Salutogenic Approach to Wellness

Original Editor - Thalia Zamora Gómez

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton and Carin Hunter

Introduction[edit | edit source]

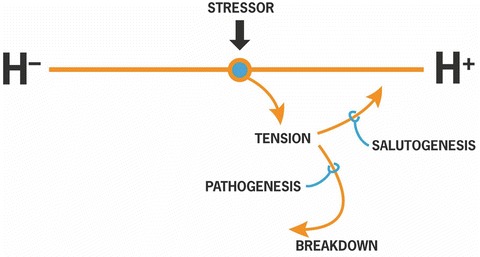

The salutogenic approach or salutogenesis is a term applied in health sciences, and more recently in other fields, to refer to an approach to wellness focusing on health and not on disease (pathogenesis). Literally, salutogenesis translates to “the origins of health”, from the Latin `Salus ́ meaning Health, and the Greek `Genesis ́ meaning origin or beginning. The term was first coined in 1979 by the medical sociologist Aaron Antonovsky in his book Health, Stress and Coping [1], after developing a theory that suggested that the way people view their life has a positive or negative influence on their health.

Back in 1971, Antonovsky had presented the results of an epidemiological study [2] in which he had interviewed a group of Israeli women who had been in concentration camps during the Holocaust, and despite all the terrible things they had been through, some of them had managed to stay in good health while others had not. Trying to find an explanation for these differences was the motivation for Antonovsky to develop the salutogenic theory.

In the beginning, Antonovsky’s research focus was on social class and health, but after a few years, his attention changed to the impact of stress on health.[3] During this time, throughout the late 1980s, the importance was on risk factors and disease; and stress was considered a high risk factor for breakdown. However, Antonovsky observed that change, chaos, stress and disease are a constant in life and therefore “natural” conditions of it; that human beings are in a heterostatic state rather than in homeostasis. All these observations raised the question of how we can survive with this disequilibrium. Over time, this consideration has given a more central role to the nature of the stress agent, as well as the ability of people to cope with it and the environment they are in. [4]Salutogenic Concepts[edit | edit source]

Aaron Antonovsky developed the salutogenic theory based on two concepts: the Sense of Coherence and the General Resistance Resources, and despite of having a mainly individualistic approach, both concepts can be applied at a societal level.[5]

Integrating concepts and main ideas from the Salutogenic Theory, a Health Promotion Movement focused on the respect of human rights began at the end of the 20th Century, which proposed people as active participating subjects. The principles of this health promotion were concentrated in the World Health Organisation Ottawa Charter [6], and at the center of the process, professionals and the general public were mutually engaged in an empowering process developing personal skills for strengthening communities and enabling people to live a good life.

Sense of Coherence[edit | edit source]

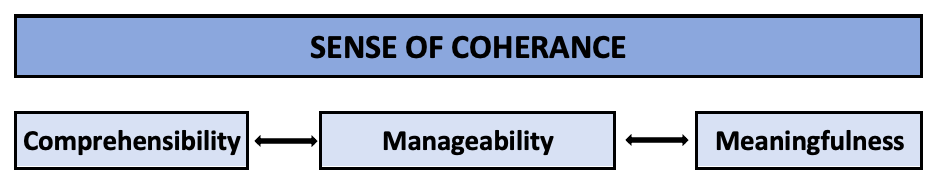

The Sense of Coherence can be explained as the ability to manage the resources one has in order to cope with the innumerable stressors of life, and a way of viewing or perceiving life as: [3]

Comprehensive[edit | edit source]

Cognitive Component; “The stimuli deriving from one’s internal and external environments in the course of living are structured, predictable and explicable”;

Manageable[edit | edit source]

Instrumental or Behavioural Component; “The resources are available to one to meet the demands posed by the stimuli”; and

Meaningful[edit | edit source]

Motivational Component; “These demands are challenges, worthy of investment and engagement”.In his 1987 book Unraveling the Mystery of Health. How People Manage Stress and Stay Well [3], Antonovsky developed the 29 Item Orientation to Life Questionnaire to measure the Sense of Coherence, including;

- 11 items to measure Comprehensibility,

- 10 items to measure manageability, and

- 8 items to measure meaningfulness.

