Hip Osteoarthritis

Original Editors - <a href="User:Eric Robertson">Eric Robertson</a>, <a href="User:Kim Presiaux">Kim Presiaux</a>

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Hip osteoarthritis is a common type of <a href="http://www.physio-pedia.com/index.php5?title=Osteoarthritis">osteoarthritis</a>. Since the hip is a weight-bearing joint, osteoarthritis can cause significant problems. Hip osteoarthritis is caused by deterioration of the articular cartilage of the hip joint. Deterioration means a bone on bone contact in the hip, instead of cartilage to cartilage. The synovial fluid can decrease or disappear completely.

There is too much broken cartilage, and not enough created.

There are several risk factors[1]: (Level of evidence: 3A)

- Previous hip injury: If you ever had a previous hip injury, there is a bigger chance that you get hip OA.

- Previous fracture, which changes hip alignment

- Genetics: It is possible that OA can be genetically transferable.

- Congenital and developmental hip disease

- Subchondral bone that is too soft or too hard

- Overweight: you have overweight if your BMI (body mass index) is between 25 and

29,9. Having overweight is a risk factor for OA, because there is a bigger load of weight

on the joint. - Occupation

- Age: When you get older, you have a higher risk for OA.

- Gender: The risk of OA is higher by women than men.

- Sport: To make your cartilage stronger, it is important to encumber your cartilage by doing

sports. Sports with a lower impact (like swimming) are good but they do not change a lot to

the composition of the cartilage. It is better to do high impact sports (like jumping). These

kinds of actions are better for the cartilage because they must absorb the impact. This

ensures that your cartilage becomes stronger. When you have a stronger cartilage, you

have a lower chance of having OA. - Menopause: There is a higher risk for OA in the menopause. It is not sure that this is due

to the hormonal changes. The menopause is common by women with an age of 55-60. - Sedentary Lifestyle: The most important thing for your articular cartilage is compression. If

there is not enough compression, the cartilage will be weak. This results in a higher risk for

having OA. - FAI (Femoro-acetabulair impingement) This impingement can lead to OA.

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

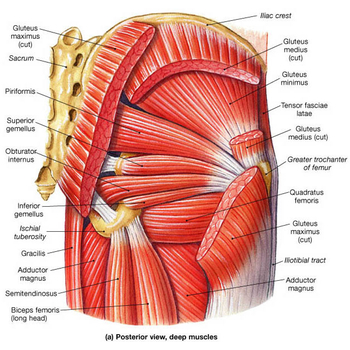

The hip joint is complex and is a synovial ball and socket joint , with the convex femoral head articulating with the concave acetabulum. Stability of the joint is achieved through a combination of muscle action and several ligaments forming a loose but strong joint capsule. Ligaments as the iliofemoral ligament, the ischiofemoral ligament and the pubofemoral ligament keep the femoral head at its place, in the acetabulum. Another ligamentum teres[29-EB:5] does not provide stability to the hip but offers a portion of blood supply to the femoral head in some individuals. The hip joint is extremely strong, due to its reinforcement by strong ligaments and musculature, providing a relatively stable joint.[30] Unlike the weak articular capsule of the shoulder, the hip joint capsule is a substantialcontributor to joint stability.[27][28] The muscles that play a great role in stabilizing the hip joint include m. gluteus medius, m. gluteus maximus, m. piriformis and deep core muscleswich are: m. gemellus superior, m.gemellus inferior, m.obturator externus, m. obturator internus, m. quadratus femorum.[31] The m. gluteus medius might be the most important reason for weakness causes . The iliopsoas muscle helps with the stability of the hip joint aswell.

There are a lot of muscles that contribute to the movement of the hip: the flexors(m. pectineus, m. rectus femoris, m. iliopsoas), the extensors(m. semitendinosus, m. semimembranosus, m. biceps femoris [long head], m. gluteus maximus), the adductors (m. adductor magnus, m. adductor longus, m. adductor brevis, m. gracilis, m. pectineus), the abductors (m. gluteus medius, m. tensor fasciae latae),the internal rotators ( tensor fasciae latae, m.gluteus minimus) and the external rotators (m.gluteus maximus, m. gemellus superior, m. gemellus inferior, m. obturator externus, m. obturator internus, m. quadratus femorum, m. piriformis)[31] The basic motions that are available in the hip joint are flexion , extension , adduction , abduction, internal rotation and external rotation. Full extension of the hip joint is the closed packed position because this position draws the strong ligaments of the joint tight, resulting in stability. The hip joint is one of the only joints where the position of optimal articular contact (combined flexion, abduction, and external rotation) is the loose-packed position, rather than the closed packed position, since flexion and external rotation tend to uncoil the ligaments and make them slack.[32]

