Irritable Bowel Syndrome

Original Editors - Mary Page from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Mary Page, James Jolly, Admin, Hannah Wempe, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Elaine Lonnemann, Vidya Acharya, Manisha Shrestha, Dave Pariser and Wendy Walker

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is the most common disorder of the GI system, with symptoms predominantly including diarrhea, constipation, or a combination of both. IBS is considered a functional disorder of motility in the small and large intestine, due to no detectable abnormality of the bowel [1]. IBS can also be referred to as nervous indigestion, functional dyspepsia, spastic colon, irritable colon, pylorospasm, spastic colitis, intestinal neuroses and laxative or cathartic colitis [2].

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

IBS is one of the most commonly diagnosed GI disorders, with a prevalence of 10% to 20% worldwide, and accounting for 50% of sub-specialty referrals in the Western society. [2],[1]. While the prevalence remains high, it is estimated the 25% of Americans experience symptoms of IBS without ever seeking treatment for the disorder [2].

Risk Factors

Many people experience occasional symptoms that can be seen with IBS, however these are some common characteristics of people with the syndrome:[3]

• Young—IBS begins before the age of 35 for 50 percent of people.

• Female—Overall, about twice as many women as men have the condition.

• Family history of IBS—Studies have shown that people who have a first-degree relative — such as a parent or sibling — with IBS are at increased risk of the condition. However, it is unknown whether the risk is related to genes or shared environment.

• Mental health—anxiety, depression, personality disorder, and history of abuse are all associated risk factors

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

GI symptoms associated with IBS are highly variable, normally intermittent and can include but are not limited to the following: [1]

• Painful abdominal cramps

• Constipation

• Diarrhea

• Nausea and vomiting

• Anorexia

• Foul breath

• Sour stomach

• Flatulence

• Abdominal bloating

• White mucus in stool

Pain characteristics include a dull, deep discomfort with sharp cramps in the lower left quadrant of the abdomen. Abdominal pain normally occurs in the morning or after eating and is relieved by evacuation of the bowels[2].

"There is variation and overlap in symptoms for many patients and the variety of symptoms cited are commonly experienced. It is by no means an indication of a typical IBS profile since many patients experience few or all of these symptoms [4]."

"Complications: Diarrhea and constipation, both signs of irritable bowel syndrome, can aggravate hemorrhoids. In addition, if you avoid certain foods, you may not get enough of the nutrients you need, leading to malnourishment.

But the condition's impact on your overall quality of life may be the most significant complication. IBS is likely to limit your ability to:

■ Make or keep plans with friends and family. If you have IBS, the difficulty of coping with symptoms away from home may cause you to avoid social engagements.

■ Enjoy a healthy sex life. The physical discomfort of IBS may make sexual activity unappealing or even painful.

■ Reach your professional potential. People with IBS miss three times as many workdays as do people who don't have the condition.

These effects of IBS may cause you to feel you're not living life to the fullest, leading to discouragement or even depression [4]."

For further information visit this link for a slideshow on IBS: http://www.rxlist.com/irritable_bowel_syndrome_slideshow/article.htm

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Irritable bowel syndrome is often linked to psychological factors including disturbances in circadian rhythm, history of abuse, anxiety, and depression [2][1] It has also been seen with many other pain syndromes and functional disorders such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, tempromandibular joint disorder, chronic pelvic pain, anddysmenorrhea [2][1].

Medications[edit | edit source]

Since people with IBS can have a slower intestinal transit time, resulting in constipation, the use of fiber supplements such as polycarbophil (FiberCon), psyllium seed (Metamucil), and increased intake of water and other fluids is advised. There is also good evidence that antispasmodics and anticholinergics such as dicycomine, hyoscyamine, and peppermint oil are effective in treating symptoms. Furthermore, antidepressants (specifically selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants) have been shown to reduce abdominal pain and other IBS symptoms. Rifaximin, an unabsorbable antibiotic, has also shown marked improvement in the treatment of diarrhea. Lastly, Loperamide can be taken to improve the frequency and consistency of bowel movements, but does not affect other symptoms of the disorder [2].

Aimed at the theory of bacterial overgrowth, continued research on the effectiveness of probiotics on IBS symptoms shows that Bifidobacterium infantis has some efficacy in symptom reduction, however it is still unknown whether other probiotics are as effective.

