] [3]

A synonym for shin-splints is medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS), But Bruckner and Kahn say: “A more descriptive term that accounts for the inflammatory, traction event on the tibial aspect of the leg common in runners is medial tibial traction periostitis or just medial tibial periostitis”.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

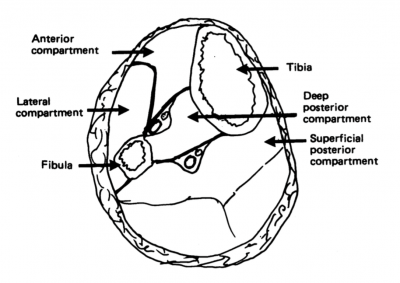

The pathophysiology of shin splints is more easily understood after examining the relevant cross-sectional anatomy. There are 4 muscle compartments in the leg:

- A) Anterior: this compartiment contains the tibialis anterior muscle, the extensor hallucis longus, the extensor digitorum longus and the peroneus tertius. The tibialis anterior dorsiflexes the ankle and inverts the foot. The extensor hallucis longus extends the great toe, the extensor digitorum longus extends the other toes and assists in eversion as does the peroneus tertius.

- B) Deep posterior: this contains the flexor digitorum longus, the tibialis posterior and the flexor hallucis longus. The tibialis posterior plantar flexes and inverts the foot. The others are predominantly toe flexors.

- C) Superficial posterior: this is the gastrocnemius and soleus group; predominatly plantar flexors of the ankle.

- D) Lateral: this compartment contains the peroneus brevis and longus, mainly foot evertors (see figure 3).[4]

A dysfunction of tibialis anterior and posterior are commonly implicated, also the area of attachment of these muscles can be the location of pain. [5] Muscle imbalance and inflexibility, especially tightness of the triceps surae (gastrocnemius, soleus, and plantaris muscles), is commonly associated with MTSS . Athletes with muscle weakness of the triceps surae are more prone to muscle fatigue, leading to altered running mechanics, and strain on the tibia. Clinicians should also examine for inflexibility and imbalance of the hamstring and quadriceps muscles. [6]

Figure1:

Chasan N., shin-splints, http://srcpt.blogspot.com/2009/02/shin-splints.html, 2 February 2009

anatomy lower leg

Epidemiology /Etiology

[edit | edit source]

Shin-splints is most common with running and jumping athletes who made training errors, especially when they overload or when they run too fast for their potential. This injury can also be related to changes in the training program, such as an increase in distance, intensity and duration.[9] Running on a hard or uneven surface and bad running shoes (like a poor shock absorbing capacity) could be one of the factors related to the casualty. Biomechanical abnormalities as foot arch abnormalities, hyperpronation of the foot, unequal leg length,..[10] are the most frequently mentioned intrinsic factors.

Women have an increased risk to incur stress fractures, especially with this syndrome. This is due to nutrional, hormonal and biomechanical abnormalities. Individuals who are overweight are more susceptible to getting this syndrome. Therefore it is important that people who are overweight, combine their exercise with a diet or try to lose weight before starting therapy or a training program. These people, along with poor conditioned individuals, should always slowly increase their training level. Cold weather contributes to this symptom, therefore it’s important (even more than usual) to warm up properly. [11]

Internally a chronic inflammation of the muscular attachment along the posterior medial tibia and bony changes are considered to be the most likely cause of the medial tibial stress syndrome.[12]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The main symptom is dull pain located along the second third of the length of the posteromedial tibia. A mild oedema in this painful area may also be present. The symptoms are often bilateral[13]. The pain is caused by repeated loanding and take-off from a hard or uneven surface [14]. This pain worsens at each moment of contact.[15] At first the patient only feels pain at the beginning of the workout, often disappearing while exercising, only to return during the cool-down period. When shin splints get worse the pain can remain during exercise.

The most common complication of shin-splints is a stress fracture, which shows itself by tenderness of the anterior tibia.[16]

Neurovascular signs and symptoms are not commonly attributable to MTSS and when present, other pathologies such as chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS) or vascular deficiencies should be considered as the source of leg pain.

