Parkinson's Lifestyle Medicine - Nutrition and Sleep Hygiene

Original Editor - Thomas Longbottom based on the course by Z Altug

Top Contributors - Thomas Longbottom, Kim Jackson, Tarina van der Stockt, Lucinda hampton and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Approximately 10 million people around the world are currently living with Parkinson’s.[1] Meta-analysis of worldwide data reveals that the prevalence of Parkinson’s increases with age, quadrupling from a level of almost 0.5% in the seventh decade of life to approximately 2% for those over the age of 80.[2] Other sources report that Parkinson's affects 1.5-2% of the population over the age of 60.[3] Parkinson’s is associated with the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra of the midbrain, and it is typified clinically by resting tremor, rigidity, and bradykinesia along with a number of non-motor features such as anosmia, sleep behaviour disorder, depression, autonomic dysfunction, and cognitive dysfunction.[4] The aetiology of this disease is not fully understood, but there is some combination of environmental and genetic factors presumed to be causative.[4] Among these are various lifestyle factors such as tobacco use, dietary intake, and physical activity.[5][6]

Lifestyle Medicine[edit | edit source]

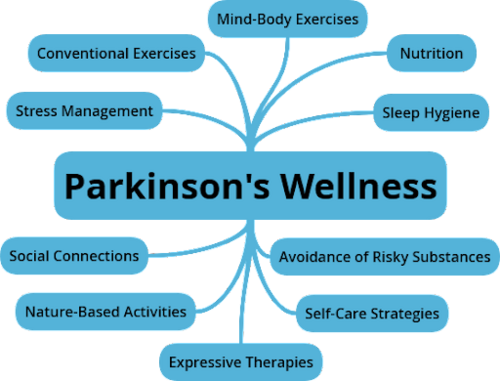

According to the Lifestyle Medicine Handbook, Lifestyle Medicine involves the use of evidence-based lifestyle therapeutic approaches to treat, reverse, and prevent lifestyle-related chronic disease.[8] These include:

- A predominantly whole food, plant-based diet

- Regular physical activity

- Adequate sleep

- Stress management

- Social connections

- Avoidance of risky substance abuse[8]

The aim of Lifestyle Medicine is to treat the underlying causes of disease rather than just addressing the symptoms. This involves helping patients learn and adopt healthy behaviours. Lifestyle interventions have the potential to impact the prognosis of many chronic diseases, leading not only to better quality of life for many, but also potentially reducing their costs to the healthcare system.[9] While a tendency to think of Lifestyle Medicine as being the domain of the physician is understandable, other providers such as dietitians, social workers, behavioural therapists and lifestyle coaches are also integral.[9] It is also well within the scope of the physiotherapist:[10]

- Diet and nutrition are key elements in many of the conditions managed by physiotherapists

- Physiotherapists are experts in exercise and movement

- Prevention, health promotion, fitness and wellness are crucial aspects of physiotherapy care[10]

The focus of this page will be on discussing resources and concepts related to the nutrition and sleep hygiene aspects that have the potential to impact individuals with Parkinson's.

Nutrition[edit | edit source]

Nutrition involves the intake of food for the sustenance of the body's tissues and functions. It provides energy, supports growth, healing, recovery and maintenance, and helps maintain a healthy immune system. Food also has a role in providing for social interaction.[7] Diet and nutrition can be an important therapeutic component used to help manage various medical conditions such as cystic fibrosis, coeliac disease, diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular disease and others.[11] Food-drug interactions have the potential to interfere with the effectiveness of certain medications, and this can be significant for individuals with Parkinson's.[12] Certain foods can also impact disease processes. For example, limiting dietary protein may help reduce dyskinesia for some individuals.[13]

There is evidence that the Mediterranean Diet, generally high in fruits and vegetables, nuts and legumes, whole grains, seafood, and unsaturated fats such as olive oil, and low in meat protein and dairy, may help reduce the risk for Parkinson's and delay its onset.[14][15] The Mediterranean Diet also can increase cognitive function in individuals with Parkinson's, improving executive function, language, attention, concentration, and memory.[16]

Practical strategies for good nutrition:

- Choose foods wisely, choosing a variety of colourful and predominantly plant-based foods.

