Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Therapy

Original Editor - Patti Cavaleri

Top Contributors - Patti Cavaleri, Aminat Abolade and Candace Goh

Description

[edit | edit source]

Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is type of cellular therapy that falls under regenerative medicine. There has been growing interest and research in using PRP injections to treat pain and promote tissue healing for musculoskeletal conditions, as well as skin rejuvenation, treatment for hair loss, breast augmentation, and wound rejuvenation[1][2]. The addition of PRP to a site is believed to initiate tissue repair through natural healing response to tissue stimulation, synthesis of new connective tissues, and revascularization. Due to the use of autologous blood, there are limited adverse reactions compared to other injection based therapies, such as corticosteroid injections[1].

PRP is typically classified into 3 groups[1]:

- Pure platelet-rich fibrin (P-PRF)

- Leukocyte-rich PRP (LR-PRP): pro-inflammatory with high concentration of growth factors[3]

- Leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP): anti-inflammatory[3]

Indication

[edit | edit source]

Some studies have found PRP to be more beneficial in treatment of osteoarthritis (OA) compared to saline, hyaluronic acid, or corticosteroids[2]. Tendinopathy disorders that have also demonstrated good results from PRP in clinical trials for rotator cuff disorders, gluteal tendinopathy, and lateral epicondylalgia[2].

Achilles Tendinopathy: A 2019 meta-analysis assessed 5 randomized controlled trials that examined the effect of PRP on Achilles tendinopathy compared to placebo treatment. The only significant difference was found at 6 weeks post treatment for higher function in the PRP group compared to the placebo group. However, further follow-ups showed no significant difference between groups[4].

Knee Osteoarthritis: A 2019 systematic review and meta-analysis examined the effects of PRP and hyaluronic acid treatments in knee OA[3]. The review compared 18 randomized controlled trials. The PRP groups found larger improvements in short term and long term outcome measures compared the hyaluronic acid groups. The amount of injections and formulas used varied between trials. LP-PRP injections are recommended in some systematic reviews as the preferred type of injection[1].

Lateral Epicondylalgia: Randomized control trials show better improvements in pain and function for long term results from PRP injections compared to steroid injections[5].

Ulnar Collateral Ligament Tear (UCL): Partial and complete tears of the UCL are commonly seen in overhead athlete sports, such as baseball. Case series report good functional outcomes and return to sport with the combination of PRP and physical therapies[6].

Contraindications[edit | edit source]

Contraindications for PRP therapy include[5]:

- Immunocompromised state

- Active infection

- Inability to understand and comply with post-procedure modifications

- Coagulopathy or anticoagulation

- Prosthetic joints

- Prosthetic hardware infection

- Severe cases of advanced OA

Procedure[edit | edit source]

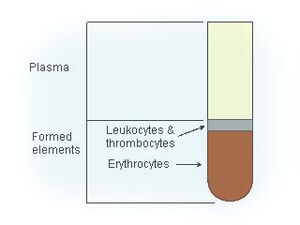

For the procedure, blood is collected from a patient and placed into a centrifuge to separate the blood into it's components. A portion of the sample is then injected into the targeted site. There is not currently a recognized standard for the ideal formula of PRP, platelets, white blood cells, and other growth factors in the final concentration used[2].

Post-Procedure[edit | edit source]

Depending on the location of the PRP injection, physicians may have a specific post-procedure protocol depending on the location and type of injection. This can include periods of immobilization or altered weight bearing status before gradual progression back to function and/or sport. Post-procedure protocols have not been addressed in the available research.

Patients may be recommended to stop taking NSAIDS in the initial post-procedure healing phase to not hinder the pro-inflammatory goal of PRP injections.[5]

Resources

[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Everts P, Onishi K, Jayaram P, Lana JF, Mautner K. Platelet-Rich Plasma: New Performance Understandings and Therapeutic Considerations in 2020. Int J Mol Sci. 2020 Oct 21;21(20):7794.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Samadi P, Sheykhhasan M, Khoshinani HM. The Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma in Aesthetic and Regenerative Medicine: A Comprehensive Review. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2019 Jun;43(3):803-814.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Belk JW, Kraeutler MJ, Houck DA, Goodrich JA, Dragoo JL, McCarty EC. Platelet-Rich Plasma Versus Hyaluronic Acid for Knee Osteoarthritis: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Sports Med. 2021 Jan;49(1):249-260.

- ↑ Liu CJ, Yu KL, Bai JB, Tian DH, Liu GL. Platelet-rich plasma injection for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinopathy: A meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Apr;98(16):e15278.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Wu PI, Diaz R, Borg-Stein J. Platelet-Rich Plasma. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2016 Nov;27(4):825-853.

- ↑ Mlynarek RA, Kuhn AW, Bedi A. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) in Orthopedic Sports Medicine. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2016 Jul-Aug;45(5):290-326.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins Medicine. Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) Injections | Q&A. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NxW4dPcNRBM [last accessed 13/2/2022]