Physiological Changes in Pregnancy

Original Editor - Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher

Top Contributors - Esraa Mohamed Abdullzaher, Safiya Naz, Khloud Shreif, Kim Jackson, Rosie Swift, Vidya Acharya and Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Pregnancy and its changes is a normal physiological process that happens in all mammalian in response to the development of the fetus. These changes happen in response to many factors; hormonal changes, increase in the total blood volume, weight gain, and increase in fetus size. All these factors have a physiological impact on all systems of the pregnant woman; musculoskeletal, endocrine, reproductive system, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal system, and renal changes. The full pregnancy period is about 40 weeks when the delivery happens before 37 weeks it is called a premature baby.

Anatomy Background[edit | edit source]

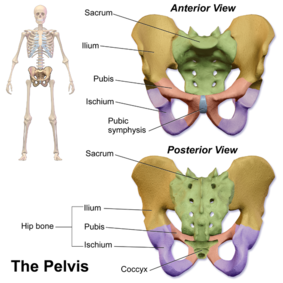

- The pelvis is the region found between the trunk and lower limbs.

- In females, the pelvis is wider and lower than that of their male counterpart, making it more suited to accommodate a fetus during both pregnancy and delivery[1].

- It protects and supports the pelvic contents, provides muscle attachment and facilitates the transfer of weight from trunk to legs in standing, and to the ischial tuberosities in sitting.

- The cross-sectional anatomy of the female pelvis shows five bones: two hip bones, sacrum, coccyx, and two femurs.[1] The joints are supported by some of the strongest ligaments in the body which become laxer during pregnancy leading to increased joint mobility and less efficient load transfer through the pelvis.

- The pelvic outlet at the base of the pelvis is narrower in its transverse diameter when compared with the pelvic inlet; it comprises the pubic arch, ischial spines, sacrotuberous ligaments, and coccyx.[2]

- Four pairs of abdominal muscles combine to form the anterior and lateral abdominal wall and may be termed the abdominal corset.

- Transversus abdominis lies deep to the internal abdominal oblique and external abdominal oblique with the rectus abdominis central, anterior and superficial abdominal oblique, external oblique and transversus abdominis insert into an aponeurosis joining in the midline at the linea alba. The deep abdominal muscles, together with the pelvic floor muscles, multifidus, and diaphragm, can be considered as a complete unit and may be termed the lumbopelvic cylinder. This provides support for the abdominal contents and maintains intraabdominal pressure.[2]

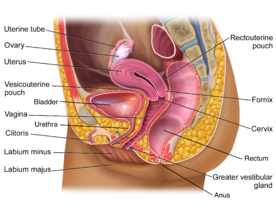

- Organs of the female reproductive system present in the pelvis are subdivided into internal and external genitalia.

- The internal genitalia consists of the uterus, two uterine tubes, two ovaries, and the vagina.

- The external genitalia mainly consists of the mons pubis, clitoris, labia majors, labia minora, and Bartholin glands.[1]

Endocrine System Changes[edit | edit source]

Pregnancy is a normal physiological process and is associated with changes in hormone levels, one of these hormones called steroid hormones including progesterone and estrogen they are important during pregnancy to save fetus delivery and maintenance of pregnancy stable[3]. Its levels increase gradually with pregnancy progression, unlike relaxin reaches the highest level at first trimester then decrease at the end of pregnancy. All steroids/ sex hormones produced from the placenta during pregnancy but the progesterone is the chief one.

Progesterone at the beginning is produced by corpus luteum and reaches its maximum at 10 weeks then declined gradually and the placenta starts to produce the progesterone reaching its maximum amount at 40 weeks, the placenta production of progesterone is decreased in the last month. It is important to prevent premature uterine contractions, reduces the tone of smooth muscles causing constipation due to the water retention in the colon, decrease the tone of uterine and detrusor muscles, participate in the development of mammary glands and increase the storage of fat due to its catabolic effect on metabolism.

Estrogen, like progesterone, its production starts at corpus luteum then the placenta takes the function to produce estrogen, reaching its peak at the date of birth. Estrogen has a vasodilation effect, increases blood flow to uteroplacental in preparing for uterine contraction. In addition to its catabolic effect and its role for the development of the mammary gland, estrogen increases water retention and maybe a receptor site for relaxin.

Relaxin is produced in the corpus luteum and later in the decidua and placenta, increases in the first trimester. it has a strong vasodilator effect, an effect on hemodynamic and affects kidney function[4], and effects on pelvic floor muscle relaxation.

