Interstitial Cystitis

Original Editors - Sam Gerding from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Sam Gerding, Admin, Kim Jackson, Nicole Hills, Laura Ritchie, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Elaine Lonnemann and Wendy Walker

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Interstitial cystitis is defined by its characteristics due to lack of a standardized diagnostic criteria globally. Both the definition and the diagnosis name have evolved with time.

In 1887, A.J.C. Skene first coined the term interstitial cystitis as meaning "inflammation of the bladder wall" [1]. In 1969, Hanash & Pool, described interstitial cystitis as a condition characterized by urinary symptoms of severely reduced bladder capacity and cystoscopic findings of Hunner’s ulcers[2]. This is also referred to as the "classic interstitial cystitis" due to a finding in 1978 by Messing & Stanley of a "non-ulcer interstitial cystitis".[3] In 1987, the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) introduced a research definition of interstitial cystitis. This definition used inclusion and exclusion factors in describing the syndrome. Many professionals accepted the NIDDK definition as the clinical care definition although the primary purpose was to formulate a basis for research purposes rather than use by clinicians. [1]

In 2002, the International Continence Society proposed an updated definition of interstitial cystitis. While the term interstitial cystitis is reserved for diagnosing patients with characteristic cystoscopic and histologic features of the condition based off the NIDDK criteria another term was developed due to the lack of cytoscopic findings. A new term, Painful bladder syndrome (PBS), was accepted to account for the patients with "typical interstitial cystitis symptoms" but without the cystoscopic finding.[4] Painful bladder syndrome was defined as "suprapubic pain with bladder filling associated with increased daytime and nighttime frequency in the absence of proven urinary infection or other obvious pathology"". The new term is preferred by some clinicians because it defines interstitial cystitis as a syndrome of chronic pain, pressure, or discomfort associated with the bladder, usually accompanied by urinary frequency in the absence of any identifiable cause. The use of the term interstitial cystitis and/or painful bladder syndrome are both commonly used in the United States.

In 2008, the European Society for the Study of Interstitial Cystitis (ESSIC) proposed a new nomenclature and classification system. The proposed name change was to bladder pain syndrome since pain was the fundamental feature of the condition. The definition proposed is "diagnosed on the basis of chronic pelvic pain, pressure, or discomfort perceived to be related to the urinary bladder accompanied by at least one other urinary symptoms like persistent urge to void or urinary frequency"[4].

Finally, an international consensus panel from Europe, Asia, and the United States were sponsored by the Society for Urodynamics and Female Pelvic Health Medicine and Urological Reconstruction to form an international consensus on interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome/painful bladder syndrome to avoid all the confusion.The agreed definition of bladder pain syndrome/interstitial cystitis is an unpleasant sensation (pain, pressure, discomfort) perceived to be related to the urinary bladder, associated with lower urinary tract symptoms of more than 6 weeks’ duration, in the absence of infection or other identifiable causes [5].

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

In the United States, approximately 1 million individuals are affected. The prevalence of interstitial cystitis is higher in the USA than in United Kingdom and Europe [6]

- female:male ratio is approximately 9:1[2]

- rhe average age is between 30-50 [1]

- it appears to be more common in Jewish women [6]

- 90% Caucasian [7]

- low prevalence in the black population [6]

- may occur in pediatric and geriatric populations [1]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Common symptoms [1]

- urinary frequency (includes multiple nighttime voids)

- urinary urgency

- suprapubic pelvic pain related to bladder filling

Associated symptoms

- dyspareunia (pain with intercourse)

- chronic constipation

- slow urinary stream

- food sensitivities that worsen symptoms

- radiating pain in the groin, vagina, rectum, or sacrum [3]

Associated Co-morbidities[1][edit | edit source]