The femoral head and acetabulum are covered by smooth cartilage , and the acetabulum contains a labrum[33-EB:1] with functions to facilitate movement and supportthe forces passed through the joint. The hip contains a femoral triangle as well where numerous vascular and neural structures, including the femoral vein, artery, and nerve pass through. There’s always a normal femoral inclination angle, from 120 to 125 degrees. The angle is closer to 125 in the elderly. An increase in this angle, greater than 125 degrees, results in coxa valga, and a decrease is called coxa vara. Eventually there is still the femoral angle of torsion which is between 12 and 15 degrees in normal people. An increase in this angle is termed Fig 2: Hip joint capsule anteversion, while a decrease in this angle is termed retroversion.[34]

External Link: [<a href="http://www.hipsknees.info/flash/HTML-HIPS/demo.html">Hip Anatomy Video</a>]

Epidemiology/etiology[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis is the most common disease causing joint complaints. Not only in women but also in men. It’s a disease that strikes many people worldwide, especially old persons. Research tells us that hip osteoarthritis has a prevalence of 11,5 percent in men and 11,6

percent in women. This is almost equal but when we look at knee osteoarthritis, we see that this is more prevalent in women [23].(level of evidence: 2A)

Then we have some information about the incidence of hip OA.[4] The incidence rate for female was found 2.4/1000 a year and for males 1.7/1000 a year. (level of evidence: 2B)

You have the personal level risk factors, described above, but you also have some joint level risk factors [22]. (Level of evidence: 3A) There are several causes for hip osteoarthritis:

1. Direct damage by trauma, arthritis, ...

2. Cartilage damage by metabolic process disorders (when there is a disrupt in homeostasis in the joint, more degradation of the cartilage matrix than synthesis)

3. The genetic factor (studies report the genetics are 60% of the risk)

4. Cartilage damage by repeated intra-articular bleedings

5. Congenital hip dislocation

6. Abnormality in stance of the joint (This will lead to a pathological loading pattern resulting in shear stresses)

7. Overload of the cartilage caused by obesity, prolonged overload, sensibility impediment

Additional to 6. :There is also more and more evidence these days that femoroacetabular impingement is an important factor causing hip osteoarthritis. This is what happens if the head of the femur scratches against the labrum what will lead to damage of the labrum and cartilage underneath. With the aid of time, this will result in degeneration of the joint.

A comparable problem is called developmental dysplasia of the hip. This is when the acetabulum doesn’t cover the femoral head enough and lead to instability of the femoral head. The result is shear forces onto the acetabular rim what also will lead to damage and degeneration of the hip joint.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The most important characteristic of hip osteoarthritis is that there’s damage to or loss of the articular cartilage[2]. Another typical characteristic is pain, especially pain that starts when the patient starts moving. This pain decreases when the patient keeps on moving or increases when they load the joint for too long or the wrong way. Later on, they will typically complain of a continuous pain and night pain.[3] (Level of evidence: A1)

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

A thorough patient history and physical examination should aid the clinican in his/her differential diagnosis. Pain location is often a good indicator of intraarticular versus extraarticular disorders. [4] The clinician should differentiate between a multitude of conditions such as: contusions, strains, athletic pubalgia, piriformis syndrome, hamstring syndrome, inflammatory disorders, snapping hip syndrome, bursitis, arthritis, septic arthritis, osteonecrosis, labral tears, fractures and dislocations, and tumors.

Patients with OA complain about joint pain, stiffness, reduced movement and local inflammation. Further on in the development of this disorder, people can be confronted with joint contractures, muscle atrophy and limb deformity. Early in the development of OA, the pain comes in episodes, as it progresses, the pain becomes more constant, also with episodes of sharp pain. Morning stiffness and pain at night can also be a symptom of advanced hip osteoarthritis. [8]

The hip is stiff and rigid, there is an unpleasant tension and a higher resistance while moving. This is something that does not last long, after moving a little bit around the stiffness goes away. The range of motion decreases, this is because of the pain and the stiffness of the hip. When you start moving it will be better, but not as good as in the beginning. There can also be a crispy noise if the hip is moving. [17][18]

Differential diagnosis[edit | edit source]

A thorough anamnesis and physical examination should aid a therapist in making his differential diagnosis. Patients will often come to the physiotherapist, complaining they have some pain issues. Pain location often gives a good indication whether it’s an intra-articular

or extra-articular disorder.

Possible intra-articular hip disorders are: FAI ( Femoroacetabular impingement), Osteoarthritis, avascular necrosis, fractures (fig.3), dislocations, Septic arthritis, labral tear, chondral defect and an injury of ligamentum teres.

