Physiotherapists as Advocates for Individuals Living With Dementia

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Dementia is a global health priority, affecting populations worldwide[1]. Health care issues, including dementia, are taking center stage in both political and media discussions, and health professionals, including physiotherapists, must be ready to participate in these discussions with confidence and influence. The Scottish Government’s Proposal for Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy 2016-19[2], states the need for continued support to improve all areas of dementia care, at all stages of the condition. It is crucial that individuals with dementia receive the care and services they require and are not dis-empowered or discriminated against due to their condition. The Proposal for Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy 2016-19 also priorities “enhancing a multi-disciplinary approach to care at home, including the promotion of the therapeutic and enabling role of AHPs for people with dementia”[2] (pg. 7). By taking on the role of advocate and tackling key issues related to dementia and dementia care, physiotherapists can ensure the rights of every individual are being upheld, that each person is receiving the best possible care, and that no individual living with dementia is victimised or discriminated against. Due to the many myths and misconceptions surrounding Dementia, there is a growing need to educate Physiotherapists about the value and importance of being advocates. The following video, Share the Orange, describes dementia and it's effects on an individual

What is Advocacy?[edit | edit source]

Advocacy involves speaking out on behalf of another individual or group of individuals in a way that represents their best interests. The New Penguin English Dictionary[4] defines advocacy as “active support or pleading”. From this definition it can be implied that advocacy entails supporting someone by actively acquiring resources for them or on their behalf. There are many different forms advocacy can take, such as self-advocacy, legal advocacy and independent advocacy, and anyone who possesses the necessary skills can act as an advocate. In health care, advocates act according to the patient’s values and wishes and advocacy can be seen as part of the therapeutic relationship between the patient and health care professional[5]. It involves informing the patient of their rights, ensuring they have the required information to make informed decisions, supporting the patient in their decision, and protecting their interests and rights[6]. Advocacy is also about influencing decision-making, and health care professionals use this skill everyday. Whether it is persuading a patient to stop smoking, convincing colleagues to improve patient care or ensuring a patient has access to the services they require, advocacy is taking place.

Why is Advocacy Important and Who Requires One?[edit | edit source]

Advocacy arises as a result of working with people who are disadvantaged in some way. Individuals working with groups who are marginalised in society, such as the elderly, ethnic minorities, or individuals with disabilities, must be prepared to act as advocates on their behalf. Since advocacy involves aiding and supporting individuals or groups, it fits into the range of fundamental activities performed by health-care professionals. Advocacy can provide an element of informed and compassionate health care planning and delivery that is available from no other source[6]. Every individual has equal rights to access the services they require, but particular populations or individuals may be unable to protect their own rights or access services. It is vital that individuals who are dis-empowered in some way are not subject to inadvertent discrimination or decreased access to services because of their circumstances. Advocacy is a mechanism through which individuals’ rights are enabled and protected.

Advocacy may include supporting an individual to[7]:

- The right to confidentiality and privacy

- The right to dignity and respect

- The right to quality services

- The right to choice and control

- The right to information to inform decision making

- The right to non-discriminatory service

- The right to make complaints

- The right to protection of legal and human rights, and freedom from abuse and neglect

Individuals require advocates for various reasons. As discussed above, advocacy comes from working with people who are disadvantaged in some way. These disadvantaged populations are vulnerable and often marginalised in society. They may be momentarily vulnerable, weakened by illness or injury; or distressed by a loved one’s suffering, disability, or death. Often these populations may have difficulty self-advocating and may struggle to protect their own rights. They may include ethnic minorities, people with disabilities, the elderly, and individuals living with dementia.

What Skills or Attributes are Required to be an Advocate in Health Care?[edit | edit source]

There are no uniformly accepted educational requirements to be an advocate in health care[5], but Kelland and colleagues[8] interviewed 17 self proclaimed leading advocates in the field of physiotherapy and have proposed eight attributes a physiotherapist must display competence in, in order to be successful in the role of advocate. Others have noted similar characteristics required for a health professional to be successful advocates[5][6].

The attributes are listed below:

- Collaboration

Physiotherapists must collaborate with multiple people in various ways. It is important to understand the roles of other health professionals in order to collaborate and best meet the needs of the patient. Physiotherapists must also collaborate with their patients and their families to ensure effective patient-centred care. - Communication

It is important to know one’s audience and to adapt one’s communication style accordingly. Physiotherapists must be good listeners and be able to speak out when necessary. Listening is critical to understanding the needs of others and is a valuable first step to empowering patients to advocate for themselves. - Scholarly practice

In order to be a successful advocate, one must understand whom they are advocating for, their mission, and what their needs are. By researching and demonstrating that there is a need for advocacy in a particular area, more will be achieved. It is important to have sufficient and accurate data and research before speaking out. - Management

To be a successful advocate, physiotherapists must understand aspects of management and how these factors might affect one’s ability to advocate for patients. For example, it is important to understand financial, funding, and service delivery model factors that impact a physiotherapist’s ability to advocate for patients. - Professionalism

It is important to engage in professionalism and take on roles beyond those of a clinician. This includes showing a commitment to improving the overall health care patients receive, not necessarily only to physiotherapy. - Passion

When one is passionate about the issue at hand, advocacy will be easier. However, it is important to balance and keep emotions in control; there is a place for passion, not for anger. - Perseverance

Advocacy is often a long-term venture and thus perseverance is an important quality to possess. - Humility

Physiotherapists must be able to reflect on whose agenda they are advocating and commit to advocating for that agenda, even if it is not their own. It is essential to understand the needs and priorities of other people.

Five of these attributes, collaboration, communication, scholarly practice, management and professionalism, overlap with current standards for practice for physiotherapy defined by the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) and the Chartered Society for Physiotherapists (CSP), and represent acquired skills. The other three, passion, perseverance, and humility are additional and individual to the role of advocate. Therefore, this indicates that all physiotherapists within the UK currently possess over half of the attributes for successful advocacy and thus are well equipped to take on this role. For physiotherapists to be successful as advocates, they must have to ability to integrate and adapt the above 8 attributes in practice.

The CSP’s Physiotherapy Framework[9] lists “advocacy” as an expected value of all CSP members, while the HCPC Standard of conduct, performance and ethics[10] state that health care professionals must “promote and protect the interests of service users and carers”. While this does not specifically include advocacy as a role, the words protect the interests of fall into the earlier mentioned definition of advocacy. By understanding the role of advocate and what attributes are needed for successful advocacy, physiotherapists of all levels of experience can be advocates and ensure patients have their rights protected and are receiving the best care. Therefore, this makes physiotherapists suitable and capable advocates for individuals living with dementia.

Advocate’s Attitudes and Beliefs[edit | edit source]

The three above mentioned attributes to successful advocacy, passion, perseverance, and humility, represent personality characteristics and can be interconnected with an advocates attitudes and beliefs. Advocates must have clear, focused and structured ethical beliefs and values so that their efforts are concentrated on the advocacy task, and not distracted, when ethical problems arise. The HCPC Standards of conduct, performance and ethics outline structured ethical codes for health professionals in the UK to follow and adhere to for practice[10]. The HCPC Standard of proficiency[11] further assists to clarify the physiotherapists’ ethical obligations and minimise ethical dilemmas. For example, HCPC Standard of proficiency 2.1 states physiotherapists must “act in the best interests of service users at all times”. In the role of advocacy, this means that advocates should always remember whom they are acting for and what the goal of their action is. HCPC Standard of proficiency 7 states that physiotherapists should “be able to understand the importance of and be able to maintain confidentiality”; patients must feel safe knowing that what they say is confidential and confidentiality essential to building an honest relationship between advocate and patient[11].

Advocacy has historically been separate from service providers and other services. This independence safeguards from the possibility of conflict of interest arising from any of the services accessed by the individual requiring advocacy[12]. It is crucial that when assuming the role of advocate, physiotherapists remain free from conflict of interest so that the individual is in control and has a sense of ownership over the situation. In addition, the advocate must be honest and straightforward with the patient regarding his or her own values and beliefs. At times, the individual’s wishes and instructions may conflict with the values and beliefs of the advocate. The advocate must be able reconcile their own ethics and values with their duty to the patient. If they cannot, then the advocate must reconsider whether they are ready to be an advocate at all. The HCPC Standards of conduct, performance and ethics 9.4 states that health care professionals “must declare issues that might create conflicts of interest and make sure that they do not influence [their] judgment”[10]. Health care professionals, including physiotherapists, have the same values, beliefs and ethics as needed for successful advocacy, thus further making them well suited for the role.