Medication specifically for IBS

Two medications are currently approved for specific cases of IBS [3]:

- Alosetron (Lotronex): This drug aims to relax the colon and slow movement through the lower bowel. It is intended for cases of IBS that are diarrhea-predominant and that have not responded to other treatments. The drug has only been approved for women and has been linked to rare side effects. Additionally alosetron can only be prescribed by doctors in a special program, as it was removed and now has been reintroduced into the market by the FDA

- Lubiprostone (Amitiza): Lubiprostone is approved for women age 18 and older who have IBS with constipation. It works by increasing fluid secretion in your small intestine to help with the passage of stool. Common side effects include nausea, diarrhea and abdominal pain. Currently, the drug is generally prescribed only for women with IBS and severe constipation for whom other treatments haven't been successful. The drug has not been approved for men and much research is needed on long-term safety of lubiprostone.

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Because there are no physical signs or abnormalities associated with Irritable Bowel Syndrome, there are currently no definitive tests for diagnosis [2][3]. Therefore, diagnosis is usually based on patient history and two sets of symptom-based criteria:

- Rome III criteria—this criteria requires the patient have abdominal pain lasting at least three days a month in the last three months, associated with two or more of the following: [3]

Improved pain with defecation

o Altered frequency of defecation

o Altered consistency of stool

- Manning criteria—this criteria looks at the likelihood of IBS being present based on the following symptoms:[3]

o Pain relieved by defecation

o Incomplete bowel movements

o Mucus in stool

o Changes in stool consistency

In conjunction with the above criteria, patients will need to be screened for any red flag symptoms that could suggest another, more serious condition. These red flags are classified by the Rome III criteria and include:[2]

- New onset of symptoms after age 50

- Short history of symptoms

- Weight loss

- Nocturnal symptoms

- Family history of colon cancer

- Rectal bleeding

- Recent antibiotic use

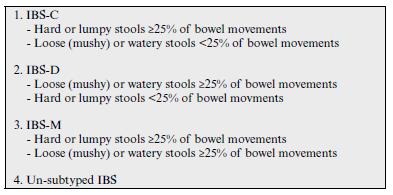

Diagnosis made using the Rome III criteria is usually then classified into four different categories of IBS based on the predominant symptoms (Constipation, Diarrhea, and Mixed), as shown in the figure above. [5]

Diagnosis can also be made by ruling out other diseases or disorders. Diagnosis of exclusion may involve one or more tests such as an ultrasound, thyroid function test, endoscopy (rigid/flexible sigmoidoscopy, colonoscopy, barium enema) to examine the colonic lumen for other possible pathology, complete blood count and stool examination to rule out lactose intolerance and the presence of occult blood, parasites and pathogenic bacteria [3].

Additional tests:

Your doctor may recommend several tests, including stool studies to check for infection or malabsorption problems. Among the tests that you may undergo to rule out other causes for your symptoms are the following:

■Flexible sigmoidoscopy. This test examines the lower part of the colon (sigmoid) with a flexible, lighted tube (sigmoidoscope).

■Colonoscopy. In some cases, your doctor may perform this diagnostic test, in which a small, flexible tube is used to examine the entire length of the colon.

■Computerized tomography (CT) scan. CT scans produce cross-sectional X-ray images of internal organs. CT scans of your abdomen and pelvis may help your doctor rule out other causes of your symptoms.

■Lactose intolerance tests. Lactase is an enzyme you need to digest the sugar found in dairy products. If you don't produce this enzyme, you may have problems similar to those caused by irritable bowel syndrome, including abdominal pain, gas and diarrhea. To find out if this is the cause of your symptoms, your doctor may order a breath test or ask you to exclude milk and milk products from your diet for several weeks.

■Blood tests. Celiac disease (nontropical sprue) is sensitivity to wheat protein that also may cause signs and symptoms like those of irritable bowel syndrome. Blood tests may help rule out that disorder [3]."

"Symptom based (criteria based) approaches can vary widely in their administration and interpretation from one practitioner to the next and have yet to be standardized over any one health profession [6]." Research is still being done to decide the reliability and validity of different symptom based criteria as well as their ability in ruling out other pathology and ruling in IBS as the correct diagnosis.

Causes[edit | edit source]

Since the symptoms of Irritable Bowel Syndrome cannot be attributed to any identifiable abnormality of the bowel, it is thought that IBS may involve various abnormalities of gut function:[2]

- Altered GI motor activity

- Increased intestinal permeability

- Altered intestinal microflora

- Visceral hypersensitivity or hyperalgesia

- Altered processing of information by the nervous system

IBS is characterized by abnormal intestinal contractions theoretically triggered by various causes that differ from person to person. The most common triggers are:

• Foods—the idea of a food allergy or intolerance associated with IBS is not understood, however many people with the syndrome experience symptoms after consuming foods such as chocolate, spices, fats, fruits, beans, cabbage, cauliflower, broccoli, milk, carbonated beverages, and alcohol.

