Urinary Incontinence

Original Editor - Kirsten Ryan

Top Contributors - Kirsten Ryan, Nicole Sandhu, Admin, Nicole Hills, Vidya Acharya, Wendy Walker, Kim Jackson, Agoro Bukola Zainab, Merve Demirayak, Temitope Olowoyeye, Laura Ritchie, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Lauren Lopez and Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Urinary is a common condition that often goes under treated. Estimates of prevalence vary depending on the population studied, the measurement period (eg, daily or weekly) and the instruments used to assess severity. It is estimated to affect about 50% of adult women and 3% to 11% in adult men, however, only 25% to 61% of those women seek care.[1][2] This may be due to embarrassment, lack of knowledge about treatment options, or a belief that urinary incontinence is a normal inevitable part of aging.[3]

Definitions[edit | edit source]

Identifying the classification of urinary incontinence can help to guide treatment, however, an individual could exhibit symptoms from more than one of the classifications.[4]

- Urinary incontinence (symptom): Complaint of involuntary loss of urine.

- Stress urinary incontinence: Complaint of involuntary loss of urine on effort or physical exertion (e.g. sporting activities), or on sneezing or coughing.

- Urgency urinary incontinence: Complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency.

- Mixed urinary incontinence: Complaint of involuntary loss of urine associated with urgency and also effort or physical exertion or on sneezing or coughing.

- Urgency: Complaint of a sudden, compelling desire to pass urine which is difficult to defer.

- Overactive bladder (OAB, Urgency) syndrome: Urinary urgency, usually accompanied by frequency and nocturia, with or without urgency urinary incontinence, in the absence of urinary tract infection or other obvious pathology.[5]

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Urinary incontinence remains a worldwide problem, affecting both males and females, across different cultures and races. As mentioned above, the world wide prevalence is difficult to determine due to differences in definitions used, population surveyed, survey type, response rate, age, gender, availability and efficacy of health‐care, and other factors.[6]

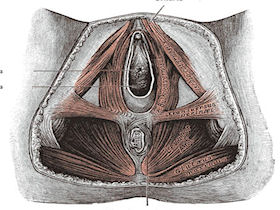

Clinically Relevant Anatomy: Pelvic Floor[edit | edit source]

The pelvic floor is made up of the muscles, ligaments, and fascial structures that act together to support the pelvic organs and to provide compressive forces to the urethra during increased intra-abdominal pressure.

The pelvic floor muscles refer to the muscular layer of the pelvic floor. It includes the levator ani, striated urogenital sphincter, external anal sphincter, ischiocavernosus, and bulbospongiosus.[7]

The urethra, vagina, and rectum pass through the pelvic floor and are surrounded by the pelvic floor muscles. During increased intra-abdominal pressure, the pelvic floor muscles must contract to provide support. When the pelvic floor muscles contract the urethra, anus, and vagina close. The contraction is important in preventing involuntary loss of urine or rectal contents. The pelvic floor muscles must also relax in order to void.[7]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Stress urinary incontinence:

- Urethral hypermobility: increases in intra-abdominal pressure (eg, from coughing or sneezing) with insufficient support of the pelvic floor musculature and vaginal connective tissue to the urethra and bladder neck can lead to incontinence.[9]

- Pregnancy and vaginal birth, post-partum, obesity, chronic cough, chronic heavy lifting and constipation: if there is an increase in abdominal pressure that is greater than the opposing force of the pelvic floor muscles, it can result in stress incontinence[10][11]

- Intrinsic sphincteric deficiency (ISD): this is results from a loss of intrinsic urethral mucosal and muscular tone that normally keeps the urethra closed, it can occur in presence or absence of urethral hypermobility and with minimal abdominal pressure.[12][13]

Urgency urinary incontinence:

- This may be secondary to neurologic disorders (eg, spinal cord injury), bladder abnormalities, increased or altered bladder microbiome, or may be idiopathic.[14][15]

Overactive bladder:

- This could be due to neuropathic, an infection (ie. urinary tract infection), weak pelvic floor muscles, diet (ie. consumption of diuretics), medications, excess weight[16]

Mixed Incontinence:

- Individuals can present with more than one type of incontinence

- For example stress incontinence and/or urge incontinence might be "masked" by an overactive bladder (frequenting the washroom often to avoid leakage).