HCPC Standards of conduct, performance and ethics outlines standards that all HCPC registrants must meet in order to practice in health care, while the HCPC Standards of proficiency for physiotherapists are the minimum standards that physiotherapists adhere to for the safety of the public. The CSP’s Physiotherapy Framework describes the knowledge, skills and behaviours required of a physiotherapist and is used to promote and develop physiotherapy practice. It outlines a number of inter-related domains that are fundamental to physiotherapy practice[11][10][9]. The following table highlights how professional standards promote advocacy and care.

|

Attribute |

HCPC Standard and/or CSP Physiotherapy Domain |

|

Collaboration |

HCPC Standard of Proficiency #9: “be able to work appropriately with others” CSP Domain: “Promoting integration & teamwork” |

|

Communication |

HCPC Standard of Proficiency #8: “be able to communicate effectively” |

|

Scholarly practice |

HCPC Standard of Proficiency #14: “be able to draw on appropriate knowledge and skills to inform practice” |

|

Management |

HCPC Standard of Proficiency #14: “be able to draw on appropriate knowledge and skills to inform practice” |

|

Professionalism |

HCPC Standards of conduct, performance and ethics #9: “be honest and trust worthy: personal and professional behaviour” |

Collaboration is the first attribute outlined as an essential attribute required for successful advocacy by physiotherapists. According to the HCPC[11], all physiotherapists must be able to collaborate with other professionals, with service users as well as support staff and others involved such as family members and carers. It also states that physiotherapists should engage the service user and family in all aspects of the services users care. The CSP’s Physiotherapy Framework outline one of the integral domains of physiotherapy is promoting teamwork and integration, which involves “the process of working with others to achieve shared goals”[9]. In order to achieve the shared outcome from advocacy, physiotherapists must work with others effectively.

Effective communication is essential to physiotherapy practice, as well as successful advocacy. The HCPC require physiotherapists to successfully communicate through verbal and non-verbal means[11]. Communication also involves providing the service user with appropriate information so that they can make informed decisions, critical in effective advocacy. The CSP’s Physiotherapy Framework state communicating to be a vital domain in physiotherapy practice and communication must be modified to each individual’s needs and preferences, a key skill required for effective advocacy[9].

Scholarly practice is also indicated as central to practicing advocacy. The HCPC expect physiotherapists to understand the structure of health and social care services and be able to research and collect appropriate information while problem solving and critically evaluating the information gathered[11]. The CSP asserts essential skills of all physiotherapists are that of researching, evaluating practice, and knowledge of the profession. This includes knowledge and understanding of other professions in health and social care, fundamental in health care advocacy. Physiotherapists must be competent in collecting and analyzing data in order to successfully advocate on behalf of their service users[9].

Management is a further attribute outlined as essential for effective advocacy. HCPC Standard of Proficiency 14.1 states that physiotherapists must “understand the structure and function of health and social care services in the UK”[11]. This means that physiotherapists must have knowledge and understanding of policies, service delivery models and funding systems applicable to the individual or group they are acting as advocates for. The CSP’s Physiotherapy Framework domain, “political awareness”, states the importance of understanding and identifying economic, social and political factors that influence the delivery of health and social care. An additional domain, “managing self and others”, requires that physiotherapists adapt their behaviours and actions to fit the demands of different situations. By being politically aware and adaptable, physiotherapists are demonstrating that they possess the essential skills and behaviours for advocacy[9].

The final attribute of advocacy that reflects the HCPC and CSP’s essential skills and conduct for physiotherapy practice is that of professionalism. The HCPC Standards of conduct, performance and ethics ensures that health professionals are honest and display behaviours that are trustworthy, ensuring the public have confidence in the profession. The public’s confidence in a health professional strengthens the therapeutic relationship, making advocacy more effective[10]. The CSP’s Physiotherapy Framework outlines the values of practicing physiotherapists. They include honesty and integrity as well social responsibility and commitment to excellence, all necessary for success in the role of advocate. The framework also includes the domain of “respecting and promoting diversity”. This indicates that physiotherapists examine their own values and beliefs to prevent discriminatory behaviour, an attribute essential to effective advocacy[9].

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

There are an estimated 850,000 people living with dementia in the UK today[13]. This is expected to increase to one million people by 2025 and then double to two million by 2050[14]. This predicted increase is a worldwide problem with the global number of people living with dementia predicted to increase from the current 46.8million to 130million by 2050[15].

From the 850,000 people affected in the UK, 62% are female[14]. Although dementia is a disease associated with the elderly population, 45,000 of the total number of people living with dementia are under 65 years old[14]. Although around 95% of people living with dementia will be older, it is important to recognize that it can affect younger patients and that there may be extra challenges that come along with that. Werner et al.[16] stated that persons diagnosed with dementia who are under 65 years have increased emotional and psychological difficulty compared to those over 65 due to a role reversal, in that children will now be the caregiver for parents earlier than expected and the loss of employment causing a reduction in self-efficacy and worth.

These statistics shows that Dementia is a worldwide health issue, which unfortunately is on the increase. As physiotherapists, we are likely to encounter patients living with dementia in many different environments and with the estimated population of diagnosed individuals set to increase, working with these patients and their carers could be a bigger part of our role.

Types of Dementia[edit | edit source]

Dementia is an umbrella term for a loss of cognitive function caused by damage to the brain. Dementia UK[17] suggest there are four main types of Dementia (ranked most to least common):

| 1. | Alzheimer’s Disease |

| 2. | Vascular Dementia |

| 3. | Frontotemporal Dementia |

| 4. | Dementia with Lewy Bodies |

Each of the different types of Dementia have different presentations and the patient may experience different symptoms.

Alzheimer’s Disease[edit | edit source]

The most common type of dementia is a gradual progressive disease that affects 60% of dementia diagnosed patients and predominately those over 65. The damage is due to proteins (amyloid and tau) malfunctioning in the brain which causes brain cells to die. It may also be due to a reduction in the neurotransmitter acetylcholine leading to information not transmitting.

Alzheimer’s disease affects five areas of the brain – memory, insight, cognitive ability, spatial awareness and language. Symptoms may include: poor memory resulting in losing items and repeating oneself; poor organisational skills, inability to make decisions and increasing difficulty with conversations; misuse of words; increased confusion and easily disorientated.

Vascular Dementia[edit | edit source]

This type of dementia is caused by transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) in the brain resulting in areas of brain damage. In this type of dementia the progression is usually more step-like with periods of remission where the person stays at the same level for a period of time. Language and communication are likely to be most affected in this type of dementia but some people are diagnosed with ‘mixed dementia’ which is a combination of vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease – this would mean there would also be significant deficits in memory.

Frontotemporal Dementia[edit | edit source]

Most commonly diagnosed in those under 65 years, this part of dementia affects predominantly behaviour and personality due to the frontotemporal lobe being mostly affected. It is gradual and progressive and the main symptoms include loss of inhibition and inappropriate behaviour

Dementia with Lewy Bodies[edit | edit source]

Changing cognitive impairment and movement are commonly affected in Dementia with Lewy Bodies. It can have a similar presentation to Parkinson’s disease with people having tremors and shuffling gait patterns. Hallucinations are another symptom along with difficulty sleeping and swallowing.

Why Are These Patients Vulnerable?[edit | edit source]

The Oxford Dictionary (2016) defines “vulnerable” as “in need of special care, support or protection because of age, disability or risk of abuse or neglect”. As we have covered already, people living with dementia could have problems with decision making, sequencing which will affect their ability to perform activities of daily living, remembering to do important things (for example, turn the stove off) and they can be easily disorientated making it easier for them to become lost when outside. All of these examples will make this person vulnerable to physical or emotional harm because of their impairment. It is important when working with these patients to recognise how far along in their dementia journey they are. There are many decisions and tasks they may still be able to make and do whilst there are others they will require support for. As a vulnerable group, these patients will need people advocating for them and there's no reason why it shouldn't be physiotherapists.

In order to gain a greater insight in to how it feels to be living with dementia, you can download a virtual reality app “A Walk through Dementia” available at this website: http://www.awalkthroughdementia.org

You can also watch the video of how and why Alzheimer’s Research UK developed the Walk through Dementia project:

Physiotherapists Treating People Living with Dementia[edit | edit source]

Alzheimer’s Society[19] collected quantitative and qualitative data through a study which consisted of questionnaires for carers, nursing staff and ward managers of acute hospitals. They reported that at any one time one quarter of patient beds will be taken up by patients with a dementia diagnosis. On top of this, they will on average have a longer stay in hospital for the same procedure as someone without diagnosed dementia. The CSP[20] reported that two thirds of people with dementia are still living in their own homes with the remainder in a care home setting. It is inevitable then, that as physiotherapists, we are going to have contact with dementia patients in acute hospitals and out in the community.

