Lumbar Plexus

Original Editor - Carla Benton

Top Contributors - Carla Benton, Kim Jackson, Admin, Laura Ritchie, Lucinda hampton, Libby McConnell, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop and Carina Therese Magtibay

Description[edit | edit source]

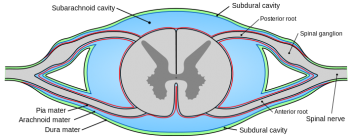

The lumbar spinal nerves are in the intervertebral foramina and are numbered according to the vertebra beneath which they lie. The L1 spinal nerve lies below the L1 vertebrae in the L1-2 intervertebral foramen, L2 lies at the L2-3 intervertebral foramen, and so on. Each spinal nerve is connected to the spinal cord by and dorsal and a ventral root. Peripherally, the spinal nerve divides into a larger ventral rami and smaller dorsal ramus. The spinal nerve roots join the spinal nerve in the intervertebral foramen, and the ventral and dorsal rami are formed just outside the foramen.[1]

The spinal nerves are short, and no longer than the width of the intervertebral foramen in which it lies. The roots of the spinal nerve distribute their fibres directly to the ventral and dorsal rami without really forming a spinal nerve.

The dorsal root of each spinal nerve transmits sensory fibres from the spinal nerve to the spinal cord.[1] The ventral root is largely responsible for transmitting motor fibres from the cord to the spinal nerve, but may transmit some sensory fibres. The spinal cord terminates in the vertebral canal, opposite the level of the L1-2 intervertebral disc, although at times it may end at T12-L1 or as low as L2-3.

File:Interactive spine - intevertebral foramina - L1F8.jpg Intervertebral Foramina, used with permission from Primal Pictures |

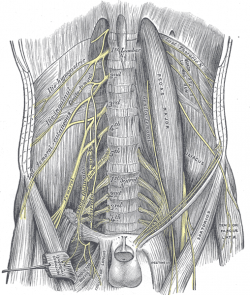

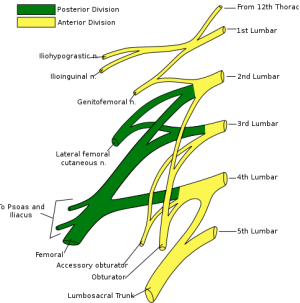

The angle each pair of nerve roots leaves the dural sac varies. L1-2 roots leave the dural sac at an obtuse angle, but the dural sleeves of the lower nerve roots form increasingly acute angles. The angles formed by the L1 and L2 roots are about 80 degrees and 70 degrees, while the angles of the L3 and L4 roots are about 60 degrees.[1] Lumbar 1 through Lumbar 4 donate their anterior rami to creating the lumbar plexus. Sometimes a few fibers from Thoracic 12 are also attached as well. The lumbar plexus innervates the structures of the lower abdomen. The anterior and medial segments of the lower extremity are also innervated. The smaller part of the fourth lumbar nerve joins with the fifth to form the lumbosacral trunk, which forms the sacral plexus. The fourth nerve is named the nervus furcalis, because it is subdivided between the two plexuses.

The branches of the lumbar plexus form the following nerves:

- L1-Iliohypogastric and Ilioinguinal

- L1, L2-Genitofemoral dorsal divisions

- L2, L3-Lateral femoral cutaneous

- L2,L3,L4-Femoral, ventral divisions

- L2, L3, L4-Obturator

- L3, L4-Accessory obturator

The lumbar spine has an extensive innervation system. Posteriorly, branches from the lumbar dorsal rami are distributed to the zygapophysial joints and the back muscles. Anteriorly, the ventral rami supply the quadratus lumborum and psoas major. The vertebral bodies and intervertebral discs are surrounded by plexuses that accompany the longitudinal ligaments and which are derived from the lumbar sympathetic trunks. Within the posterior plexus, larger branches compose the sinuvertebral nerves. Short branches innervate the vertebral periosteum, while long branches enter the vertebral body from all aspects of its circumference. Nerves enter the outer third of the annulus fibrosis from the longitudinal plexuses anteriorly, laterally and posteriorly. The posterior plexus innervates the dura mater and nerve root sleeves. The posterior division also yields the femoral nerve. This is the most important nerve from the lumbar plexus. It innervates the anterior and lateral thigh muscles, as well as medial leg and ending at the foot. The femoral nerve also innervates the quadratus femoris, iliopsoas, and the sartorius muscle with motor coordination. The anterior division of the lumbar plexus yields the obturator nerve. It innervates the cutaneous areas of the medial thigh and the abductor hip musculature.[2]

It is crucial as physical therapists to have a strong knowledge base and understanding of the lumbar plexus in the treatment of our orthopedic patients. In order to accurately determine the cause of our patients' pain or dysfunction, analyzing which level is affected can help us to make better intervention choices, which in turn will create better outcomes.Many times our patients present with only lower extremity deficits, however these often times, are initiated from the lumbar plexus, and not the extremity. Being able to utilize our anatomy and physiology in treating our patients with musculoskeletal dysfunctions can help our patients progress more effectively and quicker, which will help decrease costs of extended treatment due to misdiagnosis. Applying this anatomy with our patients who receive spinal blocks and epidurals can also help us determine the most effective treatment approach and better understand our patient's presentation in the clinic.

| [3] |

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Bogduk, N. Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum. 3rd edition, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. Figure 10-13, page 143; Figure 10.1, page 128.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bogduk, N. Clinical Anatomy of the Lumbar Spine and Sacrum. 3rd edition, Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1997

- ↑ Lumbar nerve plexus Website. Available at http://www.medical-look.com/human_anatomy/organs/Lumbar_nerve_plexus.html/. Accessed November 19, 2009.

- ↑ Anatomy Zone. Lumbar Plexus - Structure and Branches - Anatomy Tutorial. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UmIDCHd0Ai4[last accessed 19/08/15]