Perceptual-Motor Abilities of Infants in the 1 to 2 Month Period

Top Contributors - Robin Tacchetti, Tarina van der Stockt, Jess Bell, Kim Jackson, Ewa Jaraczewska and Jorge Rodríguez Palomino

Introduction[edit | edit source]

During the 1 to 2 month old period infants gain various new skills using their perceptual-motor abilities. Perception involves understanding, categorising and translating sensory information. Examples of perceptual ability include:

- Recognising:

- Familiar faces vs. non-familiar faces

- The voice of a family member

- Distinguishing:

- The height of an object

- The colour of an object

- The depth of an object

Motor ability refers to an infant's capacity to control their body movements. Motor abilities encompass all movements of the body including, waving, kicking, reaching, grasping, etc. Perceptual and motor abilities are collaborative as infants use their perceptual skills to decide on the correct motor action to undertake.[1]

Initially, an infant's perceptual-motor behaviour is spontaneous. During the 1 to 2 month period, infants transition from spontaneous movement to intentional movements. During this period of development, you can expect to see the following:[2]

- Movements shift from writhing to fidgety

- Greater head control and movements allowing increased ability to visually reach and gather information

- Turning towards sounds and visual events within their environment

- Exploring their bodies, clothing and surrounding surfaces with their hands and feet

- Successful and intentional reaching

Communication and Social Interaction[edit | edit source]

Newborns in the 1-2 month period will begin to demonstrate more complex, sustained and expressive social behaviours. Some of the types of communication and social development you might notice in an infant in the 1 to 2 month period are listed below:[2]

- First smiles

- Turns head towards voices and other sounds within the environment

- Quietens their limbs movements

- Smiles in response to sounds

- Interest in faces

- Recognises familiar faces

- Makes eye contact

- Has different cries for different needs

- Produces pre-speech sounds known as protophones, which includes grunts, coos, and gurgles

Infant Vocalisation[edit | edit source]

To practise and explore sounds, infants will spontaneously vocalise, producing a range of sounds. Infants can alter these sounds by changing their emotional tone or inflexion. These different sounds will provide the foundation for later babbling and words. Pre-speech sounds such as grunts, squeals and coos are referred to as protophones.[2]

Caregiver Interaction[edit | edit source]

Interactions between the caregiver and infant require clear cues from both the infant and the caregiver to facilitate responses to each other. Taking cues from one another allows the infant and caregiver to change or adapt their behaviour in response to the interaction. This mutual interactive environment teaches the infant communication and social interaction.[3] Caregivers speak to infants in a language called motherese or baby talk. This type of infant directed speech allows adults to alter their acoustic properties to use a higher pitch, increased pitch range and variability, and a slower speech rate. Research shows that these vocal adjustments happen across all populations.[2]

"Various aspects of motherese also known as infant-directed speech (IDS) have been studied for many years. As it is a widespread phenomenon, it is suspected to play some important roles in infant development. Therefore, our purpose was to provide an update of the evidence accumulated by reviewing all of the empirical or experimental studies that have been published since 1966 on IDS driving factors and impacts. Two databases were screened and 144 relevant studies were retained. General linguistic and prosodic characteristics of IDS were found in a variety of languages, and IDS was not restricted to mothers. IDS varied with factors associated with the caregiver (e.g., cultural, psychological and physiological) and the infant (e.g., reactivity and interactive feedback). IDS promoted infants' affect, attention and language learning. Cognitive aspects of IDS have been widely studied whereas affective ones still need to be developed. However, during interactions, the following two observations were notable: (1) IDS prosody reflects emotional charges and meets infants' preferences, and (2) mother-infant contingency and synchrony are crucial for IDS production and prolongation. Thus, IDS is part of an interactive loop that may play an important role in infants' cognitive and social development." [4]

Mirroring[edit | edit source]

Caregivers will often "mirror" or imitate newborns' facial expressions, jaw and lip movements and vocalisations. This allows the infant to hear and see copies of their own activity.[2] These parental responses are both instinctive and functionally important as they help the infant increase their social communication skills.[5]

** Infants begin to recognise familiar faces and smile at them during the 1 to 2 month period.

Watch this video by Reach Out and Read to see how caregivers and infants communicate:

General Movements[edit | edit source]

Within the 1 to 2 month period, infants transition from generalised writhing movements to fidgety movements with an increase in fidgety movements towards the end of this period.[6] Writhing movements are characterised by complex, whole body movements including the arm, leg, trunk and neck in variable arrangements.[7] These movements vary in range of motion, speed and intensity and have a gradual onset and end. Writhing movements wax and wane and give the appearance of being fluid and graceful. At around 9 weeks, fidgety movements replace writhing. Fidgety movements usually continue until around 16 to 20 weeks old.[2] Fidgety movements are characterised by small movements of moderate speed with variable acceleration of the legs, neck and trunk in all directions.[8][7]The presence and character of fidgety movements are good indicators of the integrity of the infant's nervous system.[6]

Supine[edit | edit source]

Young infants generally hold their head rotated to one side when lying supine. When the head moves into rotation, the asymmetrical tonic neck reflex (ATNR) might occur (see figure). However, this reflex is not obligatory. By the end of the 1 to 2 month period, infants are more likely to hold their head in the midline when lying supine and can easily turn to either side to explore their environment. Infants can then track an object from the side to the midline, but not across the midline. They can also track an object in the downwards direction.[2]

Prone[edit | edit source]

Infants in the 1 to 2 month period can briefly lift their heads up when in a prone position. Their feet remain in dorsiflexion, increasing as they flex their hips and knees, and decreasing as they extend their lower extremities. Kicking can be observed in a prone position. Infants may kick one or both legs. Unilateral kicking is associated with a lateral weight shift in weight-bearing and a lateral flexion of the trunk.[2]