• Stress—most people find that their symptoms are worse during times of extreme stress. Stress is not a cause, however it can aggravate symptoms.

• Hormones—Researchers believe hormones may play a role since women are more likely affected than men. Women also tend to experience symptoms around menstruation.

• Other illnesses—sometimes another illness, such as infection diarrhea or too many bacteria in the intestines, can trigger IBS. [3]

People with IBS have an exaggerated gastrocolic reflex, the signal the stomach sends to the colon to stimulate contractions after food arrives. Some cases IBS have no signs of increased GI motility, suggesting an increased internal sensitivity. This enhanced sensation and perception of what is happening in the digestive tract referred to as “enhanced visceral nociception.” In such cases it may be that the internal pain threshold is lowered for reasons that remain unclear. Individuals with IBS experience pain and bloating at much lower pressures than people without IBS. Serotonin, a neurotransmitter produced in the gut and located inside the enteric nerve cells, may also play a role in the disorder. The GI tract is very sensitive to changes in serotonin levels. It’s possible IBS occurs as a result of abnormalities in serotonin levels responsible for digestive function. Increased levels of serotonin in the gut result in diarrhea, while decreased levels may account for individuals who have IBS-associated constipation.

It is well documented that individuals with IBS report a greater number of symptoms compatible with a history of psychopathologic disorders, abnormal personality traits, psychologic distress, and sexual abuse. Episodes of emotional or psychologic stress, fatigue, smoking, alcohol intake, or eating (expecially a large meal with high fat content, roughage, or fruit) do not cause but rather trigger symptoms. Intolerance of lactose and other sugars may account for IBS in some people.

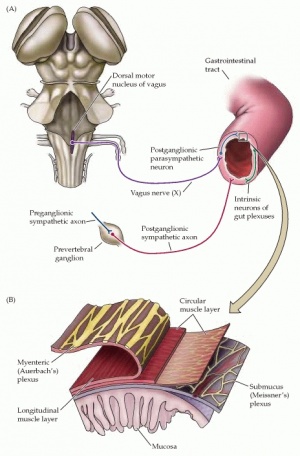

Scientists continue to explore the brain-gut connection to better understand IBS and other functional GI disorders. The enteric nervous system is composed of a vast network of neurons located throughout the GI tract. This neuronal network communicates directly with the brain through the spinal cord. There are as many neurons in the small intestine as in the spinal cord, and the same hormones and chemicals that transmit signals in the brain have been found in the gut, including serotonin, norepinephrine, nitric oxide, and acetylcholine. Studies investigating the effects of emotional words on the digestive tract substantiated the close interaction among mind, brain, and gut. Preliminary data demonstrate an increase in intestinal contractions and change in rectal tone during exposure to angry, sad, or anxious words. These changes of intestinal motor function may influence brain perception [2]"

"Organization of the enteric component of the visceral motor system. (A) Sympathetic and parasympathetic innervation of the enteric nervous system, and the intrinsic neurons of the gut. (B) Detailed organization of nerve cell plexuses in the gut wall. The neurons of the submucus plexus (Meissner's plexus) are concerned with the secretory aspects of gut function, and the myenteric plexus (Auerbach's plexus) with the motor aspects of gut function (e.g., peristalsis) [7]."

"Pyschological factors such as stress, anxiety and depression as well as psychological trauma such as verbal, physical, emotional and sexual abuse have an affect on the intestines by direct connections through the brain gut axis [8]."

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Gastrointestinal System

Small intestine

Large intestine

Neuromuscular System

Enteric Nervous System

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Treatment is aimed at relieving abdominal discomfort, stabilizing bowel habits, and altering underlying causes of the syndrome. Lifestyle changes, especially dietary changes, medications, behavioral counseling, and psychotherapy have been advocated.

**See medication section above for a list of the recommended medications currently used in treatment of IBS.

A stress reduction program with a regular program of relaxation techniques and exercise in conjunction with psychotherapy and biofeedback training may be effective for some people. Behavioral therapy is focused on identifying and reducing or eliminating triggers and reducing negative self-talk. Hypnotherapy can give some control over the muscle activity of the GI tract and the gut’s sensitivity to stress and other influences [2].

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Regular physical activity helps relieve stress and assists in bowel function, particularly in people who experience constipation. The therapist should encourage anyone with IBS to continue with their prescribed rehabilitation intervention program during symptomatic periods.

Therapists must be alert to the person with IBS who has developed breath-holding patterns or hyperventilation in response to stress. Teaching proper breathing is important for all daily activities, especially during exercise and relaxation techniques.