Bone scanning shows diffuse uptake in the affected region of the tibia. [17][18] [19]

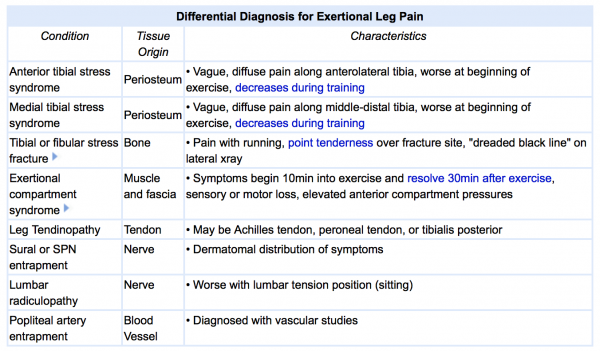

Differential Diagnosis [20][edit | edit source]

- Stress Fracture

- Chronic Exertional Compartmental Syndrome

- Sciatica

- Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

- Popliteal Artery Entrapment

- Muscle Strain

- Tumour

- Arterial endofibrosis

- Infection

- Nerve entrapment (common/superficial peroneus and saphenous)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The following are two conditions that are sometimes mistakenly diagnosed as shin splints.

Pain on the anterior (outside) part of the lower leg may be compartment syndrome—a swelling of muscles within a closed compartment—which creates pressure. The symptoms of compartment syndrome include leg pain, unusual nerve sensations, and eventually muscle weakness.

Pain in the lower leg could also be a stress fracture (an incomplete crack in the bone), which is a far more serious injury than shin splints. The pain of shin splints is also more generalized than that of a stress fracture. Press your fingertips along your shin, and if you can find a definite spot of sharp pain, it's a sign of a stress fracture. Additionally, stress fractures often feel better in the morning because the bone has rested all night; shin splints often feel worse in the morning because the soft tissue tightens overnight. Shin splints are also at their most painful when you forcibly try to lift your foot up at the ankle and flex your foot. [22]

Imaging studies are not necessary to diagnose shin-splints, but when a conservative treatment fails, it could be useful to undertake an echo. If the injury has evolved into a stress fracture, an x-ray scan can show black lines. A triple-phase bone scan can show the difference between a stress fracture and a medial tibial stress syndrome.[7] The MRI can also exclude tumors/edemas.[23]

Detmer in 1986 developed a classification system to subdivide MTSS into three types: (i) type I - tibial microfracture, bone stress reaction or cortical fracture; (ii) type II - periostalgia from chronic avulsion of the periosteum at the perios teal-fascial junction; and (iii) type ill – chronic compartment syndrome.

In the recent literature. stress fracture and compartment syndrome arc qualified as separate entities. [24]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The MTSS score is a valid, reliable and responsive PROM to measure the severity of MTSS. It is designed to evaluate treatment outcomes in clinical studies.

Winters M, Moen MH, Zimmermann WO, Lindeboom R, Weir A, Backx FJ, Bakker

EW.Br J. The medial tibial stress syndrome score: a new patient-reported outcome

measure. Sports Med. 2015. pii: bjsports-2015-095060. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095060.

Examination[edit | edit source]

For the physical examination a good palpation of the lower leg will be necessary. The medial ridge of the tibia (origin of the tibialis posterior and soleus muscles) is often tender to palpation, especially at the distal and middle tibial regions. The anterior tibia, however, is usually nontender. Neurovascular symptoms are usually absent.

Physicians should carefully evaluate for possible knee abnormalities (especially genu varus or valgus), tibial torsion, femoral anteversion, foot arch abnormalities, or a leg-length discrepancy. Ankle movements and subtalar motion should also be evaluated. Clinicians should also examine for inflexibility and imbalance of the hamstring and quadriceps muscles and weakness of “core muscles”. Core and pelvic muscle stability may be assessed by evaluating patient’s ability to maintain a controlled, level pelvis during a pelvic bridge from the supine position, or a standing single-leg knee bend.

Examining patient’s shoes may reveal generally worn-out shoes or patterns consistent with a leg-length discrepancy or other biomechanical abnormalities.

