Mindful Learning in the Digital World

Original Editor - Ewa Jaraczewska based on course by Shrey Vazir

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska, Jess Bell, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson and Tarina van der Stockt

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Mindfulness is "awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment". Dr Jon Kabat-Zinn[1]

Many definitions of mindfulness exist and they present a wide range of concepts.[2] It has been described as a skill developed via practice (e.g. meditation)[3] and as a psychological process. Harvard University psychology professor, Dr Ellen Langer, defines mindfulness as follows: "the process of actively noticing new things. When you do that, it puts you in the present [...] It’s the essence of engagement".[4] According to Dr Langer, approaching learning this way promotes engagement and mind-openness, results in better performance and allows the learner to focus on the present while using experiences from the past.[4][5]

Digital learning is "any type of learning that is accompanied by technology or by instructional practice that makes effective use of technology."[6] Digital learning demonstrates great educational potential.[7] It enables interactions that closely approximate the interactions that occur in the real world.[7]

Mindfulness and Mindlessness[edit | edit source]

The word mindfulness translates as "lucid awareness" and it originates from the Pali Canon, the oldest complete collection of Buddhist texts.[8] In this text, mindfulness means attending to the facts without commenting on them. In modern psychological studies, it is described as paying attention to current information without judgment.[9] Mindfulness is a state of mind - of conscious awareness and openness.[10] Mindful learning means focusing on the present moment in each learning situation and absorbing what is happening as it happens.[1]

Benefits associated with mindfulness include:

- Making it easy to pay attention and notice subtle changes in reality[5]

- Allowing individuals to remember more about what has been done[4][1]

- Promoting creativity[4]

- Allowing individuals to take advantage of opportunities when they present themselves[4]

- Generating more positive results[4]

- Improving attention[1]

- Allowing individuals to focus on the things that matter the most[1]

- Improving problem-solving[1]

- Helping to reduce anxiety[11]

- Decreasing stress[12]

- Improving sleep

- Improving pain management outcomes in chronic pain populations[13]

Mindlessness is the opposite state of mind to mindfulness. It relies on experiences from the past; it is like a habit where individuals rely on automatic processing.[10] Mindless learning is a passive type of learning.[1] For example, someone may attempt to take an online course and absorb the information while checking emails, cooking, or finishing a progress note from their day's workload.[1] Individuals think and react to the new information without really considering the present context. When they are exposed to new information, they tend to assume that the information is obvious, so there is no point in learning it.[1]

Brain Networks[edit | edit source]

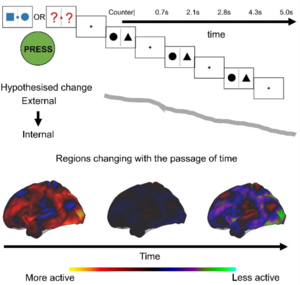

There are two competing networks in the brain that work to regulate a person's focus and attention.[1] The first network is called the default mode network (DMN) and it generally exhibits higher activity at rest.[14] The second network is called the task-positive network (TPN). This network is more active during tasks when the person is very engaged and attentive.[1]

Default Mode Network (DMN)[edit | edit source]

DMN is distributed in the posteromedial/inferior parietal, temporal, and lateral/ medial prefrontal cortex. These regions are furthest away from those contributing to sensory and motor systems.[15][16] These regions show higher activity at rest and decreased activity during attention-demanding tasks.[14] Some research indicates that DMN can be active in goal-directed tasks, but these tasks must require the use of internally directed cognition.[14]

DMN is activated when a person is not focused on the outside world, but on their internal mental-state processes.[17] It is active for 47% of the time and is responsible for daydreaming, thinking about the future, the past, and ignoring the present moment.[1]

Task-Positive Network (TPN)[edit | edit source]

The task-positive network (TPN) is required to process external objects. It is more active during tasks that require attention.[18] Externally oriented attention decreases activation in the DMN and increases activation in the TPN. The task-positive network was also found to have a correlation with response preparation and selection.[18]

When self-focus and lack of attention to the environment are present (e.g. in conditions such as depression and social anxiety), increased activation of the DMN over the TPN is observed.[19] Meditation practices that focus attention on the immediate experience may have the opposite effect, causing a decrease of DMN activity and an increase of TPN activity.[19] Research has shown that the practice of mindfulness meditation helps to facilitate activation of the TPN and reduces activity of the DMN.[1]

Distractions and Mind-Wandering[edit | edit source]

Distraction is “the process of interrupting attention” and “a stimulus or task that draws attention away from the task of primary interest.”[20] Because of the distraction, individuals are not able to stay focused on the things they want to do.

