Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma

Original Editors - Jen Bognich from Bellarmine University's Pathopysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Jen Bognich, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Elaine Lonnemann and Wendy Walker

Introduction[edit | edit source]

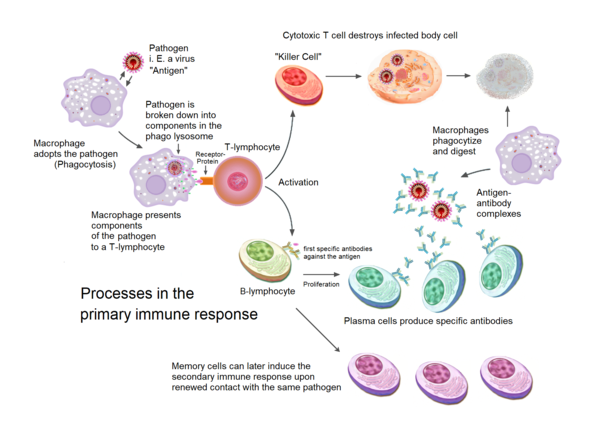

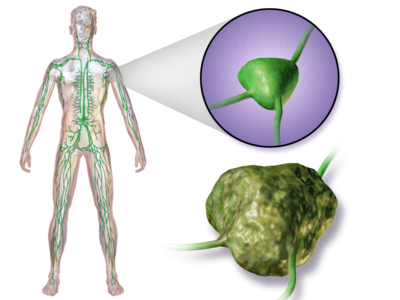

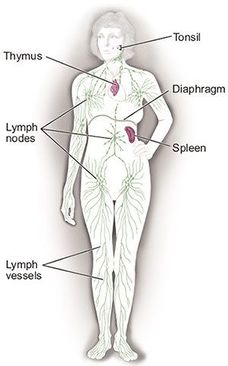

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a neoplasm of the lymphoid tissues, which originates from B cell precursors, mature B cells, T cell precursors, and mature T cells.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for about 90% of all lymphomas, and the remaining 10% are referred to as Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma comprises of various subtypes, each with different epidemiologies, etiologies, immunophenotypic, genetic, clinical features, and response to therapy. It can be divided into two groups, 'indolent' and 'aggressive' based on the prognosis of the disease.

- The most common mature B cell neoplasms are Follicular lymphoma, Burkitt lymphoma, diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Mantle cell lymphoma, marginal zone lymphoma, primary CNS lymphoma.

- The most common mature T cell lymphomas are Adult T cell lymphoma, Mycosis fungoides.

- The treatment of NHL varies greatly, depending on tumor stage, grade, and type of lymphoma, and various patient factors (e.g., symptoms, age, performance status)[1].

- Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma (NHL) [2] have a wide range of histological appearances and clinical features at presentation, which can make diagnosis difficult[3].

- Timely diagnosis is important because effective, and often curative, therapies are available for many subtypes[3].[4]

The 12 minute video below gives a summary of the condition.

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHL) may be associated with various factors, including infections, environmental factors, immunodeficiency states, and chronic inflammation.

- Various viruses have been attributed to different types of NHL.

- Epstein-Barr virus, a DNA virus, is associated with the causation of certain types of NHL, including an endemic variant of Burkitt lymphoma.

- Human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) causes adult T-cell lymphoma. It induces chronic antigenic stimulation and cytokine dysregulation, resulting in uncontrolled B- or T-cell stimulation and proliferation.

- Hepatitis C virus (HCV) results in clonal B-cell expansions. Splenic marginal zone lymphoma and diffuse large B cell lymphoma are some subtypes of NHL due to the Hepatitis C virus.

- Helicobacter pylori infection is associated with increased risk of gastric mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphomas, a primary gastrointestinal lymphoma.

- Drugs like phenytoin, digoxin, TNF antagonist are also associated with Non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Moreover, organic chemicals, pesticides, phenoxy-herbicides, wood preservatives, dust, hair dye, solvents, chemotherapy, and radiation exposure are also associated with the development of NHL.

- Congenital immunodeficiency states associated with increased risk of NHL are Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome, severe combined immunodeficiency disease (SCID), and induced immunodeficiency states like immunosuppressant medications. Patients with AIDS (Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) can have primary CNS lymphoma.

