Reactive Arthritis

Original Editors - Jennifer Colgan from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project. Top Contributors - Jennifer Colgan, Meredith Alvey, Kim Jackson, Admin, Vidya Acharya, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Rucha Gadgil, Wendy Walker, Claire Knott, Carina Therese Magtibay, 127.0.0.1 and Megan Sarason

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Reiter’s Syndrome is reactive arthritis that develops in response to an infection and characterized by a triad of arthritis, conjunctivitis, and nonspecific urethritis. It is considered an autoimmune disease marked by inflammatory synovitis and erosion at the insertion sites of ligaments and tendons. It commonly occurs after the presence of venereal disease process or enteric infection.[1][2][3]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Prevalence is difficult to establish due to lack of consensus regarding diagnostic criteria, the nomadic nature of the young target population, the under reporting of venereal disease, and the asymptomatic or milder course in affected women. [1]

Literature suggests that Reiter's Syndrome is more commonly seen in males, but recent studies suggest that the incidence in women is potentially underestimated. Women's symptoms tend to be less severe than men and women are prone to genitourinary diseases often causing a misdiagnosis. [1]

Individuals with the HLA-B27 genetic marker have an increased risk for developing Reiter's Syndrome following sexual contact or exposure to a bacterial infection. This history of infection (enteric or venereal) further increases the risk of developing Reiter's Syndrome. There is a strong prevalence of Reiter's Syndrome in individuals with HIV. The literature states that in patient's who are HIV positive, Reiter's Syndrome is more strongly correlated with male homosexuality than it is with people who have a history of injection drug use or other risky behaviours.[1][2]

Clinical Characteristics/ Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Urethritis, conjunctivitis, and arthritis are the three symptoms classically associated with Reiter’s Syndrome[1], [4], [2]. Urethritis discharge is intermittent and may be asymptomatic. Conjunctivitis is usually minimal. The arthritis is usually asymmetrical and polyarticular occurring in the large joints of the lower extremities, including the knees, ankles, and 1st metatarsophalangeal. In some cases, hand joints may be involved. Individuals can also present with fungal infections (uveitis, keratitis) of the cornea.[1]

Individuals can present with three musculoskeletal manifestations including acute inflammatory arthritis, inflammatory back pain, and enthesitis (inflammation of the tendon at its insertion onto bone). It is uncommon for all three musculoskeletal manifestations to present at one time. Enthesitis most commonly occurs at the insertion of the Achilles tendon onto the calcaneus causing heel pain. Enthesitis may also occur at the ischial tuberosity, iliac crest, tibial tuberosity, and ribs, with patient complaints of musculoskeletal pain at these sites. It is imperative that a complete and thorough history should be done on these patients during their initial evaluation to rule out presence of Reiter's Syndrome.[1][5]

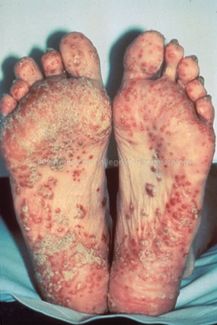

Reiter's Syndrome can have integumentary manifestations similar to psoriasis, a condition that causes dry, erythematous skin lesions that can occur in small patches or cover large surfaces. It commonly involves the toes, nails, and soles of feet.[5]

The initial illness typically resolves in 3-4 months, however, 50% of patients experience reoccurrence of symptoms and components of the syndrome over a period of years. Joint deformity and ankylosis, as well as sacroiliitis and spondylitis, may occur with chronic or recurrent RS. [2]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Reiter's Syndrome is associated with and maybe the presenting symptom of HIV.[1] Reiter's Syndrome is also associated with or triggered by Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia, Campylobacter, and Chlamydia.[2][3][4]

Medications[edit | edit source]

There is no evidence that antibiotic therapy changes the course of the disorder. NSAIDs are the primary intervention[1]. Below is a list of several more options[2][3][7].