Reproductive System Changes[edit | edit source]

- During pregnancy, the internal genital tract/ reproductive systems undergone anatomical and physiological changes to accommodate the changes and development of the fetus.

- These changes presented as below:

Uterus[edit | edit source]

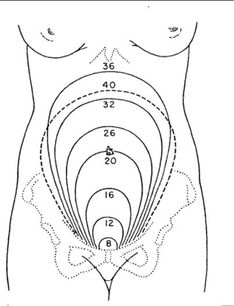

- With pregnancy progression, the uterus leaves the pelvic and ascends to the abdominal cavity

- The abdominal content displaced in response to the increased size of the uterus which is five times more than normal

- This increases in the size of uterus associated with an increase of blood supply to the uterus and uterine muscle activity,

- Uterus increases in size till the 38 weeks after that the funds level starts to descend preparing for delivery.

- Its weight increases from 50mg to 1000mg after that it doesn't get heavier any more and only stretches to accommodate the fetus size, and associated with an increase in the thickness and length of the fundus.

Cervix[edit | edit source]

The enlarged mucus glands of the cervix during pregnancy secretes a mucus plug called “operculum”, act as a seal for the uterus and protect it from ascending infection, and act as a barrier between the vagina and cervix. Later in pregnancy before delivery, there is a softening of the cervix in response to the increasing uterine contractions.

Vagina[edit | edit source]

During pregnancy there is an increase in the blood supply to the vagina, its colour change from pink to purple, and becomes more elastic in the second trimester[5][6].[edit | edit source]

Musculoskeletal Changes[edit | edit source]

Postural Changes[edit | edit source]

- The overall equilibrium of the spine and pelvis alters as the pregnancy progresses[7]

- There is still confusion as to the exact nature of any associated postural adaptation. With weight gain, increased blood volume, and ventral growth of the fetus,

- The centre of gravity no longer falls over the feet, increase in anteroposterior and medial-lateral sway[8], and women may need to lean backwards to gain equilibrium resulting in disorganisation of spinal curves.

- Reported postures include a reduction in lumbar lordosis an increase in both lumbar lordosis and thoracic kyphosis or a flattening of the thoracolumbar spinal curve.

- There will be compensatory changes to posture in the thoracic and cervical spines, and this combined with the extra weight of the breasts may result in posterior displacement of the shoulders and thoracic spine, increase anterior pelvic tilting, and increase of the cervical lordosis.[2]

- These changes may be still similar for 8 weeks after delivery.

Articular Changes[edit | edit source]

- Altered levels of relaxin, oestrogen, and progesterone during pregnancy result in an alteration to collagen metabolism, this laxity is due to the break down of collagen in the targeted tissue and replaces it by a modified form that contains higher water content.

- That increases connective tissue pliability and extensibility. Therefore, ligamentous tissues are predisposed to laxity with resultant reduced passive joint stability, ligament laxity reaches its maximum at the second trimester[9].

- The symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joints are particularly affected to allow for the birth of the baby. Ligamentous laxity may continue for six months postpartum. Biomechanical changes of the spinal and pelvic joints may involve an increase in sacral promontory, an increase in lumbosacral angle, a forward rotatory movement of the innominate bones, and downward and forward rotation of the symphysis pubis.

- The normal pubic symphyseal gap of 4–5 mm shows an average increase of 3 mm during pregnancy

- Pelvic joint loosening begins around 10 weeks, with maximum loosening near term. Joints should return to normal at 4–12 weeks postpartum.

- The sacrococcygeal joints also loosen. By the last trimester, the hip abductors, extensors, and the ankle plantar flexors increase their net power during gait and there is an increase in load on the hip joints of 2.8 times the normal value when standing and working in front of a worktop. As the uterus rises in the abdomen the rib cage is forced laterally and the diameter of the chest may increase by 10–15 cm.[2]

Neuromuscular Changes[edit | edit source]

- During pregnancy, the enlarged uterus results in elongation of the abdominal muscles and separation of the linea alba.

- Passive joint instability (as seen in pregnancy) alters afferent input from joint mechanoreceptors and probably affects motor neuron recruitment.

- A decrease in muscle stiffness and thus active stability of joints may result from alteration of muscle spindle regulation and this is applicable particularly to muscles around the pelvic girdle.

- These changes may lead to poor recruitment of the muscles responsible for pelvic girdle stability (particularly gluteus medius and Maximus) and result in decreased tension of these muscles during walking, perhaps resulting in pelvic girdle pain (PGP).[2]

Cardiovascular changes[edit | edit source]

- The heart adapts to the increased cardiac demand that occurs during pregnancy in many ways.