Unfortunately in the Alzheimer’s Society report[19], 77% of carers were dissatisfied with the dementia care given in hospital and two of the main problems identified were:

- Staff not having enough time with patients

- Problems with discharge which included lack of access to physiotherapy

It has been shown that physiotherapists are able to improve the quality of life and physical function of people living with dementia through exercise interventions therefore we should be seeing patients in hospital and at home.[21][22][23][24]

Fortunately we have more time to spend with patients for treatment than nurses or doctors. If we allowed patients access to physiotherapy it would solve both problems identified in the study. This extra time will allow us to build good relationships and allow us the opportunity to advocate for these patients.

If you would like to further increase your knowledge about Dementia and learn how to be more helpful to people living with Dementia, you can sign up to be a Dementia Friend at this website: http://www.dementiafriendsscotland.org/

Advocacy Against Discrimination[edit | edit source]

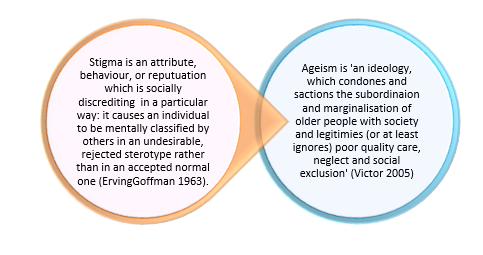

To become an anti-discrimination advocate on behalf of people living with dementia, you must understand what discrimination means. Beside the legal definition, it generally means treating someone unfairly relative to others. We can distinguish stigma and discrimination in relation to dementia by saying that a person with dementia can be ‘stereotyped’ (stigma) which can give rise to prejudice/bias against the person whereby they are treated unfairly (discrimination).

The Stigma and Discrimination People Living with Dementia Face[edit | edit source]

One of the most prominent characteristics of dementia discourse is the pivotal role that stigma plays in defining the experience of the condition[25]. The World Health Organization recognizes that, ‘‘stigma against older people with dementia is widespread, and its consequences far reaching’’[26].

Figure 1 - Defines stigma and ageism which are both forms of discrimination[27][28].

Figure 1 - Defines stigma and ageism which are both forms of discrimination[27][28].

Age discrimination is also a key factor[29]. As aforementioned, dementia is predominantly an illness associated with later life, hence the risk of developing Alzheimer's disease increases significantly with age. As an age-related disorder, older people with dementia are exposed not only to the stigma associated with mental illness, but to age discrimination as well – the so-called “double whammy”[30]. Old age stereotypes are commonly negative and are associated with dependency, limited social lives and incapacity to exercise autonomy[28]. Ageism is the most socially condoned form of prejudice and has a negative impact on the welfare and wellbeing of older people in the UK and as a barrier to inclusion[31]. Specifically, it contributes to feelings of worthlessness and despair, lowers self-esteem and expectations, limits access to services, and underpins a lack of respect shown to older people[32]. Ageism can also intersect with other dimensions of social inequality such as gender, race or disability. Older women for example, report that they felt “overlooked” and “useless”, a manifestation of the combined impact of sexism and ageism[33].

Ageist attitudes combine with the process of stigmatization as identified above, to undermine the development of good practice amongst healthcare professionals, and contribute to the defeatism, therapeutic nihilism and enduring pessimism that routinely characterize services for people with dementia[34]. Assumptions that dementia is a normal and inevitable part of the ageing process and that it is not amenable to intervention are also common features. Such attitudes serve to undermine the autonomy and decision-making capacity of people with dementia which will be discussed later in this wiki. They have also been associated with abuse and neglect, premature institutionalization, and inadequate care[35]. A number of studies show that service users with advanced dementia are often perceived as “effectively dead” or as “pitiful victims” who need looking after[36]. Additionally, Livingstone et al.[37] reported that people with dementia may not be capable of enjoyment or experiencing a satisfactory, or even good quality of life. These views are reflected in the widespread public perception of dementia as an incurable condition about which “nothing can be done”[38]. The invisibility of many people with dementia to public gaze amplifies this tendency and contributes to their social exclusion and low status[29]. "Labels can become so frustrating, as instead of being reffered to 'Jim', 'Pat', 'Lucy' or 'Ann', you suddenly morph into a person with dementia first, followed by your name and other qualities. It's as if the rest of a person has vanished into this air, never to return" Linda Hogg - Person living with Alzheimers''[31]

Overcoming stigma will help tremendously with achieving this wiki’s vision of an improved quality of life for people with dementia and their carers, and will give a greater understanding and empathy by those unaffected by dementia. As the community is aging[39] with a concurrent increase in the number of people living with dementia, there will be an increased demand for physiotherapists in geriatric arenas. Therefore the caseloads of physiotherapists and other AHP’s are becoming (if not already!) predominantly geriatric patients. This is why physiotherapists need to be advocates for anti-discrimination for people with dementia.

What Can Be Done to Tackle Stigma and Discrimination?[edit | edit source]

Public policy has a pivotal role to play in challenging the stigmatization and discrimination faced by individuals living with dementia. The Government acknowledged the discrimination faced by older people, including those with dementia, and the negative impact it has on their lives and health[40].

The Equality Act[41] makes it illegal for people to be treated less favourably because of their age, disability, gender, race, religion or belief, sexual orientation or transgender. The act requires public bodies to fully consider the impact that changes in policy, such as the closure of a service, can have on people with “protected characteristics” such as disabilities. In addition, the act continues the duty of service providers and employers to make “reasonable adjustments” to ensure that people with disabilities are not discriminated against.

The National Dementia Strategy (2010-2016) has specifically identified ‘‘addressing stigma and raising public awareness about dementia’’ as one of its primary objectives[42]. Presenting positive images of people living with dementia in the media could make a significant contribution to demystifying the condition and the challenging negative attitudes that currently pervade public opinion. Improving the quality and variety of services for people living with dementia and the treatment and care pathways they receive is an essential component of addressing stigmatisation and discrimination. This is also a key objective of the National Dementia Strategy: it highlights a need to ensure that services are flexible, reliable and accessible; range from early intervention to specialist home care; and are responsive to personal needs and preferences[42].

Appropriate care is vital in ensuring the dignity of people with dementia, who have often been considered more as ‘patients’ than people. There is a need for a care paradigm that puts the person and his or her needs as the central focus. Through advocacy and knowledge of these policies/guidelines and continued professional development, physiotherapists can help discourage and prevent discrimination and stigmatization.

Through increased knowledge and understanding the aim will be to:

- End discrimination because of reduced mental capacity. Lack of capacity can make people with dementia vulnerable to discrimination and treatment that contravenes their human rights. For instance, people with dementia can be excluded from discussions about their care and support and lack the capacity to challenge this exclusion. Under the Mental Capacity Act[43], a person is presumed to be able to make their own decisions "unless all practical steps to help them to make a decision have been taken without success". AHP’s have a responsibility to campaign for robust enforcement of this provision.

- End age discrimination towards older people. People with dementia are more likely to be over 65 and, in consequence, can face both ageism and the stigma associated with dementia. For example, older people are often denied access to the full range of mental health services that are available to younger adults. This is particularly disadvantageous towards older people with dementia who and require mental health support. There is also a widespread assumption that dementia is merely "getting old" rather than a serious disease. This has resulted in unequal treatment for people with dementia, including poor rates of diagnosis and a lack of appropriate services[44].

- End age discrimination towards younger people. Dementia is not just an older people's condition. In 2013, there were 42,325 people with early-onset dementia (onset before the age of 65 years) in the UK[45]. Young people with dementia can also face discrimination.

- Improved support for people from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities[46]. The number of people with dementia from BAME communities is expected to increase seven times by 2051[47]. However, people from BAME communities are less likely to be diagnosed or receive post-diagnosis support[48]. They face significant barriers when accessing support. There is a lack of culturally sensitive dementia services and families can be reluctant to use services that do not meet cultural or religious needs. Physiotherapists and other AHP’s need an increased awareness, better focus on preventative services, local community action and improved access to services for people from BAME communities[47].

- Improved care and support. The importance of good quality care is highlighted in dementia strategies and action plans in the UK[49]. However, there is currently unacceptable variation in the quality of formal care provided to people with dementia[50]. Poor care and support is believed to breach the rights of people with dementia and those who care for them to not be treated in an inhuman or degrading way, the right to respect for private and family life and the right to liberty.

- Robust action on abuse. Abuse and mistreatment is a serious infringement of the Human Rights Act. People with dementia may be subject to mistreatment and abuse in the community or in care homes and hospitals. This may include psychological, financial, emotional, sexual or physical abuse.