Abnormal gait patterns should be evaluated with the patient walking and running on a treadmill. [26][27][28][29][30][31] [32][33][34][35][36][37][38]

Pelvic bridge exercise to strengthen gluteal core muscles. Courtesy: R. Michael Galbraith

Pelvic bridge exercise to strengthen gluteal core muscles. Courtesy: R. Michael Galbraith

Medical Management

[edit | edit source]

Surgical treatment is rarely needed. It is indicated in the athlete who has failed one year's conservative treatment or in whom the condition is recurrent (two or more times). A posterior fasciotomy is the common procedure performed. It consists of one or more fascial incisions to relieve tension or pressure commonly to treat the resulting loss of circulation. They are often not a complete resolution but may improve symptoms of pain and function. Postoperatively patients must follow a graded rehabilitation program similar to that used in non-operative treatment. [39][40][41]

Other treatment options include ultrasound, extracorporeal shockwave therapy, and steroid injections. Schulze et al looked at various treatment options from application of local and systemic anti-inflammatory medicaments to physiotherapy with ultrasound, phonophoresis, and local friction. However, they concluded none of these methods has proven to be superior to the others. [42]

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Shin-splints can be treated conservatively or surgically. Essentially the treatment may focus on: (a) reducing stress; (b) relieving pain; (c) providing alternative programs to maintain fitness; (d) correcting specific etiologic factors and (e) reintegration of the athlete into activity.[11] We will start with a conservative treatment:

Acute phase:

The conservative treatment of this injury starts with rest. A therapist will recommend you 2-6 weeks of rest. This rest should be strictly applied. Otherwise the symptoms can be worsened. Prolonged rest is not ideal for an athlete, thus other therapies are necessary for a quick and safe return after a period of rest. This rest can be assisted by medication. NSAIDs and Acetaminophen are often used for analgesia. The second thing a therapist will say is to use ice and eventually analgesic gels. The cryotherapy can be used after exercise for a period of 20 minutes. There are a number of physical therapy modalities to use in the acute phase but there is no proof that these therapies such as ultrasound, soft tissue mobilization, electrical stimulation,..[43] would be effective.[9] A corticoid injection is contraindicated because this can give a worse sense of health. Because the healthy tissue is also treated. A corticoid injection is given to reduce the pain, but only in connection with rest.[10]

For the treatment of shin-splints it’s important to screen the risk factors, this makes it easier to make a diagnosis and to prevent this disease. In the next table you can find them[44]:

| Intrinsic factors | Extrinsic factors |

| Age Sex Height Weight Body fat Femoral neck anteversion Genu valgus Pes clavus Hyperpronation Joint laxity Aerobic endurance/conditioning Fatigue Strength of and balance between flexors and extensors Flexibility of muscles/joints Sporting skill/coordination Physiological factors |

Sports-related factors Type of sport Exposure (e.g., running on one side of the road) Nature of event (e.g., running on hills) Equipment Shoe/surface interface Venue/supervision Playing surface Safety measures Weather conditions Temperature |

Subacute phase:

The treatment should aim to modify training conditions and to address eventual biomechanical abnormalities. Change of training conditions could be decreased running distance, intensity and frequency and intensity by 50%. It is advised to avoid hills and uneven surfaces.

During the rehabilitation period the patient can do low impact and cross-training exercises (like running on a hydro-gym machine).). After a few weeks athletes may slowly increase training intensity and duration and add sport-specific activities, and hill running to their rehabilitation program as long as they remain pain-free.

