Hypernatremia

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton and Kim Jackson

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Hypernatremia is defined as a serum sodium level over 145 mM. The normal concentration of sodium in the blood plasma is 136-145 mM. Severe hypernatremia, with serum sodium above 152 mM, can result in seizures and death.

- Sodium is a dominant cation in extracellular fluid and necessary for the maintenance of intravascular volume. The human body maintains sodium and water homeostasis by concentrating the urine secondary to the action of antidiuretic hormone (ADH) and increased fluid intake by a powerful thirst response. These mechanisms protect us from developing hypernatremia and are impaired in: certain vulnerable populations; ADH deficiency; unresponsiveness at the renal tubular level.[1]

- Manifestations include confusion, neuromuscular excitability, hyperreflexia, seizures, and coma.

- Hypernatremia is very common in the ICU. It often develops during ICU admission due to inadequate free water administration (particularly among intubated patients which may be inappropriately treated with sedatives or antipsychotics)[2].

- Hypernatremia may cause delirium, thereby increasing the length of ventilation and ICU stay.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Hypernatremia is primarily seen in infants and the elderly population.

- Infants receiving inadequate water replacement in the setting of gastroenteritis or ineffective breastfeeding are common scenarios.

- Community-acquired hypernatremia generally occurs in elderly people who are mentally and physically impaired, often with an acute infection[3].

- Premature infants are at higher risk due to their relatively small mass to surface area and their dependency on the caretaker to administer fluids.

- Patients with neurologic impairment also are at risk due to impaired thirst mechanism and lack of water availability.

- Hypernatremia can occur in the hospital setting due to hypertonic fluid infusions, especially when combined with the patient's inability for adequate water intake[1]

- Hypernatremia is very common in the ICU.[2]

Etiology[edit | edit source]

Water deficit

Common:

- Gastrointestinal loss eg diarrhoea, stomal losses

- Skin loss (excess sweating/burns)

- Renal losses eg intrinsic renal disease, post-obstructive diuresis, and with the use of osmotic or loop diuretics.

- Hyperglycemia and mannitol are common causes of osmotic diuresis[1].

- Inability to obtain water, including breastfed babies due to inadequate milk supply

Less Common:

- Diabetes insipidus (central, nephrogenic, systemic disease, drugs)

- Increased insensible losses

- Impaired thirst mechanism secondary to underlying neurological abnormalities or hypothalamic dysfunction

Sodium Excess

- Ingestion of high sodium (inappropriate formula concentration, high osmolality rehydration solutions, salt poisoning)

- Iatrogenic (hypertonic saline, sodium bicarbonate)

Hyperaldosteronism

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Most patients present with symptoms suggestive of fluid loss and clinical signs of dehydration.

- Symptoms and signs of hypernatremia are secondary from central nervous system dysfunction and are seen when serum sodium rises rapidly or is greater than 160 meq/L.

- Infants and Children present with irritability and agitation, which can progress to lethargy, somnolence, and coma.

- Other symptoms include increased thirst response in alert patients and high-pitched cry in infants.

- Patients with diabetes insipidus present with polyuria and polydipsia.

- The skin can feel doughy or velvety due to intracellular water loss.

- Orthostatic hypotension and tachycardia are usually present in hypovolemic hypernatremia.

- The patient may have increased tone with brisk reflexes and myoclonus.[1]

An interesting note on maximal sport exertion

- A short burst of intensive exercise (100-m swim lasting one minute and resulting in a 12-fold rise in the level of blood lactate) resulted in frank hypernatremia (serum sodium level, >150 mEq/L) in 30% to 40% of well-trained athletes. In contrast, less intensive exercise (800-m swim lasting ten minutes and resulting in a sevenfold rise in the level of blood lactate) failed to cause a rise in serum sodium level despite comparable elevations in hematocrit reading and serum protein levels.

