Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures

Top Contributors - Mathieu Vanderroost, Angeliki Chorti, Lucinda hampton, Jasper Vermeersch, Jon Room, Kim Jackson, Jelle Van Hemelryck, Khloud Shreif, Laura Ritchie, Vidya Acharya, Lauren Lopez, 127.0.0.1, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Kai A. Sigel, WikiSysop and Claire Knott

Definition / Description[edit | edit source]

Osteoporotic (fragility) fractures are fractures that result from mechanical forces that would not ordinarily result in a fracture according to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) clinical guidelines[1].

Vertebral compression fractures (VCFs) of the spinal column:

- Occur secondary to an axial/compressive (and to a lesser extent, flexion) load with a resultant biomechanical failure of the bone resulting in a fracture.

- Compromise the anterior column of the spine, thereby resulting in compromise to the anterior half of the vertebral body (VB) and the anterior longitudinal ligament (ALL).

- Do not involve the posterior half of the VB and do not involve the posterior osseous ligamentous complex. The former distinguishes a compression fracture from a burst fracture.

- Usually considered stable and do not require surgical instrumentation.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

- The most common etiology of VCFs is osteoporosis, making these fractures the most common fragility fracture.

- Compression fractures demonstrate a bimodal distribution with younger patients sustaining these injuries secondary to high energy mechanisms (fall from a height, MVA, etc.).

- Compression fractures by definition only involve compromise to the anterior column alone.

- VCFs are considered "stable" fracture patterns.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Population studies have shown that the annual incidence of VCFs is 10.7 per 1000 women and 5.7 per 1000 men.

- VCFs are the most common fragility fracture reported in the literature.

- Approximately 1 to 1.5million VCFs occur annually in the united states (US) alone.

- Estimated that 40% to 50% of patients over age 80 years have sustained a VCF either acutely, or recognized incidentally during clinical workup for a separate condition.

- Thoracolumbar junction (i.e., the segment from T12 to L2) location most often affected (60% to 75% of VCFs), and another 30% occur at the L2 to L5 region

In the elderly patients

- 30% of VCFs occurring while the patient is in bed

- As the population continues to age, the population at risk of sustaining low energy fragility fractures will continue to increase as well.

- Largely unreported and are probably more common radiographically (present up to 14% of women older than 60 years in one study)[4]

- Currently, 10 million Americans are already diagnosed with osteoporosis, and another 34 million have osteopenia.

The below short video gives a brief overview of compression fractures

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Vertebral fractures present with pain and loss of mobility.[4]

Symptoms of vertebral fracture can include

- Back pain is common in elderly patients. Decrease when lying on the back. [6][7].

- Three quarters of patients with vertebral fractures do not seek medical attention and up to 70% of vertebral fractures may not result in notably severe symptoms [8].

Loss of height and acute pain. Height loss of the osteoporotic fractured vertebra may be mild (20-25%), moderate (25-40%) or severe (> 40%). It commonly affects the thoracolumbar region, though any vertebra may be disturbed. - The pain of acute fracture usually lasts 4 to 6 weeks with intense pain at the site of fracture.

- The pain resolves over a period of six to 12 weeks.

- Chronic pain may also occur in patients with multiple compression fractures, height loss and low bone density (also due to structural changes or osteoarthritis).

- Radiographic VCF may not be symptomatic. The greater the deformity, the greater the likelihood of pain and disability.

- As height is lost, patients experience discomfort from the rib cage pressing downward on the pelvis.

- Patients develop an exaggerated thoracic kyphosis and/or an exaggerated lumbar lordosis[8]which may result in decreased exercise tolerance and reduced abdominal space giving rise to early satiety and weight loss.

- Sleep disorders may occur and decreased self esteem +/- depression.

- Self care may become difficult. [9][10][11].

- Associated with an increased morbidity and increased mortality[8][12]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Diagnosed on Xrays when there is a loss of height in the anterior, middle, or posterior dimension of the vertebral body that exceeds 20%.