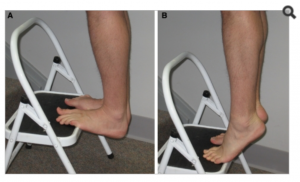

A stretching and strengthening (eccentric) calf exercise program can be introduced to prevent muscle fatigue. [45][46][47]

Eccentric calf stretches and strengthening exercises. Courtesy: R. Michael Galbraith

Eccentric calf stretches and strengthening exercises. Courtesy: R. Michael Galbraith

Patients may also benefit from strengthening core hip muscles. Developing core stability with strong abdominal, gluteal, and hip muscles can improve running mechanics and prevent lower-extremity overuse injuries. [48]

Proprioceptive balance training is crucial in neuromuscular education. This can be done with a one-legged stand or balance board. Improved proprioception will increase the efficiency of joint and postural-stabilizing muscles and help the body react to running surface incongruities, also key in preventing re-injury. [49]

Another thing that can help prevent a new or re-injury is to choose good shoes with good shock absorption. Therefore it is important to change your shoes every 250-500 miles, a distance at which most shoes lose up to 40% of their shock-absorbing capabilities.

In case of biomechanical problems of the foot may individuals benefit from orthotics. An over-the-counter orthosis (flexible or semi-rigid) can help with excessive foot pronation and pes planus. A cast or a pneumatic brace can be necessary in severe cases.[50]

Manual therapy can be used to control several biomechanical abnormalities of the spine, sacro-illiacal joint and various muscle imbalances. They are often used to prevent relapsing to the old injury. But manual therapy is not the only therapy that can be used; there is also acupuncture, ultrasound therapy injections and extracorporeal shock-wave therapy but heir efficiency is not yet proved.

The vast majority of individuals with MTSS have significant improvement, if not complete resolution, of their symptoms with conservative management. Surgery is usually reserved for recalcitrant cases who do not respond with conservative treatment. They are often not a complete resolution but may improve symptoms of pain and function.[51]

Case Studies[edit | edit source]

- Diagnosis and management of acute medial tibial stress syndrome in a 15 year old female surf life-saving competitor

- Medial tibial stress syndrome: A skeleton from medieval Rhodes demonstrates the appearance of the bone surface – a case report

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Primary resources:

GALBRAITH R.M. and LAVALEE M.E., ‘Medial Tibial Stress syndrome: conservative treatment options’, Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med.; September 2009, 2(3):127-133. (E)

Craig D.I., ‘Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Evidence-based Prevention’, J Athl Training, June 2008; 43(3): 316-318. (A)

THACKER S.B.,(2002) ‘The prevention of shin splints in sports: a systematic review of literature’ , Medicine & science in sports & exercises, the first of November 2002; 34(1):32-40. (A)

PURANEN J. and ORAVA S., (1979) ‘ Athletes’ leg pain’, British Journal of Sports Medcine, Spetmber 1979; 13(3):p.92-97. (C)

Secondary resources:

Broos P., Sportletsels, Leuven/Apeldoorn: Garant, 1991. (p.22, 179-181).

Kjær M. et al, Sports Medicine; Basic science and clinical aspects of sports injury and physical activity, Oxford: Blackwell Publishing,2003. (p.530-535).

Peterson L. and Renström Per, Sports injuries: their prevention and treatment, 3th edition, London: Dunitz, 2001. (p.11,339-342).

Reid D.C. et al., Sports injury assessment and rehabilitation, New York/ London/ Melbourne/ Tokyo: Churchill Livingstone,1992. (p.269-280).

BECK B., (1998) ‘Tibial stress injuries: an aetiological review for the purposes of guiding management’, Sports Medicine, 1998, 26(4) 265-279.

BRUCKNER P. and KHAN K., ‘Clinical sports medicine’, 3th edition,North Ryde: McGraw-Hill, 2007(p.555-575).

Chasan N., shin-splints, (http://srcpt.blogspot.com/2009/02/shin-splints.html), 2 February 2009.

Sportsinjuryclininc, shin splints, (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jg79mQqiacM), online video, last accessed, 13 October 2007.

Widmark E., How to indentify, treat and prevent medial tibial stress syndrome, (http://www.fysionutrition.se/wp-content/uploads/How-to-treat-and-prevent-medial-tibial-stress-syndrome.pdf), 2009.

