Breast Cancer

Top Contributors - Adam El-Sayed, Kim Jackson, Lucinda hampton, Vidya Acharya, Admin, Chee Wee Tan, Ilona Malkauskaite, Candace Goh, Manisha Shrestha and 127.0.0.1

Introduction[edit | edit source]

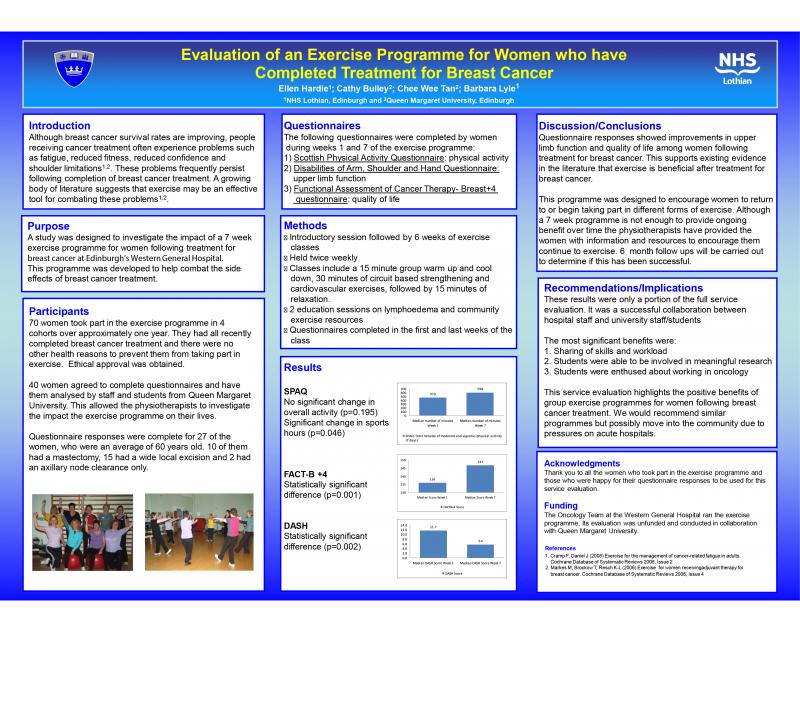

There is a growing evidence base reporting the physiological and psychological benefits of physiotherapy as a safe and effective adjunct to breast cancer treatment [1]. With survival rates at an all time high the National Cancer Survivorship Initiative (NCSI) Vision (Department of Health) has stated that health professionals must now focus on meeting the unique needs of breast cancer survivors and improve accessibility to specialist services, including physiotherapy. Services ideally will be able to deliver physiotherapy interventions to better empower patients in the management of their symptoms, side-effects of treatment or recovery from surgery. Recent specialist breast care physiotherapy services are now being developed so that physiotherapists are prepared to deliver a high standard of care through such initiatives.

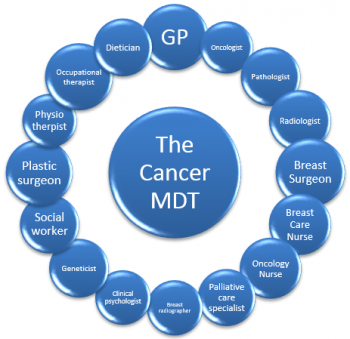

Breast cancer patients face an array of problems and have specific needs which must be addressed in order to prevent long term functional limitations and disability. The physiological and psychological benefits from physiotherapy for breast cancer patients are well documented, with improvements observed in terms of morbidity, mortality and importantly, quality of life [2]. Thus, the potential role for physiotherapists in this area is clear to see and highlights the importance of training for physiotherapists to develop the skills required to meet patient needs and maximise their contribution to the MDT.

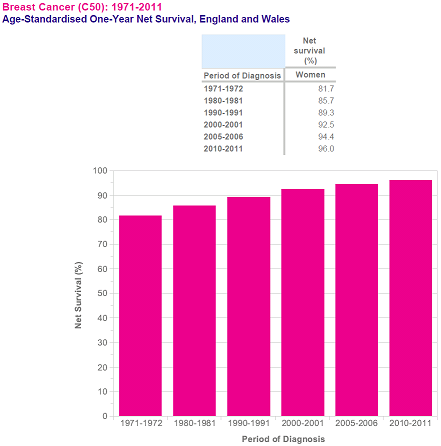

Breast Cancer Prevalence and Survival Rates[edit | edit source]

Breast cancer is the most common cancer in the UK. An estimated 1 in 8 women in the UK will develop breast cancer in their lifetime and the incidence of breast cancer has risen by 7% in the last 10 years. In part this may reflect the effectiveness of NHS screening programs (16,500 cases were detected in 2009 alone) however increasing incidence is also a global issue with an estimated 1.68 million diagnoses made in 2012 worldwide [3]. Survival rates are also increasing. Today, more women are surviving breast cancer than ever before. Most recent figures reported by Information Services Division Scotland showed that high percentages of women diagnosed with breast cancer in Scotland between 2003 and 2007 were surviving 1 year (93.8%) and 5 years post diagnosis (81.4%). Similar trends have been reported for the rest of the UK [3].

Pathophysiology of Cancer Cells[edit | edit source]

Cancer cells differ from normal cells in the disregulation of cell division and growth. As a normal cell develops into a neoplastic state, the cell undergoes changes in six forms.

- Sustaining proliferation: cancer cells change growth promoting signals by altering pro-ocogenes to oncogenes thereby disrupting the homeostasis of cell structure and function. This results in sustained chronic proliferation without external stimulation.

- Evading growth suppressors: by overcoming the effects of tumour suppressing genes that prevent cell growth, tumours are able to grow uninhibited.

- Resisting cell death (apoptosis): the spread of cancer cells may be escalated due to a rise in gene mutations leading to ineffective programmed cell death.

- Enabling replicative immortality: in normal cells telomere shortening causes cell division to stop. Cancer cells enable widespread self-replication using the enzyme telomerase to prevent telomere shortening, allowing repeated cell division without DNA shortening.

- Sustained angiogenesis: as in normal cells angiogenesis allows cancer cells to acquire nutrients and oxygen with the elimination of metabolic waste and carbon dioxide. Subsequently a vascular system is created to maintain tumour growth and metastasis.

- Activating invasion and metastasis: the spread of cancer cells is made possible when cells break free from the primary tumour and enter the blood and lymphatic vessels. Subsequently the development of a second tumour may occur in different site of the body to the primary tumour [4].

Pathophysiology in Breast Cancer[edit | edit source]

- Non-invasive breast cancers are present in the ducts or lobules.

- Invasive cancers are found in the surrounding breast tissue.

- Cell Grade: Cells are graded in a system where grade 1 cancer cells present slightly differently to normal cells, progressing to grade 3 cancer cells which demonstrate major differences to a normal cells.

- Tumour Necrosis: tumour necrosis may be present in aggressive forms of breast cancer where cells are seen to grow at a rapid rate.

- This is often a sign of a rapidly growing aggressive form of breast cancer.

- Vascular or Lymphatic Invasion: - these types of invasion describe whether or not cancerous cells are evident in the vascular and lymphatic vessels supplying the breast tissue.

- Hormone Receptor Status: - Hormone receptor status determines if hormone therapy would be appropriate.

- HER2 Status: - HER2 is a gene that when dysfunctional can play a role in the development of breast cancer. Breast cancers that are HER2 positive tend to grow faster and are more likely to spread that those that are HER2 negative.