Osteoporotic spine fractures can be graded based on vertebral height loss as:

- Mild: up to 20-25%

- Moderate: 25-40%

- Severe: >40%

Chronicity of the fracture indicates its temporal relationship with symptoms and hence is an important determination.

On conventional imaging, acute fracture signs include cortical breaking or impaction of trabeculae; in the absence of these signs fractures are chronic.

In uncertain cases, MRI signs of oedema (acute) and presence of radiotracer uptake on bone scintigraphy (acute) help decide the age of the fracture.

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Visual analogue scale for overall pain (VAS).

- Quality of Life questionnaire: this can be measured with the use of the Quality of Life Questionnaire of the European Foundation for Osteoporosis (QUALEFFO). An other possibility is to use the Assessment of Quality of Life (AQoL) questionnaire or the European Quality of Life–5 Dimensions (EQ–5D) scale.

- Physical functioning: measured by a modified 23-item version of the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire.

- Pain at night and at rest (VAS score)[13]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Clinical assessment of vertebral fractures is generally poor and reliance is made on imaging studies for diagnosis[10].

2 tests that help the practitioner to predict more accurately which patients have an acute vertebral fracture[14].

- Closed-fist percussion sign[14]

This test has a sensitivity of 87,5% and a specificity of 90%, which is good. Stand behind the patiënt and the patiënt stand in front of a mirror allowing you to see the reaction of the patiënt. Firm closed-fist percussion is used to examine the entire length of the spine. The clinical sign is positive when the patiënt complains of a sharp, sudden pain. - The supine sign[14] This test has a sensitivity of 81,25% and a specificity of 93,33%, which is also pretty good. The patiënt is asked to lie supine with only one pillow for the head. The clinical sign is positive when the patiënt is unable to lie supine due to severe pain.

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Conservative management of acute osteoporotic compression fractures - goals: reducing pain and improving functional status includes

- Acetaminophen, ibuprofen, opioids,

- Physiotherapy

- Rehabilitation programs

- Bed rest.

- Bracing for compression fractures is often done for patient comfort and is unlikely to influence spinal stability. A small study did support the use of semirigid thoracolumbar orthosis for gait improvement.

- Treatment of the underlying disease (osteoporosis) is the recommended approach.

For persistent pain and the failure of conservative treatments, surgical intervention is necessary.

- Vertebroplasty is usually an outpatient procedure that takes one to two hours where under guided imaging, a needle get inserted into the vertebral body and cement is injected. This cement hardens quickly and stabilizes the fracture.

- Kyphoplasty is a very similar procedure, but in this case, a balloon is used to expand the vertebral body before njecting the cement. [15]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