- Cardiac output increases throughout early pregnancy, and peaks in the third trimester, usually to 30-50% above baseline.

- Estrogen mediates this rise in cardiac output by increasing the pre-load and stroke volume, mainly via a higher overall blood volume (which increases by 40–50%).

- The heart rate increases, but generally not above 100 beats/ minute.

- Total systematic vascular resistance decreases by 20% secondary to the vasodilatory effect of progesterone. Overall, the systolic and diastolic blood pressure drops 10–15 mm Hg in the first trimester and then returns to the baseline in the second half of pregnancy.

- All of these cardiovascular adaptations can lead to common complaints, such as palpitations, decreased exercise tolerance, and dizziness.[10]

Respiratory Changes[edit | edit source]

- Respiratory changes during pregnancy are important to accommodate and meet the demands of mother and fetus, there are changes in all lung volumes, changes in the upper airway respiratory tract, and breathing pattern.

- There is increasing oedema in the upper airway tract, which in this case, smaller endotracheal tube when intubation is necessary intervention will be needed. Elevated diaphragm for about 4cm is a clinical presentation with pregnant women because of the enlarged uterus.

- Ligaments connecting ribs to sternum like other ligaments that affected by relaxin and progesterone hormones and become lax during pregnancy, so the subcostal angel and chest circumference increase from 5-7cm and this is associated with lower chest compliance.

- Lung Volumes change as follows; functional residual capacity decreases by 10-25%, expiratory reserve volume 15-20%, and residual volume decreased by 20-25%, and the total lung capacity decrease. In addition, an increase in the respiratory capacity by 5-10%, respiratory rate by 1-2 breaths more than normal, and an increase in the tidal volume 30-50%.

- We will find an increase in oxygen consumption by 30% and the metabolic rate by 15% in pregnant women, but they still have a lower oxygen reservoir due to the lower rate of functional residual capacity FRC, and are more prone to hypoxic, hyperventilation and dyspnea are common in pregnancy.

- In addition these changes there is an increase in PaO2 to facilitate the transfer of oxygen from mother to fetus and lower PaCo2 to facilitate the transfers of carbon dioxide from fetus to mother[11][4].

Gastrointestinal changes[edit | edit source]

- Progesterone causes smooth muscle relaxation which slows down GI motility and decreases lower oesophagal sphincter (LES) tone.

- The resulting increase in intragastric pressure combined with lower LES tone leads to the gastroesophageal reflux commonly experienced during pregnancy.

- Nausea and vomiting of pregnancy, commonly known as “morning sickness”, is one of the most common GI symptoms of pregnancy. It begins between the 4 and 8 weeks of pregnancy and usually subsides by 14 to 16 weeks.

- The exact cause of nausea is not fully understood but it correlates with the rise in the levels of human chorionic gonadotropin, progesterone, and the resulting relaxation of the smooth muscle of the stomach[12]. also, constipation and haemorrhoids can occur during pregnancy.

Renal changes[edit | edit source]

- A pregnant woman may experience an increase in the size of the kidneys and ureter due to the increased blood volume and vasculature.

- Later in pregnancy, the woman might develop physiological hydronephrosis and hydroureteronephrosis, which are normal.

- There is an increase in glomerular filtration rate associated with an increase in creatinine clearance, protein, albumin excretion, and urinary glucose excretion.

- There is also an increase in sodium retention from the renal tube so oedema and water retention is a common sign in pregnant women[11].

- In the third trimester when the fetus starts to engage in the pelvis, there is an increased frequency of urination, incontinence.

Nutrition[edit | edit source]

- During pregnancy, both protein metabolism and carbohydrate metabolism are affected.

- One kilogram of extra protein is deposited, with half going to the fetus and placenta, and another half going to uterine contractile proteins, breast glandular tissue, plasma protein, and haemoglobin.

- An increased requirement for nutrients is given by fetal growth and fat deposition.

- Changes are caused by steroid hormones, lactogen, and cortisol.

- Pregnant women require a caloric increase. also there's a weight gain of 20 to 30 lb (9.1 to 13.6 kg).[13]

Problems may have during pregnancy[edit | edit source]

- Pelvic floor dysfunction.

- Rib pain.

- Nerve compression syndromes.

- Carpal tunnel syndrome.

- Muscle cramps.

- Symphysis pubis dysfunction

- Morning sickness.

- Edema.

- Pre-eclampsia

- Back pain.