Musculoskeletal Problems Experienced in Breast Cancer Patients[edit | edit source]

The breast cancer patient can also be susceptible to the development of musculoskeletal problems, the same as the general population. One common problem is symptomatic rotator cuff disease, which can be brought on through intrinsic factors such as age related physiological changes to the tendons, or through extrinsic factors brought on from cancer treatment such as lymphedema as well as shoulder girdle resting alignment. Tension overload on the rotator cuff tendons may be increased secondary to increased volume and weight of the effected limb with the presence of lymphedema. Due to pain, or fear of movement, for example, the breast cancer patient may adapt to a new resting position for their shoulder, and may tend to avoid using the limb, resulting in shortening of the muscles, and tightening of the joint capsule [5]. Moreover, patients tend to adapt a flexed and protective posture following surgery, further increasing the likelihood of muscle shortening. Pectoralis major is commonly effected. Tightness of these muscles tend to lead to a pull on the scapula, causing it to become protracted and depressed, leading to scapular winging, as well as shoulder impingement [6].

Post Mastectomy Pain Syndrome (PMPS)[edit | edit source]

Pain which lasts longer than what is usually expected following various breast cancer surgery types. Generally neuropathic in nature, and can be due but not limited to:

- Brachial nerve damage, *Intra-operative compromise of cutaneous innervating,

- Neuroma formation,

- Fibrotic entrapment. Patients often report neurological symptoms such as numbness or pins and needles, stabbing and burning pain to the same side as surgery in or around the surgical sites.

These symptoms can be exacerbated through a lack of pacing, or by lying on the side of surgery. Therefore, patient education, soft tissue massage, and other desensitising techniques are essential [6]. Other common problems include:

- Subacromial Impingement Syndrome.

- Adhesive Capsulitis (frozen shoulder) – idiopathic or traumatic (post-surgery).

- Rotator Cuff pathology (e.g Symptomatic Rotator Cuff Disease)

- Myofascial Dysfunction Lateral epicondylitis.

- Scapular winging secondary to damage of long thoracic nerve during surgery.

- Pain

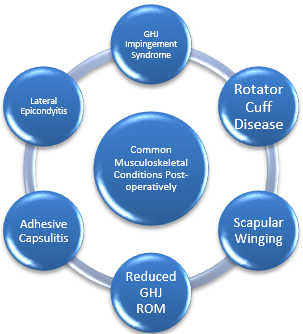

Associated Neuromusculoskeletal Conditions Post Treatment[edit | edit source]

Neuromusculoskeletal conditions are common following surgery, some of which are illustrated in figure 1.4. Treatment protocols shall not be discussed, and the reader should refer to the basic principles of rehabilitation of musculoskeletal conditions. In light of this, it is important to briefly discuss a few points to consider.

- Depending on the type of surgery that the patient needs to undertake, radiotherapy may be necessary following surgery.

- A typical radiotherapy session will require the patient to position the treated arm to 90° flexion and abduction, as well as maximal external rotation, for up to 30 minutes [7].

- Shoulder mobility is commonly affected post-surgery [8]; [9]; [10] so it is vital that physiotherapy aims to restore this to improve patient functional ability and to be able to place the shoulder in the required positions for radiotherapy.

- Active, active assisted, and passive ROM exercises for the shoulder girdle are therefore good practice. Physiotherapy should aim to restore full shoulder ROM as well as minimising associated upper extremity morbidity [11].

- Manual therapy techniques with the aim of further increasing available ROM have been shown to not be of any significant benefit when used in conjunction with active upper limb exercises [12].

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Due to the complex nature of cancer and the treatment process that accompanies the condition, the condition requires expert input across of wide range of health professionals [13]. In light of this, there is potential for miscommunication on occasion. A solid MDT should improve communication between health professionals, which should optimize the treatment process for the breast cancer patient [14].

Surgery[edit | edit source]

Surgery is performed in order to remove as many cancer cells as possible, to investigate where the cancer cells have spread to, for reconstruction, or to reduce symptoms in the later stages of cancer. Below is a brief outline of the common procedures. Selection criteria for surgery:

- The size of the tumour present and the location

- Whether or not the cancer cells have spread

- Breast size

- Personal wishes of the patient

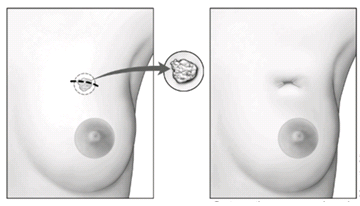

Excisional Breast Biopsy (Lumpectomy)[edit | edit source]

- A lumpectomy, otherwise known as a wide local excision, tends to be used in early stage cancer or when the tumour is of small size.

- The surgeon will remove the cancer cells, as well as some of the healthy tissue which surrounds the affected area. *This can be done with general or local anaesthetic, with the aim of determining the mass of the tumour and to rule out any carcinoma.

- Due to the conserving nature of this procedure, it is one that is favoured by the breast cancer population, and has even been shown to have no significant difference in survival rate when compared with a mastectomy [15].

- The excised tumour is examined further for cancerous cells, if which are found around the edges, may lead to further surgery or mastectomy

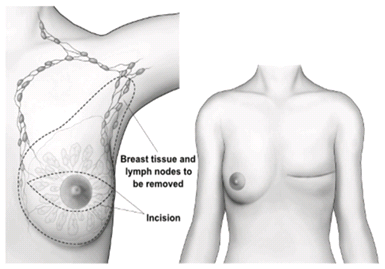

Subcutaneous Mastectomy (Complete Mastectomy)[edit | edit source]

- This procedure results in complete removal of the breast tissue only (>99% of breast tissue), where a carcinoma is in situ.

- When the size of the tumour is large in proportion to the rest of the breast tissue, or is wide spread, a mastectomy is performed.

- As previously mentioned, a mastectomy may be performed if a lumpectomy is unsuccessful in the removal of all cancer cells.

- It may also be performed if cancer cells were to recur following other treatments such as radiotherapy.

*Occasionally, complete removal of the pectoralis muscle group can occur if cancer cells were to spread into the musculature.

Modified Radical Mastectomy (MRM)[edit | edit source]

- MRM indicated where:

- Tumour location, size, and presence of multiple cancer cells in the breast tissue.

- Where radiotherapy is contraindicated.

- Dissection and removal of the lymph nodes within the axilla occurs. The likeliness of morbidity in the arm [16] is increased and can even lead to permanent lymphedema depending on the amount of lymph nodes removed.

- Dissection sites:

- Lateral edge of the sternum, clavicle, within latissimus dorsi, rectus sheath

- Breast tissue’s usually dissected from the pectoralis muscle; occasionally compromised.

- Strain injuries to the brachial plexus are common, but usually resolve over time.

- Injuries to the long thoracic nerve are quite common following this particular surgery.

- Loss of range of motion (ROM) in the glenohumeral joint (GHJ) is quite common following this procedure, physiotherapy has been shown to manage this [16].

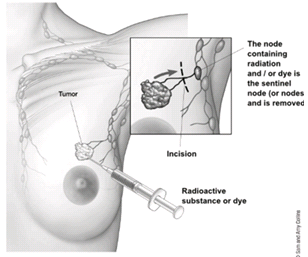

Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy[edit | edit source]

- Radioactive dye is injected into the breast tissue as a further diagnostic measure to evaluate whether the cancer cells have entered the lymph nodes or not.

- Once identified, the lymph nodes containing the cancer cells, i.e. the sentinel lymph nodes, are then removed surgically.

Radiotherapy[edit | edit source]

- Almost half of cancer patients will use radiotherapy over the course of their cancer treatment.

- Designed to eliminate cancer cells through the application of high-radiation energy to the affected site. *One the main causes of arm pain in cancer patients [17]

- Risk factor for breast cancer related lymphedema.

- It is often used in with and separately to chemotherapy

- Radiotherapy can be used as a neoadjuvant treatment, or as an adjuvant treatment.

