Principles of Amputation

Original Editor - Lucy Coughlan as part of the WCPT Network for Amputee Rehabilitation Project

Top Contributors - Admin, Aicha Benyaich, Tarina van der Stockt, Rachael Lowe, Tony Lowe, Kim Jackson, Shaimaa Eldib, Sheik Abdul Khadir, Rucha Gadgil, Lauren Lopez, Simisola Ajeyalemi, Amrita Patro, Wanda van Niekerk and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Amputation is the cutting off or the removal of limb/extremity or part therof. [1] by trauma, prolonged constriction or surgery (see Pathology leading to amputation). As a surgical measure, it is used to control pain or a disease process in the affected limb such as a malignancy, infection or gangrene. In some cases an amputation is carried out on individuals as a preventative surgery for such problems and other people are born with amputations due to congenital disorders (see Paediatric limb deficiency)

Every care should be taken to assure that the amputation is done only when clinically indicated. Amputation should only be considered if the limb is non-viable (gangrenous or grossly ischemic, dangerous, malignancy or infection), or non-functional[2].

A well-planned and executed amputation can remove a painful, dysfunctional limb and allow rehabilitation with a prosthetic limb to a functional, painless state. In this regard, amputation surgery may be considered reconstructive surgery, with results similar to amputation of an arthritic femoral head and prosthetic replacement (total-hip replacement)[3].

Assessment for amputation[edit | edit source]

A decision to amputate a limb should be made through discussion with the interdisciplinary team - including the patient - wherever possible; in an emergency situation the decision should made based on medical need. There are a number of different investigations that can be carried out to assess the need for an amputation; these examinations assess the bones and soft tissues to establish limb viability.

- X-ray – images of bones to view fractures or disease

- Computerised Tomography (CT) scan – detailed images of bone, tissue and blood vessels

- Angiogram – outlines blood vessels

- Doppler ultrasound – occlusion of blood vessels

- Venogram and arteriogram – detailed imaging of blood vessels

These investigations will help the surgeons to find out if the blood supply to the limb is intact. The lower limb is supplied by the popliteal artery which subdivides into the:

- Posterior tibial artery

- Anterior tibial artery

- Fibular artery

In vascular disease these arteries can become blocked or narrowed over time which reduces the circulation to the legs; this can cause pain, ulceration and blackened areas. If left untreated this can lead to gangrene or infection and an amputation is needed to avoid this becoming life threatening.

In trauma one or more of these blood vessels may be ruptured beyond repair due to the nature of the injuries sustained – e.g. in a car accident, gunshot wound or blast. In this situation an amputation is performed as the limb does not have any blood supply beyond the level of injury and is therefore deemed non-viable.

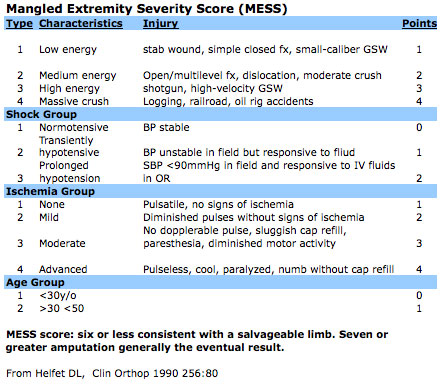

There are a number of injury severity scores that may be used in conjunction with clinical investigations to establish the likelihood of limb salvage. Examples of this include:

- Nerve Injury, Ischemia, Soft-Tissue Injury, Skeletal Injury, Shock, and Age of Patient Score (NISSA)[4]

- Limb salvage index (LSI) [5]

- Mangled Extremity Severity Score (MESS)[6]

Once a decision has been made to remove part of a limb the level of amputation needs to be decided; this can have significant consequences so there are a number of factors to take into account when planning the surgery:

- Boundary of dead or diseased tissue - if the infection or disease is not completely eradicated the patient may need to undergo further operations or treatment so it is important that the amputation is done at a level where this can be achieved

- Suitability for prosthesis - if the patient is likely to be a candidate for prosthetic rehab the level of amputation needs to be carefully considered

- Mobility and function - it is useful to consider the patients’ pre-morbid level of mobility and function

- Cosmesis - length and shape of stump affect the aesthetic appearance

Levels of Lower Limb Amputations[edit | edit source]

Amputations of the foot[edit | edit source]

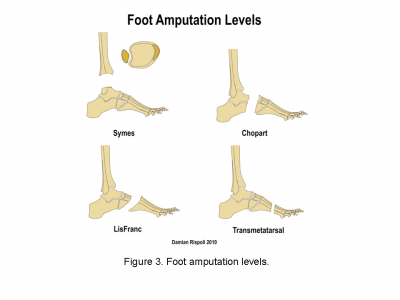

- Toe - amputation through phalanges or disarticulation of metatarsal-phalangeal joint

- Ray - amputation of phalanges and some or all of corresponding metatarsal

- Transmetatarsal - partial foot amputation through metatarsals

- Tarsometatarsal (Lisfranc) - amputation of the forefoot at the tarsometatarsal line.

- Mid-tarsal (Chopart) - amputation between the talus and the calcaneus proximally and the cuboid and the navicular distally.