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

| Risk factors for urinary incontinence (UI) | |

|---|---|

| Age | The prevalence and severity of UI increases with age.[17][18]

Age may not be an independent risk factor, when studies have controlled for co-morbidities.[19] |

| Obesity | This is a strong risk factor for UI. Additionally, weight reduction is associated with improvement or resolution of symptoms, particularly with stress urinary incontinence.[18][20][21] |

| Parity | Increasing parity is a risk factor for UI, however, nulliparous women also report bothersome UI.[22][21] |

| Mode of delivery | Women who have had a vaginal delivery have an increased risk of UI, however, cesarean delivery does not protect women from UI.[23] |

| Family history | This may be a risk factor for UI, particularily with urge incontinence and overactive bladder.[24][25] |

| Other | Conditions such as diabetes, stroke, and depression are associated with an increased risk of UI. [20][26][27] |

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Urine Leaking

- Urinary Frequency

- Urinary Urgency

- Nocturia

- Prolapse

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

A large portion of women with urinary stress incontinence can be diagnosed from clinical history alone. In a systematic review performed in 2006[28], little evidence was found to support the use of urinary diaries, and pad-tests although these measures are common diagnostic assessments used in physical therapy.[28]

Clinical history[edit | edit source]

Clinical history taking compared with multi-channel urodynamics was found to have 0.92 sensitivity and 0.56 specificity for the diagnosis of urinary stress incontinence based on the presence of stress incontinence symptoms.[28]

Pelvic Floor Muscle Function and Strength[edit | edit source]

Modified Oxford grading system:

- 0 - no contraction

- 1 - flicker

- 2 - weak squeeze, no lift

- 3 - fair squeeze, definite lift

- 4 - good squeeze with lift

- 5 - strong squeeze with a lift

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Palpation of the pelvic floor muscles per the vagina in females and per the rectum in male patients.[29]

PERFECT mnemonic assessment[29]:

P - power, may use the Modified Oxford grading scale

E - endurance, the time (in seconds) that a maximum contraction can be sustained

R - repetition, the number of repetitions of a maximum voluntary contraction

F - fast contractions, the number of fast (one second) maximum contractions

ECT - every contraction timed, reminds the therapist to continually overload the muscle activity for strengthening[29]

Pad Test[edit | edit source]

The 1 hour pad test was found to have 0.94 sensitivity and 0.44 specificity for diagnosing any leakage compared with multi-channel urodynamics.

The 48 hour pad-test was found to have 0.92 sensitivity and 0.72 specificity for the diagnosis of urinary stress incontinence.[28]

Urinary (Voiding) Diary[edit | edit source]

One study found a scale derived from a 7 day diary was 0.88 sensitive and 0.83 specific for the diagnosis of detrusor overactivity in women.[28] The National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases provides clinicians with a easy to use Bladder Diary pdf that may be used in clinical practice[30].

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

- Incontinence Quality of Life Instrument (I-QOL)

- International Consultation on Incontinence Modular Questionnaires (ICIQ)

- Male Urogenital Distress Inventory (MUDI)

- Male Urinary Symptom Impact Questionnaire (MUSIQ)

- Patient Global Impression of Improvement (PGI-I)

- Patient Global Impression of Severity (PGI-S)

- Pelvic Floor Distress Inventory - 20 (PFDI - 20)

- Pelvic Floor Impact Questionnaire - 7 (PFIQ - 7)

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Pelvic Floor Muscle Training (PFMT)[edit | edit source]

The pelvic floor muscles are known as the levator ani, made up of the pubococcygeus - puborectalis complex. Those muscles form a sling around the anorectal junction. They are made up of both Type I (slow-twitch) and Type II (fast-twitch) fibers. The majority are Type I (about 70%) which provide sustained support and are fatigue resistant. The remaining Type II fibers provide the quick compressive forces necessary to oppose leakage during increased abdominal pressure. A contraction of the pelvic floor muscles also causes a reflex inhibition of the detrusor muscle.[31]

Patient specific training is necessary to ensure a proper contraction of the pelvic floor muscle group. It is also essential to train both the fast and slow-twitch muscle fibers. Also, training must include instruction in volitional contractions before and during an activity that may cause incontinence, such as coughing, sneezing, and lifting.[29] Patients are typically recommended to perform the exercises four to five times daily.[32][29]

PFMT for the prevention of postpartum incontinence[edit | edit source]

Pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) performed during pregnancy help to decrease the short-term risk of urinary incontinence in women without prior incontinence. A meta-analysis that included randomised or quasi-randomised trials on pregnant or postnatal women, found that women assigned to antenatal PFMT had a significant decrease in the rate of urinary incontinence at up to three months postpartum.[33]

A systematic review including randomised or quasi-randomised trials on primiparous or multiparous pregnant or postpartum women found that PFMT during pregnancy and after delivery can prevent and treat urinary incontinence. The authors recommended a supervised training protocol following strength-training principles, emphasizing close to maximum contractions and lasting at least 8 weeks.[34]

PFMT for stress urinary incontinence[edit | edit source]

Similarly to the findings stated above, PFMT has been found to be effective for treating stress urinary incontinence as well.[35][36] A systematic review looking at the effects of PFMT by comparing the effects of this training with no treatment, or with any inactive treatment (for example, advice on management with pads). The authors found women with stress urinary incontinence in the PFMT group were, on average, eight times more likely to report being cured. In addition the participants reported an improved QoL.[36]

A study examining the training parameter for strengthening the pelvic floor found the most effective protocol to consists of digital palpation combined with biofeedback monitoring and vaginal cones, including 12 week training parameters, and ten repetitions per series in different positions.[35]

PFMT for urgency incontinence[edit | edit source]

PFMT has been shown to improve or cure symptoms of urge urinary incontinence.[36] In addition to PFMT, behavioural therapies and bladder training (described below) may be beneficial in this population.[37][38]

Behavioral Therapy[edit | edit source]

The focus of behavioral therapy is on lifestyle changes such as fluid or diet management, weight control, and bowel regulation. Education about bladder irritants, like caffeine, is an important consideration. Also, discussing bowel habits to determine if constipation is an issue as it is important to educate the patient about avoiding straining.[37] Education and explanation about normal lower urinary tract function is also included. Patients should understand the role of the bladder and the pelvic floor muscles.[39] A randomized clinical trial examined the effects of a group-administered behavioural therapy for urinary incontinence in older women and found it to be a modestly effective treatment for reducing symptoms of urinary incontinence. The group behavioural therapy included a one-time, two hour bladder health class, including written material and an audio CD.[40]

Bladder Training[edit | edit source]

The information gathered from the bladder diary is used to guide decision making for bladder re-training, including a voiding schedule if necessary to increase the capacity of the bladder for people with frequency issues. Bladder training attempts to break the cycle by teaching patients to void on a schedule, rather than in response to urgency. Urge suppression techniques are taught, such as distraction and relaxation. It is also important to teach the patient to contract the pelvic floor to cause detrusor inhibition. A voluntary contraction of the pelvic floor muscles helps increase pressure in the urethra, inhibit detrusor contractions, and control urinary leakage.[37] [39]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Multi-channel urodynamics testing is the gold standard for making a condition-specific diagnosis. This testing is typically done in secondary care, not in primary care or physical therapy.[28]

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

A systematic review published in the Annals of Internal Medicine in 2008[41] found good evidence that pelvic floor muscle training and bladder training resolved urinary incontinence in women. However, the effects of electrostimulation, medical devices, injectable bulking agents, and local estrogen therapy were inconsistent.[41]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Physiopedia's Clinical Guidelines: Pelvic Health Page

Websites[edit | edit source]

- American Urogynecologic Society (AUGS) at www.augs.org

- American Urological Association (AUA) at www.auanet.org

- International Continence Society (ICS) at www.icsoffice.org

- National Association for Continence (NAFC) at www.nafc.org

- National Institute on Aging at www.nia.nih.gov

- National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases at https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/bladder-control-problems/diagnosis

- Section on Women's Health, APTA at www.women'shealthapta.org

- The Simon Foundation for Continence at www.simonfoundation.org

- Chartered Society of Physiotherapy: Physiotherapy Works! for urinary incontinence

Presentations[edit | edit source]

|

Pelvic Physiotherapy - to Kegel or Not?

This presentation was created by Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction. She also provides education and mentorship to physiotherapists who are similarly interested in treating these dysfunctions. In the presentation, Carolyn reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients. |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Minassian VA, Yan X, Lichtenfeld MJ, Sun H, Stewart WF. The iceberg of health care utilization in women with urinary incontinence. International urogynecology journal. 2012 Aug 1;23(8):1087-93.