- The main muscles in the line of radiotherapy are the pectoralis muscles, latissimus dorsi, and serratus anterior. Although radiotherapy is a successful tool in the treatment of cancer, there are quite a few side effects, which may last days to years. Skin irritation, for example, is one of the most common side effects [18], with patients experiencing erythema, skin peeling, and even necrosis [19]. As previously mentioned, the direct contact radiotherapy has on the muscles pectoralis major, latissimus dorsi, and serratus anterior, can lead to damage of these healthy tissues, causing pain and inflammation. As in relation to the post-surgical posture which was previously mentioned, patients can tend to adapt a protective posture due to increased sensitivity and fear of movement, again predisposing to contractures and a decreased ROM [6].

Radiotherapy Side Effects[edit | edit source]

Radiation Induced Fibrosis (RIF)[edit | edit source]

RIF is common following high dose radiotherapy which causes secondary damage to the normal tissues which surround the cancer sites. 45% of patients report RIF related breast pain, which in turn negatively effects the patients’ quality of life [6].

Chemotherapy[edit | edit source]

- Chemotherapy is a systemic therapy with the aim of killing the dividing cancer cells present in the tissue through the use of a single of various different drugs.

- Adjuvant chemotherapy prolongs disease free and overall survival in patients with early breast cancer [20], and is primarily used in the earlier stages of the disease.

- Used if cancer cells have spread from the original site, or if there is risk that it will spread.

- It can be used as a curative therapy, as well as in conjunction with radiotherapy [21], or can be used to help relieve some symptoms present in the later stages of cancer.

- Treatment processes usually last up to 6 months.

- Chemotherapy may involve the use of a single drug, or a combination of different drugs. A full list of drugs used in cancer treatment, along with their side effects, can be located here.

The benefit of chemotherapy is evident, in contrast, cardiac side effects are also quite common amongst patients treated with chemotherapy. Depending on the drug used, various cardiac side effects can develop, such as:

- Myocardial ischemia

- Left ventricle dysfunction Although these issues cannot be directly influenced through physiotherapy, knowledge of the potential presence of these conditions is vital [22]. Chemotherapy induced cardiac toxicity is an ever growing problem, with research stating patients receiving chemotherapy are placed at Stage A heart failure, increasing the risk of cardiac dysfunction in the future [23], with the chance of heart failure possibly being higher than the chance of cancer recurrence [24]

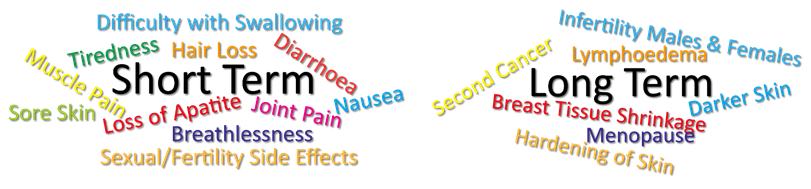

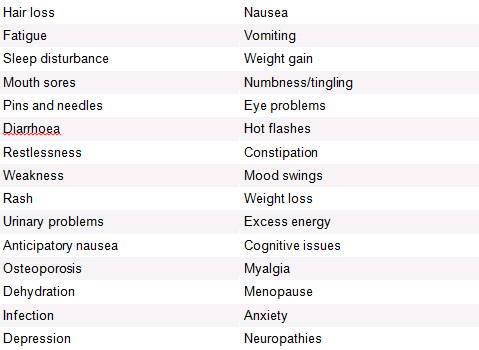

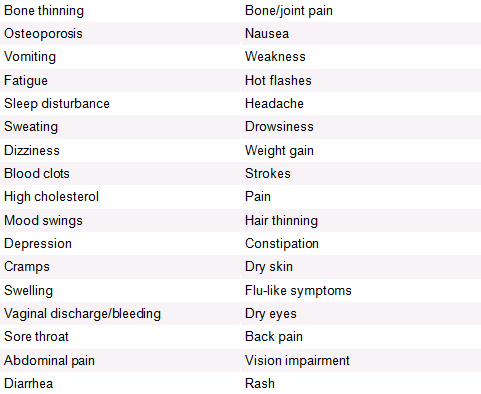

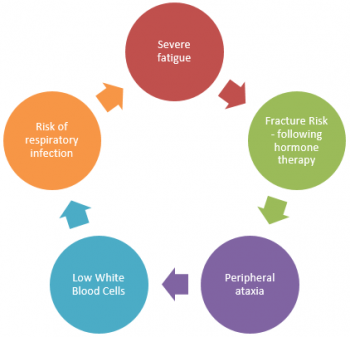

Chemotherapy Side Effects[edit | edit source]

Hormone Therapy[edit | edit source]

Hormone therapy will only work in oestrogen receptor positive cancers. Oestrogen receptor positive cancer cells contain a hormone receptor which enables the binding of oestrogen onto the cancer cells, enabling further growth of the cancer. These same receptors are present on normal and healthy breast tissue cells. Hormone therapy aims to:

- To limit growth of the spreading hormone positive cancer cells

- To prevent recurrence

- To decrease the risk of developing hormone positive cancers in the future Aromatase inhibitors are drugs used in hormone therapy. Aromatase is involved in the biosynthesis of oestrogen from androgens located in various tissues throughout the body, primarily adipose tissue in menopausal women. Aromatase inhibitors also lead to a loss of bone density, further predisposing the breast cancer patient to osteoporosis. Therefore, the role of the physiotherapist in hormone therapy should be advice and education, accompanied with cardiovascular and light resistance training with the aim of decreasing chance of obesity and lowering the stress on the potentially weakened bones [6].

Hormone Therapy Side Effects[edit | edit source]

Like with chemotherapy, there are many different medications used in hormone therapy, each of which have different side effects.

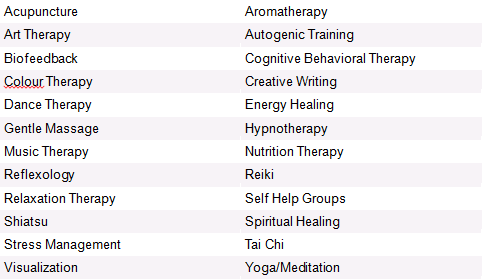

Complimentary Therapies[edit | edit source]

There are many therapies which could possibly be discussed with a breast cancer patient, with the aim of helping them cope through their rehabilitation, any negative symptoms, and to promote their general well-being.

Musculoskeletal Physiotherapy Interventions Post Surgery[edit | edit source]

A physiotherapists treatment plan should include:

- Motion exercises to improve tissue extensibility and facilitate normal movement patterns.

- Myofascial release for enhancing mobility and enhancing tissue extensibility. [25] [26] [5] [6]

Reduced Range of Motion and Lymphedema[edit | edit source]

The two most common complications that are evident in breast cancer patients are restricted arm motion and lymphedema. These result in the occurrence of pain at the place of operation and muscle spasms are quite common. It is very important that early rehabilitation is implemented to promote functional movement to the patient’s previous level of activity. Subsequent to operation arm mobilisations are implemented first or second day post-op. Mobilisations are performed using joint rotations to tolerance but abduction and flexion are limited to 40°. At day 4 post-op flexion and abduction are gradually increased to 45°, this can be increased furthermore by 10-15° per day dependent on the patient’s pain tolerance. The technique performed by holding the patients arm in 45° flexion or abduction until the drains are removed. Secondary lymphedema is a common occurrence in the breast cancer population following surgery and has a long term negative effect on patient quality of life. Risk factors that are prevalent in the breast cancer population are age, obesity and the growing survival rate. The growing risk factors make secondary lymphedema a challenging complication in the breast cancer population.