- Hypernatremia induced by intensive exercise cannot be explained by losses in body fluid or solute ingestion, but is probably a consequence of a shift of hypotonic fluid from the extracellular to the intracellular compartment. Thus, the mechanism of exercise-induced hypernatremia may be unique, as compared with other clinically recognized forms of hypernatremia[5].

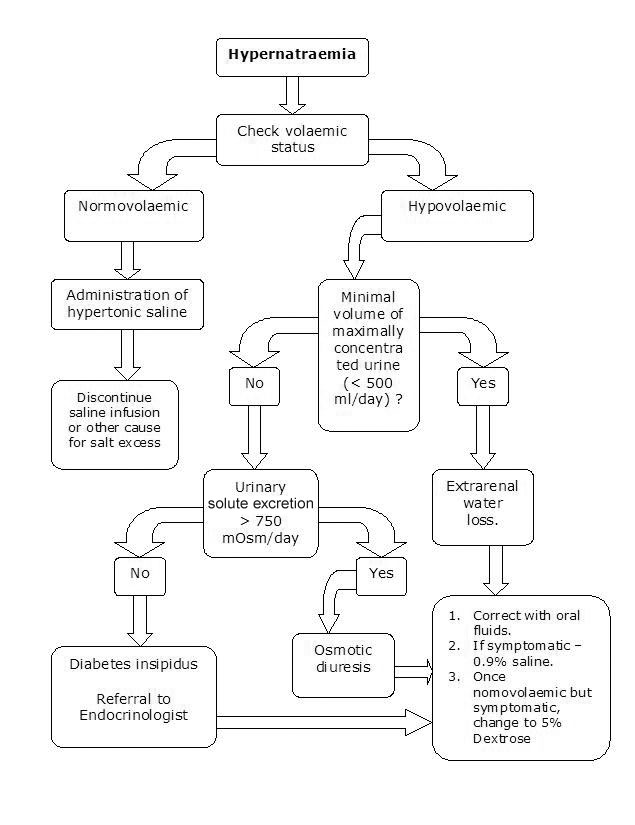

Treatment[edit | edit source]

- Involves identifying the underlying condition and correcting the hypertonicity.

- The goal of therapy is to correct both the serum sodium and the intravascular volume.

- Fluids should be administered orally or via a feeding tube whenever possible.

- In patients with severe dehydration or shock, the initial step is fluid resuscitation with isotonic fluids before free water correction.

- Hypernatremia is corrected by calculating the free water deficit using specific formulas[1].

Concluding Remarks[edit | edit source]

- Hypernatremia occurs due to net water loss or excess sodium intake.

- It is more common in infants or elderly population with neurological or physical impairment.

- It is crucial to identify acute versus chronic onset hypernatremia before correcting the free water deficit.

- It is important to remember that hypernatremia should be corrected over 48 hours. Rapid correction can lead to cerebral edema and seizures[1].

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Sonani B, Naganathan S, Al-Dhahir MA. Hypernatremia. StatPearls [Internet]. 2020 Aug 26.Available from:https://www.statpearls.com/articlelibrary/viewarticle/23192/ (last accessed 5.12.2020)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Farkas J. Internet Book of Critical Care (IBCC).Available from:https://emcrit.org/ibcc/hypernatremia/ (accessed 5.12.2020)

- ↑ Adrogue HJ, Madias NE. Hypernatremia. New England Journal of Medicine. 2000 May 18;342(20):1493-9.Available from:https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/241094-overview (last accessed 5.12.2020)

- ↑ RCHM Hypernatremia Available from: https://www.rch.org.au/clinicalguide/guideline_index/Hypernatraemia/ (accessed 5.12.2020)

- ↑ Felig P, Johnson C, Levitt M, Cunningham J, Keefe F, Boglioli B. Hypernatremia Induced by Maximal Exercise. JAMA. 1982;248(10):1209–1211. doi:10.1001/jama.1982.03330100047029 Available from:https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/article-abstract/377513 (last accessed 6.12.2020)