Human Rights-Based Approach[edit | edit source]

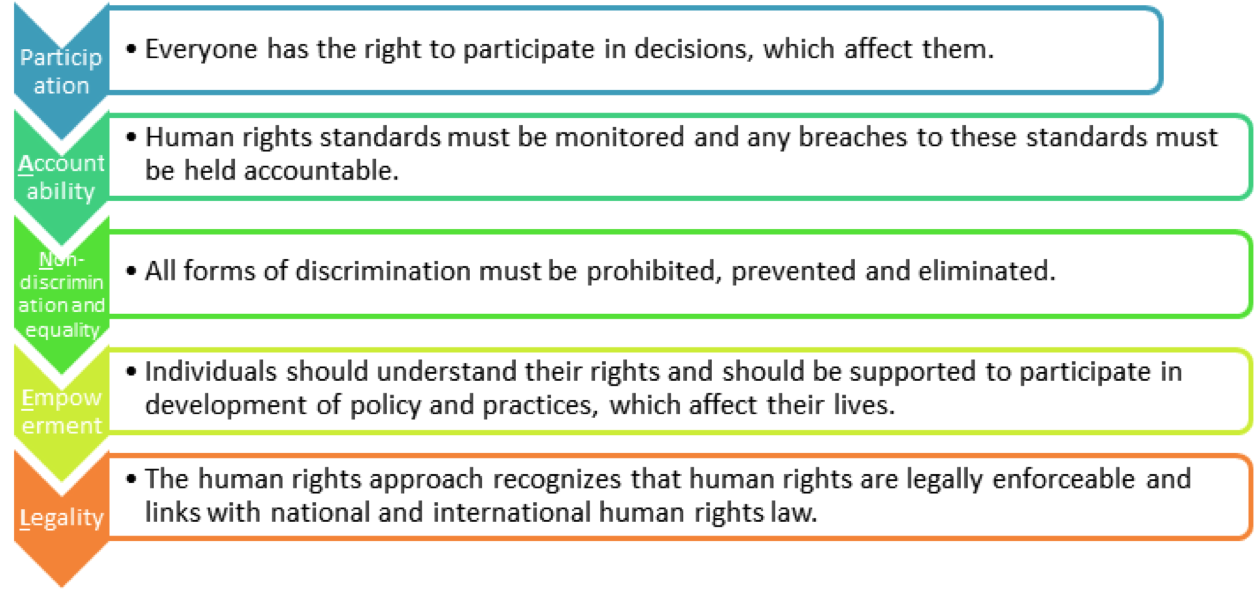

Physiotherapists can apply a human rights-based approach in practice to ensure successful advocacy for individuals living with dementia. By incorporating these five central principles into practice, physiotherapists can become better equipped to advocate for the rights of their patients. The PANEL principles[47] are fundamental to ensuring individuals are aware of their rights while also increasing the accountability of those responsible for protecting and respecting human rights.

Figure 2 shows the PANEL principles outlined by Alzheimer’s Society [47] .

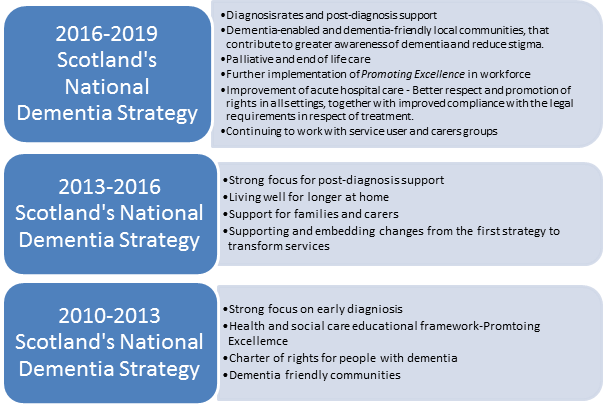

Scotland's National Dementia Strategy 2016-2019[2]

This is Scotland’s third National dementia strategy and is aligned with the 2020 Vision for Health and Care in Scotland. It sets out the progress and achievements since 2010 and more importantly the focus for the next three years. This strategy is heavily based on the rights of people living with dementia and their carers. They are entitled to dignity and respect and should be able to access services that provide support, care and treatment in a way that meets their personal needs.The goal was for all people with dementia and their carers to ‘live well with dementia’ and the strategy recognised that significant improvements were required in all aspects of care, which could be achieved through better education and training for professionals. The physiotherapists play an imperative role towards meeting these standards while working alongside other AHP’s, therefore it is important to be aware of ‘The National Dementia Strategy’ as a newly qualified physiotherapist, working with people living with dementia. For more detailed information, please see Scotland´s National Dementia Strategy 2013-2016, in full[51].

Figure 3. Outcomes for Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy from 2010-2016. What has been achieved since 2010 and outlines the focus for what needs to be done over the next three year period, 2016-2019[2][51].

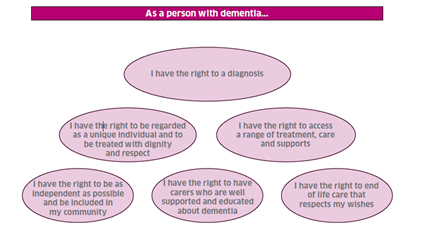

Rights-based Care[edit | edit source]

In the first Dementia Strategy, a commitment was made to the production of standards of care for dementia in Scotland. Too often, people with dementia experience discrimination and treatment that contravenes their human rights. People with dementia and carers should be treated with dignity, and receive care and support that is based on individual needs, rather than assumptions about the condition. Therefore there must be significant work by physiotherapists and other AHP’s to dispel the stigma of dementia to challenge this inequality. The dementia standards are based on six overarching statements of individual rights as illustrated in the Figure 4[52]

The Scottish Parliament’s Cross-Party Group on Alzheimer’s disease published a Charter of Rights for People with Dementia and their Carers. The document was based on the recognition that a great stigma existed about individuals with dementia and that people with dementia and their carers often experience discrimination and isolation. The document established that individuals with dementia and their care providers have the right to participate in the decision making process, are accountable for human rights and freedoms, can be free from discrimination, and should consider themselves empowered to access all levels of care and have the full range of legal human rights regardless of their situation. Scotland’s production of a ‘framework’ document could be a strong template for disseminating information in other national plans.

Moreover, the Standards of Care for Dementia recognise and acknowledge the importance of people with dementia being able, not only to stay at home and in their community, but they should also be, as much as possible, visible, connected and active participants in their local communities, including social events, arts and religious or community groups. In 2013, a new initiative programme focused on areas such as developing dementia friendly and enabled communities, peer support and befriending. The physiotherapist’s role is clearly identified here, as referenced in section 2 above, to use the standards to advocate equality for the patient.

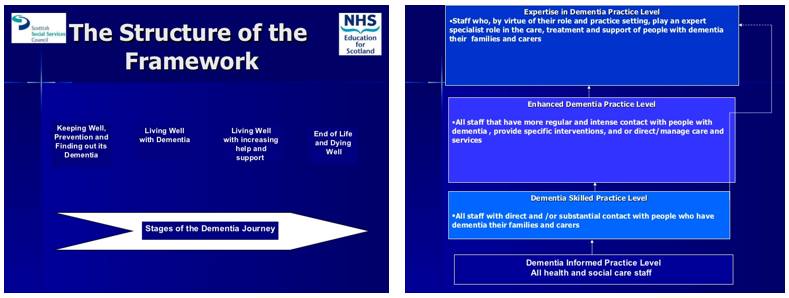

Promoting Excellence[edit | edit source]

The framework ‘Promoting Excellence’[53] details the knowledge and skills expected of all health and social service professionals in NHS Scotland working with people with dementia, their families and carers. It aims to support delivery of the aspirations and change actions outlined in ‘Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy’. This framework applies to all health and social services staff who have contact with, and provide support, care, treatment and services for people who have dementia, and their families/carers. Therefore, it applies to you! This will provide the basis for revising qualifications and developing specific training to fill gaps and to inform leadership development. The development of the framework was underpinned by values and principles reflecting views and opinions of patients with dementia, their families and carers. It is also heavily based on the ‘Standards of Care for Dementia in Scotland’[52]. As dementia is a progressive disease, the framework is split into four stages, which explains your expected knowledge base and responsibilities in relation to people with dementia.

'Figure 5 'displays the structure of the framework (left) and the 4 levels of staff experience or expertise (right).