Physiotherapy Interventions for Lymphedema[edit | edit source]

Complex decongestive physiotherapy for lymphedema[edit | edit source]

This is a treatment that incorporates skin hygiene, manual lymph drainage, bandaging, exercises and support garments. Manual lymphoedema drainage is a massage technique that involves the skin surface only. This follows the anatomical lymphatic pathway. Generally the manual lymph drainage technique will begin centrally in the neck and trunk to alleviate any lymphedema in the main lymphatic pathway, so that drainage in the arm is facilitated. Complex decongestive physiotherapy has been suggested as the primary treatment for breast cancer patients. This treatment includes skin care, exercises, compression and manual lymphedema treatment. Complex decongestive physiotherapy has shown to be an effective method for the treatment of lymphedema when standard elastic compression has been unsuccessful. One study showed consistent results of the reduction in volume of the effected extremity in 95% of 400 patients. A follow-up showed that these therapeutic results were maintained at 3 years.

Elevation[edit | edit source]

Elevation has been described as a non-effective treatment when performed solely in breast cancer treatment for arm related oedema. Elevation is commonly used together with other treatments to provide the most effective treatment. Most commonly in breast cancer treatment a multidisciplinary approach is taken where the patient will undergo massage and exercise. A specific technique of massage is commonly implemented named manual lymphatic drainage. Manual lymphatic drainage is a type of massage used to mobilise oedema fluid from distal to proximal areas and from areas of stasis to healthy lymphatics.

Compression[edit | edit source]

One form of lymphedema treatment which has proved most effective in the treatment of breast cancer patients is the use of standard elastic compression garments. Studies have shown significant improvements using simple elastic compression treatment for lymphedema, where 34% of patients showed a substantial reduction in arm oedema at 2 months and 39% of patients at 6 months. This conclusion was also seen in patients older than 65 years old [27].

Physiotherapy to prevent secondary lymphedema arising[edit | edit source]

- Stretching for muscles of the shoulder: Levator scapulae; upper trapezius; pectoralis major and the medial and lateral rotators of the shoulder

- Progressive active and active assisted shoulder exercises.

- Functional exercise activities.

- Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation exercises.

Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

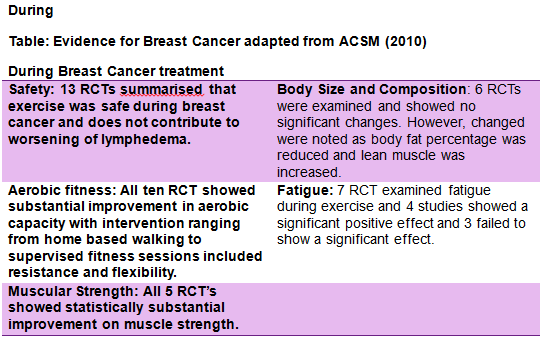

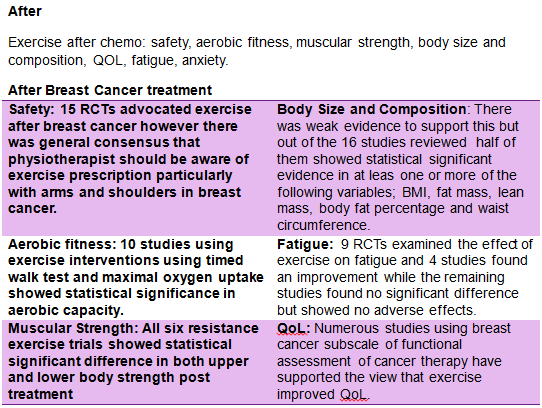

Exercise is increasingly being implemented as a therapeutic tool in patients with breast cancer [28]. In recent times it has become clear that exercise has a central role to play in controlling and preventing chronic illness. However, statistically breast cancer survivors have a very low compliant rate and despite the renowned benefits of exercise, 22% Canadian cancer survivors report being inactive [29]. Physical exercise has shown to be a suitable adjunct therapy to battle long term chronic conditions and has been successful in reducing mortality and improving overall quality of life. There is substantial evidence to support the benefits of exercise in breast cancer in both during and after chemotherapy. Research has shown that physical activity and exercise is effective in improving QoL, cardiorespiratory fitness, physical functioning in breast cancer patients and survivors [30]. These studies where compared with similar studies and analysed in separate components such as safety, aerobic fitness, muscular strength, body size and composition, QOL, fatigue, anxiety. Physical exercise has shown to be a suitable adjunct therapy to battle long term chronic conditions and has been successful in reducing mortality and improving overall quality of life. A review of the current literature by Corneya [28] carried out an overview of research on the effect of exercise on cancer. Twelve studies met the inclusion criteria and showed statistically significantly beneficial results in the effects of exercise during breast cancer. More so, the studies demonstrated benefits exercise capacity, body weight and overall quality of life. The ACSM [30] discussed guidelines for cancer survivors and analysed studies during and after breast cancer separately. The ACSM[30] compared studies during breast cancer using the following headings; safety, aerobic fitness, muscular strength, body size and composition, QOL, fatigue, anxiety.

Precautions[edit | edit source]

There is a general assumption that upper limb exercises could be harmful to patients who had axillary nodes removed or radiation the axilla, however the latest research does not support this view.

When performing exercise for post surgical populations the SEWS chart should be monitored regularly for early warning signs. If the patient is feeling fatigued or anaemic exercise should be delayed.

Exercise Prescription[edit | edit source]

The ACSM guideline suggests that an overall volume of 150 mins of moderate-intensity exercise or 75 min of vigorous intensity exercise. Resistance exercise should be performed 2-3 times weekly with exercises including the major muscle groups. However, with patients undergoing cancer treatment the key is to avoid inactivity and the patient should remain as active at their ability and condition allows them.

FITT Guidelines[edit | edit source]

There is a huge gap at present in the research governing exercises prescription and its translation to the real world and community settings. As discussed earlier exercise compliance post cancer is very low and a qualitative study by Miedema [31] stated numerous factors for this such as lack of availability of services, travel issues, cost and personal reasons as family responsibilities and fatigue. Physiotherapist should be aware of the barriers to exercise compliance in this specific population (See #Barriers ).

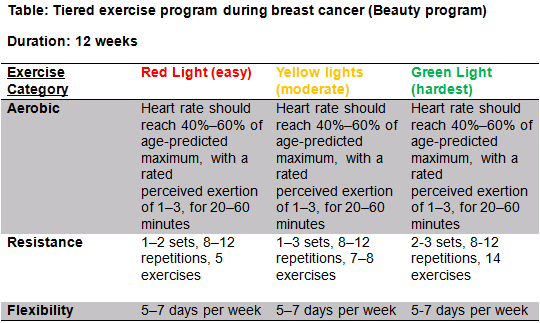

The beauty program aims to counteract key concerns associated with breast cancer patients such as fatigue, reduced QoL, social anxiety and physical conditioning. Considering there is huge physiological benefits as well major psychological benefits it is important that the physiotherapist promotes the benefits of exercise immediately post-surgery and ensures that the exercise program is assessable at home or in the community and is specific to the individual. All exercise programs should be designed with F.I.T.T principles during and after breast cancer. A recent study by Leach [32] designed an exercise program called BEAUTY (The breast cancer patient engaging in activity and undergoing treatment program).The beauty program aims to bridge the gap between the body of evidence supporting the role of exercise in breast cancer and implementing this in a real world setting.

BEAUTY:

Patients were assessed by exercise physiologist before undergoing exercise treatment and underwent a variety of tests to get measure of baseline fitness and also filled out questionnaires relating to exercise and medical history, fatigue, QoL and depressive symptoms.