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

‘Shin splints’ is a vague term that implicates pain and discomfort in the lower leg, caused by repetitive loading stress. There can be all sorts of causes to this pathology according to different researches. Therefore, a good knowledge of the anatomy is always important, but it’s also important you know the other disorders of the lower leg to rule out other possibilities, which makes it easier to understand what’s going wrong. Also a detailed screening of known’s risk factors, intrinsic as well as extrinsic, to recognize factors that could add to the cause of the condition and address these problems.[52]

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

• Sobhani V, Shakibaee A, Khatibi Aghda A, Emami Meybodi MK, Delavari A, Jahandideh D.Asian J. Studying the Relation Between Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome and Anatomic and Anthropometric Characteristics of Military Male Personnel. Sports Med. 2015 Jun;6(2):e23811. Doi: 10.5812/asjsm.23811. Epub 2015 Jun 20.

• Department of Podiatry, Hackensack University Medical Center, Hackensack, NJ, USA. Electronic address: [email protected]. Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2016 Apr;33(2):219-33. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2015.12.002. Epub 2016 Feb 3.

• Franklyn M, Oakes B.World J Orthop. Aetiology and mechanisms of injury in medial tibial stress syndrome: Current and future developments. 2015 Sep 18;6(8):577-89. doi:10.5312/wjo.v6.i8.577. eCollection 2015 Sep 18.

References

[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Yates, Ben, and Shaun White. The incidence and risk factors in the development of medial tibial stress syndrome among naval recruits. The American journal of sports medicine. 2004; 32.3: 772-780. (Level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ Kudo, Shintarou, and Yasuhiko Hatanaka. Forefoot flexibility and medial tibial stress syndrome. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery. 2015; 23.3: 357. (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ http://www.physio-pedia.com/Leg_and_Foot_Stress_Fractures . (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Batt, Mark E. "Shin Splints-A Review of Terminology." Clinical journal of sport medicine 5.1 (1995): 53-57. (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Thacker SB, Gilchrist J, Stroup DF, Kimsey CD (2002). 'The prevention of shin splints in sports: a systematic review of literature'. Medicine & Science

- ↑ Galbraith RM, Lavalee ME (2009). 'Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Conservative Treatment Options', Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(3), pp. 127-133

- ↑ October 14, 2015/ Christye Estes, http://blog.voltathletics.com/home/2015/10/14/body-talk-with-christye-shin-splints-and-how-to-fix-em

- ↑ Batt, Mark E. "Shin Splints-A Review of Terminology." Clinical journal of sport medicine 5.1 (1995): 53-57.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Galbraith RM, Lavalee ME (2009). 'Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Conservative Treatment Options', Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(3), pp. 127-133.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Broos P (1991). Sportletsels : aan het locomotorisch apparaat. Leuven: Garant, pp. 179-181.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedReid, 1992 - ↑ Peterson L, Renström P (2001). Sports Injuries: Their Prevention and Treatment. London: Dunitz, pp. 339-342.

- ↑ Reid DC (1992). Sports Injury Assessment and Rehabilitation, New York: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ Peterson L, Renström P (2001). Sports Injuries: Their Prevention and Treatment. London: Dunitz, pp. 339-342.

- ↑ Broos P (1991). Sportletsels : aan het locomotorisch apparaat. Leuven: Garant, pp. 179-181.

- ↑ Galbraith RM, Lavalee ME (2009). 'Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Conservative Treatment Options', Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(3), pp. 127-133.

- ↑ Wilder R, Seth S. Overuse injuries: tendinopathies, stress fractures, compartment syndrome, and shin splints. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23(1):55-81. (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ 16. Kortebein PM, Kaufman KR, Basford JR, Stuart MJ. Medial tibial stress syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32(3 Suppl):S27-33.(Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Antonios G Angoules. Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome in Athletes: Diagnostic and НerapeutLc Approach. Journal of Novel Physiotherapies. 2015;5(2).(Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics. Shin Splints / Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome. Available at: http://www.wheelessonline.com/orth/shin_splints_medial_tibial_stress_syndromefckLR[Accessed 24th Aug 2008].

- ↑ http://www.orthobullets.com/sports/3108/tibial-stress-syndrome-shin-splints . (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ http://www.runnersworld.com/tag/shin-splints . (Level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Broos P (1991). Sportletsels : aan het locomotorisch apparaat. Leuven: Garant, pp. 179-181.