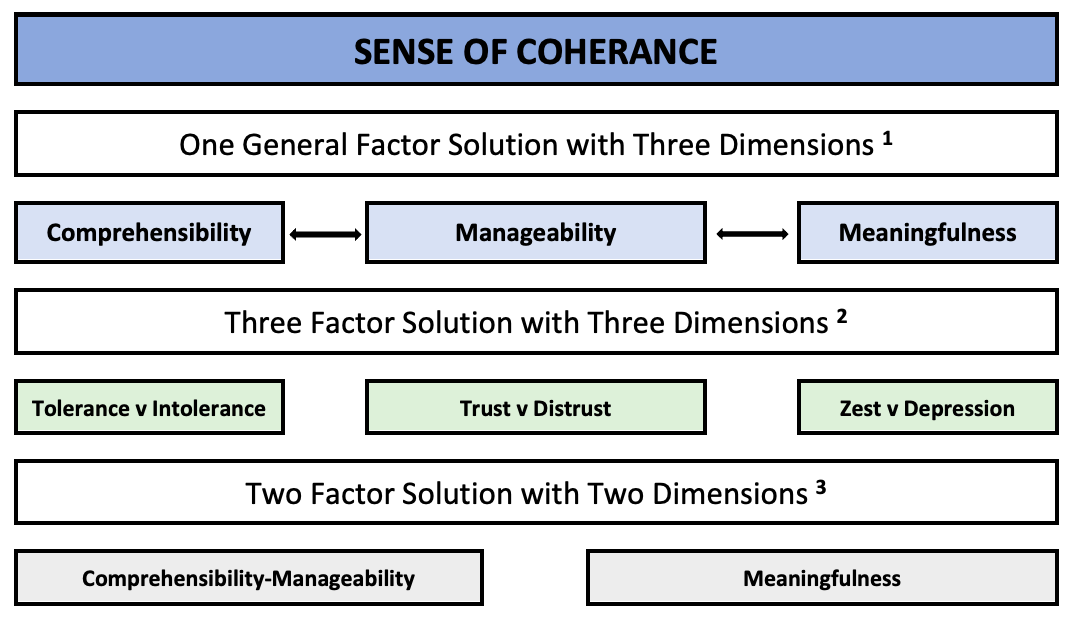

The response alternatives are on a scale of 1 to 7 points, and the accumulates score may range from 29 to 203. Another version of 13 questions was also developed by Antonovsky, and other scales have been created to measure the Sense of Coherence at community or family levels. Antonovsky’s Scales have been used in at least 49 languages and at least 48 different countries. The broad fields of application as well as recent research, have proved the Sense of Coherence to be a multidimensional construct, rather than unidimensional, as Antonovsky used to consider. [8]

General Resistance Resources[edit | edit source]

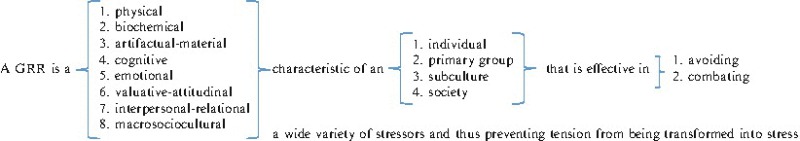

On the other hand “the General Resistance Resources are the biological, material and psychosocial factors that make it easier for people to perceive life as understandable, structured and consistent.” [10]

Some examples of General Resistance Resources include: [12]

- Money

- Knowledge and Intelligence

- Experience

- Self-Esteem

- Healthy Behaviour

- Social Support

- Ego / Identity

- Commitment and Cohesion with one’s Cultural Roots

- Cultural Stability

- Ritualistic Activities

- Religion and Philosophy (e.g., Stable set of answers to life’s perplexities)

- Genetic Factors

- Preventive Health Orientation

If a person has access to these kind of resources, there is a better chance for them to deal with the challenges of life and to construct coherent life experiences. “The general resistance resources lead to life experiences that promote a strong sense of coherence, the capability to perceive that one can manage in any situation independent of whatever is happening in life” [13]. General resistance resources would therefore, represent a type of health kit that could help individuals and their communities to improve or retain health. [10]

Salutogenic Interventions[edit | edit source]

In the same way, based on this theory, some authors [14] suggest that salutogenic strategies should be produced to;

- Facilitate communities to create shared life visions and to be part of decision making (meaningfulness);

- Develop shared mental models about the change process and desired outcomes (comprehensibility);

- Enable communities to identify life demands (e.g., stressors, challenges) and

- General resistance resources that need to be balanced (manageability) as well as life opportunities (e.g., assets, learning situations) that stimulate health development”. [10]