FITT Principle After Breast Cancer[edit | edit source]

- Warm up: 5-10 minutes to raise heart rate

- Aerobic Exercise: Frequency:

- 3 x 5 times per week **Intensity: 50-70% of max. heart rate

- Type: walking cycling aerobic activity

- Time: 30 minutes maintaining as a long term routine

- Resistance Training: Frequency:

- 2/3 times a week

- Intensity: 12/15 reps of 60 % of 1RM

- Type: Supervised resistance program of major muscle groups

- Time: 6 weeks

Barriers, Motivators and Myths and Physical Activity[edit | edit source]

- Breast cancer patients report more barriers to exercise than other cancer groups [33].

- The barriers are having a clear impact on activity participation.

- Only 30-47% of cancer survivors are undertaking the physical activity guidelines of 30 minutes of moderate intensity activity per day [34]

- Understanding the barriers can help physiotherapists in making services more accessible to breast cancer survivors and encourage participation.

Myths[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists have an important role to play as educators in dispelling the myths and presenting patients with evidence to reassure them that exercise will not be harmful. Survivors often report concerns about the safety and benefits of exercise for their condition, however it is important to note that exercise both during and after cancer treatment has no known significantly negative effects [28] [35] [36].

Barriers[edit | edit source]

The main themes identified from interviews with survivors are physical, environmental and psychosocial [37]. Top 10 patient reported barriers to exercise [38]

- Concerns about their illness and other health problems

- Joint stiffness

- Fatigue

- Pain

- Lack of motivation

- Weather

- Lack of facilities

- Weakness

- Lack of interest

- Fear

Psychological Barriers[edit | edit source]

Psychological barriers identified from a large qualitative study by Hefferon et al [39] included:

- Lack of motivation

- Fear of injury

- Fear of lymphodema

- Dislike of gym environment

- lLck of privacy

“I just couldn’t … I had no energy to do anything. I could hardly drag one leg after the other...” - Anon [39]

"I had my breast off, I had to go through a year later for another operation … you’re all kind of sore and tense [...] plus the fact that the chemotherapy affected the nerve in my feet, so I didn’t have the strength ... I didn’t have the feeling in my feet.” - Anon (Hefferon et al. 2013)

Low mood and depression are commonly reported by patients and understandably make motivation to exercise extremely difficult.

“I feel sad. Even when I wanted to go out.…With other kind of physical sickness it’s ok but with cancer… so difficult to get myself out of this…” -Anon [40]

Physical Barriers[edit | edit source]

The following may contribute to negative feelings towards exercise participation [41]:

- Cancer treatment side-effects including weakness, loss of shoulder movement, musculoskeletal pain, neuropathy, weight gain and breast cancer related lymphoedema

- Post surgery complications e.g numbness, shoulder stiffness, lymphodema [42]

- Cancer or age related aches and pains

- More than half of patients report fatigue and 68% of participants in one study reported not having been told how to manage it [43]

Breast Cancer Related Lymphodema (BCRL)[edit | edit source]

BCRL manifests as chronic oedema of the upper limb and trunk in response to damaged axilliary lymph nodes as a result of surgery. As a result patients experience pain, a heavy feeling in the arm, psychological distress and self image concerns as well as increased risk of infection [44] [45]. Occurrence differs for populations of survivors, with prevalence being reported as anything between 2 and 83% [41]. In the past it was common belief that exercise could exacerbate BCRL and as such women were discouraged from exercises such as weight training [46], [41]. Research inspired by McKenzie et al's [47] “Abreast in a Boat – a race against breast cancer” has since refuted this, leading to a new culture of exercise promotion in breast cancer survivors.

Dragon Boat:

The subject is still a source of confusion and concern for many survivors. At present it cannot be said for certain that exercise will not increase occurrence of BCRL, however recent research does suggest that exercise does not cause clinically harmful effects related to BCRL [48],[41]. Encouragingly, studies on weight training and BCLR found no significant link between exercise and increased oedema when the exercises were closely supervised and progressed gradually [49] [50]. Furthermore, the implementation of early physiotherapy may lower or eliminate the occurrence of secondary lymphoedema in breast cancer patients who have undergone surgery.

Psychosocial Barriers[edit | edit source]

Patients may have Psychosocial barriers to exercise such as time constraints, issues with return to work, family commitments, as well as the facilities and environments available for exercise participation. Cancer incidence is high in women aged between 40-50. Many in this age group are active, working mothers with families and many responsibilities who devote much of their time to family and child care. We must also consider the time demands that come with multiple hospital appointments during and after treatment. As therapists we must therefore consider where and when the patient can exercise, what alternatives and comprises can be made as an alternative to gym based exercise.

Barriers During Versus After Treatment[edit | edit source]

Recently diagnosed women expressed more negative feelings towards physical activity than those after treatment, and may be less aware of the benefits of activity. Those who were currently undergoing treatment state that the need to conserve energy and fear of infection were of great concern to them when deciding to exercise. [51].

Motivators[edit | edit source]

Social support is commonly reported as a motivator for survivors. Group programs are said to provide a supportive, safe environment [52], which therapists should keep in mind when offering exercise advice.

“I think it is good to find a group of people and do together …because being alone is very lonely and harder to sustain the physical activity.’-Anon [52]

Common motivators reported include weight loss, health benefits, increased energy, body image and social support [37]. One patient stated the importance of exercise facilitators being understanding and caring.

“...the instructor that I had was very caring. I couldn’t keep up through the whole class so she would come up to me and say: ‘Are you doing ok?’ I think that helped me. It made me feel, not that people felt sorry for me, but were concerned that I was okay.” Anon [37]

Top 10 patient reported motivators for exercise [38]

- Fun

- Variety of exercises

- Gradual progression

- Flexible

- Personal goal setting

- Good music

- Individually tailored

- Feedback given

- Oncologist approval

- GP approval

Psychological Issues[edit | edit source]

Breast cancer diagnosis is a traumatic experience affecting not only the patient but all involved in the patient’s life. Cancer patients go through an emotional journey that affects their psychological wellbeing and mental health. It is therefore important that alongside the physiological treatment, care is taken of the patient’s emotional wellbeing to protect their long-term quality of life. The psychological issues surrounding the breast cancer patients, their carers and health workers, should be addressed at an early stage by ensuring that support and guidance is available to patients and others in need.

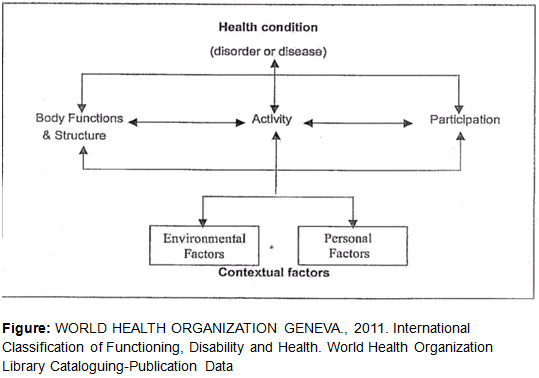

Biopsychosocial Model[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organization defines the biopsychosocial model as:

“attempts to achieve a synthesis, in order to provide a coherent view of different perspectives of health from a biological, individual and social perspective” [53]

The goal of the ICF classification is to provide a unified language and framework to describe health and health-related states. The ICF has two parts:

- Functioning and Disability - includes body function and structures, and activities and participation. #Contextual Factors - includes environmental factors, as well as personal factors. These represent the individual’s background and lifestyle. The environmental factors are the physical, social and attitudinal environment in which the person lives. They are external factors and can either be positive or negative influences on the individual’s performance as a member of society, on the individual’s ability to complete tasks, or on the individual’s body function and structure. (see #Barriers.2C_motivators_and_myths_behind_physical_activity_in_breast_cancer_survivors )

Environmental Factors[edit | edit source]