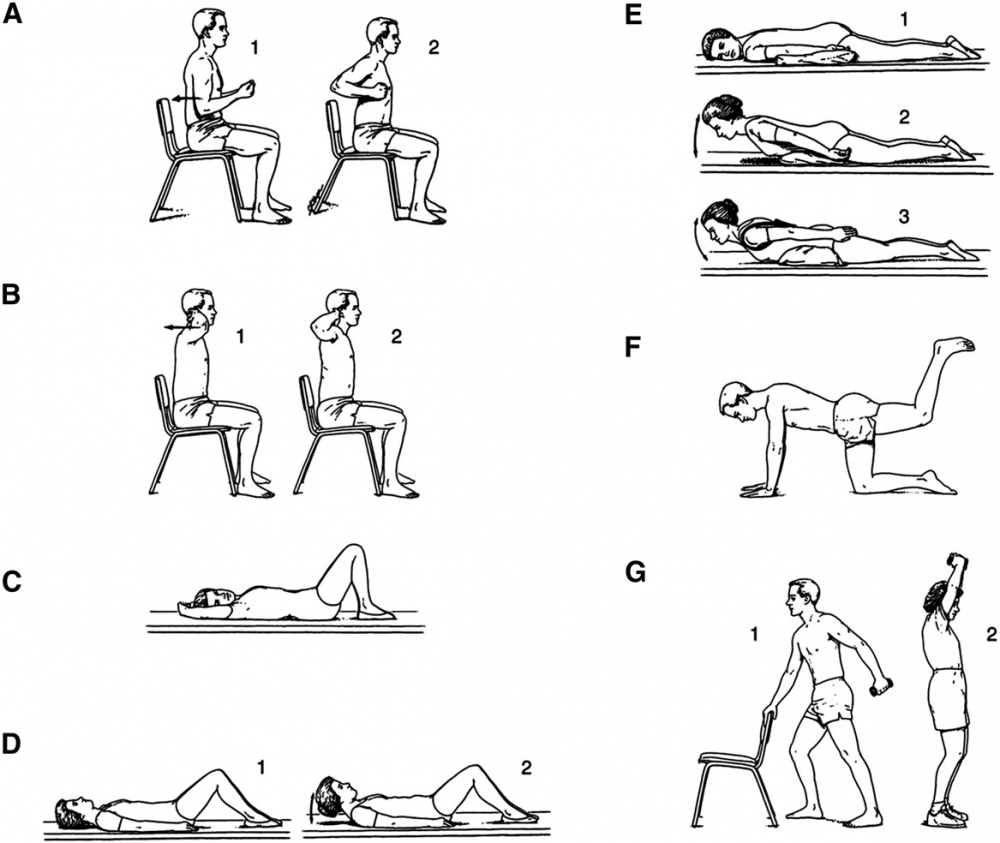

After a short period of bed rest patients should begin mobilisation with a rehabilitation and exercise program. The goals of rehabilitation are the prevention of falls, reduction of the Thoracic Hyperkyphosis, enhancing axial muscle strength and providing correct spine alignment[16].

Treatment approaches include:

- Strengthening exercise, stabilisation exercise, balance training, stretching, relaxation techniques, manual therapy and taping[17][18].

- Exercises such as walking help to maintain or improve bone density in an osteoporotic population.

- Strengthening exercises, using weights or resistance bands help maintain or improve bone density at the location of the targeted muscle attachments[19]. Maintaining bone health is extremely important, especially in the elderly as there typically is a decline in bone mass with age.

- Strengthening and flexability exercises improve overall physical function and postural control (important to reduce risk for falls).[20].

- Combined balance and progressive strength training programme produced the best results in terms of maintaining leg strength, balance, bone mineral density and physical function compared to balance or strength training alone[21][22][23].

- Spinal extensor strengthening programme and a dynamic proprioceptive programme increase bone density and reduced the risk of VCFs.[24].

- Back extensor exercises improve muscle strength, providing a better dynamic-static posture and reduction of the kyphotic deformity. Correction of the kyphosis also results in pain relief, increased mobility and an improvement in the quality of life[25].

Postural taping can help in maintaining postural alignment. Tape is applied to the skin to provide increased proprioceptive feedback about postural alignment, improve thoracic extension, reduce pain and facilitate postural muscle activity and balance[26]. For example;

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

- Osteoporotic vertebral fractures are fractures of one or more of the vertebrae due to osteoporosis.Osteoporosis causes the bones to be more fragile and more likely to fracture. Osteoporotic vertebral fractures classically occur during normal day-to-day activities such as bending, twisting, walking or lifting relatively light objects.

- The pain of acute fracture usually lasts 4 to 6 weeks with intense pain at the site of fracture. Chronic pain may also occur in patients with multiple compression fractures, height loss and low bone density. Although this is probably due to structural changes or osteoarthritis.

- Vertebral fractures don't only occur due to osteoporosis. Also a trauma or metastasis can cause a vertebral fracture. The diagnosis of osteoporosis can be confirmed by Dual Energy X-ray Absorptiometry (DXA).

- Often used outcome measures to evaluate the progression of a patient are: Visual analogue scale for overall pain and pain during day and night (VAS), a Quality of Life questionnaire and a Physical functioning questionaire ( modified 23-item version of the Roland–Morris Disability Questionnaire).