Advocacy for Changing Attitudes[edit | edit source]

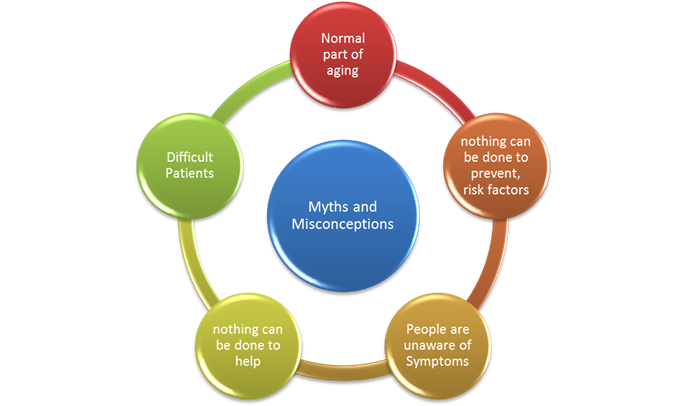

Due to the many Myths and Misconceptions surrounding Dementia, there is a growing need to educate Physiotherapists about the value and importance of being advocates.

Myths and Misconceptions[edit | edit source]

We have all heard of Dementia, the above activities should have given you a greater understanding of this disease which affects many of our patients. So why do we need to advocate for people living with Dementia? When you see on a patients notes “cognitive impairment” “Dementia” what do you think to yourself? Have you got preconceived ideas of how this person will comply with treatment? If yes then you are not the only one. There are worldwide common misconceptions about people living with dementia. Many people have these misconceptions due to misinformation and lack of education. Several themes emerge from the literature relating to the lack of awareness and understanding of dementia among the public[54].

These myths and misconceptions have resulted in Dementia not being a priority for healthcare provision. This therefore leads to vulnerable people not receiving the benefit from the positive intervention and support that can promote well-being and prevent crises for all involved. In the UK only one third of people living with dementia receive a diagnosis. When these individuals do receive a diagnosis it is often to late and at a time when the individual and their family are in crisis[54][55]. People are unaware of the common symptoms of Dementia. In response to of the “Facing Dementia Survey” 81% of respondents conducted in Europe believed that most people do not know the difference between the early stages of Alzheimer’s disease and behavior associated with normal ageing[56].There is a worldwide lack of understanding of the associated risk factors for Dementia Health problems such as hypertension and cholesterol are risk factors , therefore, an understanding of this link can encourage lifestyle modifications[57]. In a focus group lead study of 34 adults aged between 52-90 aiming to identify themes and categorize data on dementia knowledge, risks and attitudes. High dementia awareness was shown at group level but on a individual level knowledge was poor. The majority of participants feared dementia. They expressed that their main barriers were lack of knowledge and their main motivators were education and fear of developing dementia. Although there are limitations to this study the participants had a mean education years of 14.5 which is not an accurate representation of the general public and the recruitment process was aimed at attracting individuals with an interest in learning about dementia and therefore may not be a true representation of the general public[58]. Governmental strategies have a powerful influence on the thinking of health professionals which can lead to changes in attitudes and practice as well as providing vital support for development of existing services. The increasingly dramatic statistics showing increasing rise in the population of people living with dementia will need to be supported by governmental policy.

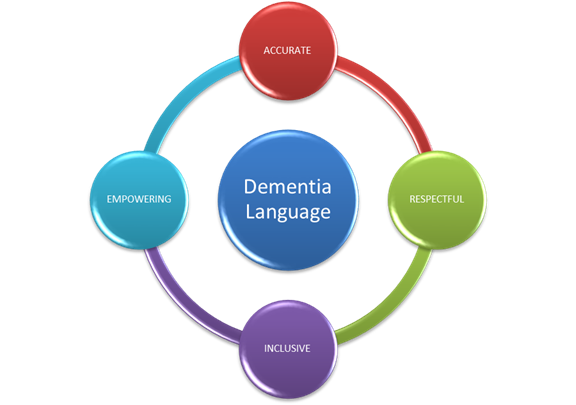

Language[edit | edit source]

Language is powerful, it can influence mood, self esteem, happiness and depression. Language surrounding Dementia often has negative connotations. These negative attitudes can have a profound impact on the person living with dementia and also their family and carer’s. It can also have an impact on people's attitudes to Dementia and lead to discrimination or stigma[59].

With regard to language we as health professionals need to be mindful of not reinforcing stereotypes or myths with our use of language.

Talking about dementia in a negative manner or by using incorrect terminology or inaccurate facts can lead to reinforcement of stereotypes and further exacerbate the myths and misinformation about dementia amongst other healthcare professional and the general public[60].

Healthcare Staff[edit | edit source]

Healthcare staff including physiotherapists are found to be friendly and hardworking with regards to caring for people living with Dementia but they are found to be lacking the specific skill set to effectively work with this patient cohort[61]. Whilst staff members realize their need to improve their knowledge and recognize the need for further education about Dementia dementia[62]. Interestingly it has been found that the greatest gap in education for healthcare staff working with people living with Dementia was in service training[63]. Due to these myths and misconceptions there is great need for us as physiotherapists to advocate for our patients living with Dementia. We can dispel these myths by being informed of the appropriate ways to treat a person living with Dementia and how we can adapt our physiotherapy practices to suit the patient.

Advocacy for Maintaining Dignity and Independence[edit | edit source]

Autonomy and Decision Making[edit | edit source]

Dementia is a progressive condition which gradually deteriorates the person’s capacity to make some or all decisions in their own best interests. People living with dementia have spent all their lives making decisions to live a full and happy life. During the course of the illness, the person’s reasoning and rationale for important decision becomes compromised and alters from their normal judgements. Legal matters, such as medical and financial decisions, are dealt with early after diagnosis as they hold large risk for the person and others involved. At this point the capacity of the person living with dementia must be determined to allow the appointment of a proxy and the amount of decision making responsibility will be assigned at the time of a choice. There are a few methods of concluding capacity, either through normalized capacity scales or even from what family, friends, and carers find too skewed from normal. The law now states that capacity is not an “all or nothing” approach toward decision making[64]. A diagnosis of dementia does not mean they have lost all competencies, but rather that they have a specific situations that can allow for their capacity to be respected. The situations that are beyond the person’s abilities will fall to the proxy. This decision can be made with the support of the person, their family, friends and carers to determine what is in the best interest of the person living with dementia. Proxies have the difficult and complex problem of understanding how and when to take over the decision making power[64]. This a large responsibility for proxies and there is not much support for them to reach these decision with the best interest in mind and have the ability to follow through with them[65].

There is a push to get early diagnosis as to ascertain the decisions of the person with dementia and their choices of proxy. At this point planning for the future would be simplified and complete.

The Adults with Incapacity (Scotland) Act 2000 (AWI) and the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (MCA) address the rights of people with altered decision-making capacity. Both put in place a legal concept to capacity and the assignment of a competent decision maker and helped throw out the “all or nothing” procedure. The autonomy of the person with dementia will be respected for certain decisions and will always be considered in further choices made by the proxy, power of attorney or guardian once capacity has been determined insufficient. However, anyone making best interest decisions under MCA must also adhere to the principles and, in Scotland, the application of the principles is regarded as good practice for professionals supporting people who may lack some or all capacity but do not have a legally appointed proxy[65][64].

Physiotherapists must be aware of these Acts and what the patient, their family, friends and carers have finalized in terms decision maker. This can guide treatment and goal setting for the best interests of the patient and of course avoid the consequence of an alternative choice made by yourself.

Quality of Life[edit | edit source]

Building a relationship is also key for helping the person and advocating their wishes beyond day to day life. As a physiotherapist we have the responsibility to do the best we can for our patients and guide them into a safe and comfortable future. This demands going above and beyond, especially for those who have conditions as debilitating as dementia. A physiotherapist should try to connect with the patient on a personal level to develop trust, security, independence, worth, equality, communication, respect[66]. These are values which have been found to be the most important to people with dementia and create a sense of normalcy. However, in the fast-paced pressured healthcare system, the time needed to create these relationships can be lost and the patient may not reach their full potential and feel rejected.

Another option to gain information on a patient when those close to them are absent and the patient is unable, is the “getting to know me” package usually supplied in patient notes. The package provides a personal profile of the patient, such as: likes and dislikes, routines, personal history, and communication preferences. This can perhaps speed along visits and allow for some sort of connection to form. The patient is then in a comfortable environment with someone that is familiar with them which allows for a better relationship.