- anxiety

- depression

- migraine

- chronic fatigue syndrome

- dysmennorrhea

- vulvodynia

- fibromyalgia

- irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

- urethral burning

- pelvic floor dysfunction [8]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Most of the oral medications used to treat interstitial cystitis are used in an "off-label" manner without being studied specifically for patients with interstitial cystitis.[2] The only FDA-approved oral medication for interstitial cystitis is Pentosanpolysulfate (Trade name: Elmiron). The drug is designed to enhance the glycosaminoglycan (GAG) layer of the bladder. The theory is that it prevents toxic/inflammatory agents of urine from pentrating the subepithelial layer of the bladder. It is reported that it could take up to 6 months for individuals to receive the desired effect.[9]

Intravesical therapy, where medication is place into the bladder via a catheter rather than being given by mouth or injected into a vein, has been an accepted method of administration for interstitial cystitis. The rationale for intravescial administration is to administer the medication directly to the bladder and elmiate the systemic side effects. Dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) is the only other approved FDA drug for treatment of interstitial cystitis. Although the initial response is high, relapse of symptoms is common.

Other medications used and their purpose with regard to interstitial cystitis:

- Analgesics-<span style="display: none;" /><span style="display: none;" id="1269642211216S" />used to treat moderate pain.

- Corticosteriods- decreasing inflammation and reducing the activity of the immune system.

- Tricyclic antidepressants-used to treat neuropathic pain

- Antihistmines- Inhibits mast cell activation reducing inflammation

- Anticonvulsants- Used to treat the neuropathic pain

- Muscle relaxants- reduce bladder spasms of smooth muscle and allow bladder filling

- Antispasmodics- reduce bladder spasms of smooth muscle and allow bladder filling

- Botulinum Toxin, Type A- a neurotoxin used to reduce local muscle activity

- Anticoagulants- believed to restore the barrier function of the epithelial mucus layer of the urothelium

- Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) Vaccine- suggested that this medication may suppress the inflammatory process of the bladder wall

- Hyaluronic Acid- minimize bladder symptoms and improve quality of life

- Resinifereratoxin- reduce pain by desensitization

The table below provides the level of evidence and the grade of recommendation for the medications used in the medical treatment of interstitial cystitis [3]:

| Type |

Level of Evidence |

Grade of recommendation |

Comments |

| Analgesics |

4 |

C |

Indications limited to cases awaiting further treatment |

| Corticosteroids |

3 |

C |

Not recommended for long-term treatment |

| Hydroxyzine (Antihistamine) |

2b |

B |

Standard Treatment |

| Cimetidine (Antihistamine) |

1b |

A |

Preliminary Data |

| Amitriptyline (Tricyclic Antidepressants) |

1b |

B |

Standard Treatment |

| Sodium Pentosanpolysulfate |

1a |

A |

Standard Treatment |

| Immunosuppressants |

3 |

C |

Insufficient Data & Adverse Reactions |

| Oxybutynin (Antispasmodic) |

3 |

C |

Limited Indication |

| Tolterodine (Antispasmodic) |

3 |

C |

Limited Indication |

| Gabapentin (Anticonvulsant) |

3 |

C |

Preliminary Data |

| Suplatast tosilate (Anti-Allergic) |

3 |

C |

Preliminary Data |

| Nerve Block/ Epidural Pain Pump |

3 |

C |

Crisis Intervention Only |

| Intravesical Treatements |

Level of Evidence |

Grade of Recommendation |

Comments |

| Intravesical Anesthetics |

3 |

C |

|

| Intravesical Pentosanpolysulfate |

1b |

A |

|

| Intravesical Heparin |

3 |

C |

|

| Intravesical Hyauronic Acid |

3 |

C |

|

| Intravesical DMSO |

1b |

A |

|

| Intravesical BCG |

1b |

Not recommended beyond clinical trials |

Contradictory Data |

| Intravesical Clorpactin |

3 |

Not recommended |

Obsolete |

| Intravesical Vanilloids |

1b |

Not recommended beyond clinical trails |

Insufficient Data |

|

Level of Evidence: 1a:Meta-analysis of randomized trials 1b:At least on randomized trial 2a:One well-designed controlled study without randomization 2b: One other type of well-designed quasi-experimental study 3: Non-experimental study (comparative study, correlation study, case reports) 4: Expert committee/opinion. | |||

| Grades of recommendation:

A: Clinical studies of good quality & consistency that include at least 1 randomized trial. B: Well-conducted clinical studies without randomized trials. C: Absence of directly applicable clinical studies of good quality. | |||

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

Diagnostic approaches for interstitial cystitis vary widely. Three consensus panels concluded that the diagnosis is suspected on the basis of history, physical examination, and laboratory tests, including negative urinalysis, negative urine culture, negative cytology, and possibly cystoscopy findings. [10]

Most studies have utilized 3 methods: [2]:[edit | edit source]

- Patient self-reported history

- Physician diagnosis

- Identification of symptoms that suggest interstitial cystitis.

| Method[11] |

Level of Evidence |

Grade of Recommendation | |

|

Patient self-reported history

|

4 |

C | |

|

Physician Diagnosis

|

Examination Procedure |

4 |

C |

|

Optional Recommended Procedures: Cystoscopy, Cystoscopy with hydrodistension, Potassium sensitivity test, & Alkalinized Lidocaine Challenge |

2-3 |

C | |

| Not Recommended Procedures: Bladder Biopsy & Urodynamics | 2-3 | C | |

|

Identifications of symptoms

|

Used for exclusion purpose only. Intended for research use only. | ||

Patient self-reported history questionnaires[11][edit | edit source]

Symptom scores that are theorized to assist with diagnosis, grading the severity, or tracking the response to therapeutic interventions.

O'Leary-Sant Interstitial Cystitis Symptom and Problem Index (O'Leary-Scant score)[edit | edit source]

Consists of 2 symptoms scores the Interstitial Cystitis Symptom Index (ICSI) and Interstitial Cystitis problem Index (ICPI).

Limitation: The ICSI was found to be valid, reliable and responsive measure of change in IC symptoms. However, it underestimated the degree of urgency in interstitial cystitis symptoms. Together the two measures demonstrated a response to change with IC. These should only be used as an adjunct to the diagnosis, not as a screening tool.

Wisconsin Interstitial Cystitis Scale (UW-IC Scale)[edit | edit source]

Includes 7 interstitial cystitis related questions about frequency, urgency, nocturia and pain; these items are mixed in with 18 reference items about other medical problems such as shortness of breath, back pain, and headaches.

Shown to correslate well with the O'Leary-Sant score and demonstrated responsiveness to change over time.

Limitation: Possible ceiling effect for pain that may lower the sensitivity of detecting differences in intervention outcomes.

Pelvic Pain, Urgency, & Frequency (PUF) score[edit | edit source]

Focused attention to urinary urgency/frequency, pelvic pain, and symptoms associated with sexual intercourse.

Able to more efficiently distinguish IC from other urinary tract pathologies.

Limitation: Does not appear to have as extensive validation process as the O'Leary-Scant score or UW-IC Scale.

Take home note[edit | edit source]

All 3 scales distinguished interstitial cystitis but none of the questionnaires had sufficient specificity to serve as the sole diagnostic indicator. All assisted with diagnosis and follow response to therapeutic interventions.[11]

Physician diagnosis[10][edit | edit source]

A physician's diagnosis will be made after an extensive evaluation which includes; the patient's history, frequency volume chart results, a physical examination and an urinalysis

Patient history[edit | edit source]

History of:

- urinary frequency,

- urgency,

- nocturia,

- suprapubic pain

Frequency volume chart[edit | edit source]

A frequency volume chart can be implemented here to differentiate between interstitial cystitis and polyuria.

Physical Examination[edit | edit source]

A complete physical examination should be performed with emphasis related to the abdominal/pelvic exam

- Abdominal region: visual observation should focus on bladder distention, hernias,signs of nerve entrapment, and trigger points abdominally.

- Pelvic region: digital rectal exam and vagina exam differentiate between other possible causes and IC.

- Digital rectal exam: may show rectal or posterior uterine wall masses, nodules, or pelvic floor tenderness.

