Preventing Dementia and Cognitive Decline

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The amount of people suffering from cognitive impairment or any type of dementia has been constantly on the rise. Around 50 million people suffer from dementia worldwide, with 10 million new cases every year. Some say the rise is due to the prolonged life expectancy, but it is important to note that although age is the strongest known risk factor for dementia, it is not a normal and inevitable consequence of aging. Dementia is one of the major causes of disability and dependency among older people. It has a physical, psychological, social and economic impact on people with dementia, but also their carers, families and society at large.[1] As of date, no effective treatment of dementia and cognitive decline have been found - leaving an urgent need for preventive interventions.

General[edit | edit source]

The term dementia includes several diseases that are mostly progressive and affect the memory, other cognitive abilities and behaviour. The disease interferes significantly with one's ability to maintain activities of daily living. The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer disease (60-70% of prevalence). Other major forms of dementia include vascular dementia, Lewy bodies and a group of diseases that contribute to frontotemporal dementia. Mixed forms often coexist and boundaries between different forms of dementia are indistinct making it difficult to diagnose.[2]

With both mild cognitive impairment (MCI) and dementia there is objective evidence of cognitive impairment. The main distinction between the two terms is that with dementia, more than one cognitive domain is involved and that substantial interference with daily life is evident. Individuals with MCI have objective evidence of declination in cognitive impairment from the past, but they function independently or nearly so in their daily lives in a manner that is indistinguishable from the past.[3]

A common misconception is that dementia exclusively affects older people. Young onset dementia (the onset of symptoms before the age of 65 years) accounts for up to 9% of prevalence.[4]

Research has shown a relationship between the development of cognitive impairment and lifestyle-related risk factors that are shared with other noncommunicable diseases. These risk factors include:

- Physical inactivity

- Obesity

- Unbalanced diet

- Tobacco use

- Harmful use of alcohol

- Diabetes Mellitus

- Mid-life hypertension

- Cardiovascular pathology

Other risk modifiable risk factors that are specific to dementia are:

- Mid-life depression

- Low educational attainment

- Social isolation

- Cognitive inactivity

In addition, non-modifiable genetic risk factors exist that increase the risk of developing dementia. It is worth noting that although a family history of dementia is common, the lifetime risk of dementia for relatives of most people with dementia is around 20%, compared with about 10% in the general population.[5]

Economics[edit | edit source]

The financial impact of dementia is significant, both for patients and their families and on a global scale. Families face cost of health and social care and reduction or loss of income. In 2015, the costs for direct medical, social care costs and costs of informal care for dementia were estimated at US$818 billion (1.1% of the GDP). The expected rise in costs for people with dementia worldwide is US$2 trillion by 2030. This total could undermine global social and economic development and overwhelm health and social services.[1]

Prevention[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization wrote the global action plan on the public response to dementia, in which there lies a big role for the prevention of dementia. Their vision is as follows:

"The vision of the global action plan on the public health response to dementia is a world in which dementia is prevented and people with dementia and their carers live well and receive the care and support they need to fulfil their potential with dignity, respect, autonomy and equality." - WHO, Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017-2025 (2017)

As mentioned before, there is a relationship between dementia, MCI and noncommunicable disease and lifestyle-related risk factors. By reducing the level of exposure of both individuals and populations to the modifiable risk factors (beginning in childhood), the capacity to make healthier choices can be strengthened.