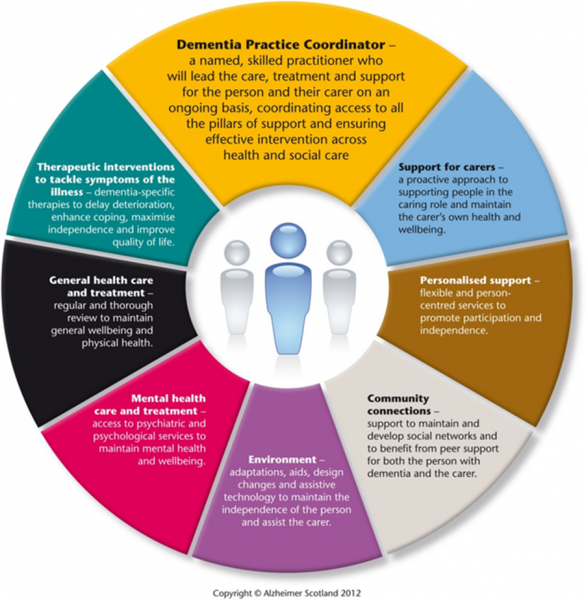

Post Diagnosis Support[edit | edit source]

Long-term care and support is also a responsibility for all healthcare professionals. Post diagnosis support for patients can be tailored to the appropriate stage of life and the wishes of the person living with dementia. Physiotherapists can be involved in commencing the steps towards an appropriate model for aiding their patients and being apart of that model. These pillars of support take into account many of the values of the patient, such as: relationships or someone to talk to; environment; physical health; sense of humour; independence; ability to communicate; sense of personal identity; ability or opportunity to engage in activities; ability to practice faith or religion; and experience of stigma. After building a relationship with a patient we have a better understanding of needs and the ability to advocate for them and people with dementia in general.

Scotland's National Dementia Strategy, as mention before, has developed post diagnostic support models that are provided over an extended period of time to prepare people with dementia and their families and carers with the tools, connections, resources and plans they need to live as well as possible with dementia and prepare for the future[67].

Guarantee for a minimum of one year a named person to work alongside the person, their family and ensure that each person is given help to support and work through the 5 pillars.

The main purpose is to aid the individual and their family to develop their own plan to utilise all their already established supports while building new community connections which will hopefully allow them to stay in their own home as long as possible.

The structured approach to post-diagnostic support, the planning of future care needs and the impact of the 8 Pillars Model will increase the proportion of people being supported in the community[67]. There will be an increase in both the proportion and the number of people with dementia remaining at home.

The 8 Pillars Model can also be modified to accomodate care and support for people with advanced dementia and at end of life with dementia. The structure of the 8 Pillars Model with continue to be used but with the introduction of an Advanced Dementia Specialist Team to provide personalized care[67].

These three models should encompass each post diagostic stage and supply appropriate and substantial support for the person living with dementia. Physiotherapists can play a vital role guiding patients to and be an integral component of the each model.

Clinical Application[edit | edit source]

Through increasing awareness of the condition, educating individuals with dementia, their family, and the wider society, reducing stigmatization, involving and supporting family and carers, ensuring respect for human rights, empowering individuals living with dementia as well as their family and carers, and ensuring the person living with dementia remains at the centre of all conversations regarding treatment and care, physiotherapists have the capability and responsibility to act as advocates for individuals living with dementia.

Watch the video, Barbara's story below, and reflect on the story you see.

Definition of Person-centred Care[edit | edit source]

The philosophy of patient centered care is seeing patients as “equal partners in planning, developing and assessing care to make sure it is most appropriate for their needs” . Person-centered health case system supports people to make informed decisions about and successfully manage their own health and care, including choosing when to let others act on our behalf and deliver care responsive to people’s individual abilities, preferences, lifestyles and goals[69].

The philosophy of patient-centred care is seeing patients as equal partners in planning, developing and assessing care to make sure it is most appropriate for their needs[69].

Generic Principles Underpinning Person-centered Care[edit | edit source]

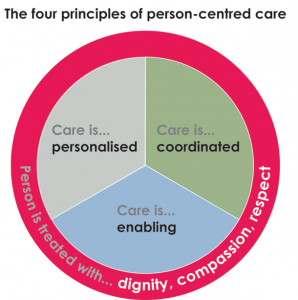

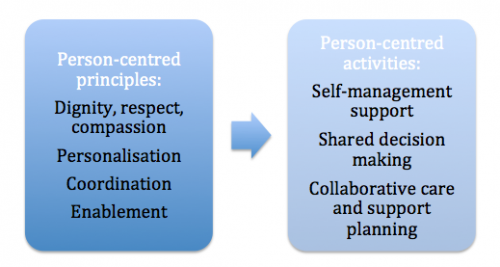

Four generic principles underpinning person-centered care are:[69][70]

- Affording people dignity, respect and compassion.

- Offering coordinated care, support or treatment, so that the person taking care of the patient is task-orientated.

- Offering personalized care, support or treatment with a focus on what matters to the patient. This is why patient’s advocates should be supported to speak on patient’s behalf.

- Being enabling as the system and services should focus on supporting patients to recognize and built upon their own strengths and/or to recover so they can live an independent and fulfilling life.

Implementing the Principles[edit | edit source]

Each person-centred care principle can be carried with a person-centred activity, which are:[69]

- Self-management support with involvement of people to become a resourceful problem-solver,

- Shared decision making and

- Collaborative care and support planning.

In this case both, the self-management support and shared decision making are distinguished by health or social care professionals who make decisions and/or take actions to manage patients’ health and the idea of working in partnership with people and endorse the person-centred principle. By delivering high-quality person-centred care it is important to match those person-centred activities to the appropriate clinical context[69].

Person-centred Care Approach With People Living with Dementia[edit | edit source]

The main factor of person-centred care approach with people living with dementia is seeing the person living with dementia as an individual without focusing on their health condition or on abilities they may have lost. They are considered as a whole person treated with respect and dignity, not just as a collection of symptoms and behaviours to be controlled but seen with individual's unique qualities, abilities, interests, preferences and needs[71]. The first writer who was using a term ‘personhood’ in relation to people living with dementia was Tom Kitwood in his book ‘Dementia reconsidered: The person comes first’ where he defined the term as “a status that is bestowed upon one human being, by others, in the context of relationship and social being, which implies recognition, respect and trust”[72] (p.18).

Indicators for Patient Centred Care Providers For People Living With Dementia - VIPS[edit | edit source]

The person-centred care is consisted of four essential elements, which are summarised with an acronym VIPS[72]. The VIPS model takes into consideration everyone’s behavior towards people living with dementia, valuing them and their carers, individual approach, looking at the world from their perspective and having in mind that the person living with dementia can experience relative well being by positively created social environment and most importantly use this in practice, reflecting on their own work and relationship with person living with dementia.

|

V = Valuing indicators implicate the absolute value of human lives regardless of age or cognitive ability and requires leadership from those responsible for leading the organisation at a senior level[72]. | |

|

Vision |

Does everyone know what we stand for and share the vision? |

|

Management Ethos |

Are management practices empowering to staff delivering direct care to ensure care is person-centred? |

|

Training and practice development |

Are there systems in place to support the development of a workplace skilled in person-centred dementia care? Does staff know that supporting people living with dementia is treated as skilled and important work? |

|

The service environments |

Are there supportive and inclusive physical and social environments for people living with dementia? Do our places help people? |

|

Quality assurance |

Are Continuous Quality Improvement mechanisms in place that are driven by knowing and acting upon needs and concerns of people living with dementia and their supporters? Do we strive to get better all the time? |

|

I = Individual lives indicators encourage an individualised approach. Individualised care aims to recognising uniqueness and requires leadership from those responsible for setting care standards and procedures within the care organisation[72]. | |

|

Individual support and care |

Do our care and support plans promote individual identity showing that everyone is unique, with hopes, fears, strengths and needs? |

|

Regular reviews |

Do we recognise and respond to change? |

|

Personal possessions |

Do people have their favourite and important things around them? Do we know why they are meaningful for them? |

|

Individual preferences |

Are a person’s living with dementia likes and dislikes, preferences and choices listened to, known about and acted upon? |

|

Life stories |

Are a person’s living with dementia important relationships, significant life stories and key events known about and referenced in everyday activities? |

|

Activity and occupation |

Is a person’s living with dementia day full of purpose and engagement with the world regardless of their needs and abilities? |

|

P = Personal perspective indicators help everyone to understand the world from the perspective of the person living with dementia, identified as needing support and requiring leadership from those responsible for day-to-day management and provision of care[72]. | |

|

Communication is key |

We are alert to all the ways that people living with dementia communicate and are we skilled at responding appropriately? |

|

Empathy and acceptable risk |

Do we put ourselves in the position of the person living with dementia we are supporting and think about the world from their point of view? |