- Learn to cook wholesome foods using simple recipes.

- Try mindful eating strategies. These include eating with friends and family, and eating more slowly by looking at the shape of the food, feeling the texture, savouring the aromas and tasting the flavours.

- Consider a consultation with a registered dietitian and perhaps a culinary medicine specialist to optimise diet and nutrients for overall health and well-being.[7]

Sleep Hygiene[edit | edit source]

Adequate sleep is important for general health and wellbeing. Adults typically need 7 or more hours of sleep every night.[17]

Benefits of quality sleep:

- Improves productivity and alertness[18]

- Aids healing and recovery[18]

- Enhances motor learning[19]

How to know if a person is getting enough sleep:

- Do they wake up feeling refreshed?

- Are multiple attempts needed to get up after the alarm clock goes off?

- Is lots of coffee needed in the morning?

- Are they yawning and feeling fatigued throughout the day?

- Are they routinely having difficulty concentrating on work and personal tasks?[7]

The clinician has a number of sleep screening tools available to determine if a person with Parkinson's has sleep dysfunction, including the Parkinson's Disease Sleep Scale, the Scales for Outcomes in Parkinson's Disease -- Sleep, the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, and the Epworth Sleepiness Scale. Refer to these resources linked below for more details.

There are a number of strategies to improve sleep quality and to offset the negative effects of poor sleep quality. These might include the application of light therapy during the day, or engagement in high intensity exercise.[20][21]

The following 20 patient education strategies[7] may help improve restorative sleep:

- Establish regular bedtime habits such as brushing teeth, washing the face, and setting the alarm clock.

- Create a comfortable room that is dark, quiet, and cool, with a temperature ideally between 17°C and 28°C (62°F and 82°C) and a humidity level between 40-60%.[22] Other studies may give different guidelines, take into consideration various geographic locations and adaptions to temperature when discussing this with clients.

- Sleep in a comfortable bed.

- Use a comfortable pillow.

- Turn the clock away from the bed to prevent "clock-watching" and to avoid the light from the clock during the night.

- Engage in relaxing activities before sleep, such as reading or watching a funny television show.

- Stay off of the smartphone or computer near bedtime.

- Avoid caffeine from foods and beverages for at least 3-5 hours before bedtime.

- Consider airing out the bedroom with fresh air prior to sleeping.

- Avoid late night eating and heavy meals within 3 hours of bedtime.

- Avoid excessive fluid intake near bedtime to prevent frequent bathroom trips during the night.

- Stop smoking. The nicotine in tobacco is a stimulant.

- Avoid alcohol near bedtime as it may fragment sleep.

- Try a foot bath or a hot bath 1-2 hours prior to bedtime.

- Use lavender essential oil through a soap or lotion before bedtime.

- Exercise during the day with conventional exercises such as walking, cycling, or weight training, but avoid intense exercise near bedtime.

- Practise mind body exercises such as qigong or yoga.

- Consider trying a weighted blanket at night. These can be anxiety-reducing and comforting.

- Speak with your physician about magnesium supplementation.

- Learn strategies to manage stress.

If the clinician finds that the above patient education strategies and sleep optimisation guidelines are not adequately effective, a referral to a sleep specialist, psychologist or counsellor for training in cognitive behavioural therapy for chronic insomnia may be appropriate.[7]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Nutrition:

- Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: https://www.eatright.org/

- Forks Over Knives: https://www.forksoverknives.com/

- Healthy Kitchens, Healthy Lives: https://www.healthykitchens.org/

- Nutrition Facts: https://nutritionfacts.org/

- Office of Dietary Supplements: https://ods.od.nih.gov/

- Teaching Kitchen Collaborative: https://teachingkitchens.org/

- Sleep Hygiene:

- Screening Tools for Sleep Dysfunction

- Video (11 mins): Autogenic Training for Relaxation

- File:Script for Autogenic Relaxation.pdf

- App: Breethe (https://breethe.com/)

- App: Calm (https://www.calm.com/)

- App: Headspace (https://www.headspace.com/)

- App: Relax Melodies (https://www.relaxmelodies.com/)

- Product: Weighted Blanket (https://bearaby.com)