Possible extra-articular hip disorders are: abductor and gluteus muscle injuries, sciatica, obturator and LFC nerve irritation, piriformis syndrome, snapping hip, bursa, trochanteric bursitis, an inguinal ligament strain and a disorder of the joint capsule. [10] (level of evidence 3)

Patients who probably have hip osteoarthritis have a constant pain and stiffness in the groin

region. This pain can be related to many causes, and doesn’t mean that every patient has arthritis. But the combination of groin pain and the limited movement and pain with internal rotation identifies people with this disorder. To make the diagnosis, radiography is usually done. If patients with osteoarthritis don’t have radiographic evidence, they often don’t receive a diagnosis of OA and don’t get the

treatment herefore. [8] (level of evidence 4)

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Hip osteoarthritis can also be seen on radiographs. The visible findings of this disorder are joint space narrowing, marginal osteophytes, subchondral sclerosis, and bone cysts. Magnetic resonance imaging is more effective in detecting early change in the bone

structure, such as focal cartilage defects and bone marrow lesions in the subchondral bone. [23] ( level of evidence 2A)

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The first test was the hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS). This is a questionnaire which is used to gain the patients' history about their hip and associated problems, as well to evaluate symptoms and functional limitations related to the hip

during a therapeutic process. There are other questionnaires that can be used to get the patients opinion like Western

Ontario and McMaster universities osteoarthritis index (WOMAC)[36], the algofunctional index (AFI), the intermittent and constant osteoarthritis pain index (ICOAP), lequesne index, 6-minute walk test,timed up and go test and the patients specific complaintslist (PSC).

The HOOS test judges functions and anatomical qualities combined with activities and participation. This is recommended when you are talking of hip disability with or without osteoarthritis. This test is meant to be used over short and long term intervals to view changes induced by treatment. It looks at the changes over a year time or at post traumatic osteoarthritis changes.

The HOOS questionnaire is a very simple test, which is user friendly and only takes 7-10

minutes to complete. The score consists of 40 items assessing 5 subscales: 5 separate patient-relevant dimensions: Pain (P), Symptoms (S), Activity limitations daily living (ADL), Function in sport and recreation (SP) and hip related quality of life (QOL). To interpret the score, the outcome measure is transformed in a worst to best scale from 0 to 100, with 100 indicating no symptoms and 0 indicating extreme symptoms. To calculate the total HOOS score the subscales need to be summed up, using following formula for all dimension: 100 – [(patient's score of the subscale x 100)/(total score of the subscale)]

This test has a high reliability , a good validity except for the floor and ceiling effects, a high responsiveness thanks to the addition of two subscales(SP and QOL).[35]

Medical management[edit | edit source]

Osteoarthritis is a common joint disorder, and the prevalence only increases with the aging of the population. This goes hand in hand with the increase of THR. THR, total hip replacement, is a successful orthopaedic procedure in the treatment of hip osteoarthritis, when the conservative therapy has failed. The number of total hip replacements per year increases by 73% overall. For those between 45 and 64 years, the

total number of THR increases with 123% and 54% for people between 65 and 84 years old.

In THR, prosthetic substitutes replace the original hip joint partly or fully with the purpose to repair the hip joint. There is no age or weight limit in undergoing a total hip replacement, they have been performed successfully at all ages. But a hip replacement at higher age can result in a worse functional outcome, major technical difficulties and higher operative risks.

A good choice of implant and the right surgical technique are essential for a successful result.

A good focus on the patient is also very important, so all the elements that can have a bad impact on the result can be deleted. ( level of evidence 4) [7]

There are several techniques for implanting a prosthesis. In a study of Rosenlund et al. [26] ( level of evidence 1), they investigated the difference in outcome in the two most commonly approaches of hip replacement: the lateral and posterior approach. The lateral approach is set to have a reduced outcome in pain and physical function, and also in a decrease of strength of the adductor muscles. In a case-control study of Nilsdotter et al [27] ( level of evidence 3), they had the purpose to investigate the relevant outcomes of a patient after a total hip replacement, they were followed 3,6 years after the surgery. 57% reported a WOMAC score less than 40

preoperatively, only 5,4% did this at the final follow-up. There was a significant increase in this score between the preoperatively measurement and the final one. 31% had an increased WOMAC score of less than 10 after 3,6 years for pain or function or function and pain. 40 patients reported a increase in WOMAC score of less than 20. The experimental group had a worse score than the reference group.

Examination[edit | edit source]

The beginning of OA is characterized by limited abduction and rotation in the hip joint. Later on flexion, extension, and adduction become more difficult.

Physiotherapeutic examination [5]

1) Palpation of M. gluteus medius.

Position: patient lies on his side. Upper leg in adduction and flexion

OA: Zone of greater Trochanter is sensitive and painful.