- The autoimmune disorders like sjögren syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and Hashimoto thyroiditis are associated with an increased risk of NHL. Hashimoto's thyroiditis is associate with primary thyroid lymphomas. Celiac disease is also associated with an increased risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma[1].

Epidemiolgy[edit | edit source]

- B-cell lymphomas: account for approximately 85% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States. [5]

- T-cell lymphomas: account for less than 15% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States. [5]

There are geographical variations in the incidence of individual subtypes:

- Follicular lymphoma being more common in Western countries,

- T cell lymphoma more common in Asia.

- Overall, Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is common in age 65 to 74, the median age being 67 years.

Epstein-Barr

- virus-related (endemic) Burkitt lymphoma (BL) more common in Africa

- endemic variant of Burkitt lymphoma is found in equatorial Africa and New Guinea.

- incidence of Burkitt Lymphoma in Africa is approximately 50-times higher than in the United States

- peak incidence in children is between age four to seven years, and the male: female ratio is approximately 2 to 1.

- sporadic variant of Burkitt lymphoma is seen in the United States and Western Europe.

- BL comprises 30 percent of pediatric lymphomas and <1 percent of adult non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma consists of about 7 percent of adult non-Hodgkin lymphomas in the United States and Europe with an incidence of approximately 4 to 8 cases per million persons per year. Incidence increases with age and appears to be increasing overall in the United States. The median age at diagnosis is 68 years.

- Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is the fifth most common diagnosis of pediatric cancer in children under the age of 15 years, and it accounts for approximately 7 percent of childhood cancers in the developed world.

- Lymphomas are rare in infants (≤1 percent)[1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Patients present with complaints of fever, weight loss, or night sweats, also known as B symptoms.

- Systemic B symptoms are more common in patients with a high-grade variant of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

- More than two-thirds of the patient presents with painless peripheral lymphadenopathy.

- Waxing and waning episodes of lymphadenopathy, along with other symptoms, can be seen in low-grade lymphoma.

- Enlarged lymph nodes

- Pallor

- Fatigue

- Bleeding

- Infection

- Red skin & generalized itching of unknown origin

- Pain in the chest, abdomen or bones for unknown reason[2][6][7]

Patients have different presentations and vary according to the site involved.

- Burkitt Lymphoma: Patients often have rapidly increasing tumor masses. This type of lymphoma may present with tumor lysis syndrome.

- Endemic (African) form may have a jaw or facial bone tumors in 50 to 60 percent of cases. The primary involvement of the abdomen is less common. The primary tumor can spread to extranodal sites like mesentery, ovary, testis, kidney, breast, and meninges[1].

- About 50 percent of patients may develop the extranodal disease (secondary extranodal disease), while between 10 and 35 percent of patients will have primary extranodal lymphoma at the time of diagnosis[1]. Extranodal sites of involvement may include the nasopharynx, GI tract, bone, thyroid, testes and soft tissue. Abdominal lymphoma may cause abdominal pain & fullness, GI obstruction or bleeding, ascites, back pain & leg swelling. Lymph node enlargement in the chest can lead to compression of the trachea or bronchus, causing shortness of breath & coughing.[6]

- Primary CNS lymphoma is a NHL restricted to the nervous system. Presenting symptoms may include: headache, confusion, seizures, extremity weakness/numbness, personality changes, difficulty speaking & lethargy. (Prior to the spread of HIV, this type of lymphoma was rare.)[6]

Evaluation[edit | edit source]

Workup in Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma should include the following:

- Physical Exam & History: An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient's health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.[7]

- Complete Blood Count (CBC):[7] includes the: number of red blood cells, white blood cells & platelets, amount of hemoglobin in the red blood cells, proportion of blood that is made up of RBCs

- Blood Chemistry Studies: blood sample is checked to measure the amount of certain substances released into the blood by organs & tissues in the body. An abnormal count can be associated with a sign of disease in the organ or tissue.[7]

- Lymph Node Biopsy: is viewed by a pathologist to look for cancer cells.[7]

- Bone Marrow Aspiration & Biopsy: is the removal of bone marrow, blood & a small piece of bone from the hip or breastbone.[7]

- Liver Function Tests: the blood is checked for the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). LDH levels help determine the prognosis and chance of recovery.[7]

Medications/Treatment[edit | edit source]

Treatment of Non-Hodgkin lymphoma is based on the type, stage, histopathological features, and symptoms.

