Physical Activity Guidelines for Spinal Cord Injury

Original Editor - Naomi O'Reilly

Top Contributors - Naomi O'Reilly, Ewa Jaraczewska, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Jess Bell, Wanda van Niekerk, Merinda Rodseth and Admin

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Physical activity is an essential part of a healthy lifestyle for adults with spinal cord injury. While it is acknowledged that exercise is an important tool for improving wellbeing and enhancing independence for individuals with a spinal cord injury, many health and fitness professionals highlighted a lack of clear guidance on how best to prescribe physical activity for this population group.

The World Health Organisation developed Global Recommendations on Physical Activity for Health with the overall aim of providing national and regional level policy makers with guidance on the dose-response relationship between the frequency, duration, intensity, type and the total amount of physical activity needed for the prevention of Non-Communicable Diseases. While the World Health Organization suggested that these recommendations could be applied to adults with disabilities with adjustment to the guidelines for each individual based on their exercise capacity and specific health risks or limitations, these recommendations were not specifically tailored to the spinal cord injury population. [1]

Development of Scientific Guidelines[edit | edit source]

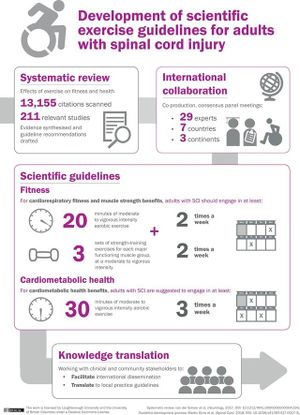

The guidelines were developed in partnership with key stakeholders using a rigorous, systematic, participatory process, that followed the gold-standard approach for formulating clinical practice guidelines. The team, collaborating with an international panel of researchers, clinicians, community organisations, adults with a spinal cord injury, and knowledge translation specialists, jointly devised a set of exercise guidelines which were launched at the International Spinal Cord Society Annual Meeting in 2017.

Translating Scientific Guidelines to Practice Guidelines[edit | edit source]

Rigorous and systematic consumer engagement incorporating patient-public involvement is a vital part of the process of translating scientific guidelines into working guidelines understandable by those they are designed by before widespread dissemination. Engagement of individuals with a spinal cord injury and other key stakeholder groups to determine the best way to present the guidelines including the development of resources to facilitate understanding, uptake and implementation of the guidelines.[4]Spinal Cord Injury Exercise Guidelines[edit | edit source]

The exercise guidelines provide minimum thresholds for achieving cardiorespiratory fitness and muscle strength and improved cardiometabolic health. The guidelines should be achieved above and beyond the incidental physical activity, one might accumulate in the course of daily living, through routine participation in exercise modalities and cotexts that are sustainable, enjoyable, and safe.[4][6] For those already not already exercising, start with smaller amounts of exercise and gradually increase the duration, frequency and intensity, as a progression towards meeting the guidelines, recognising that exercise below the recommended levels may or may not bring small changes in cardiorespiratory fitness or cardiometabolic health.[6]

Who do they apply to[edit | edit source]

Men and women aged 18 - 64 with a chronic traumatic or non-traumatic Spinal Cord Injury > 12 months post-onset, with a neurological level C3 or lower including tetraplegia and paraplegia, irrespective of race, ethnicity or socio-economic status, who are not active above and beyond daily activities. [6]

While there is currently insufficient scientific evidence to draw firm conclusions about the risks and benefits of these guidelines for individuals with a Spinal Cord Injury < 12 months post-onset, aged 65 years or older, and those with co-morbid conditions, they may be appropriate following consultation with a health care provider prior to beginning an exercise program. [6]

What settings do they apply to[edit | edit source]

Physical activity as we know can occur in a range of venues, indoors and outdoors, in all sorts of weather. The Spinal Cord Injury Exercise Guidelines are meant to be applicable to exercise and physical activity performed in a wide range of settings, which include but not limited to; [6]

Rehabilitation settings

Fitness centers

Individuals' own homes

Cardiorespiratory fitness and muscle strength[edit | edit source]

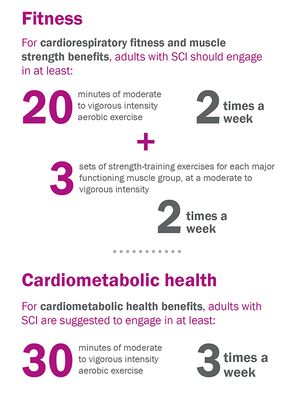

This guideline reflects the minimum frequency, intensity, and duration of exercise involving combined upper-body aerobic plus strength exercise yielding significant improvements in fitness outcomes and affirms the 2011 Spinal Cord Injury Physical Activity Guidelines, but has also been updated to align with the evidence base by referring to ‘exercise’ rather than ‘physical activity’. To improve cardiorespiratory fitness and muscle strength, adults with a spinal cord injury should engage in at least;