2)Flexion and forced flexion

Position: patient lies on his back. The physiotherapist lifted one leg to flexion. The knee is

in flexion so there is not too much muscle tension. The pelvis has to be at the same place.

OA: Flexion is limited for the final degrees. [19]

3) Extension

Position: 1. Patient stands in prone. Physiotherapist stabilizes the pelvis and raises the

leg. or 2. patient lies on his chest and lift the leg with flexion in the knee. You need a

flexion in the knee for a lower tension from the muscles

OA: Amplitude is limited.

4) Abduction

Position: Patient lies on his back. Physiotherapist stabilizes the pelvis and

performs abduction.

OA: abduction is limited and painful when the physiotherapist goes to the final degrees.

5) Adduction

Position: Patient lies on his back. The physiotherapist lift one leg and performs an

adduction with the other leg. The leg has to be in a normal position, no rotations.

OA: Keeps normal amplitude. [20][21]

Hip osteoarthritis can be diagnosed by a combination of the findings from a history and physical examination, so we don’t need to expose the patient to unnecessary radiation in an X-ray. The most used criteria in the diagnosis of hip osteoarthritis are those from the

American College of Rheumatology, which includes two sets of clinical features. [23] ( level of evidence 2A)

Clinical Set A:

- Age: 50+

- Hip pain

- Hip internal rotation ≥ 15 degrees

- Pain with hip internal rotation

- Morning stiffness of the hip less than 60min

Clinical Set B:

- Age: 50+

- Hip pain

- Hip internal rotation < 15 degrees

Hip flexion ≤ 115 degrees

Later on, Sutlive et al. published a list of variables for detecting hip osteoarthritis in patients with unilateral hip pain. If there are 3 present variables out of the list of 5 variables, the chance of having OA is 68%. With 4 or 5 variables that are noticed, the

chance increases to 91%. The variables are positive when there’s pain or a limited range of motion in the tests. [18] (level of evidence 2A)

The five variables are:

- Flexion

- Internal rotation

- Scour test: external and internal rotation in abduction and adduction of the hip.

- Patrick’s or FABER test: flexion,abduction and external rotation of the hip.

- Hip flexion test

Physical Therapy Management

[edit | edit source]

Treatment goals:

- regain strength

- better coordination

- increase mobility

- improve balance

- improve stance

- improve stability

- higher flexibility

- Reducing pain

Treatment goals should be draught in cooperation between therapist and patient[24]. Not only long term goals should be formulated but also a couple of short term goals should be formulated to achieve some noticeable progression and give the patient a feeling of success

[23]. The goals above are rather theoretical and needed for the therapist but the patient can also set some more specific goals regarding the activities of daily living such as walking without pain, doing laundry, taking stairs, etc. [24] (level of evidence: 4)

Education and self-management[23] (level of evidence: 1A)

Education is an important element of the therapy. It’s necessary for the patient to get insight in what osteoarthritis is. Education can be done in several ways: discussion with therapist, websites, support groups and written materials.

Self-management can be a result of the education and is also important concerning the positive coping style of the patient. This will lead to a change in behavior, which is positive for the quality of life.

Education and self-management must ensure that the patient will have knowledge of osteoarthritis. It will also ensure the insight in: the consequences for ADL, the psychological factors, the importance of a healthy and active lifestyle and weight as an influent factor.

USUAL CARE[edit | edit source]

Activation of the circulatory:[6] (Level of evidence: A1) Massage and heat therapy (radioation, conductien or conversion) can cause a better blood circulation near the skin, subcutaneous, muscles, tendons, capsules and ligaments.

Passive exercises[7] (Should improve mobility and flexibility but little evidence is found that this will improve function of the patient. This should be combined with exercise therapy for gettin result) [24]. (level of evidence:2)

- Positions patient: supine, hip in 15-30° flexion, 15-30° AB, slight ER

Physiotherapist: perform 3-6 thrusts at the beginning of the first set then perform oscillations.

- Positions patient: supine with hip flexed

Physiotherapist: oscillatory passive mobilizations, applied caudally or laterally to the proximal thigh

- Position patient: Prone with knee flexed.

Physiotherapist: IR until contralateral pelvis rises, apply oscillatory force downwards to contralateral pelvis

- Firm effleurage stroke, deep frictions or sustained pressure trigger point release with the muscle on stretch.

Position patient: Prone. The hip is in 10-15 ° AB.

Physiotherapist: Perform caudally directed oscillations. May perform 3-6 thrusts at the beginning of the first set.

- Position patient: Supine with hip in flexion and adduction.

Physiotherapist: Use body weight to impart passive oscillations to the postero-lateral hip capsule through the long axis of the femur. Add more flexion, adduction, and/or internal rotation to progress.

