Congestive Heart Failure - Pharmacotherapy

Introduction[edit | edit source]

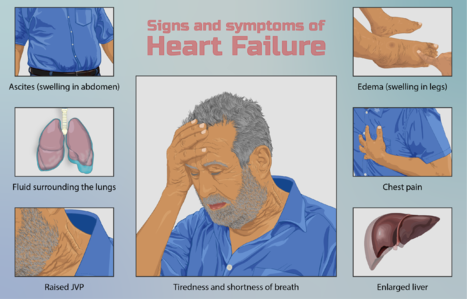

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) refers to the clinical syndrome caused by inherited or acquired abnormalities of heart structure and function, causing a constellation of symptoms and signs that lead to decreased quality and quantity of life.[1]See link for a comprehensive description.

Treatment involves a multidisciplinary team and incorporates lifestyle, allied health, pharmacological, and even surgical therapies, often specific to the underlying etiology. It incorporates pharmacotherapy, along side, treatment of comorbidities and complications (e.g. obesity, hypertension, depression) and lifestyle interventions (education, cessation of smoking and alcohol consumption, exercise therapy and improved diet). This article focuses on drug therapy.

Pharmacological Management of Heart Failure[edit | edit source]

Beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, glycosides, and diuretics are the key medications used for managing congestive heart failure through regulating renal function and the sympathetic nervous system. Adverse effects of these drugs are covered in the below links, providing implications of each drug in regards to physical therapy activity.

Drugs used in heart failure include those used to initially manage mild to moderate failure and those used more commonly in severe to very severe conditions.

First Agents Used:

- ACE Inhibitors in the treatment of congestive heart failure. Angiotensin Converting Enzyme (ACE) Inhibitors work by increasing vasodilation and decreasing workload of the heart in patients with CHF.

- Diuretics Drugs that promote the removal from the body of excess water, salts, poisons, and accumulated metabolic products, such as urea. See also Aldosterone Receptor Antagonist Diuretics in the treatment of congestive heart failure.

- Glycosides and Congestive Heart Failure Cardiac glycosides are a class of drugs that includes digoxin, digitoxin and ouabain. Such agents increase the force of contraction of the heart ie a positive inotropic action) which underlies their use in some cases of heart failure[2].

- Beta-Blockers (mild-to-moderate disease). These drugs provide their beneficial effect by decreasing the excessive activity of the sympathetic nervous system which is characteristic of CHF.

Additional Agents:

- More aggressive diuretic therapy eg Loop diuretics such as Furosemide (Lasix), one of the most commonly used drugs in the treatment edema caused by congestive heart failure (CHF).

- Vasodilators

- Parenteral inotropic agents (dobutamine). There are very few options for patients in the end stages of CHF. Home inotropic infusions offer a nonsurgical option to improve both patients' symptoms and quality of life. The use of these medications requires advanced planning as well as symptom management and device management. They can be safely used throughout the continuum of care as pediatric/adult “bridges to transplant” through hospice care.[3]

Selection of agents and their combinations depend on initial clinical state and on patient responsiveness to initial therapy[4].

Conclusion[edit | edit source]

As part of an interdisciplinary team, it is also essential that physical therapists be knowledgeable regarding the pharmacological treatment of CHF. The drugs used to manage CHF work by increasing cardiac contractility or decreasing cardiac workload. These pharmacological effects may potentially allow for drug therapy and exercise therapy to have the mutually reinforcing benefits of increasing exercise tolerance and strengthening cardiac function. Despite these potential benefits, the drugs used to treat CHF may also cause serious side effects including dizziness, nausea, arrhythmias, fatigue, and weakness. Knowledge of these side effects will allow the therapist to consider the response to exercise prescription and other modalities in the context of the patient’s pharmacotherapy. Early recognition of these symptoms may prevent development of serious complications or even death.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Radiopedia CHF Available: https://radiopaedia.org/articles/congestive-cardiac-failure?lang=us(accessed 2.6.2021)

- ↑ Pharmacology education Glycosides Available:http://www.pharmacologyeducation.org/positive-inotropic-drugs-cardiac-glycosides-digoxin (accessed 3.6.2021)

- ↑ Lyons MG, Carey L. Parenteral inotropic therapy in the home: an update for home care and hospice. Home Healthcare Now. 2013 Apr 1;31(4):190-204.Available: https://journals.lww.com/homehealthcarenurseonline/Fulltext/2013/04000/Parenteral_Inotropic_Therapy_in_the_Home__An.4.aspx(accessed 3.6.2021)

- ↑ Pharmacology 2020 Chapter 10: Pharmacological Management of Congestive Heart Failure Available:https://www.pharmacology2000.com/Cardio/CHF/chfobj1.htm (accessed 3.6.2021)