Example of distractions:

- Looking at notifications on your phone while having a conversation

- Checking emails while listening to a webinar

- Scrolling through social media when planning to read a book[21]

External World Distraction[edit | edit source]

External distractions come from our environment. They include:

- Prompts to check mail, answer a text or read an alert

- Interruption from a coworker when you are in the middle of doing work

- The presence of an object eg. television in an office[21]

Hugo Gernsback, a science fiction writer and inventor was a pioneer in this field, attempting to remove external distractions to help people study more efficiently.[1] Gernsback discovered that sound was the biggest distractor and developed the "Isolator" to help students focus on the book they were reading or the paper they had to write. The Isolator was a helmet that covered a person's entire head; it even required a breathing tube attached to an oxygen tank.[22] While the idea was great, the product was not popular because the helmet was too heavy.

Auto-Pilot Mode of Living[edit | edit source]

When a person is on autopilot, their brain shows activity in the default mode network zones.

The autopilot mode of living allows a person to undertake tasks without thinking about them. The average person spends 47% of their time in the autopilot mode of living.[1] This is because it is simply too difficult to live every moment completely engaged and aware. Autopilot is a "state of mind in which a person acts without conscious intention or awareness of present moment".[23] When a person is on autopilot, they are daydreaming, their mind wanders, they are planning for the future, regretting the past, or just narrating their lives.[1] There is no focus and no attention, and it comes with a cognitive cost as it leads to distraction from what is really important.[1] Autopilot can become harmful because it affects an individual's emotional experience.[24]

Mindlessness is defined as an autopilot mode of learning, where individuals think and react to a piece of new information without considering the present context.[1]

Practical Applications of Mindful Learning[edit | edit source]

The activity rest cycle (or the ultradian performance rhythm) is a key concept of performance. It includes creating structure, taking breaks and mind-wandering.[1]

Suggestions to improve focus, memory, and attention in an individual's day-to-day life:[1]

- Create a structure: Structuring tasks and learning allows us to spend more time on things that matter.

- Take regular breaks to recharge and restore energy: As a general rule, people work best when they work for a continuous period of 90 minutes, followed by a 20-minute break. The goal is to find an ideal amount of focused attention and a break time.

- Schedule time for mind-wandering to improve one's focus: Allow time to check emails and social media and do whatever you need to do. According to Paul Seli,[26] intentionally pausing to think about something unrelated to the task at hand, can boost focus when a person returns to the original task.[26][1]

- Practise meditation to improve focus: Take the following steps:[1]

- Step 1: Set aside a dedicated amount of time

- Step 2: Find a comfortable position

- Step 3: Close your eyes or keep a soft gaze

- Step 4: Choose an anchor (breath, sound, or touch) that resonates with you or that you relate to

- Step 5: Focus on this chosen anchor

- Step 6: When your mind starts wandering, return back to the anchor

- Practise mindfulness through:

- Formal practice (meditation)

- Informal practice (performing everyday activities fully focused)

- Mini mindfulness exercises:

- Mindful body scan: examining different sensations in your body, starting from your feet to the top of your head and noticing different areas that might be tense, stiff, or in pain, or that might be uncomfortable

- The power of the pause (STOP): Stop for a moment and pause, Take three breaths, slow, Observe your thoughts, emotions, and sensation, Proceed

- Grounding with the five senses: notice mentally or physically five things you can see, four things you can touch, three things you can hear, two things you can smell, and one thing you can taste

- Box breathing: visualisation of a box with four edges: inhale, hold, exhale, hold

- Mindful walking or performing any mindful movement in any sense.[1]

Summary[edit | edit source]

- Sustaining attention is becoming more and more difficult

- Specific brain networks associated with mind-wandering and attention can be targeted with different exercises, such as mindfulness or meditation

- Concepts of mindfulness and mindful learning help to improve focus and reduce mind-wandering

- There are cognitive benefits associated with mindfulness

- Avoid multitasking because it divides attention

- Allow yourself to focus on one task at a time, one problem at a time, or in the grander scheme of things focus on one day at a time

- There are evidence-based techniques that can rewire our brain, activate the task-positive networks, and reduce activity in the default mode network[1]

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Learn how to avoid distraction in a world that is full of it. NIR and FAR. Available from: https://www.nirandfar.com/distractions/

- Mindfulness Muse: https://www.mindfulnessmuse.com/blog

- Meditation: https://www.aurahealth.io

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 1.18 1.19 1.20 1.21 1.22 1.23 Shrey Vasir. The Power of Mindful Learning in the Digital World. Physiopedia 2022.

- ↑ Van Dam NT, van Vugt MK, Vago DR, Schmalzl L, Saron CD, Olendzki A, Meissner T, Lazar SW, Kerr CE, Gorchov J, Fox KCR, Field BA, Britton WB, Brefczynski-Lewis JA, Meyer DE. Mind the Hype: A Critical Evaluation and Prescriptive Agenda for Research on Mindfulness and Meditation. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2018 Jan;13(1):36-61. doi: 10.1177/1745691617709589. Epub 2017 Oct 10. Erratum in: Perspect Psychol Sci. 2020 Sep;15(5):1289-1290.