Rolling[edit | edit source]

Many infants do not like being placed in prone and quickly get upset and roll from prone to supine. As described below, rolling is initiated in one of two ways (the following describe an infant rolling onto their left side). The infant:

- Lifts their head

- Extends their thoracic spine

- Extends the hips and knees

- Shifts their centre of mass caudally

- Retracts their right shoulder

- Flexes their right hip

- Falls onto their back[2]

OR

- Lifts their head

- Pushes down with their right hand

- Extends their elbow

- Extends their thoracic spine

- Shifts their centre of mass caudally

- Falls onto back[2]

In the second movement sequence, there is no associated hip extension; the hips remain flexed throughout.[2]

Weight-bearing through the hands in prone is seen at the end of the 1 to 2 month period. Extension of the hips is seen with thoracic and head extension. Knee movement does not always couple with hip movement, which allows disassociation and freedom for each joint.[2]

Reaching and Grasping[edit | edit source]

Infants in the 1 to 2 month period will reach for a toy by making large swiping motions with their elbow and fingers extended. Predominately, their hands do not make contact with the object. As they move through this period, extension of the fingers becomes less pronounced and small shoulder and elbow movements help facilitate grasping the toy. At around 10-12 weeks old, the infant's ability to steady their head and trunk while moving their upper extremities becomes more consistent. This allows them to reach for fixed or suspended toys. Reaching at this point becomes more goal directed.[2] [9] Flexion and extension of the fingers are often seen as infants interact with various surfaces they encounter.[10][2] Exploring toys with their hands and fingers permits them to learn about the behaviour, structure and texture of an object.[2]

Kicking[edit | edit source]

Infants in the 1 to 2 month period have a physiological flexor stiffness at the knees and hips. By 10 weeks, the infant will gain full lower extremity range of motion and is able to extend the hip and knee with an associated anterior pelvic tilt. Single or alternating leg kicking can be seen during this time with hip and knee motions coupled. The feet will occasionally push down on a surface, causing lateral trunk weight shift with trunk and head extension. The feet will demonstrate increased plantarflexion during this time as well.[2]

Pull to Sit[edit | edit source]

Infants can pull to sit keeping their head in line with their trunk when they are 1-2 months old. As they anticipate being pulled up, they can activate their trunk and neck flexor muscles while stiffening their hips and upper extremities. Once upright, these infants are able to move their head to gaze at the person lifting them.[2]

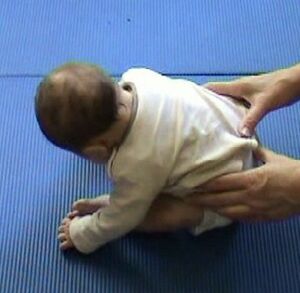

Sitting[edit | edit source]

Infants in the 1 to 2 month period will need support in sitting. Trunk support in sitting has the following characteristics:[2]

- Head falls forward

- Brief period of scapular retraction

- Increased flexion of the elbows

- Forearm pronation

- Extension of the wrist

- Flexion of the fingers

- Feet flexed and everted

At around 6 weeks, infants can extend their thoracic spine and head when supported around their waist. When they are closer to 2 months, infants can maintain a semi-erect position with support at their hips. This facilitates their neck and trunk extensors.[2]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Understanding Newborn Behaviour

- Newborn Perceptual Motor Behaviour

- Development Skills Training for the 1-2 month old

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ California Department of Education. Perceptual and Motor Development Domain. Last reviewed 2021. Accessible at:https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/itf09percmotdev.asp#percdev

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 Versfeld P. Perceptual-Motor Abilities in the Infant 1-2 Month Period Course. Physioplus. 2022.

- ↑ Chung FF, Wan GH, Kuo SC, Lin KC, Liu HE. Mother–infant interaction quality and sense of parenting competence at six months postpartum for first-time mothers in Taiwan: a multiple time series design. BMC pregnancy and childbirth. 2018 Dec;18(1):1-3.

- ↑ Saint-Georges, C., Chetouani, M., Cassel, R., Apicella, F., Mahdhaoui, A., Muratori, F., Laznik, M. C., & Cohen, D. (2013). Motherese in interaction: at the cross-road of emotion and cognition? (A systematic review). PloS one, 8(10), e78103.

- ↑ Murray L, Bozicevic L, Ferrari PF, Vaillancourt K, Dalton L, Goodacre T, Chakrabarti B, Bicknell S, Cooper P, Stein A, De Pascalis L. The effects of maternal mirroring on the development of infant social expressiveness: The case of infant cleft lip. Neural plasticity. 2018 Dec 17;2018.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Einspieler, C., Peharz, R., & Marschik, P. B. (2016). Fidgety movements - tiny in appearance, but huge in impact. Jornal de pediatria, 92(3 Suppl 1), S64–S70.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Doroniewicz I, Ledwoń DJ, Affanasowicz A, Kieszczyńska K, Latos D, Matyja M, Mitas AW, Myśliwiec A. Writhing movement detection in newborns on the second and third day of life using pose-based feature machine learning classification. Sensors. 2020 Jan;20(21):5986.

- ↑ Hadders‐Algra M. Neural substrate and clinical significance of general movements: an update. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology. 2018 Jan;60(1):39-46.

- ↑ Corbetta D, Wiener RF, Thurman SL. Learning to reach in infancy. Reach-to-Grasp Behavior. 2018 Aug 28:18-41.

- ↑ DiMercurio A, Connell JP, Clark M, Corbetta D. A naturalistic observation of spontaneous touches to the body and environment in the first 2 months of life. Frontiers in psychology. 2018:2613.