- The most common treatment includes chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy, stem cell transplant, and in rare cases, surgery.

- Chemoimmunotherapy, i.e., rituximab, in combination with chemotherapy, is most commonly used.

- Radiation is the main treatment for early-stage (I, II).

- Stage II with bulky disease, stage III, and IV are treated with chemotherapy along with immunotherapy, targeted therapy, and in some cases, radiation therapy.[1]

Radiation therapy uses high energy rays to carefully and safely kill cancer cells while attempting to avoid the destruction of healthy cells. 'Radiation therapy is used to try and cure cancer, control the growth and spread of cancer and relieve symptoms, such as pain. The most common type is external beam radiation therapy, which is a series of daily outpatient treatments to accurately deliver radiation to the cancer cells. Treatment sessions usually last less than 30 minutes. Total nodal irradiation is radiation delivered to all lymph nodes in the body. Total body irradiation is radiation delivered to the entire body, usually prior to any transplants to kill all remaining cancer cells.'[8]

"Chemotherapy[9] is the use of drugs to kill cancer cells and shrink tumors. Chemotherapy drugs are designed to attack rapidly dividing cells. Therefore, the drugs are not specific to cancer cells and will also be cytotoxic to normal, noncancerous cells. Patient's experience serious side effect, often secondary to the destruction of healthy, normal, noncancerous cells. Common side effects include: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hair loss, weight loss, mouth sores, depression and leukopenia. More serious side effects include: neutropenia, anemia, peripheral neuropathy, thrombocytopenia, kidney and liver damage, tumor lysis and/or allergic reactions."[9] Common chemotherapy drugs are developed from two different agents:

- Alkylating Agent: A cytotoxic (toxic to cells) agent that inhibits cell division by reacting with DNA[9].

- Nucleosides: These inhibit DNA and RNA replication and thereby prevent cancer cells from growing[9].

There is research being done to develop a vaccination against lymphoma.[10] The vaccine itself is made by extracting cells from lymph nodes and identifying a cancer marker, called an "idiotype," that is unique to each patient. This idiotype is then fused with chemicals designed to stimulate the immune system. This vaccine have shown promising results[11] but are not able to cure anyone who currently has lymphoma or prevent anyone from developing lymphoma. The vaccination is a form of chemotherapy and has shown significant success in lengthening the time period before the cancer returns.

Prognosis[edit | edit source]

- Prognosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma mainly depends on histopathology, the extent of involvement, and patient factors.

- Patients with aggressive T- or NK cell lymphomas usually have a worse prognosis. Patients with low-grade lymphomas have increased survival which is usually 6-10 years. However, they can have the transformation to high-grade lymphomas[1].

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Types of interventions

- The physical therapy intervention that is most effective in providing an increased quality of life and improved endurance is Aerobic Exercise.

- Treadmill exercises provide cardioprotective effects on the Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity[12].

- Helping patient's maintain an active lifestyle increases their chance of survival.

- Instructions in a home exercise program (HEP) that consists of ankle range of motion, lower extremity strengthening and aerobic exercise can help them maintain normal gait mechanics and allow a quicker recovery after treatment.

- Exercise can also boost the body’s tolerance to conventional lymphoma cancer treatments, such as, chemotherapy and radiation.

- Taking part in a daily exercise program can also help the patient gain a sense of physical control over their condition, and provide a healthy outlet for stress and anxiety.

- Exercise programs that combine range of motion with other light activities like resistance training and aerobic exercise will provide positive health benefits.

- The Borg Scale of Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE) is most often used during exercise because of the limiting qualities of cancer treatments.

A Flexibility Program is often implemented to help relieve joint stiffness and pain while helping maintain good range of motion. The benefits of stretching include:

- Enhancement in performance of everyday activities

- Improvement in mobility and independence

- Improvement and maintenance in posture and muscle balance

- Injury prevention

- Promotion of physical and mental relaxation

See also Physical Activity in Cancer

The following links support the use of aerobic exercise:

- Palliative and Supportive Treatment: Randomized Control Trial[13]

- Effects of Physical Therapy on Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia.[14]

Patient Education[edit | edit source]

The patient should

- receive detailed information on all the available treatment options, adverse effects of chemotherapy, and their treatment options and prognosis

- be informed about the oncologic emergencies that may require an emergency department visit.