Exercises And Contraindications For It[edit | edit source]

For regular exercisers Consult your doctor or midwife before beginning exercise.

Exercise at a moderate level most days for 30 minutes or more also discontinue contact sports and activities which carry a high risk of falling or abdominal trauma, avoid scuba diving.

Self regulate both the level of intensity and duration of exercise, aiming to keep the core temperature below 38°C. and aim for low impact activity..Wear suitably supportive footwear to reduce musculoskeletal stresses. Maintain adequate fluid intake to prevent dehydration, and avoid exercise during hot and humid weather, or with pyrexia. Warmup and cooldown for at least five minutes. Do not use developmental stretching (because of the effects of relaxin). Brisk walking has fewer risk of falling.

Seek professional advice on specific exercises (e.g. for the pelvic floor muscles). Avoid ballistic exercise, low squats, crossover steps, and rapid changes of direction. Do not exercise in supine after 16 weeks gestation, to avoid aortocaval compression. Eat to appetite, without calorific restriction. Work towards crosstraining to avoid overtraining, and stop exercise before fatigue sets in.

In addition to the above, women not used to regular exercise should be advised:

not to start an exercise programme until >13 weeks gestation; to consider beginning with nonweightbearing exercises, such as aquanatal classes; to progress from simple and basic levels of exercise, increasing exercise tolerance gradually, under the supervision of a suitably qualified professional.

Contraindications :

- Cardiovascular

- Respiratory

- Renal or thyroid disease

- Diabetes (type 1, if poorly controlled)

- The history of miscarriage, premature labour, et al growth restriction,

- Cervical incompetence;

- Hypertension,

- Vaginal bleeding,

- Reduced fetal movement,

- Anaemia,

- Breech presentation,

- Placenta praevia.[2]

All women should stop exercising immediately and seek advice from a doctor if they experience: abdominal pain. vaginal bleeding.shortness of breath, dizziness, faintness, persistent severe headache, palpitations or tachycardia; PGP, which may also lead to difficulty in walking.

See also[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Kenhub.Female pelvis .Avalaible from:https://www.kenhub.com/en/start/c/female-pelvis

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Stuart Porter,Tidy's physiotherapy.1991

- ↑ Brunton PJ, Russell JA. Endocrine induced changes in brain function during pregnancy. Brain research. 2010 Dec 10;1364:198-215.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Kohlhepp LM, Hollerich G, Vo L, Hofmann-Kiefer K, Rehm M, Louwen F, Zacharowski K, Weber CF. Physiological changes during pregnancy. Der Anaesthesist. 2018 May;67(5):383-96.

- ↑ Obstetric and Newborn Care.Changes of the Reproductive System during Pregnancy. Available from:https://brooksidepress.org/ob_newborn_care_1/?page_id=331&cn-reloaded=1

- ↑ Open.edu.Antenatal Care Module: 7. Physiological Changes During Pregnancy.Available from: https://www.open.edu/openlearncreate/mod/oucontent/view.php?id=37&printable=1

- ↑ Inanir A, Cakmak B, Hisim Y, Demirturk F. Evaluation of postural equilibrium and fall risk during pregnancy. Gait & Posture. 2014 Apr 1;39(4):1122-5.

- ↑ Danna-Dos-Santos A, Magalhaes AT, Silva BA, Duarte BS, Barros GL, Maria De Fátima CS, Silva CS, Mohapatra S, Degani AM, Cardoso VS. Upright balance control strategies during pregnancy. Gait & posture. 2018 Oct 1;66:7-12.

- ↑ Cherni Y, Desseauve D, Decatoire A, Veit-Rubinc N, Begon M, Pierre F, Fradet L. Evaluation of ligament laxity during pregnancy. Journal of gynecology obstetrics and human reproduction. 2019 May 1;48(5):351-7.

- ↑ Sanghavi M, Rutherford JD. Cardiovascular physiology of pregnancy. Circulation. 2014 Sep 16;130(12):1003-8.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Tan EK, Tan EL. Alterations in physiology and anatomy during pregnancy. Best practice & research Clinical obstetrics & gynaecology. 2013 Dec 1;27(6):791-802.

- ↑ Gomes CF, Sousa M, Lourenço I, Martins D, Torres J. Gastrointestinal diseases during pregnancy: what does the gastroenterologist need to know?. Annals of gastroenterology. 2018 Jul;31(4):385.

- ↑ Forbes LE, Graham JE, Berglund C, Bell RC. Dietary change during pregnancy and women’s reasons for change. Nutrients. 2018 Aug;10(8):1032.