These include the immediate environment e.g home, workplace or school. Other individuals who whom they have direct contact are also included. The second focus is the way the environmental factors relate to functioning and disability. Different environments may produce different impacts on the same individual with a given health condition. An environment with barriers will restrict an individual’s performance in society, while an environment that is more facilitating may enhance their performance. (see #Barriers.2C_motivators_and_myths_behind_physical_activity_in_breast_cancer_survivors )

Personal Factors[edit | edit source]

This includes important aspects of the individual not directly related to their health status. They include things such as gender, race, age, other health conditions, fitness, lifestyle, habits, upbringing, coping styles, social background, education, profession, past and current experience, overall behavior pattern and character style, individual psychological assets and other characteristics, all or which may play a role in any level of disability. The ICF is based on the integration of the functioning and disability model with contextual factors. This is in an attempt to capture the integration of various perspectives of functioning. Thus, it attempts to achieve a synthesis, in order to provide a coherent view of different perspectives of health from a biological, individual and social perspective. As such the biopsychosocial model provides a framework to assist healthcare professionals in “expanding their repertoire of anxiety management strategies and empowering patients to learn self-healing modalities that interrupt major anxiety pathways, thereby contributing to secondary prevention.” [54] Working through the biopsychosocial model of health, it is clear that in our role as physiotherapists we need to address more than just patient’s physical needs. All the needs and concerns need to be treated.

The advancement of science and medical technology has brought a decrease in physical deformity from today’s surgical treatments. said, contemporary breast cancer treatments are becoming more complex and require a longer period of time. This is due to an increase in the available information and due to more opportunities of information and choices given to patients detailing their cancer diagnosis and prognosis and sharing the decision-making process regarding clinical intervention and treatment.

Psychological Aspects[edit | edit source]

Amongst the psychological aspects impacting on the physiological system are depression, self-esteem, fear of recurrence, changes in body image and sexuality, as well as physical toxicities that result from adjuvant therapy. A research carried out by Ganz, P.A. (2008) addresses the importance of identifying the psychological and social concerns of breast cancer patients in the clinical setting, and it assists patients in obtaining appropriate psychosocial services. Further information from this paper can be obtained by following this link. Robotin M. et al [55] discuss the impact that the psychological concerns have on cancer survivors and state that:

“other issues such as difficulties in decision-making and social isolation may emerge months or years after treatment has finished”

This implies the nature of the survivorship – a dynamic experience which changes over time – and the importance of the life style and social support to cancer survivors. Despite recent advances in the treatment of cancer, people have a universal dread of cancer and in most cases the disease remains highly stigmatised.

Strategies for Dealing With Psychological Issues[edit | edit source]

The following are some of the key strategies we should take into account when addressing the psychological problems that may arise from breast cancer diagnosis:

Patient-Centred verbal communication is key and all staff should seek to develop their skills in this aspect as part of the continuous professional development. All forms of communication should be patient-centred. Each health professional should act pro-actively to develop good working relationships with key relevant players and patients, including MDTs. To address and overcome these psychological issues it is imperative to have effective communication tools that can be used and accessed by all those involved in the patient health journey.

Physiotherapy - Long Term Management[edit | edit source]

When exploring and defining strategies for long-term physiotherapy management of patients with breast cancer, barriers, motivators and myths behind physical activity in breast cancer survivors should also be addressed.

The role of a physiotherapist is to promote a healthy life style including physical activity and proper nutrition. As highlighted previously, exercise interventions are being used and incorporated into treatment however much more research is needed to implement it on a higher standers of care level. Continuation of exercise can continue to foster motivation in patients, provide a support group for patients, enable social and psychological wellbeing. Most of all it can improve patients quality of life. It allows patients to have some control over their lives, stability and routine. It allows them to regain themselves and return to being active in a community [56].

Education[edit | edit source]

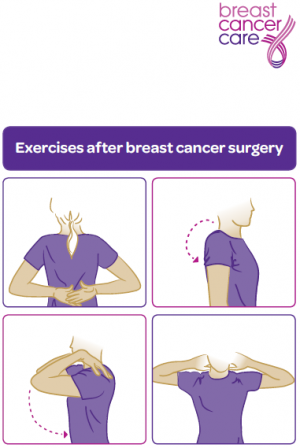

Education plays a vital role in patient centred care and clinician evidence base practice. There is clear efficacy for the use of education as has been highlighted throughout this resource. Breast Cancer Care developed a resource for exrcise after breast cancer surgery and is readily available here. McMillan Cancer Support also have another useful resource targeted towards marketing activitiy entitled Move More

The ACPOHE state that education of the patient is a key component of the physiotherapists role. ACPOHE recommend promotion of physical activity, independence and self-management as greatly important for successful rehabilitation outcomes. In reference to the biopsychosocial model of health, it is clear that physiotherapists have a duty to address more than just the patient’s physical problems. All patient needs and concerns need to be treated, an issue which was highlighted by Karen Middleton (CSP Chief Executive) in a speech at the Physiotherapy UK 2014 conference which may be viewed here.

“...physios can reverse injury, enable people to live with long-term conditions, integrate health and social care and help people back into work...we’re very good value”

Life After Cancer[edit | edit source]

Life after breast cancer treatment means returning to some familiar things and also making some new choices. The end of treatment does not mark the end of the journey with breast cancer. The patient embarks to adjusting to life as a breast cancer survivor and in many way will have a life that is in some ways very different from the life before. These changes include relationships to eating habits and exercise. How do you fight lingering fatigue? What should you eat to help prevent a breast cancer recurrence? Will you ever have a regular sex life again? These are just a few of the questions that may nag at the patient as they make the transition from breast cancer treatment to breast cancer survival. The patient’s body has been through an enormous assault and recovery is a huge thing – the patient cannot bounce back right away. Two of the more frustrating and troubling side effects women face after treatment are fatigue resulting from chemotherapy and/or the accumulated effects of other treatments, and a phenomenon some women have dubbed "chemobrain" -- mental changes such as memory deficits and the inability to focus.

Patients should be advised to make sure that their family and work colleagues understand that just because treatment is over, that doesn't mean that she is going to be able to jump right back into running the office, coaching, and travelling to conferences a week out of every month. The issue of returning to work shortly after the treatment, has been addressed by many organisations, amongst them cancer societies such as the American Cancer Society, who advise that returning to work may help maintain your sense of who you are and how you fit in. However, the return to work should be graded and the possible options should be explored with the employer, like flexi-time, job sharing, or working from home.

Options like these may help the patient ease her mind and body back into the demands of her job. The Association of Chartered Physiotherapists in Occupational Health and Ergonomics referred to their role as:

“Physiotherapists in Occupational Health use their professional knowledge and skills, together with skills for interaction and decision-making/problem-solving to assess the occupational health needs of the workforce, and to design and deliver personalised advice and interventions that maximise an individual’s performance at work”. (ACPOHE 2013)

Vocational Rehabilitation physiotherapists are involved in the early treatment and timely application of appropriate treatment and advice. This allows patients to remain active, suitably return to work following injury, and remain at work upon return [57]. The physiotherapist should develop personalised interventions for each individual patient and duties include assessment of workers abilities, job and task analysis for each individual patient.

The physiotherapist can assist the patient with her plans to return to work by carrying out assessments on the physical capabilities of the patient in relation to the work place. A work place assessment will also benefit the achievement of this goal. Following the workplace assessment, an adjustment of the duties can be recommended to the patient and the employer. The knowledge of anatomy, kinesiology and ergonomics, together with the agreed work place adjustments, will allow the physiotherapist to focus on the treatment of the disease and prevent injuries when the patient returns to work. This will be done by addressing the physical function of the rest of the body which will help the patient maintain independence and confidence. CSP reports, Work Health and Fitness for Work 2014, highlight the role physiotherapy plays in patient’s physical and mental wellbeing and the effectiveness in reducing costs from the sickness absence through improving function and independence by providing advice to the patients and collaborating with the government and other health agencies to support patients to engage with work and influence employers in the decision making of the tasks allocation and management. Fitness Profits is a CSP leaflet which outlines the role of the physiotherapy and the benefits it would have for the patient.