- Vaginal exam: check for masses, nodules, cervical motion tenderness, point tenderness or lack of mobility in the uterus. Normally pelvic floor muscles are not tender. Women with interstitial cystitis may present with trigger points and taut pelvic floor muscles often have pain in the bladder with palpation. [8]

Urinalysis[edit | edit source]

An urinalysis and urine culture will help rule out if there is a bacterial infection and the presence of an urinary tract infection. Research suggest that there may be two potential urine markers may assist in diagnosis: Antiproliferative factor (APF) and Glycoprotein-51 (GP-51)[1].

Optional Procedures[edit | edit source]

- cystoscopy: test to detect inflammation in the bladder and urethra; Once the bladder is stretched, findings such as a thick, stiff bladder wall; Hunner's ulcers; and glomerulations (pinpoint bleeding) that may be seen.

- cystoscopy with hydrodistension,

- Intravesical Potassium Sensitivity test (Parson's Test) a solution of KCl is left in the bladder for 5 minutes. Provocation of urgency and frequency is rated on a 0-5 scale. A positive test is a MDC of 2. [12]

- alkalinized lidocaine challenge

- bladder biopsy and urodynamics (*not recommended unless specific concerns)

- biopsy of the bladder wall - for a microscopic examination of tissue to rule out bladder cancer and confirm bladder wall inflammation.

| [13] |

Identification of symptoms that suggest interstitial cystitis.[14][edit | edit source]

Initially proposed in 1987, the NIDDK Diagonostic Critera for Interstitial Cystitis became an diagnostic tool since there were limited options at the time of its creation. The sole purpose was for research and it has now been shown to miss an estimated 60% of patients who present with interstitial cystitis.

Automatic Inclusion, positive factors (2 must be present for inclusion):

- Pain on bladder filling relieved by emptying

- Pain (suprapublic, pelvic, urethral, vaginal, or perineal)

- Glomerulations on cystoscopy

Exclusions:

- Nocturia < 2 times per night

- Symptoms duration < 12 months

- Bladder Capacity > 400 mL

- Involuntary bladder contractions

- Other causes of sxs: bladder cancer, cystitis (radiation, tuberculous, bacterial, vaginitis, active herpes, bladder or lower calculi, involuntary bladder contractions.

Causes[edit | edit source]

The etiology and pathogenesis are still not fully understood. Current theories include:

- Infection

- Autoimmunity

- Neurogenic Inflammation

- Epithelial Permability

- Antiproliferative Factor

- Systemic Autoimmune Disorder

- Endocrine Disease

- Genetics

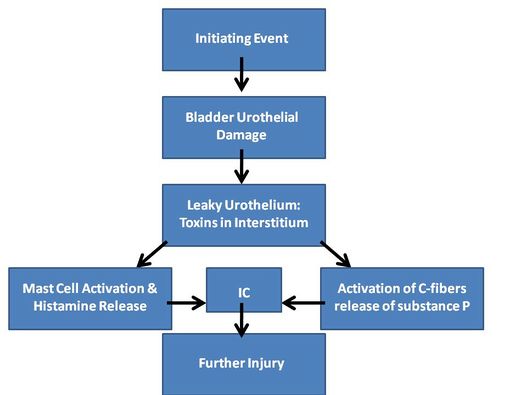

One of the major contentions is that the protective layer of the bladder epithelialium becomes defective. Since this epithelial lining of the protects the bladder from toxins in the urine it is important to understand that once this occurs the toxins are able to penetrate into the interstitial lining of the bladder. The depolarization of the nerve endings occurs which causes severely irritating voiding symptoms and bladder pain.[15]

Classification[edit | edit source]

There are two types of interstitial cystitis yet they differ in when studying their microscopic characteristics, immunity, and physical makeup.

Classic Interstitial Cystitis

- 5-10% of interstitial cystitis patients[16]

- Hunner's ulcers (Red, bleeding areas on the bladder wall during cystoscopy)

- Tends to be found in middle-age to older women

- Decreased bladder capacity noted

- Evidence of inflammation is present which can destroy surrounding tissue.

