Masseter

Description[edit | edit source]

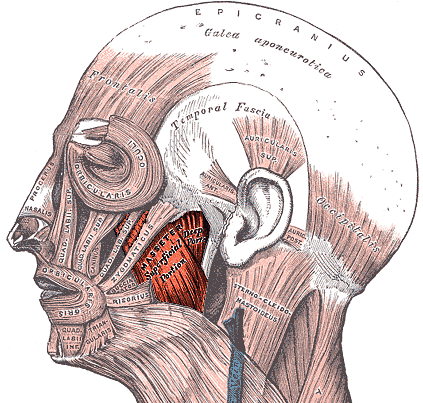

The masseter a primary muscle of mastication and it is one of the strongest of human muscles. It is responsible for the elevation of the mandible and some protraction[1], and also the chewing movement of the mandible at the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). It is a powerful superficial quadrangular muscle that originates from the zygomatic arch and inserts along the angle and lateral surface of the mandibular ramus. In this article, we will explore the anatomy, origin, insertion, and function of the masseter muscle, as well as its role in jaw pain and dysfunction, and therapeutic interventions.

Origin[edit | edit source]

The masseter muscle originates from the zygomatic arch and maxillary process of the zygomatic bone[2] and it has a superficial and deep part:

- The superficial portion of the masseter muscle originates from a thick aponeurosis on the temporal process of the zygomatic bone and the anterior two-thirds of the inferior border of the zygomatic arch.

- The deep portion of the masseter muscle originates from the posterior third of the inferior border of the zygomatic arch and the zygomatic process of the maxilla.

The fibers of the superficial and deep heads are continuous at their insertion. The masseter muscle has a quadrangular shape appearance on gross examination due to its origins and insertions.

Insertion[edit | edit source]

The muscle fibers converge inferiorly, forming a tendon that inserts onto the outer surface of the mandibular ramus and coronoid process of the mandible[1]. The intermediate and deep muscle fibers of the masseter muscle function to retract the mandible, while the superficial fibers function to protrude the mandible.

Nerve[edit | edit source]

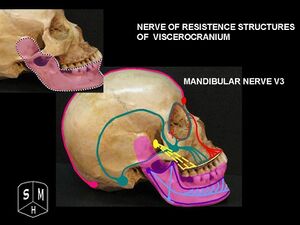

The masseter muscle is innervated by the masseteric nerve, which is a branch of the mandibular nerve (V3) of the trigeminal nerve[2]. The mandibular nerve is the third branch of the trigeminal nerve and carries both sensory and motor fibers. The masseteric nerve crosses the mandibular notch to reach the masseter muscle. The motor fibers of the masseteric nerve supply the masseter muscle, allowing it to contract and perform its primary function of elevating the mandible and some protraction. The sensory fibers of the mandibular nerve provide sensation to the lower teeth, gums, and lip, as well as the skin of the chin and lower jaw.

Artery[edit | edit source]

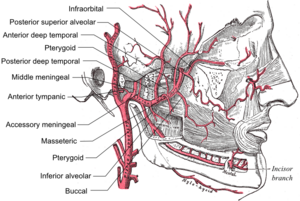

The masseter muscle primarily receives its vascular supply from the masseteric artery, which is a a small vessel, branch of the maxillary artery[2]. The maxillary artery is a branch of the external carotid artery and supplies deep structures of the face. The masseter muscle also receives blood supply from the facial artery[3].

Function[edit | edit source]

The masseter muscle is one of the primary muscles of mastication, responsible for the elevation of the mandible and some protraction. The masseter muscle works in conjunction with two other jaw-closing muscles, the temporalis and the medial pterygoid, to close the jaw.

The major function of the masseter muscle is to elevate the jaw bone, bringing the teeth together in the chewing motion[2]. The superficial part of the masseter muscle functions to move the mandible or lower jaw forward, bringing the lower front teeth in front of the upper front teeth.

In addition to elevating the mandible and causing a powerful jaw closure, the masseter also is responsible for the protrusion movement, in other words, to move the mandible forward through the contraction of its superior part.

Clinical relevance[edit | edit source]

The masseter muscle plays a significant role in temporomandibular disorders (TMD), which are disorders of the jaw muscles, temporomandibular joints, and the nerves associated with chronic facial pain[4]. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is where the mandible (the lower jaw) and the temporal bone (the side and base of the skull) meet and slide and rotate in front of each ear; the masseter muscle also plays a role in stabilizing the TMJ when you clench your teeth.

Dysfunction of the masseter muscle can result in pain, difficulty chewing, or swelling around the jaw and face, which can lead to TMD. In more serious cases this dysfunction can lead to difficulty speaking. The lateral pterygoid muscle, which is one of the muscles of mastication, can also play a significant role in TMD cases. As detailed below, physiotherapy treatment for TMD may include manual therapy techniques such as trigger point release, massage, and stretching, as well as exercises to improve range of motion of the jaw.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

The masseter muscle can be assessed through a variety of techniques in a physiotherapy context. The most common technique is palpation, involving feeling the muscle for any areas of tenderness, swelling, or trigger points, which are areas of muscle that are hyperirritable and can cause pain and discomfort.