|

Physical environment |

Is this place that helps someone living with dementia to feel comfortable, safe and at ease? |

|

Physical health needs |

Are we alert to, responsive to and optimising people’s health and well-being? |

|

Challenging behaviour as communication |

Do we always consider and act on what a person living with dementia is trying to tell us though their behavioural communication? Do we look for underlying reasons rather than seeking to ‘manage’ it? |

|

Advocacy |

Do we speak out on behalf of people living with dementia to make sure their rights, respect and dignity are upheld? |

|

S = Socially supportive environment indicators aim to provide a social environment that supports psychological needs of people living with dementia and also reqire leadership from responsible for day-to-day management and provision of care[72]. | |

|

Inclusion |

Are people living with dementia helped to feel part of what is going on around them and supported to participate in a way that they are able? |

|

Respect |

Does the support we provide show people living with dementia that they are respected as individuals with unique identities, strengths and needs? |

|

Warmth |

Does the atmosphere we create help provide to feel welcomed, wanted and accepted? |

|

Validation |

Are people’s living with dementia emotions and feelings recognised, taken seriously and responded to? |

|

Enabling |

Does the support we provide help people living with dementia to be as active and involved in their lives as possible? |

|

Part of community |

Does our service do all it can to keep people living with dementia connected with their local community and the local community connected with the service? |

|

Relationships |

Do we know about, welcome and involve people who are important to a person living with dementia? |

Developing Partnerships in Practice – Person-centred Care[edit | edit source]

Delivering patient-centred care is one way in which physiotherapists can advocate for their patients. Patient-centred care involves respecting the patient’s values and beliefs, involves informed and shared decision-making between the patient, family and health professionals, as well as enabling the patient and family to have choice in the care they receive[73]. As such, patient-centred care involves respect for the patient’s human rights, which as an advocate, physiotherapists can ensure they uphold.

Developing partnerships between individuals living with dementia, their family and carers, health and social care professionals and the wider society is key for successful person-centred care. It is an interactive process that demands mutual exchange of knowledge with all parties expecting and receiving respect and understanding. Partnerships in dementia care are constructed through use of language, maintaining personhood by removing negative and stigmatizing attitudes and fostering a sense of identity and worth through honesty, empowerment, encouragement, acceptance and inclusion[74]. Through advocacy, physiotherapists can take an active role in creating these crucial partnerships.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Guidelines (NICE)[75] on supporting people with dementia state the principles of person-centred care are the foundation of best practice in dementia care. The fourth principle highlights “the importance of relationships and interactions…and their potential for promoting well-being”. Supporting and enhancing family and carer input and their relationship with the individual living with dementia is a way physiotherapists can enhance person-centred care and accordingly use their role of advocate to increase the well-being of individuals living with dementia.

Keeping in mind elements as guiding principles for physiotherapists, physiotherapy students and/or other health care professionals could use reflective questions to reflect on their interactions with people living with dementia and their families or as an advocate[75][72].

Reflective questions include:

- Was I treating person living with dementia as an unique individual with a history and a wide range of strengths and needs?

- Did my behaviour and interactions help this person living with dementia to feel socially confident and that they are not alone?

- Was I making a serious attempt to see my actions from the perspective of the person living with dementia I am trying to help? How did this person interpret my actions?

- Did my behaviour and the manner in which I was communicating with the person living with dementia show that I respect, value and honour them?

|

Maya Angelou |

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

Advocacy is vital when working with individuals with dementia. The challenges faced by this population show that they require advocates to uphold their rights and ensure they receive person centered appropriate care. Physiotherapists possess the skills, attitudes and beliefs required to be successful advocates.

Resources[edit | edit source]

If you would like to further your knowledge surrounding this topic, please visit the sites below.

- https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents.php?categoryID=200306 -A compressive educational resource for professionals working with individuals living with dementia.

- http://www.siaa.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/siaa_principles_and_standards_2010.pdf - A source from the Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliance to further develop your role as an advocate

- HCPC Standards of proficiency: Physiotherapists -

http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10000DBCStandards_of_Proficiency_Physiotherapists.pdf - CSP’s Physiotherapy Framework -

http://www.csp.org.uk/documents/physiotherapy-framework-condensed-version - HCPC Standards of conduct, performance and ethics -

http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10002367FINALcopyofSCPEJuly2008.pdf

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ WHO. Governments commit to advancements in dementia care. Available from: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2015/action-on-dementia/en/ (accessed 1 May 2019).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Scottish Government. Proposal for Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy 2016-19. Available from: https://www.gov.scot/Resource/0049/00497716.pdf [Accessed 1 May 2019].

- ↑ AlzheimersResearch UK. Alzheimer’s Research UK presents #sharetheorange. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9MvEZskR6o [last accessed 1/05/2019]

- ↑ Allen RE. The New Penguin English Dictionary. 3rd ed. London: Penguin Books; 2003. Advocacy; p43

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Campagna KD. Who will be the patient advocate on a multidisciplinary team? Hospital Pharmacy Journal. 2013;48(2):90-92.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Bateman N. Advocacy Skills for Health and Social Care Professionals. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers Ltd; 2000.

- ↑ Centacare. Catholic Diocese of Rockhampton. Guidelines for Advocacy. Available from: https://www.centacare.net/downloads/forms/Guidelines_for_Advocacy.pdf (accessed 1 November 2016)

- ↑ Kelland K, Hoe E, McGuire MJ, Yu J, Andreoli A, Nixon SA. Excelling in the role of advocate: a qualitative study exploring advocacy as an essential physiotherapy competency. Physiotherapy Canada. 2014;66(1):74-80.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 CSP. Physiotherapy framework (condensed version). 2013. Available from: http://www.csp.org.uk/documents/physiotherapy-framework-condensed-version. (accessed 2 November 2016)

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Health and Care Professions Council. Standards of conduct, performance and ethics. Available from: http://www.hcpc-uk.co.uk/assets/documents/10004EDFStandardsofconduct,performanceandethics.pdf (accessed 30 October 2016)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 Health and Care Professions Council. Standards of proficiency: physiotherapists. Available from: http://www.hpc-uk.org/assets/documents/10000DBCStandards_of_Proficiency_Physiotherapists.pdf (accessed 31 October 2016)

- ↑ Scottish Independent Advocacy Alliance. Providing advocacy. Available from: http://www.siaa.org.uk/us/independent-advocacy/providing-advocacy/. (accessed 1 May 2019)

- ↑ Alzheimer’s Society. Dementia 2014: Opportunity for change. Available from: Ahttps://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=2317. (accessed 7 November 2016)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Lewis F, Schaffer SK, Sussex J, O’Neill P, Cockcroft L. The trajectory of dementia in the UK – Making a difference. Office of Health Economics 2014. Available from: http://www.alzheimersresearchuk.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/OHE-report-Full.pdf ([Accessed 1 May 2019].

- ↑ Prince M, Wimo A, Guerchet M, Ali G-C, Wu Y-T, Prina M. World Alzheimer’s Report 2015, the global impact of dementia: an analysis of prevalence, incidence, costs and trends. Available from: https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2015 (accessed 1 May 2019).

- ↑ Werner P, Stein-Shvachman I, Korczyn AD. Early onset dementia: clinical and social aspects. International Psychogeriatrics. 2009; 21(4):631-636.

- ↑ Dementia UK. About Dementia. Available from:https://www.dementiauk.org/understanding-dementia/about-dementia/ (accessed 1 May 2019).

- ↑ AlzheimersResearch UK. A Walk Through Dementia - Launch film. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nW1Y3Fnv7Mw [last accessed 1/05/2019]

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Alzheimer’s Society. Counting the cost: Caring for people with dementia on hospital wards. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=356fckLR (accessed 7 November 2016)

- ↑ CSP. Physiotherapy works: Dementia Care. http://www.csp.org.uk/professional-union/practice/evidence-base/physiotherapy-works/dementia-care (accessed 1 May 2019).

- ↑ Cerga-Pashoja A, Lowery D, Bhattacharya R, Griffin M, Iliffe S, Lee J et al. Evaluation of exercise on individuals with dementia and their carers: A randomized controlled trial. Trials 2010; 11(53): 1-7. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-11-53

- ↑ Lawlor, B. Managing behavioral and psychological symptoms in dementia. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;181(6):463-465.

- ↑ Oddy R. Promoting mobility for people with dementia: a problem-solving approach. 3rd ed. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2011.

- ↑ Christofoletti G, Oliani MM, Gobbi S, Stella F, Bucken Gobbi, LT, Renato Canineu P. A controlled clinical trial on the effects of motor intervention on balance and cognition in institutionalized elderly patients with dementia. Clinical Rehabilitation. 2008; 22(7), 618–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/026921550708623

- ↑ Williamson T. Dementia: Out of the shadows. Alzheimer's Society; 2008.

