Hypertension

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Nupur Smit Shah, Rishika Babburu and Areeba Raja

Introduction[edit | edit source]

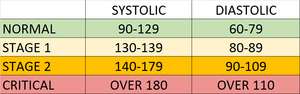

The current definition of hypertension (HTN) is systolic blood pressure (SBP) values of 130mmHg or more and/or diastolic blood pressure (DBP) more than 80 mmHg. Persistent BP readings of 140/90mmHg or more should undergo treatment with the usual therapeutic target of 130/80mmHg or less.[1]

Salient Facts

- Hypertension - or elevated blood pressure - is a serious medical condition that significantly increases the risks of heart, brain, kidney and other diseases.

- An estimated 1.13 billion people worldwide have hypertension, most (two-thirds) living in low- and middle-income countries.

- In 2015, 1 in 4 men and 1 in 5 women had hypertension.

- Fewer than 1 in 5 people with hypertension have the problem under control.

- Hypertension is a major cause of premature death worldwide and ranks among the most common chronic medical condition.[1]

- One of the global targets for noncommunicable diseases is to reduce the prevalence of hypertension by 25% by 2025 (baseline 2010)[2].

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Most cases of hypertension are idiopathic which is also known as essential hypertension.

- It has long been suggested that an increase in salt intake increases the risk of developing hypertension.

- One of the described factors for the development of essential hypertension is the patient genetic ability to salt response. About 50 to 60% of the patients are salt sensitive and therefore tend to develop hypertension[1]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Modifiable risk factors include unhealthy diets (excessive salt consumption, a diet high in saturated fat and trans fats, low intake of fruits and vegetables), physical inactivity, consumption of tobacco and alcohol, and being overweight or obese.

Non-modifiable risk factors include a family history of hypertension, age over 65 years and co-existing diseases such as diabetes or kidney disease[2].

Signs and Symptoms[edit | edit source]

Hypertension is called a "silent killer". Most people with hypertension are unaware of the problem because it may have no warning signs or symptoms.

- When symptoms do occur they include: early morning headaches; nosebleeds; irregular heart rhythms; vision changes; buzzing in the ears.

- Severe hypertension can cause: fatigue; nausea; vomiting; confusion; anxiety; chest pain; muscle tremors.

- An evaluation of BP by a health professional is important for assessment of risk and associated conditions[2].

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

- More than one billion adults worldwide have hypertension with up to 45% of the adult populace being affected with the disease.

- The high prevalence of hypertension is consistent across all socio-economic and income strata, and the prevalence rises with age accounting for up to 60% of the population above 60 years of age.

- In the year 2010, the global health survey report (which comprised of patient data from 67 countries), reported Hypertension as the leading cause of death and disability-adjusted life years worldwide since the year 1990.

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

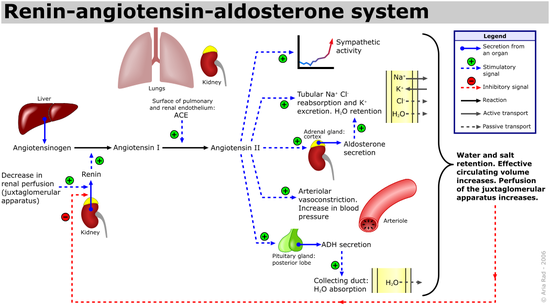

There are various mechanisms described for the development of hypertension which includes:

- Increased salt absorption resulting in volume expansion,

- An impaired response of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS),

- Increased activation of the sympathetic nervous system.

These changes lead to the development of increased total peripheral resistance and increased afterload which in turn leads to the development of hypertension[1].

Measurement and Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Blood pressure is measured using a machine called a sphygmomanometer.

- Manual sphygmomanometers employ a small handheld air pump inflates the cuff. A machine inflates the cuff for an automated sphygmomanometer. Once it’s fully inflated, an air valve slowly releases the pressure in the cuff (the patient should remain seated quietly for at least 5 minutes before taking the blood pressure). The blood pressure cuff should cover 80% of the arm circumference because larger or smaller pressure cuffs can falsely under-estimate or over-estimate blood pressure readings.

- A reading with two numbers is created, written down with one number on top of the other e.g. 120/80 mm Hg. The top number is systolic blood pressure (i.e. the amount of pressure in your arteries when your heart muscle contracts). The bottom number is diastolic blood pressure (i.e. your blood pressure when your heart muscle is between beats)[3].

Non Pharmacological management[edit | edit source]

Non-pharmacological and lifestyle management are recommended for all individuals with raised BPs regardless of age, gender, comorbidities or cardiovascular risk status.

- Patient education is paramount to effective management and should always include detailed instructions regarding weight management, salt restriction, smoking management, adequate management of obstructive sleep apnea and exercise.

- Reducing and managing mental stress

- Regularly checking blood pressure

- Managing other medical conditions[1][2]

Pharmacological Management of Hypertension[edit | edit source]

Pharmacological therapy consists of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEi), angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), diuretics (usually thiazides), calcium channel blockers (CCBs) and beta-blockers (BBs), which are instituted taking into account age, race and comorbidities such as presence of renal dysfunction, LV dysfunction, heart failure and cerebrovascular disease. See link above.