Another technique is manual muscle testing, which involves assessing the strength and function of the masseter muscle. In addition, electromyographic activity in the masseter muscle can be analyzed to assess the influence of temporomandibular disorder (TMD) on muscle function.

The jaw jerk reflex[5], also known as the masseter or mandibular reflex, can also be tested as part of a routine neurological examination that assesses the status of a patient's trigeminal nerve (cranial nerve V). It can distinguish an upper cervical cord compression from lesions that are above the foramen magnum. The mandible, or lower jaw, is tapped at a downward angle just below the lips at the chin while the mouth is held slightly open. In response, the masseter muscles will jerk the mandible upwards1.

Normally, this reflex is absent or very slight. However, in individuals with upper motor neuron lesions, the jaw jerk reflex can be quite pronounced. The jaw jerk reflex can be classified as a dynamic stretch reflex, with sensory neurons of the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus sending axons to the trigeminal motor nucleus, which in turn innervates the masseter. The jaw jerk reflex can be tested as part of a routine neurological examination and can provide valuable information about the status of the trigeminal nerve and the upper motor neurons.

Treatment[edit | edit source]

There are several conventional interventions available for physiotherapy of the masseter muscle dysfunctions, including therapeutic exercise and manual therapy. Therapeutic exercise involves specific exercises that aim to increase the flexibility of the muscles involved in jaw movement; manual therapy aims ischaemic compression by applying pressure to a specific point in the muscle to decrease muscle tension and alleviate pain. In addition to these conventional methods, some unconventional interventions are also possible, such as dry needling. Dry needling involves inserting a thin needle into the trigger point of the muscle to relieve pain and improve function. All techniques can be combined to achieve the best outcomes for patients with masseter muscle dysfunctions.

A randomized controlled trial[6] compared the effects of exercise combined with ischaemic compression and exercise alone on patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMDs). Fifty patients were randomized into two groups, with Group 1 receiving ischaemic compression in addition to exercise, and Group 2 receiving exercise alone. Results showed that both groups had similar effects on range of motion, pain, pain pressure threshold, and functionality at weeks 1 and 4, except for the painless mouth opening and maximum assisted mouth opening values, which were higher in Group 1 at week 1. The study concludes that exercise combined with ischaemic compression and exercise alone have similar effects on patients with TMDs.

Examples of exercises for TMD pain relief are shown in the video below.

A RCT study[7] from 2010 aimed to investigate the effects of dry needling on the masseter muscle trigger points in patients with temporomandibular disorders (TMD). The study involved 12 female patients diagnosed with myofascial TMD, who received either deep dry needling or sham dry needling at the most painful point on the masseter muscle trigger point. The results of the study showed that deep dry needling led to significant improvements in pressure pain threshold, mandibular condyle, and pain-free active jaw opening. The researchers concluded that dry needling can be an effective treatment for myofascial TMD, as it improves the pain threshold and jaw function in patients.

An illustration of dry needling techniques on a TMD physical therapy patient is shown in the video below.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Gil-Martínez A, Paris-Alemany A, López-de-Uralde-Villanueva I, La Touche R. Management of pain in patients with temporomandibular disorder (TMD): challenges and solutions. J Pain Res. 2018;11:571-587. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S127950. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5859913/

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Corcoran NM, Goldman EM. Anatomy, head and neck, masseter muscle. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539869/

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Drake RL, Vogl AV, Mitchell AWM. Gray’s Anatomy for Students. 3rd ed. Churchill Livingstone; 2015. p. 977-979.

- ↑ Facial Artery. ScienceDirect. [updated 2021 Mar 19]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/medicine-and-dentistry/facial-artery

- ↑ Gil-Martínez A, Paris-Alemany A, López-de-Uralde-Villanueva I, La Touche R. Management of pain in patients with temporomandibular disorder (TMD): challenges and solutions. J Pain Res. 2018;11:571-587. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S127950. Available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5859913/

- ↑ Jaw Jerk Reflex. ScienceDirect. [updated 2021 Mar 26; cited 2023 Apr 22]. Available from: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/neuroscience/jaw-jerk-reflex

- ↑ Şahin D, Kaya Mutlu E, Şakar O, Ateş G, İnan Ş, Taşkıran H. The effect of the ischaemic compression technique on pain and functionality in temporomandibular disorders: A randomised clinical trial. J Oral Rehabil. 2021 May;48(5):531-541. doi: 10.1111/joor.13145. Epub 2021 Jan 8. PMID: 33411952. Abstract available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/joor.13145

- ↑ Carnero JF, de las Peñas CF, Ge HY, Velasco JP, del Río FG, Santiago RO, Touche RL. Short-Term Effects of Dry Needling of Active Myofascial Trigger Points in the Masseter Muscle in Patients With Temporomandibular Disorders. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2010 Winter;24(1):106-112. PMID: 20213036. Abstract available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20213036/