“Other authors have developed theoretical models to implement the salutogenic paradigm in different sectors, such as in schools [15], communities or neighbourhoods [16], health systems [17], or within different population groups such as children [18], people with chronic diseases” [10][19] , or migrants [20]. This last study of a 6 months’ health promotion program for migrant women at risk of social exclusion, evaluated the effectiveness of a salutogenic health promotion program focused on the empowerment of these women, with the acknowledgement of the health inequities that migrants experience based on variables like gender, country of origin or socioeconomic status. The objectives of the interventions in this case were addressed to improve self-knowledge, and to identify family and community roles (comprehensibility and manageability - sense of coherence) and personal capacities discussing future projects (manageability and meaningfulness - sense of coherence). Based on the increase i self-esteem and the physical quality of life, as well as on the reduction of perceived stress of migrant women, the authors suggest that the salutogenic model of health should be applied in health promotion programs and included in policies to reduce health inequity among migrant populations.[20]

The Salutogenic Model has applied many other strategies, like the ones revised by Álvarez et al [10], who identified 4 types of interventions:

- Individual Interventions; Focus on health education activities, counselling and/or psychotherapeutic methodologies from different approaches (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Psychodynamic, Occupational Therapy).” “These were developed, among others, in relation to physical morbidity (Human Immunodeficiency Virus, Mental Health and perceived Quality of Life and Health.

- Group Interventions; Developed in groups with similar health problems, include health education activities and different types of Psychotherapy (Cognitive Behavioral Therapy, Psychodynamic, Holistic, Community).” “These targeted different health topics, ranging from the management of chronic diseases, to mental health and subjective well-being, to social dimensions relating to social trust, social capital and social compromise.”

- Mixed Interventions; Incorporate combined actions at individual and group level.” “These mixed interventions present a wide range of topics linked to management of chronic pain, functional capacity improvement, Health-Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), drug consumption, and psychosomatic disorders.”

- Intersectoral Interventions; Carried out by collaborators from two or more different background areas (multidisciplinary teams) aiming to intervene not only on people and communities, but also within the environment in which the health problems take place.” “These approaches were focused in urban development, the implementation of community interventions, self-care programs, social prescription, social participation, development of public policies and basic services, governance, health behaviors approach, social capital, and mental health.”

Health Outcomes of Salutogenic Interventions[edit | edit source]

Although a number of different limitations were reported, it was found that 85% of studies reviewed had positive findings in relation to health outcomes with no adverse effects [10]. The specific results of each type of intervention were:

Individual Interventions led to:

- Decrease in HIV rates,

- Reduction in anxiety-related symptomatology,

- Increase in perception of quality of life,

- Higher personal satisfaction,

- Reduction in psychopathological symptomatology, and

- Reduction in eating disorders.”

Group Interventions showed improvements in different fields, such as:

- Reduction in disease prevalence and morbidity burden,

- Improvements in perceived health,

- Greater well-being and perceived quality of life,

- Decrease in psychopathological symptomatology, as well as other symptoms relating to anxiety and depression,

- Improved functional capacity,

- Lower burnout, and

- Reduction in Stress Symptomatology.

Mixed Interventions indicated progression linked to a;

- Reduction in pain-related symptomatology,

- Drop in insomnia and an increase in dream quality,

- Improvements in HRQoL,

- Increase of the functional capacity,

- Decrease of kinesophobia,

- Higher psychological, physical and social well-being, and

- Greater physical and mental health.”

Intersectoral Interventions derived to:

- Improvements in HRQoL,

- Increase in perceived well-being and self-rated health,

- Greater mental health,

- Reduction in depressive symptomatology,

- Decrease in preventable mortality for diabetes mellitus, influenza, heart disease and infant mortality.”

As can be seen, it is appropriate to say that the Salutogenic Model is more than just the measurement of sense of coherence [12]. “Salutogenesis can be seen as an umbrella concept with many different theories, concepts, approaches and strategies with salutogenic elements and dimensions.” [8]

Summary[edit | edit source]

Although more research needs to be conducted in respect of the salutogenic model, there is plenty of evidence that proves the model to be an effective health promotion resource that increases resilience and has an affirmative effect in the perceived physical and mental state, quality of life and wellbeing of people as individuals and even within their society.