- ↑ Graham N, Lindesay J, Katona C, Bertolote JM, Camus V, Copeland JR et al. Reducing stigma and discrimination against older people with mental disorders: a technical consensus statement. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2003;18(8):670-8.

- ↑ ErvingGoffman S. Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Pren-tice-Hall. 1963.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Victor C. The social context of ageing: A textbook of gerontology. Routledge; 2004 Dec 20.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Lee M. Promoting mental health and well-being in later life. London: Age Concerns and Mental Health Foundation. 2006. Available from:https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/promoting_mh_wb_later_life.pdf (accessed 2 May 2019)

- ↑ Godfrey M, Surr C, Boyle G, Townsend G, Brooker D. Prevention and service provision: Mental health problems in later life. 2005.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Batsch NL, Mittelman MS. World Alzheimer Report 2012. Overcoming the Stigma of Dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), London; 2012. Available from:https://www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2012 (accessed 2 May 2019)

- ↑ Abrams D. How Ageist is Britain?- Age discrimination. London: Age Concern; 2005. Available from:https://kar.kent.ac.uk/24312/1/HOWAGE~1.PDF (accessed 2 May 2019)

- ↑ Milne A, Williams J. Meeting the mental health needs of older women: taking social inequality into account. Ageing and Society. 2000;20(06):699-723.

- ↑ Milne A. The ‘D’word: Reflections on the relationship between stigma, discrimination and dementia. Journal of Mental Health. 2010;19(3):227-33.

- ↑ Lakey L. Counting the cost: caring for people with dementia on hospital wards. London: Alzheimer’s Society. 2009.

- ↑ Milne A, Peet J. Challenges & resolutions to psycho-social well-being for people in receipt of a diagnosis of dementia: A literature review. London: Alzheimer’s Society, 2008.

- ↑ Livingston G, Cooper C, Woods J, Milne A, Katona C. Successful ageing in adversity: the LASER–AD longitudinal study. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 2008;79(6):641-5.

- ↑ Kissel EC, Carpenter BD. It's all in the details: Physician variability in disclosing a dementia diagnosis. Aging and Mental Health. 2007;11(3):273-80.

- ↑ The Scottish Government. Age demographics. Available from: http://www.gov.scot/Topics/People/Equality/Equalities/DataGrid/Age/AgePopMig [Accessed 18 November 2016].

- ↑ Office of the Deputy Prime Minister, London. Unit Social Exclusion. A sure start to later life. 2006. Available from:http://www.cpa.org.uk/cpa/seu_final_report.pdf [Accessed 2 May 2019]

- ↑ Scotland Legislation. The Equality Act 2010. Available from: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2010/15/contents [Accessed 2 May 2019]

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Department of Health. Living well with dementia: A national dementia strategy. London: COI for Department of Health. 2009.

- ↑ Mental Capacity Act 2005. Code of practice. Department for Constitutional Affairs. London:TSO, 2007.

- ↑ Alzheimer’s Society. 2015. Equality, discrimination and human rights. Availablee from:https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/documents_info.php?documentID=1674 (accessed 17 November 2016).

- ↑ Alzheimer’s Society. 2014. Dementia UK: second edition. Available from:https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=1491 (accessed 17 November 2016).

- ↑ Alzheimer’s Scotland. APPG 2013 BAME report. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=1186 (accessed 23 November 2016).

- ↑ 47.0 47.1 47.2 47.3 Alzheimer’s Scotland. 2016. A Human Rights-Based Approach. Available from: http://www.alzscot.org/campaigning/rights_based_approach (accessed 3 November 2016).

- ↑ All Party Parliamentary Group on Dementia. Dementia does not discriminate. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?downloadID=1186 (accessed 2 November 2016).

- ↑ Dowrick A, Southern A. Dementia 2014: opportunity for change. Alzheimer's Society; 2014. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/dementia_2014_opportunity_for_change.pdf (accessed 2 May 2019)

- ↑ Knapp M, Prince M, Albanese E, Banerjee S, Dhanasiri S, Fernandez JL. Dementia UK: The full report. 2007. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/News_and_Campaigns/Campaigning/PDF/Dementia_UK_Full_Re (accessed 20 November 2016)

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy 2013-2016. 2016.Available from: https://www.scotland.gov.uk/Topics/Health/Services/Mental-Health/Dementia [Accessed 16 November 2016].

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 Standards of care for dementia in Scotland. Action to support the change programme, Scotland’s National Dementia Strategy. Available from: http://www.gov.scot/resource/doc/350188/0117212.pdf (accessed 24 Novemer 2016).

- ↑ Scottish Government. Promoting Excellence: A framework for all health and social services staff working with people with dementia, their families and carers; 2011. Available from: http://www.scotland.gov.uk/Resource/Doc/350174/0117211.pdf (accessed 31 October 2016).

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Alzheimers Society. Public awareness of dementia: what every commissioner needs to know. London: Alzheimers Society, 2009. Available from:https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/sites/default/files/migrate/downloads/dementia_what_every_commissioner_needs_to_know.pdf (accessed 2 May 2019)

- ↑ Bond J, Stave C, Sganga A, Vincenzino O, O'Connell B, Stanley RL. Inequalities in dementia care across Europe: key findings of the Facing Dementia Survey. International Journal of Clinical Practice 2005; 59:146:8–14.

- ↑ Alzheimers Disease International. World Alzheimer report: Overcoming the stigma of dementia. Available from: http://www.alz.org/documents_custom/world_report_2012_final.pdf (accessed 23 October 2016).

- ↑ Sarang K, Kerry A, Kaarin J. A qualitative study of older and middle-aged adults' perception and attitudes towards dementia and dementia risk reduction. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2015; 71(7):1694-1703.

- ↑ Innes A, Kelly F, McCabe L, editors. Key Issues in Evolving Dementia Care: International Theory-based Policy and Practice.London: Jessica Kingsley, 2012.

- ↑ The Dementia Engagement and Empowerment Project Guide. Dementia words matter: Guidelines on language about dementia: Liverpool, 2014. Available from :http://dementiavoices.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/DEEP-Guide-Language.pdf (accessed 2 May 2019)

- ↑ Alzheimer’s Australia. Dementia Language Guidelines; 2015. Available from: https://fightdementia.org.au/sites/default/files/full-language-guidelines.pdf (accessed 21 October 2016).

- ↑ Cowdell F. The care of older people with dementia in acute hospitals. International Journal of Older People’s Nursing. 2010; 5:2: 83–92.

- ↑ Douglas-Dunbar M, Gardiner P. Support for carers of people with dementia during hospital admission. Nursing Older People. 2007;19:8: 27–30.

- ↑ Galvin JE, Kuntemeier B, Al-hammadi N, Germino J, Murphy-White M, Mcgillick J. ‘Dementia friendly hospitals: Care not crisis.’ An educational program designed to improve the care of the hospitalized patient with dementia. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders 2010;24:4:372–379.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Alzheimer Scotland. Dementia: autonomy and decision-making. Alzheimer Scotland; 2012. Available from: https://www.alzscot.org/assets/0000/5332/dementia-autonomy-decision-making-ResearchReport.pdf (accessed 2 May 2019)

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Thompson D. Dementia. Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE). Making decisions in a person’s best interests - dementia; 2014 Available from: https://www.scie.org.uk/dementia/supporting-people-with-dementia/decisions/best-interest.asp. (accessed 14 November 2016).

- ↑ Ericsson I, Kjellstrom S, Hellstrom I. Creating relationships with persons with moderate to severe dementia. Dementia. 2013;12(1):63–79.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 67.2 Scotland A. 8 pillars model of community support - campaigning - Alzheimer Scotland; 2016. Available from: http://www.alzscot.org/campaigning/eight_pillars_model_of_community_support. (accessed 14 November 2016]

- ↑ Sawnsea Bay NHS TV. Barbara's Story. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VFXirEnjfTI [last accessed 2/05/2019]

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 69.4 Collins A. Measuring what really matters.Available from: http://www.health.org.uk/sites/health/files/MeasuringWhatReallyMatters.pdf (accessed 5 November 2016).

- ↑ The Health Foundation. What is person-centred care.Available from:http://personcentredcare.health.org.uk/overview-of-person-centred-care/what-person-centred-care (accessed 5 Nov 2016).

- ↑ Alzheimer’s Society. Factsheet: Selecting a care home. Available from: https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/site/scripts/download_info.php?fileID=1787 (accessed 5 November 2016).