Mindfulness for Clinicians

Original Editor - Merinda Rodseth based on the course by Shrey Vazir

Top Contributors - Merinda Rodseth, Kim Jackson, Jess Bell, Tarina van der Stockt and Ewa Jaraczewska

Introduction[edit | edit source]

“You cannot pour from an empty cup” - Dalai Lama

Looking after the health of people brings great rewards, but also comes with significant challenges.[1] There are many sources of stress for clinicians, both external (heavy patient load, time restraints, interpersonal staff conflict, record-keeping requirements, financial concerns) as well as internal stressors (personality characteristics, perfectionism, poor emotional regulation, harsh self-judgement, trauma).[1][2][3] The stress experienced by healthcare professionals (HCP) can be mostly attributed to their continued exposure to complex and emotionally tense situations, closely related to the pain and suffering of the patients they attend as well as the strong emotions from both themselves and their patients.[3][4][5] High levels of stress ultimately leads to symptoms of burnout, physical illness, compassion-fatigue and ultimately an inability to provide proper care to patients.[1] These factors have spurred great interest in the emotional well-being of HCPs with the objective of enabling HCPs to cope with the challenges they face on a daily basis and effectively manage their stress and emotions.[2][4][6]

Benefits of Mindfulness for Clinicians[edit | edit source]

Following the efficacy of mindfulness for patients, interest has grown for mindfulness in healthy individuals especially in healthcare and in a workplace setting.[3] Mindfulness is viewed as particularly suited for clinician burnout as it is non-religious yet addresses purpose and meaning, has a solid scientific background and has secular and academic appeal.[7] The benefits of mindfulness for HCPs have been shown to include: [2][4][8][9][10][11]

- Stress reduction

- Improved mood

- Increased resilience

- Increased self-compassion

- Improved self-efficacy

- Increased empathy

- Reduced burnout

- Reduced compassion fatigue

- Improved well-being

Three of these benefits will be further explored as they are of particular importance for the well-being of clinicians. These include:

1. Increased resilience[edit | edit source]

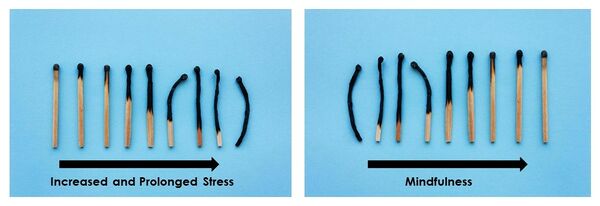

Resilience can be defined as “a personal trait that helps individuals cope with adversity and achieve good adjustment and development during trying circumstances” or “the capacity to maintain or recover high well-being in the face of life adversity”[12]. Resilience is proposed as a skill that “inoculates individuals against the impact of adversity and traumatic events” (Bajaj 2015).[12] Resilience is essentially our bounce-back ability. Individuals who are more mindful, have also been found to possess greater resilience and improved life-satisfaction.[12] It is postulated that the awareness and acceptance aspects of mindfulness foster the development of greater resilience which in turn lead to greater well-being.[12] Mindfulness also has the potential to cultivate resilience in that it enables individuals to respond to difficult situations without reacting in an automatic and non-adapting way, but rather with non-judgemental openness.[12] Mindful individuals can, therefore, better cope with difficult thoughts and emotions without getting overwhelmed by them and shutting down. Resilience is further proposed to act as a buffer against the negative impact of stress and thereby protect against burnout.[13]

2. Improved self-compassion[edit | edit source]

“Caring for others requires caring for oneself” - Dalai Lama

Compassion for others has been linked to self-compassion and is vital for the prevention of compassion fatigue and the promotion of compassionate patient care.[6] Compassion involves “being receptive to and affected by the suffering of others, such that one desires to alleviate their suffering” [14]. Self-compassion refers to directing compassion inwards and applying it to one’s own experiences.[4][14] Many individuals tend to be self-critical and ruminative during times of hardship, pain or failure when self-compassion could be more beneficial.[14] Self-compassion, as a form of self-acceptance, consists of three bipolar components: [14]

- Self-kindness vs self-judgement. Self-kindness involves treating oneself with kindness, empathy and forgiveness instead of harsh judgement.

- Common humanity vs isolation. Common humanity acknowledges that negative experiences are a natural and unavoidable part of any human life and connects us to others, alleviating feelings of isolation.

- Mindfulness vs over-identification. Mindfulness enables individuals to acknowledge and learn from painful thoughts and feelings, thereby reducing avoidance and over-identification.