Breast Cancer Recurrence[edit | edit source]

Patients need to be educated to know their bodies and signs and symptoms so if there is recurrence, patients can identify the signs and address this at an early stage. Clinicians should be educated on the potential breast cancer recurrence and have strategies in place to address a reoccurrence for each individual patient. The clinician are expected to know where to turn to within the MDT to treat any issues effectively. The sings and symptoms for reassurance of breast cancer varies between patients and the specific kind of breast cancer, there for clinicians need to undertake specific learning for their patient groups for these.

“Cancer control requires a multilevel strategy that intervenes at different stages of the disease” [58]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

|

Lymphodema |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Eyigor S, Kanyilmaz S. Exercise in patients coping with breast cancer: An overview. World J Clin Oncol 2014 08/10;5(3):406-411.

- ↑ Pidlyskyj K, Roddam H, Rawlinson G, Selfe J. Exploring aspects of physiotherapy care valued by breast cancer patients. Physiotherapy 2014;100:156-161.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cancer Research UK. Cancer Statistics. Cancer of the Breast. :11 November 2014.

- ↑ Langhorne ME, Fulton JS, Otto SE. Oncology nursing. : St. Louis, Mo. : Mosby Elsevier, c2007; 5th ed. / edited by] Martha E. Langhorne, Janet S. Fulton, Shirley E. Otto; 2007.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 EBAUGH, D., SPINELLI, B. AND SCHMITZ, K.H., 2011. “Shoulder impairments and their association with symptomatic rotator cuff disease in breast cancer survivors”, Medical Hypotheses. Vol. 77, pp. 481–487.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Pacurar R, Miclaus C, Miclaus M. Morbidity associated with breast cancer therapy and the place of physiotherapy in its management. Timisoara Physical Education & Rehabilitation Journal 2011 05;3(6):46-54.

- ↑ JOHNSON, S. and MUSA, I., 2004.Preparation of the breast cancer patient for radiotherapy planning. Physiotherapy. . Vol. 90, no. 4, pp. 195-203.

- ↑ Dahl AA, Nesvold I, Reinertsen KV, Fosså SD. Original Article: Arm/shoulder problems and insomnia symptoms in breast cancer survivors: Cross-sectional, controlled and longitudinal observations. Sleep Med 2011;12:584-590.

- ↑ Freitas-Silva R, de Freitas-Júnior, R. ( 1 ), Conde DM(2), Martinez EZ(3). Comparison of quality of life, satisfaction with surgery and shoulder-arm morbidity in breast cancer survivors submitted to breast-conserving therapy or mastectomy followed by immediate breast reconstruction. Clinics 2010 / 06 / 01 /;65(8):781-787.

- ↑ Harrington S(1), Padua D(2), Myers J(2), Battaglini C(3), Groff D(3), Michener LA(4), et al. Comparison of shoulder flexibility, strength, and function between breast cancer survivors and healthy participants. Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2011 / 06 / 01 /;5(2):167-174.

- ↑ Todd J, Topping A. A survey of written information on the use of post-operative exercises after breast cancer surgery. Physiotherapy 2005;91:87-93.

- ↑ ) Amaral MTPd, de Oliveira M,Maia Freire, Ferreira NdO, Guimarães R, Vidigal, Sarian L, Otávio, Gurgel MSC. Manual therapy associated with upper limb exercises vs. exercises alone for shoulder rehabilitation in postoperative breast cancer. PHYSIOTHER THEORY PRACT 2012 05;28(4):299-306.

- ↑ SAINI, K.S., TAYLOR, C., RAMIREZ, A.J., PALMIERI, C., GUNNARSSON, U., SCHMOLL, H.J., DOLCI, S.M., GHENNE, C., METZGER-FILHO, O., SKRZYPSKI, M., PAESMANS, M., AMEYE, L., PICCART-GEBHART, M.J. and DE AZAMBUJA, E., 2012. Role of the multidisciplinary team in breast cancer management: results from a large international survey involving 39 countries. Annals of Oncology : Official Journal of the European Society for Medical Oncology / ESMO. Apr, vol. 23, no. 4, pp. 853-859.

- ↑ Fleissig A, Jenkins V, Catt S, Fallowfield L. Review: Multidisciplinary teams in cancer care: are they effective in the UK? Lancet Oncology 2006;7:935-943.

- ↑ FISHER, B., ANDERSON, S., BRYANT, J., MARGOLESE, R.G., DEUTSCH, M., FISHER, E.R., JEONG, J. and WOLMARK, N., 2002. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized trial comparing total mastectomy, lumpectomy, and lumpectomy plus irradiation for the treatment of invasive breast cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. . Vol. 347, no. 16, pp. 1233-1241.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Beurskens CHG(1), van Uden, C.J.T. ( 1,2 ), Strobbe LJA(3), Oostendorp, R.A.B. ( 4,5 ), Wobbes T(6). The efficacy of physiotherapy upon shoulder function following axillary dissection in breast cancer, a randomized controlled study. BMC Cancer 2007 / 08 / 30 /;7.

- ↑ Johansen S, Foss K, Nesvold I, L., Malinen E, Foss S, D. Arm and shoulder morbidity following surgery and radiotherapy for breast cancer. Acta Oncol 2014 04;53(4):521-529.

- ↑ Schnur JB(1), Montgomery GH(1), Ouellette SC(2), Dilorenzo TA(3), Green S(4). A qualitative analysis of acute skin toxicity among breast cancer radiotherapy patients. Psychooncology 2011 / 03 / 01 /;20(3):260-268.

- ↑ Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF. Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1995 03/30;31(5):1341-1346.

- ↑ Yarnold J. Early and locally advanced breast cancer: diagnosis and treatment National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence guideline 2009. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2009 04;21(3):159-160.

- ↑ HICKEY, B.E., FRANCIS, D.P. and LEHMAN, M., 2013. Sequencing of chemotherapy and radiotherapy for early breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. , vol. 4.

- ↑ Monsuez J, Charniot J, Vignat N, Artigou J. Review: Cardiac side-effects of cancer chemotherapy. Int J Cardiol 2010;144:3-15.

- ↑ Senkus E, Jassem J. Complications of Treatment: Cardiovascular effects of systemic cancer treatment. Cancer Treat Rev 2011;37:300-311.

- ↑ Yeh E. Cardiotoxicity induced by chemotherapy and antibody therapy. Annu Rev Med 2006;57:485-498.

- ↑ McAnaw MB, Harris KW. The Role of Physical Therapy in the Rehabilitation of Patients with Mastectomy and Breast Reconstruction. Breast Disease 2002 12;16(1):163-174.

- ↑ Levangie PK, Drouin J. Magnitude of late effects of breast cancer treatments on shoulder function: a systematic review. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2009;116(1):1-15.

- ↑ Torres Lacomba M, Yuste Sánchez MJ, Zapico Goñi A, Prieto Merino D, Mayoral dM, Cerezo Téllez E, et al. Effectiveness of early physiotherapy to prevent lymphoedema after surgery for breast cancer: randomised, single blinded, clinical trial. BMJ (Clinical research ed ) 2010 / 01 / 01 /;340:b5396.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Courneya KS. Exercise in cancer survivors: an overview of research. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2003 11;35(11):1846-1852.

- ↑ Courneya KS, Friedenreich CM. Physical Activity and Cancer [electronic resource]. : Berlin, Heidelberg : Springer Berlin Heidelberg : Imprint: Springer, 2011; 2011.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 PANEL E. American College of Sports Medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. 2010.