It is also important for therapists—specifically in the field of Women’s Health—to be aware of the correlation between abuse and GI disorders. Therapists can provide these patients with information regarding various resources that victims of abuse may find helpful.

Therapists can also treat the various conditions associated with IBS, such as fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, tempromandibular joint disorder, and chronic pelvic pain, in attempts to decrease symptoms of IBS. The treatment of these conditions can further relieve stress, an associated trigger for IBS symptoms [2].

Dietary Management (current best evidence)

Eliminating foods that trigger symptoms is one of the most effective treatments for IBS. Common suggestions made my doctors include eliminating:

• High-gas foods—foods such as carbonated beverages, cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, and raw fruits can contribute to bothersome bloating or gas.

• Gluten—this is still a controversial topic, however some research shows that diarrhea can be reduced by eliminating gluten from the diet.

• FODMAPs—recent research on IBS has focused on FODMAPs (fermentable oligo-, di-, and monosaccharides and polyols) which are a type of carbohydrate that includes fructose, fructans, lactose, and others. FODMAPs are found in certain grains, vegetables, fruits, and dairy products and people with IBS can benefit from a low FODMAP diet, which may be a trigger for their symptoms. [3]

Herbal tea, such as chamomile (Chamaemelumnobile), can be surprisingly effective due to its relaxation and gentle antispasmodic properties. Peppermint (Mentha piperita) and fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) are both antispasmodics as well as anti-inflammatories. Herbalists often recommend combining these three herbs to make a single dose tea to soothe painful spasms and expel excess wind. Several clinical trials, as well as animal studies, which have shown the potential benefits of peppermint oil in IBS; while further studies illustrate a clear understanding of its mode of action on the gut. However, human studies of peppermint leaf are limited and clinical trials on the actual tea are absent [1].

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

"Inflammatory Bowel Disease:

1) Ulcerative colitis - inflammation and ulceration of the inner lining of the large intestine and rectum.

2) Crohn's disease - inflammatory disease that most commonly attacks the terminal end of the small intestine (ileum) and the colon. However, it can occur anywhere from the mouth to the anus.

Colorectal Cancer:

The presentation of colorectal carcinoma is related to the location of the neoplasm within the colon and the stage of the cancer. Early stage signs and symptoms include rectal bleeding, hemorrhoids, abdominal/back/pelvic/sacral pain, back pain radiating down the legs and changes in bowel patterns. Advanced stage signs and symptoms include constipation progressing to obstruction, diarrhea with copious amounts of mucus, nausea, vomiting, abdominal distention, weight loss, fatigue, dyspnea, and fever [1]."

Case Reports [edit | edit source]

Drossman DA, Ringel Y, Vogt BA, Leserman J, Lin W, Smith JK et al. Alterations of brain activity associated with resolution of emotional distress and pain in a case of severe irritable bowel syndrome. GASTROENTEROLOGY 2003;124:754-761.

Medscape Article: Cash BD. A 32-Year-Old Wman With IBS: Clinical Outcomes and the Use of Antibiotics. Medscape Education Gastroenterology 2011.

Resources[edit | edit source]

World Gastroenterology Organization

Irritable Bowel Syndrome Self Help and Support Group

Irriitable Bowel Syndrome Treatment

International Foundation for Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: About IBS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Goodman, CC, Snyder TE. Differential Diagnosis for phyical therapists: screening for referral. 5th ed St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2013.

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology: implications for the physical therapist. 4th ed. St. Louis: Saunders Elsevier, 2015

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Mayo clinic. Irritable bowel syndrome. http://www.mayoclinic.com/health/irritable-bowel-syndrome/DS00106/DSECTION=prevention (Accessed 29 March 2017).

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Shan Y. Irritable bowel syndrome: diagnosis and management. Primary Health Care 2009;19:28-34.

- ↑ MORAES-FILHO JP, QUIGLEY EMM. THE INTESTINAL MICROBIOTA AND THE ROLE OF PROBIOTICS IN IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME: a review [Internet]. Arquivos de Gastroenterologia. IBEPEGE, CBCD e SBMD, FBG, SBH, SOBED; [cited 2017Apr6]. Available from: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0004-28032015000400331

- ↑ Williams RE, Black CL, Kim HY, Andrews EB, Mangel AW, Buda JJ et al. Stability of irritable bowel syndrome using a roma II-based classification. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2006;23:197-205.

- ↑ NCBI. The enteric nervous system. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bookshelf/br.fcgi?book=neurosci&part=A1398. (Accessed 2 April 2010).

- ↑ IBS research update. The brain gut axis. http://www.ibsresearchupdate.org/ibs/brain1ie4.html. (Accessed 2 April 2010).