Non-ulcer Interstitial Cystitis

- Most common type

- 90% of interstitial cystitis patients[16]

- Glomerulations present (pinpoint hemorrhages in the bladder wall)

- Usually affects young to middle-age women

- Normal or increased bladder capacity

- Progression is not evident and evidence of inflammation is not present.

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

A mulitimodal approach is the suggested treatment strategy. It is not common for patients with interstitial cystitis to respond to a single intervention.

The 3 principles of the multimodal approach are[17]:

- Repairing endothelial dysfunction

- Modulation of neural activity

- Stabilization of mast cells

General measures[3]

- Education

- Dietary Modification- avoiding triggers in foodswhich are acidic in nature, high in potassium, contain alcohol, & caffeine

- Bladder Training & Voiding Diary- to assist with extending voiding intervals

Medical management[3]

- Psychotherapy/Sex Therapy

- Pharmacology both oral and intravesical treatments used

- Surgery:

- Nerve Blocks/Epidural pain pumps-crisis intervention only

- Sacral Neuromodulation-not recommended outside clinical trials

- Transurthral resection, coagulation, and LASER- effective with Hunner's ulcers

- Cystectomy-used as a last resort and does not always relieve of pain

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Before initiating manual/structural interventions with a patient, there should be consideration of Red flag symptoms that might suggest the need for referral to eliminate serious pathology.[18]As direct access continues to grow in the United States, there are several key points to consider when examination and evaluation of a patient who presents with interstitial cystitis.

Assessment[edit | edit source]

History[edit | edit source]

- Assist in differential diagnosis between urogenital pain versus musculoskeletal pain

- Assessment of cognitive behavioral aspect of the patient

- Noted food sensitivities and possible triggers

Observation[edit | edit source]

- Overall posture and tone of body

- Correct pelvic and spine alignment noting any malalignments

- Muscular imbalances, flexibility and ROM especially of the hip flexors, internal rotators, adductors. Also checking pectoral and shoulder girdle. A suggestion that a person may be in a posterior pelvic crossed syndrome, ‘‘a posterior (pelvic) shift with increased anterior sagittal rotation or tilt’’. Combining this with an anterior translation of the thorax could lead to poor diaphragmatic control and altered pelvic floor muscle function.[18]

- Breathing pattern and quality; noting excursion of ribs and transverse diaphragm

- Pelvic floor muscle exam

- Bladder pain with interstitial cystitis is felt suprapubically. Bladder pain may also be perceived in the lower back. Hyperesthesia may be present at associated dermatomes (T10-L1).[19]

Key Points[edit | edit source]

- Bladder dysfunction can be confused with neuromusculoskelatal causes of symptoms but seldom relieved with change in position[19].

- Interstitial cystitis presentation has a temporary relief with emptying of bladder.Episodes of waxing and waning of symptoms occurs over time.[7]

- Patients with interstitial cystitis typically have pain in the suprapubic area, however, one study 29% patients reported referral pain in neighboring regions such as the perineal area and abdominal pain.[7]

- In interstitial cystitis patients that have high tone/overacitivity of their pelvic floor muscle (PFM) treatment is warranted[20].

Pelvic Floor Muscles[edit | edit source]

The pelvic floor is composed of several muscles which overlap to form a funnel that holds the pelvic organs in place. Individuals with interstitial cystitis may have a weak pelvic floor due to inactively related to pain or urinary frequency.

There is currently not a standard definition of Pelvic floor muscle strength. The standard strength grading for assessing manual muscle strength in the pelvic floor is the modified Oxford scale. Currently there is not a standard agreement on a system rating for tone of the pelvic floor.