Since it is a valid, reliable, multidimensional, and applicable instrument for measuring health in different cultures [22], more policies for health promotion through the model should be suggested and implemented at an international level. The interventions should continue to be focused not on disease but in salut.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Antonovsky, A.Health, Stress and Coping. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1979

- ↑ Antonovsky A, Maoz B, Dowty N, Wijsenbeek H. Twenty-five years later: A limited study of the sequelae of the concentration camp experience. Social Psychiatry. 1971 Dec 1;6(4):186-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00578367

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Antonovsky, A. Unraveling the Mystery of Health. How People Manage Stress and Stay Well. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1987.

- ↑ Lindström B, Eriksson M. Contextualizing salutogenesis and Antonovsky in public health development]. Health promotion international. 2006 Sep 1;21(3):238-44. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ Eriksson M. The sense of coherence in the salutogenic model of health. InThe handbook of salutogenesis 2017 (pp. 91-96). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ World Health Organization. Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion First International Conference on Health Promotion, 1986. Geneva: WHO. 2010.

- ↑ Eriksson M., Mittelmark M.B. (2017) The Sense of Coherence and Its Measurement. In: Mittelmark M. et al. (eds) The Handbook of Salutogenesis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_12

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Eriksson M, Mittelmark MB. The Sense of Coherence and Its Measurement 12. The handbook of salutogenesis. 2017;97. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_12

- ↑ Eriksson M., Mittelmark M.B. (2017) The Sense of Coherence and Its Measurement. In: Mittelmark M. et al. (eds) The Handbook of Salutogenesis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_12

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Álvarez ÓS, Ruiz-Cantero MT, Cassetti V, Cofiño R, Álvarez-Dardet C. Salutogenic interventions and health effects: a scoping review of the literature. Gaceta Sanitaria. 2020 Mar 18. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ Eriksson M. The Sense of Coherence in the Salutogenic Model of Health. 2016 Sep 3. In: Mittelmark MB, Sagy S, Eriksson M, et al., editors. The Handbook of Salutogenesis [Internet]. Cham (CH): Springer; 2017. Fig. 11.4, [The definition of generalized resistance resources (Antonovsky, , s. 103)]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK435812/figure/ch11.Fig4/ doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_11

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Idan O, Eriksson M, Al-Yagon M. The salutogenic model: The role of generalized resistance resources. InThe handbook of salutogenesis 2017 (pp. 57-69). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ Lindström B, Eriksson M. Salutogenesis. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health. 2005 Jun 1;59(6):440-2. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ Bauer GF, Roy M, Bakibinga P, Contu P, Downe S, Eriksson M, Espnes GA, Jensen BB, Juvinya Canal D, Lindström B, Mana A. Future directions for the concept of salutogenesis: a position article. Health Promotion International. 2020 Apr;35(2):187-95. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ Jensen BB, Dür W, Buijs G. The application of salutogenesis in schools. In The Handbook of Salutogenesis 2017 (pp. 225-235). Springer, Cham.https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ Vaandrager L, Kennedy L. The application of salutogenesis in communities and neighborhoods. InThe handbook of salutogenesis 2017 (pp. 159-170). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ Pelikan JM. The application of salutogenesis in healthcare settings. The Handbook of Salutogenesis. 2017 Jun 8:261. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/dal016

- ↑ Taylor JS. Salutogenesis as a framework for child protection: literature review. Journal of advanced nursing. 2004 Mar;45(6):633-43. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02954.x

- ↑ Aujoulat I, Mustin L, Martin F, Pélicand J, Robinson J. The application of Salutogenesis to health development in youth with chronic conditions. InThe Handbook of Salutogenesis 2017 (pp. 337-344). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_32

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Bonmatí-Tomas A, Malagón-Aguilera MC, Gelabert-Vilella S, Bosch-Farré C, Vaandrager L, García-Gil MD, Juvinyà-Canal D. Salutogenic health promotion program for migrant women at risk of social exclusion. International journal for equity in health. 2019 Dec 1;18(1):139. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1032-0

- ↑ Eriksson M., Mittelmark M.B. (2017) The Sense of Coherence and Its Measurement. In: Mittelmark M. et al. (eds) The Handbook of Salutogenesis. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-04600-6_12

- ↑ Eriksson M, Lindström B. Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale and the relation with health: a systematic review. Journal of epidemiology & community health. 2006 May 1;60(5):376-81. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2005.041616