Complications[edit | edit source]

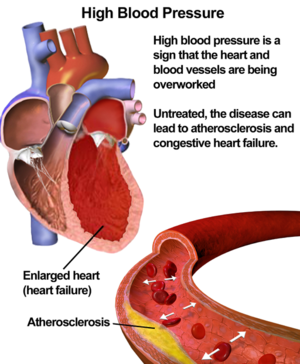

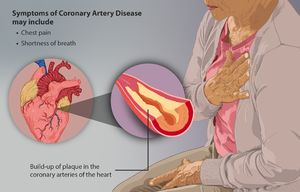

There is a clear link between high blood pressure and an increased risk of heart disease, in particular having a heart attack or stroke.

- Myocardial infarction (MI): Long-standing high blood pressure leads to left ventricular hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction that cause an increase in myocardial rigidity, which renders the myocardium less compliant to changes in the preload, afterload, and sympathetic tone. Adequate blood pressure control must be achieved in patients with hypertension to prevent progression to overt heart failure[4].

Complications also include:

- Coronary Artery disease (CAD)

- Hypertensive encephalopathy

- Renal failure, acute versus chronic

- Peripheral arterial disease

- Atrial fibrillation

- Aortic aneurysm

- Death (usually due to coronary heart disease, vascular disease, stroke-related)

Resistant Hypertension (RHTN) and Refractory Hypertension[edit | edit source]

1.RHTN

Defined as uncontrolled blood pressure despite the use of ≥3 antihypertensive agents of different classes, including a diuretic, a long-acting calcium channel blocker, and a blocker of the renin- angiotensin system, at maximal or maximally tolerated doses.

- Antihypertensive medication nonadherence and the white coat effect must be excluded to make the diagnosis.

- RHTN is a high-risk phenotype, leading to increased all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease outcomes.

- Healthy lifestyle habits are associated with reduced cardiovascular risk in patients with RHTN.

- Aldosterone excess is common in patients with RHTN, and addition of spironolactone or amiloride to the standard 3-drug antihypertensive regimen is effective at getting the blood pressure to goal in most of these patients.

2. Refractory hypertension

Defined as uncontrolled blood pressure despite use of ≥5 antihypertensive agents of different classes, including a long-acting thiazide-like diuretic and an MR (mineralocorticoid receptor) antagonist, at maximal or maximally tolerated doses. Fluid retention, mediated largely by aldosterone excess, is the predominant mechanism underlying RHTN, while patients with refractory hypertension typically exhibit increased sympathetic nervous system activity.[5]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Secondary hypertension should always be sought for as the differential especially if the patient is at extremes of age (young or elderly).

- Hyperaldosteronism, coarctation of the aorta, renal artery stenosis, chronic kidney disease, and aortic valve disease should always be kept in the differential.[1]

Patient Education Recommendations[edit | edit source]

Physical therapists should contribute to educating patients to monitor and manage their blood pressure, as early as childhood, before it becomes a serious health problem. The incidence of pediatric hypertension is increasing as a result of the obesity epidemic. Diet and exercise implemented at a young age is crucial in the prevention of hypertension.[6] When medications are implicated, adherence is crucial in long-term management. It has been shown that approximately 50% of patients don’t take medications as prescribed.[7] According to the WHO, “lack of adherence is the most important cause of failure to achieve BP control”.[10] While medication adherence is important, physical activity should be equally emphasized, especially because it’s a primary prevention technique. Aerobic exercise is universally implemented for hypertensive treatment because it lowers BP 5-7 mmHg among adults. Thirty minutes or more per day of moderate-intensity exercise combined with resistance exercise 2-3 days per week is recommended.[8]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Iqbal AM, Jamal SF. Essential Hypertension. InStatPearls [Internet] 2019 Dec 1. StatPearls Publishing.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539859/?report=reader (last accessed 11.12.2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 WHO Hypertension Available from:https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hypertension (last accessed 11.12.2020)

- ↑ Heart Foundation Blood Pressure Available from:https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/heart-health-education/blood-pressure-and-your-heart (last accessed 12.12.2020)

- ↑ Oh GC, Cho HJ. Blood pressure and heart failure. Clinical Hypertension. 2020 Dec 1;26(1):1.Available from:https://clinicalhypertension.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s40885-019-0132-x (last accessed 12.12.2020)

- ↑ Acelajado MC, Hughes ZH, Oparil S, Calhoun DA. Treatment of resistant and refractory hypertension. Circulation research. 2019 Mar 29;124(7):1061-70.Available from:https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312156 (accessed 12.12.2020)

- ↑ Misurac, J, Nichols, KR, Wilson, AC. Pharmacologic management of pediatric hypertension. Pediatric Drugs. February, 2016; 18(1), 31-43. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s40272-015-0151-3. Accessed November 29, 2018.

- ↑ Brown, MT, Bussell, JK. Medication Adherence: WHO Cares? Mayo Clinic Proceedings. April, 2011; 86(4), 304–314. http://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0575. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21389250/ Accesed November 12.12.2020

- ↑ Pescatello, LS, MacDonald, HV, Lamberti, L, Johnson, BT. Exercise for Hypertension: A Prescription Update Integrating Existing Recommendations with Emerging Research. Current Hypertension Reports. November, 2015; 17(11), 87.Available from:https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11906-015-0600-y (last accessed 12.12.2020)