- be referred for psychosocial counseling, if needed

- receive education about lifestyle modifications, including smoking cessation, healthy diet, exercise, and no more than moderate alcohol consumption (shown to improve patient quality of life, risk of recurrence, and possibly mortality).

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

The differential diagnosis of Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma involves the ruling out of obvious and common conditions as well as other possible malignancies.[15]

Medical conditions mimicking symptoms similar to Non-Hodgkin lymphoma are:

- Hodgkin Lymphoma

- Epstein Barr Virus infection

- Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

- Intussusception

- Appendicitis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Metastasis from the primary tumor (e.g., nasopharyngeal carcinoma, soft tissue sarcoma)

- Malignancies or lymphoproliferative disorders like granulocytic sarcoma, multicentric Castleman disease.

- Mycobacterial and other bacterial infections causing benign lymph node infiltration and reactive follicular hyperplasia.[1]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Sapkota S, Shaikh H. Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma. InStatPearls [Internet] 2020 Jun 28. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559328/ (last accessed 31.7.2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Goodman, Snyder. Differential Diagnosis for Physical Therapists: Screening for Referral. 4th Ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2003.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Non-Hodgkin lymphoma Kate R Shankland, James O Armitage, Barry W Hancock Available from:https://redbook.streamliners.co.nz/restricted_access/Shankland%20NHL%20lancet%20review.pdf (last accessed 30.7.2020)

- ↑ Dugdale, David. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. U.S. National Library of Medicine: Medline Plus. 2010-02-23, 2010-02. Available from: (http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/000581.htm)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 American Cancer Society. Detailed Guide: Lymphoma, Non-Hodgkin Type, What is Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma? American Cancer Society, Inc.; 2009-07-17; 2010-02. Available from: (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/adult-non-hodgkins/Patient)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Goodman C.C., Fuller, K.S. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 3rd Ed. Missouri, Saunders; Elsevier; 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 National Cancer Institute. Adult Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma Treatment. 2009-09-10; 2010-02. Available from: (http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/adult-non-hodgkins/Patient)

- ↑ Radiation Oncology: Radiation Therapy for Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma. 2003-2005; 2010-03. Available from: (http://www.wehealny.org/cancer/radonc/treatment/disease/non_hodgkins.htm)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 LymphomaInfo. Non-Hodgkin's Lymphoma: Chemotherapy. 2010; 2010-03. Available from: (http://www.lymphomainfo.net/nhl/chemo.html)

- ↑ Levy, Ron. Getting the Facts: Lymphoma Vaccines. Lymphoma Research Foundation. 2008. 2010-03. Available from: (http://www.lymphoma.org/atf/cf/%7B0363CDD6-51B5-427B-BE48-E6AF871ACEC9%7D/VACCINES.PDF)

- ↑ Smith, M. Promising Results for Experimental Lymphoma Vaccine. ABC News/Health. 2009-31-05; 2010-03. Available from: (http://abcnews.go.com/Health/CancerPreventionAndTreatment/story?id=7718919&page=1)

- ↑ Yang HL, Hsieh PL, Hung CH, Cheng HC, Chou WC, Chu PM, Chang YC, Tsai KL. Early Moderate Intensity Aerobic Exercise Intervention Prevents Doxorubicin-Caused Cardiac Dysfunction Through Inhibition of Cardiac Fibrosis and Inflammation. Cancers. 2020 May;12(5):1102.

- ↑ Courneya, K., Sellar, C., Stevinson, C., McNeely, M., Peddle, C., Friedenreich, C., Tankel, K., Basi, S., Chua, N., Mazurek, A., Reiman, T. “Randomized Controlled Trial of the Effects of Aerobic Exercise on Physical Functioning and Quality of Life in Lymphoma Patients.” Journal of Clinical Oncology, Vol 27, No 27, Pgs 4605-4612. 2009-20-09; 2010-03. Available from: (http://jco.ascopubs.org/cgi/content/abstract/27/27/4605)

- ↑ Marchese, VG., Chiarello, LA., Lange, BJ. Effects of physical therapy intervention for children with actue lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatric Blood Cancer. 2004-02; 42(2):127-133. 2010-03. Available from: (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14752875)

- ↑ Nursing Link: Hodgkins Disease & Non Hodgkins Lymphoma. 2010; 2010-04. Available from: (http://nursinglink.monster.com/training/articles/332-hodgkins-disease-non-hodgkins-lymphoma)