- ↑ Miedema B, Easley J. Barriers to rehabilitative care for young breast cancer survivors: a qualitative understanding. Supportive Care in Cancer 2012;20(6):1193-1201.

- ↑ Leach H, Danyluk J, Culos–Reed S. Design and implementation of a community-based exercise program for breast cancer patients. Current Oncology 2014;21(5):267.

- ↑ Ottenbacher AJ(1), Day RS(1), Taylor WC(1), Sharma SV(1), Sloane R(2), Snyder DC(3), et al. Exercise among breast and prostate cancer survivors-what are their barriers? Journal of Cancer Survivorship 2011 / 12 / 01 /;5(4):413-419

- ↑ Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. Cancer survivors' adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society's SCS-II. J Clin Oncol 2008 2008;26(13):2198-2204.

- ↑ Turner, J. ( 1,4 ), Hayes S(2), Reul-Hirche H. Improving the physical status and quality of life of women treated for breast cancer: A pilot study of a structured exercise intervention. J Surg Oncol 2004 / 06 / 01 /;86(3):141-146.

- ↑ Monninkhof EM, Elias SG, Vlems FA, van dT, Schuit AJ, Voskuil DW, et al. Physical activity and breast cancer: a systematic review. Epidemiology 2007 01;18(1):137-157.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Brunet J, Taran S, Burke S, Sabiston CM. A qualitative exploration of barriers and motivators to physical activity participation in women treated for breast cancer. Disability & Rehabilitation 2013 12/25;35(24):2038-2045.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Blaney JM(1), Lowe-Strong A, Gracey JH(1), Rankin-Watt J, Campbell A(3). Cancer survivors' exercise barriers, facilitators and preferences in the context of fatigue, quality of life and physical activity participation: A questionnaire-survey. Psychooncology 2013 / 01 / 01 /;22(1):186-194.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 HEFFERON, K., MURPHY, H., MCLEOD, J., MUTRIE, N., CAMPBELL, A., 2013. Understanding barriers to exercise implementation 5-year post-breast cancer diagnosis: a large-scale qualitative study. Health Education Research [online]. Vol 28, no. 5, pp. 843-6 [viewed November 2014]. Available from: NCBI.

- ↑ LOH, S. Y., CHEW, S., LEE, S., 2010. Physical Activity and Women with Breast Cancer: Insights from Expert Patients [online]. Vol. 11, pp. 87-4 [viewed November 2014]. Available from: NCBI.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 41.3 PARAMANANDAM, V. S., & ROBERTS, D., 2014. Weight training is not harmful for women with breast cancer-related lymphoedema: a systematic review. Journal of Physiotherapy [online]. Vol. 60, no. 3, pp. 136-3 [viewed November 2014]. Available from: NCBI.

- ↑ Emery, C.F. ( 1,2,3 ), Yang H-(1), Peterson LJ(1), Suh S(1), Frierson GM(4). Determinants of physical activity among women treated for breast cancer in a 5-year longitudinal follow-up investigation. Psychooncology 2009 / 01 / 01 /;18(4):377-386.

- ↑ Bower JE, Ganz PA, Desmond KA, Rowland JH, Meyerowitz BE, Belin TR. Fatigue in breast cancer survivors: Occurrence, correlates, and impact on quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2000 / 02 / 01 /;18(4):743-753.

- ↑ Hayes, S. ( 1,2,4 ), Newman B(1), Cornish B(3). Comparison of methods to diagnose lymphoedema among breast cancer survivors: 6-month follow-up. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2005 / 02 / 01 /;89(3):221-226.

- ↑ Hayes SC, Janda M, Cornish B, Battistutta D, Newman B. Lymphedema after breast cancer: Incidence, risk factors, and effect on upper body function. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2008 / 01 / 01 /;26(21):3536-3542.

- ↑ Cheifetz O, Haley L. Management of secondary lymphedema related to breast cancer. Can Fam Physician 2010 12;56(12):1277-1284.

- ↑ MCKENZIE, D.C., A breast in a Boat - a race against breast cancer. Canadian Medical Assoc J [online]. Vol. 159, no.4, pp. 376-78 [viewed November 2014]. Available from: NCBI.

- ↑ Kwan ML, Cohn JC, Armer JM, Stewart BR, Cormier JN. Exercise in patients with lymphedema: a systematic review of the contemporary literature. JOURNAL OF CANCER SURVIVORSHIP-RESEARCH AND PRACTICE 2011;5(4):320-336.

- ↑ Schmitz KH(1), Troxel AB(1), Lewis-Grant L, Bryan CJ(1), Williams-Smith C, Chittams J(1), et al. Weight lifting for women at risk for breast cancer-related lymphedema: A randomized trial. JAMA - Journal of the American Medical Association 2010 / 12 / 22 /;304(24):2699-2705.

- ↑ Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Troxel A, Cheville A, Smith R, Lewis-Grant L, et al. Weight lifting in women with breast-cancer-related lymphedema. N Engl J Med 2009 08/13;361(7):664-673.

- ↑ LOH, S. Y., CHEW, S., LEE, S., 2010. Physical Activity and Women with Breast Cancer: Insights from Expert Patients [online]. Vol. 11, pp. 87-4 [viewed November 2014]. Available from: NCBI.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Burnham TR, Wilcox A. Effects of exercise on physiological and psychological variables in cancer survivors. / Effets de l ' activite physique sur les variables physiologiques et psychologiques des personnes en phase de remission d ' un cancer. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise 2002 12;34(12):1863-1867.

- ↑ World Health Organisation. The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. 2001; Available at: http://www.who.int/disabilities/world_report/2011/report.pdf. Accessed 15 November, 2014.

- ↑ Halm MA. Clinical evidence review. Relaxation: a self-care healing modality reduces harmful effects of anxiety. Am J Crit Care 2009 03;18(2):169-172.

- ↑ Robotin M, Olver I, Girgis A. When cancer crosses disciplines : a physician's handbook. : London : Imperial College Press, c2010; 2010

- ↑ Unruh, A. and Elvin, N. (2004). In the eye of the dragon: Women's experience of breast caner and the occupation of dragon boat racing. R EVUE CANADIENNE D ’ ERGOTHÉRAPIE, 71(3), pp.138-149.

- ↑ Waddell, G., Burton, A.K and Kendall, N.A.S. Vocational Rehabilitation: What Works, for Whom and When?

- ↑ HIATT RA, RIMER BK. Principles and Applications of Cancer Prevention and Control Interventions. Cancer Epidemiology and Prevention 2006.

- ↑ Keeley V, Crooks S, Locke J, Veigas D, Riches K, Hilliam R. A quality of life measure for limb lymphoedema (LYMQOL). J LYMPHOEDEMA 2010 04;5(1):26-37.

- ↑ Mendoza TR(1), Wang XS(1), Cleeland, C.S. ( 1,4 ), Morrissey M(1), Johnson BA(1), Wendt JK(1), et al. The rapid assessment of fatigue severity in cancer patients: Use of the brief fatigue inventory. Cancer 1999 / 01 / 01 /;85(5):1186-1196.

- ↑ Yellen, S.B. ( 1,3 ), Cella DF(1), Webster K(1), Blendowski C(1), Kaplan E(2). Measuring fatigue and other anemia-related symptoms with the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) measurement system. J Pain Symptom Manage 1997 / 02 / 01 /;13(2):63-74.

- ↑ Hudak, P.L. ( 1,2 ), Amadio, P.C. ( 1,3 ), Bombardier, C. ( 2,4 ). Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: The DASH (disabilities of the arm, shoulder, and head). Am J Ind Med 1996 / 01 / 01 /;29(6):602-608

- ↑ Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983 06;67(6):361.