- Conservative treatment (bed rest, analgesic medication, physiotherapy and bracing) still is the method of choice as medical treatment. Vertebral fractures can also be treated surgically using vertebroplasty and kyphoplasty.

- As physical therapy management there are a number of treatment approaches, including strengthening exercise, stabilisation exercise, balance training, stretching, relaxation techniques, manual therapy and taping.

Key Research[edit | edit source]

The following articles are key evidence pieces for physical therapy interventions:

- Exercise interventions to reduce fall-related fractures and their risk factors in individuals with low bone density: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials[28]

- A multi-component exercise regimen to prevent functional decline and bone fragility in home-dwelling elderly women: a randomized, controlled trial [29]

- Positive effects of exercise on falls and fracture risk in osteopenic women[30]

- Reducing the risk of falls through proprioceptive dynamic posture training in osteoporotic women with kyphotic posturing: a randomized pilot study

- Identifying osteoporotic vertebral fracture[31]

- Position Statement of the Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research[31]

Resources[edit | edit source]

www.nhs.uk/conditions/Osteoporosis/Pages/Introduction.aspx

www.nos.org.uk/about-osteoporosis

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Yoo JH, Moon SH, Ha YC, Lee DY, Gong HS, Park SY, Yang KH.Osteoporotic Fracture: 2015 Position Statement of the Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research.J Bone Metab. 2015 Nov;22(4):175-81. 30. Level of Evidence: 2B.

- ↑ Donnally, Chester & Varacallo, Matthew. (2018). Fracture, Compression. Available from:https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329717392_Fracture_Compression (last accessed 22.4.2020)

- ↑ Spine live. Spinal compression fractures reasons. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LILgFAEMAbg (last accessed 12.4.2019)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Radiopedia. Vertebral compression fractures. Available from:https://radiopaedia.org/articles/osteoporotic-spinal-compression-fracture

- ↑ Pain doctor Nevada. Spinal compression fracture. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dLiOQfr4e_A&t=20s (last accessed 12.4.2019)

- ↑ Buchbinder R, Golmohammadi K, Johnston RV, Owen RJ, Homik J, Jones A, Dhillon SS, Kallmes DF, Lambert RG.Percutaneous vertebroplasty for osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture.Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Apr 30;4:CD006349. Level of Evidence: 1A.

- ↑ NOF. Osteoporosis and your spine. National Osteoporosis Foundation. http://nof.org/articles/18 (accessed 03/02/15.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Griffith JF. Identifying osteoporotic vertebral fracture. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2015 Aug;5(4):592-602. (Level of Evidence: 2C)

- ↑ El-Fiki M. Vertebroplasty, Kyphoplasty, Lordoplasty, expandable devices and current treatment of painful osteoporoticvertebral fractures.World Neurosurg. 2016 Apr 9

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Longo UG, Loppini M, Denaro L, Maffulli N, Denaro V. Conservative management of patients with an osteoporotic vertebral fracture: a review of the literature. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012 Feb;94(2):152-7. (Level of Evidence: 2A)

- ↑ Silverman SL. The Clinical Consequences of Vertebral Compression Fracture. Bone 13, S27-S31. 1992. (Level of Evidence: 3B)

- ↑ Puisto V, Rissanen H, Heliövaara M, Impivaara O, Jalanko T, Kröger H, Knekt P, Aromaa A, Helenius I. Vertebral fracture and cause-specific mortality: a prospective population study of 3,210 men and 3,730 women with 30 years of follow-up. Eur Spine J 2011 20:2181–2186 DOI 10.1007/s00586-011-1852-0.