The most important measures are:

- Increasing physical activity

- Preventing and reducing obesity

- Promotion of balanced and healthy diets

- Cessation of tobacco use and the harmful use of alcohol

- Social engagement

- Promotion of cognitively stimulating activities and learning

- Prevention and management of diabetes, hypertension and depression

[edit | edit source]

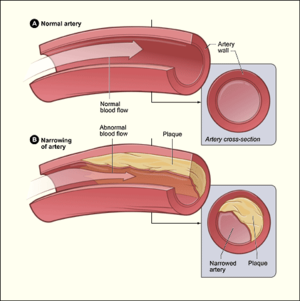

A healthy lifestyle of the whole lifespan considerably reduces the risk of dementia later in life.[6] Accumulating evidence indicates a close relation between the body and mind in the development of dementia. The brain is a highly vascularised organ and particularly vulnerable to impairment in blood flow and vascular pathology. Cardiovascular disease and dementia often occur in the same person, and share common risk factors.[7][8][9] Cohort studies show that inter-cranial atherosclerosis increases the chance of dementia, independent of Alzheimer's disease pathology and cerebral infarcts.[10]

The evidential support for a central role for systemic atherosclerosis in cognitive decline is growing and is suggested that even subclinical atherosclerotic pathology might be associated with poor vascular and brain health. In recent research, the presence of heart disease and heart failure has been associated with a 27% and 60% increased risk fo dementia.[11] Although the etiologic role of atherosclerosis in Alzheimer's disease is still controversial, several studies have found correlations between carotid atherosclerosis and Alzheimer's disease.[12][13] Nine out of ten studies included in a systematic review by Chang et al. linked asymptomatic carotid stenosis to cognitive dysfunction, which suggests that subclinical changes are at play in cognitive decline when atherosclerosis is present.[14]

Sedentary behaviours increase psychological stress and are, due to disrupted homeostasis in blood pressure and glycemic levels, a greater vascular and metabolic burden.[15] Physical activity should be recommended to reduce the risk of cognitive decline.[2][16][17]

Research has shown that three types of exercise should be included in an individual's regular routine:

- Sustained aerobic exercise

- Strength, weight or resistance training

- Flexibility and balance training

Tobacco is the major risk factor for cancer, cardiovascular disease and dementia. With the global prevalence of smokers being around 30%, about 14% of all cases of Alzheimer's disease are attributable to smoking.[18] The evidence to the harmful effects on smoking on cognition are strong and show a dose-response effect.[9]

Alcoholic dementia and Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome are well-known possible consequences of excessive and long-term alcohol consumption. There has been found a link between milder forms of MCI and dementia and alcohol abuse, which seems to cause neurotoxicity and neuroinflammation but also affects the brain directly by promoting nutritional deficiency.[19] Interestingly, light-to-moderate alcohol consumption is linked with a reduced risk of cardiovascular morbidity and cognitive decline and dementia with respect to both alcohol abuse and a completely alcohol-free diet.[20]

Finally, more and more evidence is emerging about the effect of diet on risk of cognitive impairment and dementia. Studies have pointed to the protective effect of some nutrients, including omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamins such as the B complex (vitamins B6, B12 and folate), antioxidants (vitamin A, C and E) and vitamin D.[21][22][23] Recently, research has focused on dietary patterns rather than single nutrients and their association with cognition and evidence suggests that healthy dietary patterns such as the Mediterranean diet is associated with less cognitive decline and a lower risk of dementia or Alzheimer's disease.[24][25][26] Dietary patterns rich in red meat and sugar-rich foods have been associated with higher mortality. According to research on diet patterns, some key ingredients that are associated with longevity and better cardiometabolic and cognitive health can be identified. These include a high intake of fruit, vegetables, fish, (whole) grains, legumes/ pulses and potatoes.[27] It should be noted however, that the majority of findings with regard to the Mediterranean diet provide evidence for a correlation, and not a cause-and-effect relation.[28][29]

Role for physiotherapy in preventing dementia or MCI[edit | edit source]

When it comes to preventing not only dementia but also other non-communicable lifestyle-related diseases, there is an opportunity and expanding role for physiotherapists to influence the risk factors. Health promotion should be lifespan focussed and can be done through education, advice and exercise. The physiotherapist could use the intervention mapping (IM) protocol to develop a programme and use Motivational Interviewing to empower the individual's motivation and self-commitment to behavioural change. A randomised controlled study suggests that action observation (motor-related information available through the visual function) with gait training provides more significant benefits for gait and cognitive performances in the elderly with mild cognitive impairment[30].