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)[edit | edit source]

- Non-selective cyclo-oxygenase (COX) inhibitors - Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Diclofenac, Nabumetone, and many others

- Selective COX-2 inhibitor: Celecoxib

Corticosteroids[edit | edit source]

- Systemic steroids seldom used except in more severe cases, and only in low doses (5-10 mg/day)

- Intra-articular steroids for individual joints (e.g., triamcinolone acetonide) - may be useful in almost any inflamed joint

Antibiotics[edit | edit source]

- Antibiotics probably not useful in patients with reactive arthritis following enteric infection (salmonella, shigella, etc.)

- Antibiotics for non-gonococcal urethritis in patients with previous episodes will decrease risk of recurrence from 37% to 10%.

- A longer course of antibiotics (i.e., 3 months) may reduce the duration of acute illness following urogenital chlamydia infection; choices include:

– Doxycycline 100 mg qd

– Minocycline 100 mg bid

– Tetracycline 250 mg qid

Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs)[edit | edit source]

- Used in more severe reactive arthritis, but not needed nearly as often as in rheumatoid arthritis

- Sulfasalazine 500-1,500 mg bid

- Methotrexate 7.5-25 mg weekly in single dose

- DMARDs used rarely - all anecdotally, none well studied

- Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg bid

- Cyclosporine A 2.5 mg/kg/day

- Auranofin 3 mg bid

- Injectable gold (Solganol 50 mg q1-4 weeks)

- Azathioprine 50 mg bid-tid

- Leflunomide 10-20 mg qd (with or without loading of 100 mg for 3 days)

Biological Therapies[edit | edit source]

These are all anecdotally and only normally reserved for rare, severe cases

- Etanercept 25 mg sq twice weekly; may be given alone, but usually used as addition to Methotrexate

- Infliximab 3 mg/kg IV - at weeks 0, 2, 6, and then every 8 weeks; dose can be increased up to 10 mg/kg; almost always given in conjunction with Methotrexate

- Adalimumab 40 mg sq every 2 weeks; maybe given alone, but usually added to Methotrexate

- Golimumab 50 mg sq every 4 weeks; maybe given alone, but usually added to Methotrexate

- Other biologics (certolizumab, abatacept, rituximab) have potential benefit, but not as extensively studied as others

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Due to various manifestations of the disease occurring at different times, a diagnosis may take months to establish. The combination of peripheral arthritis with urethritis lasting longer than 1 month is necessary before the diagnosis can be confirmed. Laboratory tests typically reveal an aggressive inflammatory process. Elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein are detected. Other common findings include thrombocytosis and leukocytosis. The presence of certain bacteria in urine samples, genital swabs, and stool cultures can be used to identify the infection through laboratory tests.

Positive gonococcal cultures and a rapid response to penicillin therapy differentiate acute gonococcal arthritis from Reiter's Syndrome in sexually active young patients, as individuals with Reiter's Syndrome will not respond to the penicillin treatment. Radiographic abnormalities may include asymmetric involvement of the lower extremity diarthroses, amphiarthroses, symphyses, and entheses in the affected joints. Poorly defined bony erosions with adjacent bony proliferation or paravertebral ossification may present on x-ray review. [1][2][3][4]

An MRI is the diagnostic imaging of choice to help diagnose Reiter's Syndrome. The affected bone will present with a moth-eaten appearance, bony expansion, and loss of cortical definition. Bone scans can also be used in conjunction with an MRI and will exhibit increase uptake. The bony destruction lesions can cross epiphyseal growth plates, joints, and discs.[8]

Causes[edit | edit source]

Reiter's Syndrome can not be transmitted from person to person. However, the bacteria that triggered the disease can be passed on from one person to another.[4] Reiter’s Syndrome usually follows venereal disease or an episode of bacillary dysentery, which is a bacterial infection characterized by blood in the stool. Up to 85% of people with Reiter's possess the HLA-B27 alloantigen. Individuals with the appropriate genetic background can develop Reiter's Syndrome through an enteric infection.[1]

Bacteria that most often cause infections and Reiter's syndrome are Chlamydia, Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia, and Campylobacter. These can be manifested from sexually transmitted diseases or contaminated food.[2][4]

Systemic Involvement [edit | edit source]

