Sepsis

Original Editors - Leana Louw

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Leana Louw, Rachael Lowe, Kim Jackson, Admin, Aminat Abolade, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka and Carina Therese Magtibay

Description[edit | edit source]

Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is an exaggerated defense response of the body to a noxious stressor ( eg.infection, trauma, surgery, acute inflammation, ischemia or reperfusion, malignancy) to localize and then eliminate the endogenous or exogenous source of the insult (see Immune system)

- It involves the release of acute-phase reactants which are direct mediators of widespread autonomic, endocrine, hematological and immunological alteration in the subject.

- Even though the purpose is defensive, the dysregulated cytokine storm has the potential to cause massive inflammatory cascade leading to reversible or irreversible end-organ dysfunction and even death.

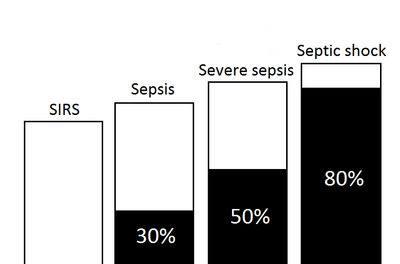

The graph R shows the mortality assosiacted with sepsis

- SIRS with a suspected source of infection is termed sepsis.

- Sepsis with one or more end-organ failure is called severe sepsis

- Sepsis with hemodynamic instability in spite of intravascular volume repletion is called septic shock. This can potentially lead to multiorgan failure where the body is unable to maintain haemostasis without medical intervention, a common cause of death in the ICU setting.[1]

Together they represent a physiologic continuum with progressively worsening balance between pro and anti-inflammatory responses of the body[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

The incidence of sepsis is set at 50-95 per 100 000 with an suspected increase of 9% per year. This is further made up by:[3]

- 2% of hospital admissions

- 9% of sepsis results in severe sepsis

- 3% septic shock

- 10% of ICU admissions per year

- Peak age around 60's

Etiology[edit | edit source]

The 2009 European Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC II study) determined that gram-negative bacterial infections far exceed other etiologies as the most common cause of sepsis syndromes with a frequency of 62%, followed by gram-positive infections at 47%.

- An increase in the prevalence of the latter may be attributable to the performance of more invasive procedures and increased incidence of nosocomial infections.

- Predominant micro-organisms isolated in patients include Staphylococcus aureus (20%), Pseudomonas (20%), and Escherichia coli (16%). Predominant sites of infection include respiratory (42%), bloodstream (21%), and genitourinary (10%).

- The influence of bacterial strain and site of infection on mortality was illustrated in a large meta-analysis. In this study, gram-negative infections were overall associated with higher mortality.

Sepsis syndromes caused by multidrug-resistant bacterial strains (methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus, vancomycin-resistant enterococci ) are on the rise with a current incidence of up to 25%; viruses and parasites cause far fewer cases and are identified in 2% to 4% of cases[4]

Risk factors:

- Diabetes

- Malignancy

- Chronic kidney and liver disease

- Use of corticosteroids

- Immunosuppressed state

- Burns

- Major surgery

- Trauma

- Presence of indwelling catheters

- Prolonged hospitalization

- Hemodialysis

- Extremes of age[4]

80% of sepsis cases is the result of the following infections:[3]

- Chest (e.g. pneumonia)

- Abdomen

- Genitourinary system

- Primary bloodstream

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Pathogens have the ability to trigger intercellular events in a variety of cells, including the neuroendocrine system, immune cells, epithelium and endothelium. Proinflammatory mediators attempt to eradicate the pathogens, a process that is controlled by anti-inflammatory mediators. This inflammatory process leads to tissue damage, changes in the leukocytes resulting in immune changes. When this natural control process fails, it leads to systemic inflammation and the infection is converted to sepsis or septic shock.[3]

The hypothalamic thermostat is reset by the fever caused by sepsis. In an attempt to cool down, it results in peripheral vasodilatoation and subsequent depletion of the visceral perfusion. Excess nitric oxide production is stimulated by endotoxins and this leads to uncontrolled vasodilatation and a “functional haemorrhage”. Increased cardiac output is thus unsuccessful at maintaining an adequate blood pressure. This can lead to hypoxic tissue damage.[3]

Shock in general normally runs the following course:[3]

Insufficient tissue perfusion → anaerobic metabolism → lactic acidosis → metabolic acidosis → cellular damage → organ failure.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Criteria[1]

Two or more of the following:

- High grade (> 38˚C) or low grade (< 36˚C ) fevers

- Heart rate > 90/minute

- RR > 20/minute OR PaCO2 < 4.3kPa

- WCC > 12

Signs and symptoms[3]

- Pyrexia

- Flushed presentation

- Tachypnea

- Hypotension

- Bounding pulse

- Restricted regional blood flow as the result of vasopressors

- Signs of tissue hypoperfusion:

- Areas of mottled skin

- Oliguria

- Mental confusion

- Delayed capillary refill

- Hyperlactacidaemia

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Septic shock can only be diagnosed when it fits to the clinical criteria and a infection (and the pathogen if possible) is verified.[3]

- Identification of infection:

- Look for obvious signs - e.g. community-aquired pneumonia, prupura fulminans, cellulitis, wound discharge.