Mindfulness cultivates self-compassion which in turn leads to greater life satisfaction, and lower levels of stress and anxiety, perfectionism, rumination and depression.[4][14] Self-compassion can also enhance resilience by regulating emotional responses to distressing situations.[14]

3. Enhanced stress management and burnout prevention[edit | edit source]

Mindfulness has been shown to improve stress management and reduce burnout in clinicians.[5][9] Burnout can be defined as “a syndrome resulting from exposure to chronic interpersonal stressors on the job with key symptoms including overwhelming exhaustion (loss of energy, depletion, debilitation, and fatigue), depersonalisation (negative or inappropriate attitudes towards clients, irritability, loss of idealism and withdrawal), and a sense of ineffective and lack of accomplishment (reduced productivity or capability, low morale, and inability to cope)”[9]. During times of stress, clinicians tend to work harder and the prolonged and chronic exposure to stress results in burnout.[15] Mindfulness provides an alternative strategy to clinicians:[15]

- Increased awareness of their stress, emotions and needs

- Enhanced self-regulation, and

- Improved self-reflection on their behaviours and clinical practice.

A detailed discussion of burnout is available here.

Clinicians who practise mindfulness also report lower levels of stress and fewer symptoms of burnout.[15]

Brief Mindfulness-Based Interventions[edit | edit source]

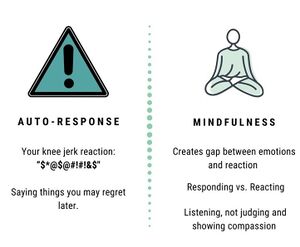

The purpose of mindfulness programmes is to train individuals to respond to situations in a reflective way as opposed to responding automatically.[4] Mindfulness provides a space or a gap between the initial emotional reaction and the eventual behaviour/response. The gap created by mindfulness is vital for the response.[9] Research has shown that resilience can be enhanced and burnout limited through skills that allow individuals to gain some distance from negative emotions, develop some positive ones, and focus attention in the present moment.[9] Fortunately, mindfulness can be practised in any setting and in a variety of ways and even brief mindfulness-based interventions have been shown to be effective.[9]

One example is the STOP technique, which is simple and short and has an easily remembered acronym:[16]

S = Stop for a moment and pause

T = Take 3-5 slow, deep and long breaths - reconnect with your body

O = Observe your thoughts, emotions and body sensations

P = Proceed mindfully with your day, without judging your thoughts, emotions or sensations

The STOP practice facilitates an individual's ability to create a “gap” between the stimulus and the response, which is useful for avoiding a spontaneous response that could have negative consequences.[16] With increased awareness of beliefs, emotions and body sensations that point to a situation being more challenging, one can pause and choose a more appropriate way to proceed.[2] The STOP practice can easily be incorporated:

- Before engaging in difficult conversations (with patients, their families, a manager, a colleague)

- In between clients/patients - to “reset” before starting with the next patient

- In day-to-day mundane tasks such as cleaning equipment, hand-washing, etc.

Other practical mindfulness applications include:[5][9]

- Mindful walking[18]

- Walk at a slower pace of approximately one step per second

- Be aware of the present moment experiences

- Pay attention to the rhythm of your breathing

- Stay attentive to the movement of your steps

- Identify your body sensations and feelings arising from present moment

- Mindful breathing

- Breathing-based meditations

- Box breathing

- 4-7-8 breathing

- Mindful movement (yoga)

- Listen to and increase awareness of your body.

- Find something about your body to enjoy. It can be your breathing or movement of your arms.

- Become aware of your posture during gentle movements and stretching.

- Body scan

- Mental scanning of your body

- Pay attention to parts of your body and bodily sensations

- Follow gradual sequence from feet to head

- You can find example of body scan practice here

- Mini meditation exercises[19]

- Five repetitions of deep inhalation and exhalation

- Slowly count one to ten, each breath per number

- Add stretching or yoga posture to breathing awareness

- Imagine a scene in nature or picture yourself surrounded by nature

- Focus you attention to the sounds around you

Key Reminders about Mindfulness[edit | edit source]

Mindfulness:

- is grounded in science, not just some mystique hokey pokey practice

- is a tool to empower our patients to self-manage their conditions

- can help to reduce symptoms of stress, depression and pain

- can be an effective approach to the management of chronic pain

- can enhance stress management, improve self-compassion and prevent burnout

- promotes calmness and resilience in the face of adversity

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Hedderman E, O’Doherty V, O’Connor S. Mindfulness moments for clinicians in the midst of a pandemic. Irish journal of psychological medicine. 2020 May 21:1-4. doi:10.1017/ipm.2020.59