- Massage of quads, hamstrings, psoas, adductors, abductors, gluteus-muscles

Active exercises (The objective here should be reducing pain and improving function of the hip)

- Knee to chest exercise (strengthens the abdominal muscles and improves the flexibility of the hip, back and neck) Patient lies on the floor with left leg straight and right foot flat on the floor. Grabs his knee and bring it toward to his chest, holds for 30seconds and switches legs.

- Bridging exercise ( strengthens buttock abdominal and hamstrings muscles) Patient lies on his back with knees bent and feet flat on the floor. While tightening abdominal muscles he lifts his pelvis slightly upwards. Hold for 15-20 seconds. Repeat 8-12 times.

- Balance exercises [8]

( Standing weight shifting forwards/ lateral, Standing in double leg stance on foam, Shuttle walking, Stairs) - Endurance exercises

Walk, cycle, swim

Aquatherapy (Hydrotherapy) (Level of evidence: A1) Passive and active mobilization could be done in water as well, by an indifferent temperature (35 degrees), in order to facilitaite recovery of the motorfuntion. In this situation, gravity is greatly reduced thus the burdensome weight and tension at the height of the effected joint will be reduced as well. Advice and education is important in treatment, tell the patient about their condition. Why does it occur? What's the treatment? What's the importance of exercise? This will make the patient have a clear understanding in his condition and will improve the healing process.[9] It’s also very important to tell the patient what they can and can not do. Behavioral graded activities (BGA) is an kind of treatment that contains normal exercise therapy comprising booster sessions. The long term effectiveness has been shown, but it is unclear whether this treatment has a better efficacy than usual care.[10] BGA intervention consists of 3 phases:[11]

- Starting phase: The physiotherapist will educate the patient about his condition. And there will be made a list of treatment goals and problematic activities.

- Treatment phase: increasingly difficult exercises.

- Integration phase: The physiotherapist will support and integrate behavioral changes.

What about balneotherapy(level of evidence: 1) and preoperative physiotherapy(level of evidence: 3)?

This can neither be discouraged nor recommended.

And what about ultrasound(level of evidence: 2), electrotherapy(level of evidence: 3)?

This can’t be recommended in hip osteoarthritis.

Electromagnetic field and low level laser therapy (LLLT) can decrease pain. (level of evidence: 1) But it cannot be recommended in the guidelines. (level of evidence: 4) [24]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Hoeksma HL, Dekker J, Ronday HK, Heering A, van der Lubbe N, Vel C, Breedveld FC, van den Ende CH. Comparison of manual therapy and exercise therapy in osteoarthritis of the hip: a randomized clinical trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004 Oct 15;51(5):722-9.

Peter WF, Jansen MJ, Hurkmans EJ, Bloo H, Dekker J, Dilling RG, Hilberdink W, Kersten-Smit C, de Rooij M, Veenhof C, Vermeulen HM, de Vos RJ, Schoones JW, Vliet Vlieland TP; Guideline Steering Committee - Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis. Physiotherapy in hip and knee osteoarthritis: development of a practice guideline concerning initial assessment, treatment and evaluation. Acta Reumatol Port. 2011 Jul-Sep;36(3):268-81.

French HP, Cusack T, Brennan A, Caffrey A, Conroy R, Cuddy V, FitzGerald OM, Gilsenan C, Kane D, O'Connell PG, White B, McCarthy GM Exercise and manual physiotherapy arthritis research trial (EMPART) for osteoarthritis of the hip: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2013 Feb;94(2):302-14. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2012.09.030

Abbott JH, Robertson MC, Chapple C, Pinto D, Wright AA, Leon de la Barra S, Baxter GD, Theis JC, Campbell AJ; MOA Trial team. Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized controlled trial. 1: clinical effectiveness. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2013 Apr;21(4):525-34. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2012.12.014.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

http://www.guidelines.gov/content.aspx?id=36893

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed?otool=vublib

http://apps.webofknowledge.com.ezproxy.vub.ac.be:2048/WOS_GeneralSearch_input.do?product=WOS&search_mode=GeneralSearch&SID=U2HYlXJGBQdVzdFFDhX&preferencesSave d=

https://scholar.google.be/?inst=vub.ac.be

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Depending on the severity of the condition, managment will vary from patient to patient. It is important that the clinician individualizes treatment to each of their patients in order to ensure optimal outcomes.

Recent Related Research (from <a href="http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/">Pubmed</a>)

[edit | edit source]

Rosenlund, Signe et al. “The Gait Deviation Index Is Associated with Hip Muscle

Strength and Patient-Reported Outcome in Patients with Severe Hip Osteoarthritis—

A Cross-Sectional Study.” Ed. Diego Fraidenraich. PLoS ONE 11.4 (2016): e0153177.

PMC. Web. 19 Dec. 2016.