Musculoskeletal manifestations are acute inflammatory arthritis, inflammatory back pain (in severe cases), and enthesitis. Enthesitis is inflammation at the insertion of tendons and ligaments into bones. Dactylitis or "sausage digit", plantar fascitis, and Achilles tendinitis are the most common sites.[1][2][3][4]

Skin lesions are very similar to those of psoriasis[2][3]

Constitutional symptoms include fatigue, malaise, fever, and weight loss[2][3][4]

Cardiovascular involvement with aortitis, aortic insufficiency, and conduction defects occur rarely.[2]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Tetracyclin or erythromycin 500 mg taken orally 4 times per day for 10 days is recommended in treatment of patients with Reiter's Syndrome due to sexual exposure. No treatment is necessary for conjunctivitis or mucocutaneous lesions, although topical opthalmic glucocorticosteroidsiritis may be required to treat iritis. Arthritis is treated with NSAIDs in doses similar to those used for rheumatoid arthritis. Enthesopathy may need to be treated with local injection of corticosteroids, to decrease inflammation at the site of the injection.[2][7]

Surgery is rarely indicated but may include synovectomy, fusion, or tendon repair.[7]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Physical Therapy is helpful during the recovery phase of the disease (after exacerbation of symptoms has ceased). Physical Therapy should follow a program similar to that given to a patient with arthritis.

- Patient education - this is necessary to promote joint protection and proper body mechanics when performing daily activities to maintain joint integrity.

- Exercise regimen - that includes regular aerobic activity, as well as exercises that promote the joint range of motion and muscles strengthening should be utilized.

- Aerobic exercise should include low impact activities, such as swimming, walking, or recumbant bike, depending on the patient's cardiovascular level.

- Strengthening should target muscles surrounding the affected joints with the purpose of improving its support system.

Immobilization and inactivity are discouraged as they can lead to decreased range of motion, contractures, joint stiffness, decreased muscle strength and decreased flexibility, as well as overall decreased cardiovascular fitness, which can cause a cascade effect on other body systems. Goals of treatment should include pain relief, improved activities of daily living, reduce joint swelling, prevention of joint damage and disability.[4][7][9]

Differential Diagnosis [edit | edit source]

Below is a list of other conditions with similar symptoms:[10] [3]

- Psoriatic Arthritis

- Pityriasis Rubra Pilaris

- Lichen Planus

- Lupus Erythematosus

- Dermatomyositis

- Behcet's Disease

- Arthritis associated with Gonococcal Disease

- Rheumatoid Arthritis

- Septic Arthritis

- Mycosis Fungoides

- Subcorneal Pustulosis of Sneddon-Wilkinson

- Atopic Dermatitis

- Acute Exanthematous Pustulosis

- Other causes of Exfoliative Dermatitis

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd ed. St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; 2009.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Porter RS, Kaplan JL. The Merck manual of diagnosis and therapy. Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp.; 2011.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 Kasper DL, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL. Harrison's Manual of Medicine. 16th ed. McGraw-Hill, 2005

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 4.6 4.7 Developed by R. Reiter's Syndrome. CRS - Adult Health Advisor [serial on the Internet]. (2009, July), [cited April 5, 2010]; 1. Available from: Health Source - Consumer Edition.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral, 5th ed. St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier; 2013.

- ↑ Reiter Syndrome Health Byte LIVESTRONG.COM Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=3&v=mjLvaP82BHo

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Reactive Arthritis (Reiter's Syndrome). Treatment Strategies. 2009 Jan 10. In ProQuest Medical Library. Cited 2010, Mar 20. Available from: http://www.proquest.com/;DocumentID:1871950901

- ↑ Lonnemann E. Spondylogenic & Immunological Disorders. [PowerPoint]. Louisville, KY: Bellarmine University Doctorate of Physical Therapy Program; 2014.

- ↑ Mayoclinic.com Website. Reactive Arthritis: Treatment and Drugs. Accessed March 4, 2010. Available at:http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/reactive-arthritis/DS00486/DSECTION=treatments-and-drugs

- ↑ ↑ Reiter Syndrome. In:ProQuest Medical Library. Avaiable from: http://www.proquest.com/;DocumentID:1871990641. Cited 2010 Mar 20