Focus on the benefits of a healthy lifestyle, and make it a goal for your patient to meet the recommended levels of physical activity:

- Adults aged 18–64 should do at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week or do at least 75 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity throughout the week or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity.

- Aerobic activity should be performed in bouts of at least 10 minutes duration.

- For additional health benefits, adults should increase their moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity to 300 minutes per week, or engage in 150 minutes of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity per week, or an equivalent combination of moderate- and vigorous-intensity activity.

- Muscle-strengthening activities should be done involving major muscle groups on 2 or more days a week.[31]

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

The vast majority of research tend to support that physical activity is a promising intervention for the prevention and non-pharmacological treatment of dementia. Results vary according to the particular characteristics as type, intensity, frequency and duration.[32] Preventing stroke, treating heart diseases, and reducing vascular risk factor burden would therefore represent a powerful strategy to reduce the burden of dementia worldwide.[33] All preventive strategies taken in dementia prevention need to be implemented in a life-course approach, such as control of hypertension, obesity and other modifiable risk factors.[34] The results are stronger when these factors are managed in midlife, compared to later life. International guidelines on physical activity are evidence-based to reduce the negative consequences of a unhealthy lifestyle and following these guidelines is recommended.

An important take-home message, based on various studies, is that it is never too late to start prevention. Preventive interventions that improve the risk profile even of older individuals can delay the onset of MCI and dementia.[9]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017-2025, WHO

- Dementia

- Alzheimer's Disease

- Lewy Body Disease

- Non-Communicable Diseases

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali GC, Wu Yutzu, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2015. The global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, cost and trends. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2015

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Prince M, Albanese E, Guerchet M, Prina M. World Alzheimer Report 2014. Dementia and risk reduction: an analysis of protective and modifiable risk factors. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; 2014

- ↑ Knopman, David S., and Ronald C. Petersen. "Mild cognitive impairment and mild dementia: a clinical perspective." Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Vol. 89. No. 10. Elsevier, 2014.

- ↑ Alzheimer’s Disease International and WHO. Dementia: a public health priority. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012

- ↑ Loy, Clement T., et al. "Genetics of dementia." The Lancet 383.9919 (2014): 828-840.

- ↑ Winblad, Bengt, et al. "Defeating Alzheimer's disease and other dementias: a priority for European science and society." The Lancet Neurology 15.5 (2016): 455-532.

- ↑ Grande, Giulia, et al. "Co-occurrence of cognitive impairment and physical frailty, and incidence of dementia: Systematic review and meta-analysis." Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews (2019).

- ↑ Qiu, Chengxuan, and Laura Fratiglioni. "A major role for cardiovascular burden in age-related cognitive decline." Nature Reviews Cardiology 12.5 (2015): 267.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Grande, Giulia, Chengxuan Qiu, and Laura Fratiglioni. "Prevention of dementia in an ageing world: Evidence and biological rationale." Ageing Research Reviews (2020): 101045.

- ↑ Dolan, Hillary, et al. "Atherosclerosis, dementia, and Alzheimer disease in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging cohort." Annals of neurology 68.2 (2010): 231-240.

- ↑ Wolters, Frank J., et al. "Coronary heart disease, heart failure, and the risk of dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis." Alzheimer's & Dementia 14.11 (2018): 1493-1504.

- ↑ Hofman, Albert, et al. "Atherosclerosis, apolipoprotein E, and prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in the Rotterdam Study." The Lancet 349.9046 (1997): 151-154.

- ↑ Yan, Z., et al. "Carotid stenosis and cognitive impairment amongst older Chinese adults living in a rural area: a population‐based study." European journal of neurology 23.1 (2016): 201-204.

- ↑ Chang, Xue-Li, et al. "Association between asymptomatic carotid stenosis and cognitive function: a systematic review." Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 37.8 (2013): 1493-1499.