Kemp, Joanne L et al. “A Phase II Trial for the Efficacy of Physiotherapy

Intervention for Early- Onset Hip Osteoarthritis: Study Protocol for a Randomised

Controlled Trial.” Trials 16 (2015): 26. PMC. Web. 19 Dec. 2016.

Nolwenn Poquet, Matthew Williams and Kim L. Bennell. Exercise for Osteoarthritis

of the Hip, American Physical Therapy Association. April 14, 2016.

Kim, Chan et al. “Association of Hip Pain with Radiographic Evidence of Hip

Osteoarthritis: Diagnostic Test Study.” The BMJ 351 (2015): h5983. PMC. Web.

20 Dec. 2016.

References[edit | edit source]

<span class="fck_mw_references" _fck_mw_customtag="true" _fck_mw_tagname="references" />

1. Prieto-Alhambra D, Judge A, Javaid MK, Cooper C, Diez-Perez A, Arden NK. “Incidence and risk factors for clinically diagnosed knee, hip and hand osteoarthritis: influences of age, gender and osteoarthritis affecting other joints.” Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2014;73(9):1659-1664. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203355.

2. Cyrus Cooper, Hazel Inskip, Peter Croft, Lesley Campbell, Gillian Smith, Magnus

Mclearn, and David Coggon Individual Risk factors for Hip Osteoarthritis: Obesity, Hip Injury and Physical Activity Am. J. Epidemiol. 1998 147: 516-522.

3. Ganz, R., Parvizi, J., Beck, M., Leunig, M., Nötzli, H., Siebenrock, K.A.

Femoroacetabular impingement – a cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2003 Dec;417:112–120.

4. Prieto-Alhambra D, Judge A, Javaid MK, Cooper C, Diez-Perez A, Arden NK. “Incidence and risk factors for clinically diagnosed knee, hip and hand osteoarthritis: influences of age, gender and osteoarthritis affecting other joints.” Annals of the rheumatic diseases. 2014;73(9):1659-1664. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203355.

5. Jackson KA, Glyn-Jones S, Batt ME, Arden NK, Newton JL. Assessing risk factors for early hip osteoarthritis in activity-related hip pain: a Delphi study. BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e007609. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-007609.

6. Brembo EA, Kapstad H, Eide T, Månsson L, Van Dulmen S, Eide H. Patient information and emotional needs across the hip osteoarthritis continuum: a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research. 2016;16:88. doi:10.1186/s12913-016-1342-5.

7. Bottai, Vanna et al. “Total Hip Replacement in Osteoarthritis: The Role of Bone

Metabolism and Its Complications.” Clinical Cases in Mineral and Bone Metabolism 12.3 (2015): 247–250. PMC. Web. 10 Dec. 2016.

8. Kim, Chan et al. “Association of Hip Pain with Radiographic Evidence of Hip

Osteoarthritis: Diagnostic Test Study.” The BMJ 351 (2015): h5983. PMC. Web. 10 Dec. 2016.

9. Wright, Alexis, and Michael A. O’Hearn. “Differential Diagnosis and Early

Management of Rapidly Progressing Hip Pain in a 59-Year-Old Male.” The Journal of Manual & Manipulative Therapy 20.2 (2012): 96–101. PMC. Web. 10 Dec. 2016.

10. Fernandez M, Wall P, O’Donnell J, Griffin D. Hip pain in young adults. Aust Fam Physician 2014;43(4):205–9.

11. NILSDOTTER A.K., LOHMANDER L.S., KLÄSSBO M., ROOS E.M., Hip disability and osteoarthritis outcome score (HOOS) – validity and responsiveness in total hip replacement, BMC Musculosketel Disord., May 2003, level of quality C

12. Ebert JR, Retheesh T, Mutreja R, Janes GC. THE CLINICAL, FUNCTIONAL AND BIOMECHANICAL PRESENTATION OF PATIENTS WITH SYMPTOMATIC HIP ABDUCTOR TENDON TEARS. International Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. 2016;11(5):725-737.

13. Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, Campbell J, Stitt LW. Validation study of

WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988; 15: 1833–40.

14. Abbott, J.H., Robertson, M.C., Chapple, C., Pinto, D., Wright, A.A., Leon de la Barra, S. et al, Manual therapy, exercise therapy, or both, in addition to usual care, for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized controlled trial. 1: clinical effectiveness. Osteoarthritis & Cartilage. 2013;21:525–534.

15. Book: REGINSTER et al. 'Osteoarthritis. Clinical and Experimental Aspects'. Springer,

Verlag Berlin Heiderlberg, 1999.

16. Book: CRIELAARD J.M., DEQUEKER J., FAMAEY J.P., FRANCHIMONG P., GRITTEN Ch.,

HUAUX J.P. et al. ‘Osteoartrose’. Brussel, België: drukkerij Lichtert; maart 1985.