- Blood tests / tissue biopsy or sample to determine pathogen

- Bloods:

- PCR

- Microarray based rapid

- Assess for issue hypoperfusion

- Glasgow coma scale to determine mental confusion (unable to do in sedated patients)

- Input and output measures to determine oliguria

- Multi-organ failure

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- SOFA (sepsis-related organ failure assessment) score

- qSOFA (quick sepsis-related organ failure assessment)

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Below guidelines are derived from the Surviving Sepsis Campaign Guidelines

- Source Control

- Broad-spectrum antibiotics within one hour of diagnosis for all patients. Initial empiric anti-infective therapy should have activity against all likely pathogens and adequate penetration of source tissue.

- Removal of infected/necrotic tissue, if it is the source of septic shock, i.e. patients with cellulitis, abscess, infected devices, purulent wounds.

2. Management of Shock

- Measures most effective if achieved within the first six hours of diagnosis

- Restore central venous pressure (CVP) to 8 mmHg to 12 mmHg

- Restore mean arterial pressure (MAP) greater than 65 mmHg

- Restore superior vena cava saturation to 70% or mixed venous saturation to 65%

- Fluid resuscitation with crystalloid (NS or albumin) and colloid (blood products) up to 80 ml/kg

- Mechanical ventilation to reduce metabolic demand

- First-line vasoactive agents (epinephrine in cold shock versus norepinephrine in warm shock) when fluid-refractory Note: dopamine as a first-line agent has fallen out of favor.

3. Enhancing Host Response

- Corticosteroids indicated in vasoactive-refractory shock and or in patients with low (unstimulated) basal cortisol levels less than 150 ug/L)

- Addition of vasopressin indicated in vasoactive-refractory shock

Also of note

- The placement of an arterial line is important in the management of vasoactive-refractory shock for close monitoring of blood pressure and tissue oxygenation status via regular blood gasses with key attention to lactate levels and pO2.

- Patients with sepsis have high metabolism and thus prolonged starvation should be avoided. Early nutrition can help protect gut mucosa and prevent translocation of organisms from the GI tract into the systemic circulation[4].

Physiotherapy management[edit | edit source]

See the page for the role of physiotherapy in the ICU.

- Physiotherapy interventions in the ICU setting normally consists of respiratory physiotherapy focusing on airway clearance techniques and early mobilization. During acute sepsis or septic shock, patients are often too unstable for physiotherapy intervention, which only starts when the patient is haemodynamically stable.

- Positioning plays a big role in the management of patients with sepsis. A heads-up position of 30-45 degrees is recommended to decrease the risk of aspiration pneumonia and ventilator-associated pneumonia, where prone positioning is recommended in sepsis induced ARDS with a PF ratio of less than 150.[5]

- A common result of these are critical illness neuropathy, and extensive rehabilitation should then be incorporated in the ICU, after discharge to the ward, as well as in the out-patient setting with the aim of getting the patient back to his baseline level of function and participation as per the ICF model.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

Septic shock is a serious illness and despite all the advances in medicine, it still carries high mortality which can exceed 40%.

- Mortality does depend on many factors including the type of organism, antibiotic sensitivity, number of organs affected and patient age.

- The more factors that match SIRS, the higher the mortality.

- Data suggest that tachypnea and altered mental status are excellent predictors of poor outcome.

- Prolonged use of inotropes to maintain blood pressure is also associated with adverse outcomes.

- Those who survive are left with significant functional and cognitive deficits[4].

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Hough A. Physiotherapy in respiratory care: a problem-solving approach to respiratory and cardiac management. Springer; 2013.

- ↑ Chakraborty RK, Burns B. Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Sep 21. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.statpearls.com/kb/viewarticle/29832 (last accessed 22.9.2020)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Annane D, Bellissant E, Cavaillon JM. Septic shock. The Lancet 2005;365(9453):63-78.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Mahapatra S, Heffner AC. Septic Shock (Sepsis). InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Jun 4. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430939/ (last accessed 22.9.2020)

- ↑ Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, Kumar A, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B. Surviving sepsis campaign: international guidelines for management of sepsis and septic shock: 2016. Intensive care medicine 2017;43(3):304-77.