- Ankle disarticulation (Symes) – amputation through the ankle joint

Advantages

- Range of prosthetic options such as insoles, toe fillers or ankle-foot orthosis (exception for ankle disarticulation)

Disadvantages

- May need further surgery in future

- Can lead to skin breakdown and joint pain

- Cosmesis might be not accepted by the patient

|

|

|

Read more:

Transtibial / below knee amputation[edit | edit source]

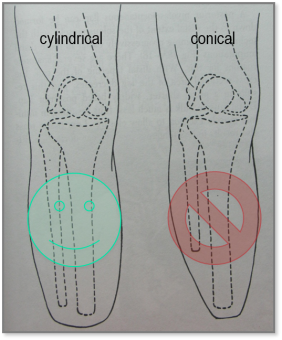

This amputation is done through the tibia and fibula, measurements are taken and flap lines marked out. The surgeon dissects through the skin to then isolate and ligate the nerves and blood vessels. In order to minimise the risk of neuropathic pain (see complications) the nerves are dissected on tension so the end will retract back into the tissues where they can heal away from the stump end. The tibia is dissected using an oscillating saw – optimum length of residual bone is approximately 14-16cm; the tibia should be bevelled at approximately 45° to remove sharp anterior edge, the fibula should ideally be approx. 1-2 cm shorter than the tibia on a perpendicular axis. Preferred flap technique of surgeon is then used to close the wound and create functional stump - options include skew flap, long posterior flap, sagittal flap or medial flap.

Advantages

- Preservation of the knee joint

- Candidates for patella tendon bearing prosthesis

Disadvantages

- At risk of knee flexion contractures (see complications)

- May need ‘bone bridge’ surgery due to distal fibula pain (see complications)

|

|

This video shows one example of how a transtibial amputation can be performed.

Read more:

Knee disarticulation amputation[edit | edit source]

Amputation through the knee joint:

Advantages

- Long lever prevents contractures and allows consequently the movement control

- Maintains muscle length and strength

- Preserves growth plates in children

- Candidates for end bearing prosthesis

- Conseve condyles and the patella

- Proprioceptionand better distribution of pressure

Disadvantages

- Bulky prosthesis (see complications)

- Poor cosmesis as knee mechanism is distal to knee joint (see complications)

Surgery video for through knee amputation:

Read more:

- Knee Disarticulation: Surgical Procedures

- The Knee Disarticulation: It's Better When It's Better and It's Not When It's Not

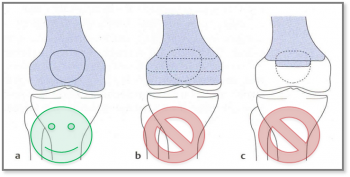

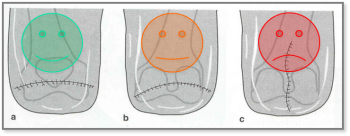

Transfemoral / above knee amputation[edit | edit source]

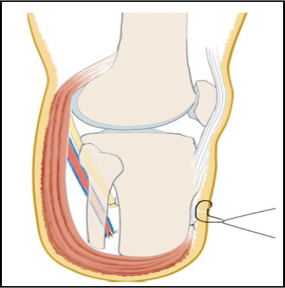

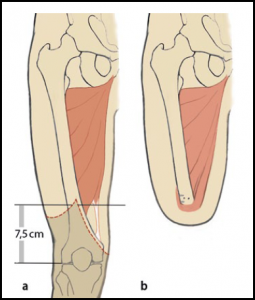

This amputation is done through the femur, measurements are taken and flap lines marked out. The surgeon dissects through the skin to then isolate and ligate the nerves and blood vessels. In order to minimise the risk of neuropathic pain (see complications) the nerves are dissected on tension so the end will retract back into the tissues where they can heal away from the stump end. The femur is dissected on its perpendicular axis using an oscillating saw.

Optimum length of residual bone is approximately 7.5-10cm proximal to the superior border of patella. Very short trans-femoral stumps often end up in abduction because there is an imbalance between the adductor and abductor muscles.

With a transfemoral amputation the distal attachments of the thigh muscles is lost, in order to preserve their function and length a myodesis may be performed to anchor the adductor (and sometimes hamstring) muscles to bone. The hamstrings and quadriceps may then be sutured together over the distal end of the femur – a technique called a myoplasty. It is a myopklasty of the antagonist muscles to help pad the end of the stump to perform Gottchaltk myodesis (adductor magnus trans-osseously fixed and covering the distal femoral end)

Advantages and Disadvantages

For Long stump (a)

- best lever

- better muscular balance while preserving the strength of the adductors

- energy efficient

- candidate for ischial tuberosity bearing prosthesis

Medium-length stump (b)

- reduced strength of the adductors

- increased flexion and abduction

- increased energy expenditure

Short stump (c)

- weak adductor muscles, causing severe imbalance

- position of the stump often ends up in flexion and abduction

- causes massive energy expenditure (effort) and prosthesis can be heavy

|

|

This video shows one example of how a transfemoral amputation can be performed

Read more:

- Transfemoral Amputation: Surgical Procedures

- The Transfemoral Amputation Level, Part 2, Surgery and Postoperative Care

Other types of amputation in the lower limb[edit | edit source]

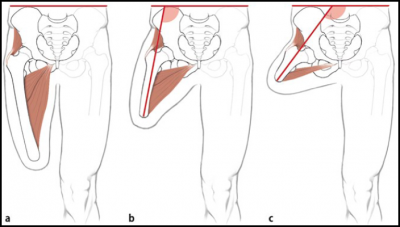

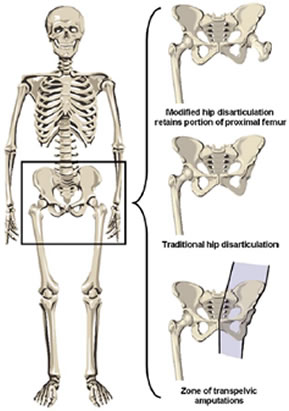

Hip disarticulation[edit | edit source]

Hip disarticulation is amputation of the whole lower limb through the hip joint. A traditional hip disarticulation is done by separating the ball from the socket of the hip joint, while a modified version retains a small portion of the proximal (upper) femur to improve the contours of the hip disarticulation for sitting. A hip disarticulation results most often from trauma, tumors and severe infections, such as necrotizing fasciitis (commonly referred to as flesh-eating bacteria). Less often, it results from vascular disease and complications of diabetes. [7] Many are wheelchair users but can be considered for ischial tuberosity bearing prosthesis.

Hemi-pelvectomy (hindquarter)[edit | edit source]

Amputation of the whole lower limb and ipsilateral hemi-pelvis[8] This type of amputation is most rare. They are likely to be a wheelchair user, some are considered for a trunk and contralateral ischial tuberosity weight bearing prosthesis

Read more:

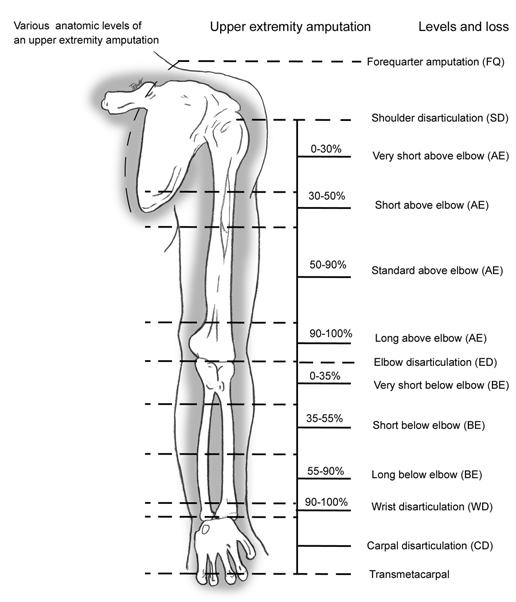

Upper Limb Amputations[edit | edit source]

54% of all upper limb amputations are as a result of trauma; in comparison only 3% of lower limb amputations are as a result of trauma. Upper limb amputations are seen more rarely than lower limb amputations.

Levels of upper limb amputations:

- Fingers

- Partial hand

- Wrist disarticulation

- Transradial

- Elbow disarticulation

- Transhumeral

- Shoulder disarticulation

- Scapulo-thoracic dissociation (forequarter)

There are a range of different prosthetics available for the upper limb; these range from hooks to passive orthotics that might mainly serve an aesthetic purpose to fully mechanical and functional limbs.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Definitions of amputation related terms from the Amputee Coalition

- Questions to Ask Your Surgeon

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Limb Loss Definitions. Fact Sheet. Amputee Coalition 2008. http://www.amputee-coalition.org/resources/limb-loss-definitions/ [accessed 24 Sep 2017]

- ↑ Clinical Practice Guideline for Rehabilitation of Lower Limb Amputation. Department of Veterans Affairs, Department of Defence. 2007

- ↑ Thomas J. Moore. Planning for Optimal Function in Amputation Surgery. Chapter 3 - Atlas of Limb Prosthetics: Surgical, Prosthetic, and Rehabilitation Principles. 2002

- ↑ McNamara et al (1994) Severe Open Fractures of the Lower Extremity: A Retrospective Evaluation of the Mangled Extremity Severity Score (MESS). J Orthop Trauma 8: 81-7

- ↑ Russell et al (1991) Limb Salvage Versus Traumatic Amputation A Decision Based on a Seven-part Predictive Index Ann Surg. 213: 473-81

- ↑ Johansen et al (1990) Objective Criteria Accurately Predict Amputation following Lower Extremity Trauma. J Trauma.30: 568-73

- ↑ Douglas G. Smith. Higher Challenges: The Hip Disarticulation and Transpelvic Amputation Levels. inMotion, January/February 2005, 15(1).

- ↑ Robert E. Tooms and Frederick L. Hampton. Hip Disarticulation and Transpelvic Amputation: Surgical Procedures. Chapter 21A In: Atlas of Limb Prosthetics: Surgical, Prosthetic, and Rehabilitation Principles.