- ↑ Diamond TH. et al. Management of Acute Osteoporotic Vertebral Fractures: A Nonrandomized Trial Comparing Percutaneous Vertebroplasty with Conservative Therapy. Am J Med. 2003;114:257–265. (Level of Evidence: 2B)

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 James Langdon et al. Vertebral compression fractures - new clinical signs to aid diagnosis. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010; 92: 163–166 (Level of evidence: 2C)

- ↑ Whitney E, Alastra AJ. Vertebral Fracture. Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK547673/ (last accessed 22.4.2020)

- ↑ Yoo JH, Moon SH, Ha YC, Lee DY, Gong HS, Park SY, Yang KH.Osteoporotic Fracture: 2015 Position Statement of the Korean Society for Bone and Mineral Research.J Bone Metab. 2015 Nov;22(4):175-81. 30. (Level of Evidence: 2B)

- ↑ Pratelli E, Cinotti I, Pasquetti P. Rehabilitation in osteoporotic vertebral fractures. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2010 7(1): 45–47.

- ↑ Barker K, Javaid MK, Newman M, Minns Lowe C, Stallard N, Campbell H, Gandhi V, Lamb S. Physiotherapy Rehabilitation for Osteoporotic Vertebral Fracture (PROVE): study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2014 15:22

- ↑ Hong AR, Kim SW. Effects of resistance exercise on bone health. Endocrinology and Metabolism. 2018 Dec 1;33(4):435-44.

- ↑ Burke TN, Franca FJR, Ferreira de Meneses SR, Pereira RMR, Marques AP. Postural control in elderly women with osteoporosis: comparison of balance, strengthening and stretching exercises. A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Rehabilitation; 26 (11): 1021-1031. 2012. (Level of Evidence: 1B)

- ↑ De Kam D, Smulders E, Weerdesteyn V, Smits-Engelsman BCM. Exercise interventions to reduce fall-related fractures and their risk factors in individuals with low bone density: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Osteoporos Int. 2009;20:2111–2125 (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Karinkanta S, Heinonen A, Sievänen H, Uusi-Rasi K, Pasanen M, Ojala K. A multi-component exercise regimen to prevent functional decline and bone fragility in home-dwelling elderly women: a randomized, controlled trial. Osteoporos Int. 2007;18:453–462. (Level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Hourigan SR, Nitz JC, Brauer SG, O'Neill S, Wong J, Richardson CA. Positive effects of exercise on falls and fracture risk in osteopenic women. Osteoporos Int. 2008;19:1077–1086. (Level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ Sinaki M, Lynn SG. Reducing the risk of falls through proprioceptive dynamic posture training in osteoporotic women with kyphotic posturing: a randomized pilot study.Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002 Apr;81(4):241-6. (Level of Evidence: 3B)

- ↑ Itoi E, Sinaki M.Effect of back-strengthening exercise on posture in healthy women 49 to 65 years of age.Mayo Clin Proc. 1994 Nov;69(11):1054-9. (Level of Evidence: 3B)

- ↑ Bautmans I, Van Arken J, Van Mackelenberg M, Mets T. Rehabilitation using manual mobilization for thoraic kyphosis in elderly postmenopauzal patients with osteoporosis. J Rehabil Med 2010, 42: 129-135. (Level of Evidence: 3B)

- ↑ John Gibbons. Try this Kinesiology Taping technique for poor posture - its incredible. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=996cC3ovLEQ[last accessed 21/4/2020]

- ↑ Liu JT et al. Balloon kyphoplasty versus vertebroplasty for treatment of osteoporotic vertebral compression fracture: a prospective, comparative, and randomized clinical study. Osteoporos Int. 2010 Feb;21(2):359-64. Level of Evidence: 1B.

- ↑ Gauthier A, Kanis JA, Jiang Y, Martin M, Compston JE, Borgström F, Cooper C, McCloskey EV. Epidemiological burden of postmenopausal osteoporosis in the UK from 2010 to 2021: estimations from a disease model. Arch Osteoporos 2011 6:179–188.

- ↑ Kim DH, Vaccaro AR. Contemporary Concepts in Spine Care: Osteoporotic compression fractures of the spine; current options and considerations for treatment. The Spine Journal. 2006 6 479–487.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 NICE. Alendronate, etidronate, risedronate, raloxifene and strontium ranelate for the primary prevention of osteoporotic fragility fractures in postmenopausal women (amended): NICE technology appraisal guidance 160. Manchester: National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2011.