- ↑ Hannestad YS, Rortveit G, Hunskaar S. Help-seeking and associated factors in female urinary incontinence. The Norwegian EPINCONT Study. Scandinavian journal of primary health care. 2002 Jan 1;20(2):102-7.

- ↑ University of Michigan. National poll on healthy aging. Available from: https://www.healthyagingpoll.org/sites/default/files/2018-11/NPHA_Incontinence-Report_FINAL-110118.pdf

- ↑ Barry MJ, Link CL, McNaughton‐Collins MF, McKinlay JB, Boston Area Community Health (BACH) Investigators. Overlap of different urological symptom complexes in a racially and ethnically diverse, community‐based population of men and women. BJU international. 2008 Jan;101(1):45-51.

- ↑ Abrams P, Cardozo L, Fall M, et al. The standardization of terminology in lower urinary tract function: report from the standardization sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Urology 2003;61:37-49.

- ↑ Minassian VA, Drutz HP, Al‐Badr A. Urinary incontinence as a worldwide problem. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2003 Sep;82(3):327-38.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Messelink B, Benson T, Berghmans B, Bo K, Corcos J, Fowler C, Laycck J, Huat-Chye Lim P, van Lunsen R, Lycklama a Nijeholt G, Pemberton J, Wang A, Watier A, Van Kerrebrocck P. Standardization of terminology of pelvic floor muscle function and dysfunction: report from the pelvic floor clinical assessment group of the International Continence Society. Neurourol Urodyn 2005;24:374-380.

- ↑ Natural Childbirth. Childbirth and your pelvic floor. http://childbirth.amuchbetterway.com/childbirth-and-your-pelvic-floor/ (accessed 15 March 2011).

- ↑ Pirpiris A, Shek KL, Dietz HP. Urethral mobility and urinary incontinence. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2010 Oct;36(4):507-11.

- ↑ International Urogynecological Association. Stress urinary incontinence. Available from: https://www.yourpelvicfloor.org/media/Stress_Urinary_Incontinence_RV1.pdf

- ↑ McGuire EJ. Pathophysiology of stress urinary incontinence. Reviews in urology. 2004;6(Suppl 5):S11.

- ↑ Lim YN, Dwyer PL. Effectiveness of midurethral slings in intrinsic sphincteric-related stress urinary incontinence. Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2009 Oct 1;21(5):428-33.

- ↑ Pizzoferrato AC, Fauconnier A, Fritel X, Bader G, Dompeyre P. Urethral closure pressure at stress: A predictive measure for the diagnosis and severity of urinary incontinence in women. International neurourology journal. 2017 Jun;21(2):121.

- ↑ Schneeweiss J, Koch M, Umek W. The human urinary microbiome and how it relates to urogynecology. International urogynecology journal. 2016 Sep 1;27(9):1307-12.

- ↑ Pearce MM, Zilliox MJ, Rosenfeld AB, Thomas-White KJ, Richter HE, Nager CW, Visco AG, Nygaard IE, Barber MD, Schaffer J, Moalli P. The female urinary microbiome in urgency urinary incontinence. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2015 Sep 1;213(3):347-e1.

- ↑ Steers WD. Pathophysiology of overactive bladder and urge urinary incontinence. Reviews in urology. 2002;4(Suppl 4):S7.

- ↑ Wu JM, Vaughan CP, Goode PS, Redden DT, Burgio KL, Richter HE, Markland AD. Prevalence and trends of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2014 Jan;123(1):141.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Nygaard I, Barber MD, Burgio KL, Kenton K, Meikle S, Schaffer J, Spino C, Whitehead WE, Wu J, Brody DJ, Pelvic Floor Disorders Network. Prevalence of symptomatic pelvic floor disorders in US women. Jama. 2008 Sep 17;300(11):1311-6.

- ↑ Lawrence JM, Lukacz ES, Nager CW, Hsu JW, Luber KM. Prevalence and co-occurrence of pelvic floor disorders in community-dwelling women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2008 Mar 1;111(3):678-85.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Lawrence JM, Lukacz ES, Liu IL, Nager CW, Luber KM. Pelvic floor disorders, diabetes, and obesity in women: findings from the Kaiser Permanente Continence Associated Risk Epidemiology Study. Diabetes Care. 2007 Oct 1;30(10):2536-3541.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Othman JA, Åkervall S, Milsom I, Gyhagen M. Urinary incontinence in nulliparous women aged 25-64 years: a national survey. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2017 Feb 1;216(2):149-e1.