17. DeAngelis NA, Busconi BD. Assessment and differential diagnosis of the painful hip.

Clinical Orthopaedics. 2003;406:11-18.

18. SUTLIVE et al. 'Development of a Clinical Prediction Rule for Diagnosing Hip

Osteoarthritis in Individuals With Unilateral Hip Pain'. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther.: September 2008;38(9):542-50.

19. Kim L Bennell, Thorlene Egerton, Yong-Hao Pua, J Haxby Abbott, Kevin Sims, Ben

Metcalf, Fiona McManus, Tim V Wrigley, Andrew Forbes, Anthony Harris, Rachelle Buchbinder, “EFFICACY OF A MULTIMODAL PHYSIOTHERAPY TREATMENT PROGRAM FOR HIP OSTEOARTHRITIS: A RANDOMISED PLACEBO-CONTROLLED TRIAL PROTOCOL”, 2010, BMC musculoskeletal disorder.

20. M.F. Pister, C. Veenhof, F.G. Schellevis, D.H. De Bakker, J. Dekker, "LONG-TERM

EFFECTIVENESS OF EXERCISE THERAPY IN PATIENTS WITH OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE HIP OR KNEE: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL COMPARING TWO DIFFERENT PHYSICAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS", Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 2010

21. cindy veenhof, albère j. a. köke, joost dekker, rob a. oostendorp, johannes w. j. bijlsma, maurits w. van tulder, and cornelia h. m. van den ende, "EFFECTIVENESS OF BEHAVIORAL GRADED ACTIVITY IN PATIENTS WITH OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE HIP AND/OR KNEE: A RANDOMIZED CLINICAL TRIAL", 2006, Arthritis

22. Murphy, Nicholas J., Jillian P. Eyles, and David J. Hunter. “Hip Osteoarthritis:

Etiopathogenesis and Implications for Management.” Advances in Therapy 33.11 (2016): 1921–1946. PMC. Web. 19 Dec. 2016.

23. Bennell, K., “Physiotherapy management of hip osteoarthritis Journal of Physiotherapy”, Volume 59, Issue 3, September 2013, Pages 145–157.

24. Peter WF, Jansen MJ, Hurkmans EJ, Bloo H, Dekker J, Dilling RG, Hilberdink W, Kersten-Smit C, de Rooij M, Veenhof C, Vermeulen HM, de Vos RJ, Schoones JW, Vliet Vlieland TP; Guideline Steering Committee - Hip and Knee Osteoarthritis. Physiotherapy in hip and knee osteoarthritis: development of a practice guideline concerning initial assessment, treatment and evaluation. Acta Reumatol Port. 2011 Jul-Sep;36(3):268-81.

25. Nilsdotter, A et al. “Predictors of Patient Relevant Outcome after Total Hip

Replacement for Osteoarthritis: A Prospective Study.” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 62.10 (2003): 923–930. PMC. Web. 20 Dec. 2016.

26. Rosenlund, Signe et al. “The Effect of Posterior and Lateral Approach on Patient-

Reported Outcome Measures and Physical Function in Patients with Osteoarthritis, Undergoing Total Hip Replacement: A Randomised Controlled Trial Protocol.” BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 15 (2014): 354. PMC. Web. 20 Dec. 2016 (level of evidence1).

27. Book: Dutton M. Orthopaedic: Examination, evaluation, and intervention. 2nd ed.

New York: The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc; 2008.

28. Book:Levangie P, Norkin C. Joint structure and function: A comprehensive analysis.

4th ed. Philadelphia: The F.A. Davis Company; 2005.

29. Anerson L. The anatomy and biomechanics of the hip joint. J Back Musculoskeletal

Rehabil. 1994;4(15):145-153.( evidence based:5)

30. Book:Levangie P, Norkin C. Joint structure and function: A comprehensive analysis.

4th ed. Philadelphia: The F.A. Davis Company; 2005.

31. Book: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum , Sobotta Atlas van de menselijke anatomie Deel 2: romp, organen, onderste extremiteit derde herziene druk Houten 2006

32. Book: Levangie P, Norkin C. Joint structure and function: A comprehensive analysis.

4th ed. Philadelphia: The F.A. Davis Company; 2005.fckLRfckLR

33. Crawford M, Dy C, Alexander J, et al. The 2007 Frank Stinchfield Award. The

Biomechanics of the hip labrum and the stability of the hip. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2007;465:16-22.( evidence based:1)

34. Book:Levangie P, Norkin C. Joint structure and function: A comprehensive analysis.

4th ed. Philadelphia: The F.A. Davis Company; 2005.