20 Min of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise, 2 times per week, and

3 Sets of strength exercises for each major functioning muscle group, at a moderate-vigorous intensity, 2 times per week

Cardiometabolic health[edit | edit source]

Cardiometabolic disease, which includes a spectrum of conditions from insulin resistance, progressing to the metabolic syndrome, pre-diabetes, and finally to more severe conditions including Cardiovascular Disease and Type 2 Diabetes, currently poses a serious health and economic burden worldwide, with prevalence predicted to increase. Independent risk factors include prolonged sitting, lack of physical activity, poor diet, and short sleep duration, which have all become commonplace worldwide. [7]

This guideline reflects the minimum frequency, intensity, and duration of upper-body aerobic exercise that has been shown to significantly improve the cardiometabolic health outcomes. The new guideline, states that for cardiometabolic health benefits, adults with a spinal cord injury are suggested to engage in at least;

30 Min of moderate to vigorous intensity aerobic exercise, 3 times per week

Possible barriers and facilitators to guidelines[edit | edit source]

The panel developing the guidelines have also identified barriers and facilitators unique to these guidelines:

- specifying different guidelines for improving fitness and cardiometabolic health might create confusion (i.e., people may not be sure which guideline to follow), as might having guidelines that differ from what is promoted for the general population;

- use of the term ‘exercise’, as opposed to ‘physical activity’, in the guideline may constrain thinking about types of activities that people with a spinal cord injury can participate in;

- importance of improving one’s fitness might be overshadowed by launching a new cardiometabolic health guideline.

Role of Physiotherapy in Promoting Guidelines[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapists have always had a close relationship with exercise, the profession was founded on the work of remedial gymnasts and the profession has a rich history of prescribing rehabilitative exercise. The global physical inactivity crisis and the epidemic of lifestyle-related, non-communicable diseases have created an urgent need to build on our rich history of prescribing exercise and develop our approaches for prescribing physical activity. Creating a more active population requires joined-up thinking and action from many stakeholders; physiotherapists need to be active in engaging with individuals and communities.

"Physiotherapists are ideally placed to help the dissemination of these Physical Activity Guidelines for Spinal Cord Injury because they interact on a daily basis with patients at the start of their journey after their Spinal Cord Injury." Dot Tussler, Physiotherapist at Stoke Mandeville Hospital

Resources[edit | edit source]

National Centre for Sport & Exercise Medicine

SCI Action Canada

Peter Harrison Centre for Disability Sport

- Fit For Life; A Guide for Adults with Spinal Cord Impairment

- Fit for Sport; A Guide for Adults with a Spinal Cord Impairment

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ World Health Organization. Global recommendations on physical activity for health. World Health Organization; 2010.

- ↑ National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine. Prof Vicky Tolfrey | Why We Need SCI-Specific Evidence. Available from: https://youtu.be/nqcbIn1XyWo[last accessed 20/02/19]

- ↑ National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine. Jan van der Scheer | How SCI Exercise Guidelines were Developed. Available from: https://youtu.be/Jd5xaBVaLv0[last accessed 20/02/19]

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Martin Ginis KA, Hicks AL, Latimer AE, Warburton DE, Bourne C, Ditor DS, et al. The development of evidence-informed physical activity guidelines for adults with spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:1088–96.

- ↑ National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine. Jan van der Scheer | How the Guidelines will be Translated. Available from: https://youtu.be/oEOs_0Xor-4[last accessed 20/02/19]

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Ginis KA, van der Scheer JW, Latimer-Cheung AE, Barrow A, Bourne C, Carruthers P, Bernardi M, Ditor DS, Gaudet S, de Groot S, Hayes KC. Evidence-based Scientific Exercise Guidelines for Adults with Spinal Cord Injury: An Update and a New Guideline. Spinal Cord. 2018 Apr;56(4):308.

- ↑ Vincent GE, Jay SM, Sargent C, Vandelanotte C, Ridgers ND, Ferguson SA. Improving Cardiometabolic Health with Diet, Physical Activity, and Breaking Up Sitting: What about Sleep?. Frontiers in Physiology. 2017 Nov 8;8:865.

- ↑ SCIActionCanada. Physical Activity Guidelines for Adults with SCI - 2. 2011 Available from: https://youtu.be/F97y4XQSECc

- ↑ National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine. Dot Tussler | The Importance of SCI Exercise Guidelines for Physios. Available from: https://youtu.be/Giqt6jT27nU[last accessed 20/02/19]

- ↑ National Centre for Sport and Exercise Medicine. Dot Tussler | Role of Physios in helping People with SCI be Active. Available from: https://youtu.be/w6P3hQSUr-Y[last accessed 20/02/19]