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Dobkin PL, Bernardi NF, Bagnis CI. Enhancing clinicians' well-being and patient-centered care through mindfulness. Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions. 2016 Jan 1;36(1):11-6. DOI: 10.1097/CEH.000000000000002

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Janssen M, Heerkens Y, Kuijer W, Van Der Heijden B, Engels J. Effects of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction on employees’ mental health: A systematic review. PloS one. 2018 Jan 24;13(1):e0191332.DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191332

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Ruiz‐Fernández MD, Ortíz‐Amo R, Ortega‐Galán ÁM, Ibáñez‐Masero O, Rodríguez‐Salvador MD, Ramos‐Pichardo JD. Mindfulness therapies on health professionals. International journal of mental health nursing. 2020 Apr;29(2):127-40. DOI:10.1111/inm.12652

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Pappous A, Mohammed WA, Sharma D. Physiotherapists’ experiences with a four-week mindfulness-based stress reduction program. European Journal of Physiotherapy. 2020 Apr 6:1-6. DOI: 10.1080/21679169.2020.1745272

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Raab K. Mindfulness, self-compassion, and empathy among health care professionals: a review of the literature. Journal of health care chaplaincy. 2014 Jul 1;20(3):95-108. DOI:10.1080/08854726.2014.913876

- ↑ Fortney L, Luchterhand C, Zakletskaia L, Zgierska A, Rakel D. Abbreviated mindfulness intervention for job satisfaction, quality of life, and compassion in primary care clinicians: a pilot study. The Annals of Family Medicine. 2013 Sep 1;11(5):412-20. DOI:10.1370 /af m.1511.

- ↑ Spinelli C, Wisener M, Khoury B. Mindfulness training for healthcare professionals and trainees: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 2019 May 1;120:29-38. DOI:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2019.03.003

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 Nguyen MC, Gabbe SG, Kemper KJ, Mahan JD, Cheavens JS, Moffatt-Bruce SD. Training on mind-body skills: Feasibility and effects on physician mindfulness, compassion, and associated effects on stress, burnout, and clinical outcomes. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2020 Mar 3;15(2):194-207. DOI:10.1080/17439760.2019.1578892

- ↑ Leonard HD, Campbell K, Gonzalez VM. The relationships among clinician self-report of empathy, mindfulness, and therapeutic alliance. Mindfulness. 2018 Dec;9(6):1837-44. DOI: 0.1007/s12671-018-0926-z

- ↑ Shapiro SL, Astin JA, Bishop SR, Cordova M. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for health care professionals: results from a randomized trial. International journal of stress management. 2005 May;12(2):164.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 Bajaj B, Pande N. Mediating role of resilience in the impact of mindfulness on life satisfaction and affect as indices of subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences. 2016 Apr 1;93:63-7. DOI:10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.005

- ↑ Hwang WJ, Lee TY, Lim KO, Bae D, Kwak S, Park HY, Kwon JS. The effects of four days of intensive mindfulness meditation training (Templestay program) on resilience to stress: a randomized controlled trial. Psychology, health & medicine. 2018 May 28;23(5):497-504. DOI:10.1080/13548506.2017.1363400

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 14.5 Fong M, Loi NM. The mediating role of self‐compassion in student psychological health. Australian Psychologist. 2016 Dec 1;51(6):431-41. DOI: 10.1111/ap.12185

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Scheepers RA, Emke H, Epstein RM, Lombarts KM. The impact of mindfulness‐based interventions on doctors’ well‐being and performance: A systematic review. Medical education. 2020 Feb;54(2):138-49. DOI:10.1111/medu.14020

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Liao Y, Wang L, Luo T, Wu S, Wu Z, Chen J, Pan C, Wang Y, Liu Y, Luo Q, Guo X. Brief mindfulness-based intervention of ‘STOP (Stop, Take a Breath, Observe, Proceed) touching your face’: a study protocol of a randomised controlled trial. BMJ open. 2020 Nov 1;10(11):e041364. DOI: i:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-041364

- ↑ AboutKidsHealth. STOP for Minfulness. Published 26 Nov 2019. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GgBVIZAEQqU&t=43s [last accessed 14 May 2021]

- ↑ Yang CH, Hakun JG, Roque N, Sliwinski MJ, Conroy DE. Mindful walking and cognition in older adults: A proof of concept study using in-lab and ambulatory cognitive measures. Prev Med Rep. 2021 Jul 14;23:101490.

- ↑ The Mini (adapted from Benson Henry Institute). Available from https://sageintegrativemedicine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/The-Mini.pdf [last access 23.10.23]