- ↑ Moen, Maarten H., et al. Medial tibial stress syndrome. Sports medicine. 2009; 39(7): 523-546. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Physiotutors. Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome / MTSS / Shin Splints. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KrCpFoR5PCY

- ↑ Beck B (1998). 'Tibial stress injuries: an aetiological review for the purposes of guiding management', Sports Medicine, 26(4), pp. 265-279.

- ↑ Kortebein PM, Kaufman KR, Basford JR, Stuart MJ. Medial tibial stress syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32(3 Suppl):S27-33.(Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Wilder R, Seth S. Overuse injuries: tendinopathies, stress fractures, compartment syndrome, and shin splints. Clin Sports Med. 2004;23(1):55-81. (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ Moen, Maarten H., et al. Medial tibial stress syndrome. Sports medicine. 2009; 39(7): 523-546. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Fredericson M. Common injuries in runners. Diagnosis, rehabilitation and prevention. Sports Med. 1996;21:49–72. (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ Galbraith RM, Lavalee ME (2009). 'Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Conservative Treatment Options', Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(3), pp. 127-133.

- ↑ Strakowski J, Jamil T. Management of common running injuries. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2006;17(3):537–552.(Level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ Dugan S, Weber K. Stress fracture and rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18(3):401–416. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Sommer H, Vallentyne S. Effect of foot posture on the incidence of medial tibial stress syndrome. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1995;27:800–804. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Niemuth P, Johnson R, Myers M, Thieman T. Hip muscle weakness and overuse injuries in recreational runners. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(1):14–21. (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Greenman P. Principles of manual medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2003;3(11):337–403, 489. . (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Howell J. Effect of counterstrain on stretch reflexes, Hoffmann reflexes, and clinical outcomes in subjects with plantar fasciitis. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2006;106(9):547–556. (Level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Karageanes S. Principles of manual sports medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins. 2005: 467–468. Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Yates B, Allen MJ, Barnes MR. Outcome of surgical treatment of medial tibial stress syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(10):1974-80. (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ Yates B, Allen MJ, Barnes MR. Outcome of surgical treatment of medial tibial stress syndrome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A(10):1974-80. (Level of evidence 4)

- ↑ Holen KJ, Engebretsen L, Grontvedt T, Rossvoll I, Hammer S, Stoltz V. Surgical treatment of medial tibial stress syndrome (shin splint) by fasciotomy of the superficial posterior compartment of the leg. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1995;5(1):40-3. (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Moen M, Holtslag L, Bakker E, et al. The treatment of medial tibialfckLR stress syndrome in athletes; a randomized clinical trial. BMC SportsfckLR Science 2012;4:12 . (Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Beck B (1998). 'Tibial stress injuries: an aetiological review for the purposes of guiding management', Sports Medicine, 26(4), pp. 265-279.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedThacker, 2002 - ↑ Dugan S, Weber K. Stress fracture and rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2007;18(3):401–416. (Level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Couture C, Karlson K. Tibial stress injuries: decisive diagnosis and treatment of ‘shin splints’. Phys Sportsmed. 2002;30(6):29–36.(Level of evidence 3)

- ↑ DeLee J, Drez D, Miller M. DeLee and Drez’s orthopaedic sports medicine principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. 2003:2155–2159.(Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ DeLee J, Drez D, Miller M. DeLee and Drez’s orthopaedic sports medicine principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. 2003:2155–2159.(Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ DeLee J, Drez D, Miller M. DeLee and Drez’s orthopaedic sports medicine principles and practice. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders. 2003:2155–2159.(Level of evidence 1A)

- ↑ Galbraith RM, Lavalee ME (2009). 'Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Conservative Treatment Options', Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(3), pp. 127-133.

- ↑ Galbraith RM, Lavalee ME (2009). 'Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome: Conservative Treatment Options', Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 2(3), pp. 127-133.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedp6

8. Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics. Shin Splints / Medial Tibial Stress Syndrome. Available at: http://www.wheelessonline.com/orth/shin_splints_medial_tibial_stress_syndromefckLR[Accessed 24th Aug 2008].