- ↑ Lukacz ES, Lawrence JM, Contreras R, Nager CW, Luber KM. Parity, mode of delivery, and pelvic floor disorders. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2006 Jun 1;107(6):1253-60.

- ↑ Hutton EK, Hannah ME, Willan AR, Ross S, Allen AC, Armson BA, Gafni A, Joseph KS, Mangoff K, Ohlsson A, Sanchez JJ. Urinary stress incontinence and other maternal outcomes 2 years after caesarean or vaginal birth for twin pregnancy: a multicentre randomised trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 2018 Dec;125(13):1682-90.

- ↑ Hannestad YS, Lie RT, Rortveit G, Hunskaar S. Familial risk of urinary incontinence in women: population based cross sectional study. Bmj. 2004 Oct 14;329(7471):889-91.

- ↑ Wennberg AL, Altman D, Lundholm C, Klint Å, Iliadou A, Peeker R, Fall M, Pedersen NL, Milsom I. Genetic influences are important for most but not all lower urinary tract symptoms: a population-based survey in a cohort of adult Swedish twins. European urology. 2011 Jun 1;59(6):1032-8.

- ↑ Phelan S, Grodstein F, Brown JS. Clinical research in diabetes and urinary incontinence: what we know and need to know. The Journal of urology. 2009 Dec 1;182(6):S14-7.

- ↑ Matthews CA, Whitehead WE, Townsend MK, Grodstein F. Risk factors for urinary, fecal or dual incontinence in the Nurses’ Health Study. Obstetrics and gynecology. 2013 Sep;122(3):539.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 28.4 28.5 Martin JL, Williams KS, Sutton AJ, Abrams KR, Assassa RP. Systematic review and meta-analysis of methods of diagnostic assessment for urinary incontinence. Neurourol Dynam 2006;25:674-683.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 29.3 29.4 Laycock J. Pelvic muscle exercises: physiotherapy for the pelvic floor. Urologic Nursing 1994;14:136-40.

- ↑ The National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Bladder Diary. Available from: https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/bladder-control-problems/diagnosis. [last accessed 17/8/2018]

- ↑ Doughty DB. Promoting continence: simple strategies with major impact. Ostomy Wound Management 2003;49:46-52.

- ↑ Alewijnse D, Metsemakers JFM, Mesters I, van den Borne. Effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle exercise therapy supplemented with a health education program to promote long-term adherence among women with urinary incontinence. Neurology and Urodynamics 2003;22:284-295.

- ↑ Woodley SJ, Boyle R, Cody JD, Mørkved S, Hay‐Smith EJ. Pelvic floor muscle training for prevention and treatment of urinary and faecal incontinence in antenatal and postnatal women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2017(12).

- ↑ Mørkved S, Bø K. Effect of pelvic floor muscle training during pregnancy and after childbirth on prevention and treatment of urinary incontinence: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med. 2014 Feb 1;48(4):299-310.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Oliveira M, Ferreira M, Azevedo MJ, Firmino-Machado J, Santos PC. Pelvic floor muscle training protocol for stress urinary incontinence in women: A systematic review. Revista da Associação Médica Brasileira. 2017 Jul;63(7):642-50.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Dumoulin C, Cacciari LP, Hay‐Smith EJ. Pelvic floor muscle training versus no treatment, or inactive control treatments, for urinary incontinence in women. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2018(10).

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 Burgio KL. Current perspectives on management of urgency using bladder and behavioral training. J Am Academy Nurse Pract 2004;16:4-7.

- ↑ The Canadian Continence Foundation. Treating incontinence. Available from: http://www.canadiancontinence.ca/EN/treatment.php

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Payne CK. Behavioral therapy for overactive bladder. Urology 2000;55:3-6.

- ↑ Diokno AC, Newman DK, Low LK, Griebling TL, Maddens ME, Goode PS, Raghunathan TE, Subak LL, Sampselle CM, Boura JA, Robinson AE. Effect of Group-Administered Behavioral Treatment on Urinary Incontinence in Older Women: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA internal medicine. 2018 Oct 1;178(10):1333-41.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Shamliyan TA, Kane RL, Wyman J, Wilt TJ. Systematic review: randomized, controlled trials of nonsurgical treatments for urinary incontinence in women. Ann Intern Med 2008;148:459-474.