- Product: Weighted Blanket (https://protac.dk/uk/index)

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine: https://aasm.org/ and https://sleepeducation.org/

- American Sleep Association: https://www.sleepassociation.org/

- Better Sleep Council: https://bettersleep.org/

- National Sleep Foundation: https://www.sleepfoundation.org/

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Statistics [Internet]. Parkinson's Foundation. [cited 2021Dec28]. Available from: https://www.parkinson.org/Understanding-Parkinsons/Statistics

- ↑ Pringsheim T, Jette N, Frolkis A, Steeves TDL. The prevalence of Parkinson's disease: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Movement Disorders 2014;29(13):1583–90.

- ↑ Venes D, Taber CW. Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis; 2021.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Simon DK, Tanner CM, Brundin P. Parkinson Disease Epidemiology, Pathology, Genetics, and Pathophysiology. Clinics in Geriatric Medicine 2020;36(1):1–2.

- ↑ Ritz B, Ascherio A, Checkoway H, Marder KS, Nelson LM, Rocca WA, et al.. Pooled Analysis of Tobacco Use and Risk of Parkinson Disease. Archives of Neurology [Internet] 2007;64(7):990.

- ↑ Paul KC, Chuang Y, Shih I, Keener A, Bordelon Y, Bronstein JM, et al.. The association between lifestyle factors and Parkinson's disease progression and mortality. Movement Disorders 2019;34(1):58–66.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 Z Altug. Parkinson's Lifestyle Medicine - Nutrition and Sleep Hygiene. Plus Course. 2021.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Frates B, Bonnet JP, Joseph R, Peterson JA. Lifestyle Medicine Handbook: An introduction to the power of Healthy Habits. Monterey, CA: Healthy Learning; 2021.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 1. Bodai B. Lifestyle Medicine: A Brief Review of Its Dramatic Impact on Health and Survival. The Permanente Journal 2017;22(1).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Worman R. Lifestyle medicine: The role of the physical therapist. The Permanente Journal. 2020;24:18.192.

- ↑ Health [Internet]. EatRight. [cited 2021Dec28]. Available from: https://www.eatright.org/health

- ↑ Escott-Stump S. Nutrition and diagnosis-related care 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer Health; 2015.

- ↑ Raymond JL, Morrow K. Krause and Mahan's Food & the Nutrition Care Process. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2021.

- ↑ Metcalfe‐Roach A, Yu AC, Golz E, Cirstea M, Sundvick K, Kliger D, et al. MIND and Mediterranean diets associated with later onset of parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2021;36(4):977–84.

- ↑ Yin W, Löf M, Pedersen NL, Sandin S, Fang F. Mediterranean dietary pattern at middle age and risk of parkinson's disease: A Swedish cohort study. Movement Disorders. 2020;36(1):255–60.

- ↑ Paknahad Z, Sheklabadi E, Derakhshan Y, Bagherniya M, Chitsaz A. The effect of the Mediterranean diet on cognitive function in patients with parkinson’s disease: A randomized clinical controlled trial. Complementary Therapies in Medicine. 2020;50:102366.

- ↑ Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, Buysse D, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine. 2015;11(06):591–2.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Kryger MH, Roth T, Dement WC. Principles and practice of Sleep Medicine. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- ↑ Al-Sharman A, Siengsukon CF. Sleep enhances learning of a functional motor task in young adults. Physical Therapy. 2013;93(12):1625–35.

- ↑ Videnovic A, Klerman EB, Wang W, Marconi A, Kuhta T, Zee PC. Timed light therapy for sleep and daytime sleepiness associated with parkinson disease. JAMA Neurology. 2017;74(4):411.

- ↑ Amara AW, Wood KH, Joop A, Memon RA, Pilkington J, Tuggle SC, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of exercise on objective and subjective sleep in parkinson's disease. Movement Disorders. 2020;35(6):947–58.

- ↑ Desjardins S, Lapierre S, Vasiliadis HM, Hudon C. Evaluation of the Effects of an Intervention Intended to Optimize the Sleep Environment Among the Elderly: An Exploratory Study. Clin Interv Aging. 2020;15:2117-2127. 2020.