- ↑ Davis DM, Hayes JA. What are the benefits of mindfulness? A practice review of psychotherapy-related research. Psychotherapy (Chic). 2011 Jun;48(2):198-208.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 4.5 Mindfulness in the Age of Complexity. Harvard Business Review, March 2014. Available at: https://hbr.org/2014/03/mindfulness-in-the-age-of-complexity (last accessed: 01.04.2022)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Davenport C, Pagnini F. Mindful Learning: A Case Study of Langerian Mindfulness in Schools. Front Psychol. 2016 Sep 12;7:1372.

- ↑ Digital Learning. Wikipedia Foundation, 08 January 2022. Available at:https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Digital_learning. [last accessed 01.04.2022].

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gisbert M, Bullen M. Teaching and Learning in Digital World. Strategies and Issues in Higher Education. Publicacions Universitat Rovira i Virgili, Tarragona (Spain), 2015.

- ↑ Bodhi B. What does mindfulness really mean? A canonical perspective. Contemporary Buddhism, 2011;12(1):19-39.

- ↑ Kabat-Zinn J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 2003;10(2): 144–156.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Langer EJ. Matters of mind: Mindfulness/mindlessness in perspective. Consciousness and cognition. 1992 Sep 1;1(3):289-305.

- ↑ Hofmann SG, Sawyer AT, Witt AA, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2010 Apr;78(2):169-83.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 NourPoundation. How Does Mindfulness Reduce Stress? 2013 Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DKOGuQJCxr8[last accessed 02/04/2022]

- ↑ Creswell JD, Lindsay EK, Villalba DK, Chin B.Mindfulness Training and Physical Health: Mechanisms and Outcomes. Psychosomatic Medicine 2019; 81(3): 224

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Zhang R, Volkow ND. Brain default-mode network dysfunction in addiction. Neuroimage. 2019 Oct 15;200:313-331.

- ↑ Smallwood J, Bernhardt BC, Leech R, Bzdok D, Jefferies E, Margulies DS. The default mode network in cognition: a topographical perspective. Nat Rev Neurosci 2021; 22: 503–513.

- ↑ Alves PN, Foulon C, Karolis V, Bzdok D, Margulies DS, Volle E, Thiebaut de Schotten M. An improved neuroanatomical model of the default-mode network reconciles previous neuroimaging and neuropathological findings. Commun Biol. 2019 Oct 10;2:370.

- ↑ Ekhtiari H, Nasseri P, Yavari F, Mokri A, Monterosso J. Neuroscience of drug craving for addiction medicine: From circuits to therapies, Chapter 7. Editor(s): Hamed Ekhtiari, Martin Paulus. Progress in Brain Research, Elsevier 2016; 223:115-141.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Qiao L, Luo X, Zhang L, Chen A, Li H, Qiu J. Spontaneous brain state oscillation is associated with self-reported anxiety in a non-clinical sample. Scientific Reports. 2020 Nov 12;10(1):1-1.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Knyazev GG, Savostyanov AN, Bocharov AV, Levin EA, Rudych PD. Iintrinsic connectivity networks in the self-and other-referential processing. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 2020 Nov 10;14:460.

- ↑ “Distraction” (n.d.) In APA Dictionary of Psychology. Available from: https://dictionary.apa.org/distraction. [last accessed 02.04.2022].

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Learn how to avoid distraction in a world that is full of it. NIR and FAR. Available from: https://www.nirandfar.com/distractions/[last accessed 02.04.2022]

- ↑ Tapalaga A. The Vintage Isolation Helmet. The Isolator by Hugo Gernsback. Available from: https://historyofyesterday.com/the-vintage-isolation-helmet-a5a39a8a9d27. Dec 11, 2020. [last accessed 02.04.2022]

- ↑ Crane R. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy: Distinctive features. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, 2009.

- ↑ Schenck L.Pros & Cons of Being on “Automatic Pilot. Available from:https://www.mindfulnessmuse.com/mindfulness/pros-and-cons-of-being-on-automatic-pilot. [last accessed 02.04.2022]

- ↑ Lewis Psychology. Autopilot Mode, the Brain and Mindfulness (The Default Mode Network). 2021. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNicQ1i6dz4[last accessed 02/04/2022]

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Seli P, Risko EF, Smilek D, Schacter DL. Mind-Wandering With and Without Intention. Trends Cogn Sci. 2016 Aug;20(8):605-617.

- ↑ Headspace | Mini Meditation | Let Go of Stress . 2018. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c1Ndym-IsQg [last accessed 02/04/2022]

- ↑ Sunnybrook Hospital. Box breathing relaxation technique: how to calm feelings of stress or anxiety. 2020. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tEmt1Znux58 [last accessed 02/04/2022]