- ↑ Panahi, Shirin, and Angelo Tremblay. "Sedentariness and health: Is sedentary behavior more than just physical inactivity?." Frontiers in public health 6 (2018): 258.

- ↑ WHO. "Risk reduction of cognitive decline and dementia: WHO Guidelines." (2019).

- ↑ Ahlskog, J. Eric, et al. "Physical exercise as a preventive or disease-modifying treatment of dementia and brain aging." Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Vol. 86. No. 9. Elsevier, 2011.

- ↑ Norton, Sam, et al. "Potential for primary prevention of Alzheimer's disease: an analysis of population-based data." The Lancet Neurology 13.8 (2014): 788-794.

- ↑ Day, Ed, et al. "Thiamine for Wernicke‐Korsakoff Syndrome in people at risk from alcohol abuse." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 1 (2004).

- ↑ Ruitenberg, Annemieke, et al. "Alcohol consumption and risk of dementia: the Rotterdam Study." The Lancet 359.9303 (2002): 281-286.

- ↑ Hooshmand, Babak, et al. "Association of vitamin B12, folate, and sulfur amino acids with brain magnetic resonance imaging measures in older adults: a longitudinal population-based study." JAMA psychiatry 73.6 (2016): 606-613.

- ↑ Rutjes, Anne WS, et al. "Vitamin and mineral supplementation for maintaining cognitive function in cognitively healthy people in mid and late life." Cochrane database of systematic reviews 12 (2018).

- ↑ McCleery, Jenny, et al. "Vitamin and mineral supplementation for preventing dementia or delaying cognitive decline in people with mild cognitive impairment." Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 11 (2018).

- ↑ Prinelli, Federica, et al. "Specific nutrient patterns are associated with higher structural brain integrity in dementia-free older adults." NeuroImage 199 (2019): 281-288.

- ↑ Shakersain, Behnaz, et al. "Prudent diet may attenuate the adverse effects of Western diet on cognitive decline." Alzheimer's & Dementia 12.2 (2016): 100-109.

- ↑ Sindi, Shireen, et al. "Healthy dietary changes in midlife are associated with reduced dementia risk later in life." Nutrients 10.11 (2018): 1649.

- ↑ Kiefte-de Jong, Jessica C., John C. Mathers, and Oscar H. Franco. "Nutrition and healthy ageing: the key ingredients." Proceedings of the Nutrition Society 73.2 (2014): 249-259.

- ↑ van de Rest, Ondine, et al. "Dietary patterns, cognitive decline, and dementia: a systematic review." Advances in nutrition 6.2 (2015): 154-168.

- ↑ Petersson, Sara Danuta, and Elena Philippou. "Mediterranean diet, cognitive function, and dementia: a systematic review of the evidence." Advances in Nutrition 7.5 (2016): 889-904.

- ↑ Rojasavastera R, Bovonsunthonchai S, Hiengkaew V, Senanarong V. Action observation combined with gait training to improve gait and cognition in elderly with mild cognitive impairment A randomized controlled trial. Dementia & Neuropsychologia. 2020 Jun;14(2):118-27.

- ↑ World Health Organization. "Information sheet: Global recommendations on physical activity for health 5-17 years old." Geneva: World Health Organization (2011).

- ↑ Kouloutbani, K., K. Karteroliotis, and Antonis Politis. "The effect of physical activity on dementia." Psychiatrike= Psychiatriki 30.2 (2019): 142-155.

- ↑ Hachinski, Vladimir, et al. "Preventing dementia by preventing stroke: The Berlin Manifesto." Alzheimer's & Dementia 15.7 (2019): 961-984.

- ↑ Kivipelto, Miia, Francesca Mangialasche, and Tiia Ngandu. "Lifestyle interventions to prevent cognitive impairment, dementia and Alzheimer disease." Nature Reviews Neurology 14.11 (2018): 653-666.