35. Sanne Delporte, Scott Buxton and Bridgit A Finley Physiopedia : Hip Disability and

Osteoarthritis Outcome Score

36. Oyemi Sillo and Ammar Suhail WOMAC Osteoarthritis Index

37. Figure 1: posterior view, deep muscles hip, (https://gmb.io/hips/)

38. Figure 2: joint capsule, (http://eorthopod.com/septic-arthritis-of-the-hip-in-children/)

39. Figure 3: fractured hip, (https://courses.washington.edu/bonephys/opclin.html)

40. Figure 4: Patrick’s test,( http://picsfair.com/faber-test.html)

41. Figure 5: Knee to chest, (http://spinegrouparizona.com/education/back-exercises.html)

42. Figure 6: Short bridge exercise, (http://www.fitstream.com/exercises/bridge-a6090)

43. Figure 7: Two-leg standing balance on board,

(http://www.sparkpeople.com/resource/exercises.asp?exercise=353)

- ↑ Book: REGINSTER et al. 'Osteoarthritis. Clinical and Experimental Aspects'. Springer, Verlag Berlin Heiderlberg, 1999.

- ↑ Book: CRIELAARD J.M., DEQUEKER J., FAMAEY J.P., FRANCHIMONG P., GRITTEN Ch., HUAUX J.P. et al. ‘Osteoartrose’. Brussel, België: drukkerij Lichtert; maart 1985.

- ↑ Book: CRIELAARD J.M., DEQUEKER J., FAMAEY J.P., FRANCHIMONG P., GRITTEN Ch., HUAUX J.P. et al. ‘Osteoartrose’. Brussel, België: drukkerij Lichtert; maart 1985.

- ↑ DeAngelis NA, Busconi BD. Assessment and differential diagnosis of the painful hip. Clinical Orthopaedics. 2003;406:11-18.

- ↑ CRIELAND, e.a., Osteoartrose, Lichtert, Brussel, 1985

- ↑ Book: CRIELAND J.M., DEQUEKER J., FAMAEY J.P., FRANCHIMONG P., GRITTEN Ch., HUAUX J.P. et al. ‘Osteoartrose’. Brussel, België: drukkerij Lichtert; maart 1985.

- ↑ ) Kim L Bennell, Thorlene Egerton, Yong-Hao Pua, J Haxby Abbott, Kevin Sims, Ben Metcalf, Fiona McManus, Tim V Wrigley, Andrew Forbes, Anthony Harris, Rachelle Buchbinder, “EFFICACY OF A MULTIMODAL PHYSIOTHERAPY TREATMENT PROGRAM FOR HIP OSTEOARTHRITIS: A RANDOMISED PLACEBO-CONTROLLED TRIAL PROTOCOL”, 2010, BMC musculoskeletal disorder.

- ↑ ) Kim L Bennell, Thorlene Egerton, Yong-Hao Pua, J Haxby Abbott, Kevin Sims, Ben Metcalf, Fiona McManus, Tim V Wrigley, Andrew Forbes, Anthony Harris, Rachelle Buchbinder, “EFFICACY OF A MULTIMODAL PHYSIOTHERAPY TREATMENT PROGRAM FOR HIP OSTEOARTHRITIS: A RANDOMISED PLACEBO-CONTROLLED TRIAL PROTOCOL”, 2010, BMC musculoskeletal disorder.

- ↑ ) Kim L Bennell, Thorlene Egerton, Yong-Hao Pua, J Haxby Abbott, Kevin Sims, Ben Metcalf, Fiona McManus, Tim V Wrigley, Andrew Forbes, Anthony Harris, Rachelle Buchbinder, “EFFICACY OF A MULTIMODAL PHYSIOTHERAPY TREATMENT PROGRAM FOR HIP OSTEOARTHRITIS: A RANDOMISED PLACEBO-CONTROLLED TRIAL PROTOCOL”, 2010, BMC musculoskeletal disorder.

- ↑ cindy veenhof, albère j. a. köke, joost dekker, rob a. oostendorp, johannes w. j. bijlsma, maurits w. van tulder, and cornelia h. m. van den ende, "EFFECTIVENESS OF BEHAVIORAL GRADED ACTIVITY IN PATIENTS WITH OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE HIP AND/OR KNEE: A RANDOMIZED CLINICAL TRIAL", 2006, Arthritis & Rheumatism

- ↑ M.F. Pister, C. Veenhof, F.G. Schellevis, D.H. De Bakker, J. Dekker, "LONG-TERM EFFECTIVENESS OF EXERCISE THERAPY IN PATIENTS WITH OSTEOARTHRITIS OF THE HIP OR KNEE: A RANDOMIZED CONTROLLED TRIAL COMPARING TWO DIFFERENT PHYSICAL THERAPY INTERVENTIONS", Osteoarthritis and Cartilage, 2010