The modified Oxford scale is a 6-point measurement scale:

0 = no response

1= flicker

2 = weak squeeze

3 = moderate squeeze and lift

4 = good squeeze and lift

5 = strong squeeze and lift

EMGs can effectively measure muscle activity however the cost of such equipment limits its use. Digital examination both intra-vaginal and intra-anal are considered the most sensitive in evaluation. Also, manual testing of the muscles will allow the therapist to assess symmetry, balance, and the ability to differentiate which pelvic floor muscles are limited. The muscles which assist in closure are the puborectalis and external ani sphincter. The muscles which assist in lifting are the pubococcygeous and iliococygeus.[20]

Since some patients may not feel comfortable with digital examination, the use of diagnostic ultrasound may be warranted. Real-time ultrasound imaging is a reliable and valid method used by physical therapists to evaluate muscle structure, function, and activation patterns. Studies comparing transabdominal ultrasound measurement and digital palpation testing for PFM evaluationshowed a strong correlation when simultaneously tested. A significant coorelation remains if performed sepearately thus may be a helpful diagnostic tool for pelvic floor muscle dysfunction. Another advantage of this diagnostic tool is the fact that it allows for evaluation of both sides of the pelvic floor at once. [21]

Treatments used by physical therapist after pelvic floor assessment[edit | edit source]

Exercise[edit | edit source]

- Pelvic floor strengthening[20]

- Paradoxical breathing- a paradox occurs when reality conflicts with expectation. During respiration the diaphragm should move caudally on inhalation, however, in paradoxical respiration it moves

cephalad instead.

Modalities[edit | edit source]

- Neuromuscular Re-Ed/Biofeedback-performed well in controlled studies. Showing a decrease in pain and hypertonicity[20].

- Electrical Stimulation:TENS- effective in treating pain pain, High volt galvanic stimulation-reducing spasms[1]

- Ultrasound[20]

- Vaginal dilators[20]

Manual Therapy:[edit | edit source]

- External Pelvic/Intravaginal Myofascial Release- stabilization of hypermobile joints, or enhancement of pelvic floor stability.[18]

- Mobilization of the pelvic floor muscles- stripping, strumming, skin rolling and effleurage[18]

- Joint mobilization[1]

- Muscle energy/PNF- In men, it has been found to be helpful using a "release/hold-relax/contact-relax/reciprocal inhibition technique while voluntarily contracting the voluntarily contract the muscles of the levator endopelvic fascia.[18]

- Strain-Counterstrain[1]

- Intravaginal Thiele massage- a form of internal soft tissue manipulation of pelvic floor muscles developed in the 1930s by a German physician G.H. Thiele. This technique is a deep vaginal massage via a ‘‘back and forth’’ motion over the levator ani, obturator internus, and piriformis muscles. Technique has been effective on high-tone pelvic floor musculature in 90% of patients with interstitial cystitis.[18]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Since there is not a definitive test to identify interstitial cystitis, ruling out other conditions becomes necessary before a diagnosis can be made[19].

Lab tests help rule out:

- Bladder Cancer

- Chronic Prostatisis

- Other forms of cystitis (bacterial, radiation,& tuberculosis)

- Pelvic Inflammatory Diseases (PID)

- Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STDs)

- Vulvovaginitis

- Urinary Tract Infection (UTI)

Imaging may help to rule out:

- Endometriosis

- Nephrolithiasis

- Ureterolithiasis

- Urethral Diverticulum

- Uterine Fibroids

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

- A unique hypnotherapeutic approach to interstitial cystitis: a case report

- Mental Health Diagnoses In Patients with Interstitial Cystitis/ Painful Bladder Syndrome and Chronic Prostatitis/ Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome: A Case/Control Study

- Below the belt: Approach to chronic pelvic pain

Guidelines[edit | edit source]

Cox A, Golda N, Nadeau G, Nickel JC, Carr L, Corcos J, Teichman J. CUA guideline: Diagnosis and treatment of interstitial cystitis/bladder pain syndrome. Canadian Urological Association Journal. 2016 May;10(5-6):E136.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- European Association of Urology

- European Society for the Study of IC/PBS (ESSIC)

- Interstitial Cystitis Network: an online support centre offering patient self-help resources

- International Painful Bladder Foundation (IPBF)

- Interstitial Cystitis Association (ICA)

- National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK)

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?

This presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Irion JM, Irion GL, editors. Women's Health in Physical Therapy. Baltimore (MD): Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2010.p.172-6.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Clemens JQ, Joyce GF, Wise M, Payne CK. Chapter 4. In:Litwin MS, Saigal CS, editors. Urologic Diseases in America. US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Instititue of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 2007; NIH Publication No. 07-5512 p. 125-131

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Fall M, Baranowski AP, Fowler CJ, Lepinard V, Malone-Lee JG, Messelink EJ, et al. EAU guidelines on chronic pelvic pain. Eur Urol 2004; 46:681-89.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 van de Merwe JP, Nordling J, Bouchelouche P, Bouchelouche K, Cervigni M, Daha LK, et al editors. Diagnostic criteria, classification, and nomenclature for painful bladder syndrome/interstitial cystitis: An ESSIC proposal. Eur Urol 2008; 53:60-7

- ↑ UroToday.com [Online]. 2009 Mar 25 [cited 29 Mar 2009]; Available from: URL: http://www.urotoday.com

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Dasgupta J, Tincello DG. Interstitial cysititis/bladder pain syndrome: An update. Maturitas 2009; 64:212-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Teichman JMH, Parsons CL. Contemporary clinical presentation of interstitial cystitis. Urology. 2007;69 (Suppl 4A):41-7.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Peters KM, Carrico DJ, Kalinowski SE, Ibrahim IA, Diokno AC. Prevalence of Pelvic Floor Dysfunction in Patients with Interstitial Cystitis. Urology 2007; 70:16-18.

- ↑ Bordman R, Jackson B. Below the belt: Approach to chronic pelvic pain. Can Fam Physician 2006; 52:1556-1562.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Nickel JC. Interstitial cystitis:etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. Can Fam Physician 2000;46:2430-2440.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Carr LK, Corcos J, Nickel JC, Teichman J. Diagnosis of interstitial cystitis June 2007. Can Urol Assoc J 2009; 3 (1): 81-6.

- ↑ Parson CL, Zupkas P, Parson JK. Intravesical potassium sensitivity in patients with interstitial cystitis and urethral syndrome.Urology 2001 Mar;57(3):428-32;discussion 432-3.

- ↑ DrJosephOnwude. Interstitial Cystitis Cystoscopy interstitialcystitis.org.uk. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NMHtb6dC1o4[last accessed 19/04/14]

- ↑ MacDiarmid SA, Sand PK. Diagnosis of interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome in patients with overactive bladder symptoms. Rev. Urol 2007; 9(1): 9-16.

- ↑ Dell JR. Interstitial cystitis/plainful bladder syndrome:appropriate diagnosis and management. Journal of Women's Health 8 Nov 2007; 16:1181-7.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 International Painful Bladder Foundation. Interstitial cystitis: primary care fact sheet [pamphlet]. International Painful Bladder Foundation.v06102008 0930.

- ↑ Evans RJ.Treatment approaches for interstitial cysitits: Mulitmodality therapy. Rev Urol 2002; 4(suppl 1):S16-S20.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 Chaitow L. Chronic pelvic pain: Pelvic floor problems, sacroiliac dysfunction and the trigger point connection. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies 2007;11,327–339.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Goodman CC, Snyder TEK. Differential diagnosis for physical therapists: screening for referral.4th ed.St. Louis (MO):Saunders Elsevier; 2007. p.671-725.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Rosenbaum TY. Pelvic floor involvement in male and female sexual dysfunction and the role of pelvic rehabilitation in treatment: A literature review. J Sex Med 2007; 4: 4-13.

- ↑ Arab AM, Behabbahani RB, Lorestani L, Afsaneh A.. Correlation of digital palpation and transabdominal ultrasound for assessment of pelvic floor muscle contraction. J Man Manip Ther. 2009; 17(3): e75–e79.