Hip Dislocation

Original Editor - Annelies Noppe

Top Contributors - Annelies Noppe, Leana Louw, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Lokiru Paul, WikiSysop, Vidya Acharya, Anas Mohamed and Kirenga Bamurange Liliane

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Hip dislocation is the displacement of the femur head from the acetabulum. Most of the times this causes damage at the tissue around the hip. Traumatic hip dislocations is seen as medical emergencies and treatment should be sought as soon as possible.[1]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

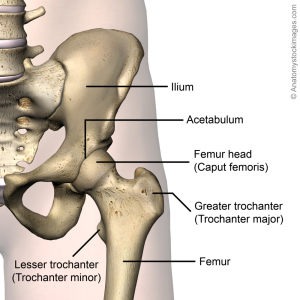

The ball-and-socket joint of the hip anatomy exist of the acetabulum and the femur head. The acetabulum has the shape of a cup and the femur head the shape of a ball.[2]

The hip is a weight bearing ball joint mainly functioning as support. The stability of the hip joint is provided mainly by the capsule and the surrounding muscles and ligaments. They stabilise the femur head in the acetabulum and ensure that the hip joint are able to move in all available planes.

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Characteristics[edit | edit source]

The following patients characteristics leads to an increased risk of developing a hip dislocation: [3]

- Female > male

- Alcohol abuse

- Various pre-operative disorders

- Older age:

- Decreased muscle mass reduces the stress on the hip prosthesis and decreases the natural protection against hip dislocation

- Increased risk of falling due to compromised balance

- Neuromuscular dysfunction associated with old age - e.g. neuropathy or cerebrovascular accident

- Cognitive impairments

- Great dexterity

- Poor follow instructions

- Increased tendency to fall

- Chronic hip instability[4]

Causes[edit | edit source]

The causes of hip dislocations can mainly be devided into two groups, mainly congenital and aquired hip dislocations.

Congenital hip dislocation (CHD)[edit | edit source]

Also known as developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH). All newborn babies have their hips assessed for DDH within a few days of birth and at six weeks in order for treatment to commence early if necessary.[5] CHD occurs with an incidence that vary between 1.5 and 20 per 1.000 births and is 8 times more commonly in girls than in boys.[6][7] This is explained by the greater mobility of the hip in women.[3] More than 80% of clinically unstable hips noted at birth have been shown to resolve spontaneously.[8]

Acquired hip dislocation[edit | edit source]

Young adults are most affected by traumatic hip dislocations, mostly caused by car accidents and is always the result of an external force with high intensity.[9] Another common mechanism is falling from a height.[5] Hip dislocations are thus rarely isolated, and often goes together with other injuries or fractures. With hip dislocations, the soft tissue around the hip, such as the muscles, ligaments and labrum are also damaged. Neural injuries may also be present.[5] Fractures to the acetabulum and femur head is most commonly associated with traumatic hip dislocations.[9] Hip dislocations are classified as either anterior or posterior, depending on the displacement of the femur head in relation to the acetabulum. Posterior hip dislocations are more common, and makes about 85-90% of the cases.[10] The position of the hip will be in flexion, adduction and internal rotation, with notable shortening of the leg. With anterior hip dislocations, the hip will be minimally flexed and positioned in abduction and external rotation.

Dislocation after hip replacement surgery has the highest incidence rate immediately after the surgery or in the first three months. This is normally caused by less trauma, usually falls or turning, moving into the contra-indicated positions, and putting stress on the capsule that was cut to do the replacement surgery. The incidence of hip dislocation following hip replacement surgery depends on patient, surgical and hip implant factors. In general, the larger the head of the femur post surgery, the less likely a patient is to experience dislocation.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

- Pain:[4]

- Severe pain is the most common symptom. With the separation of the femur head from the acetabulum, surrounding muscles and tendons can be damaged as well. Subsequent knee injuries might also be present.

- Radiating knee pain

- Swelling

- Leg length discrepancy and deformity:

- In most of the cases is the affected leg will appear shortened and the hip joint deformed

- Hip immobility:[4]

- Reduced hip range of motion

- Inability to walk as a result of pain and swelling

- Traumatic hip dislocations:[9]

- Male > female

- Posterior > anterior

- Neurological fallout (mainly in the sciatic nerve distribution) may be present

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Hip dysplasia

- Hip sublaxation

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- X-rays: AP pelvis and lateral

- To confirm dislocation and successful relocation

- Assess for associated fractures

- Progression of hip dysplasia

- CT:

- To rule out concomitant injuries in traumatic dislocations (e.g. acetabulum or femur head fractures)

- Clearance of lumbar spine[11]

Complications[edit | edit source]

Immediate:[5]

- Associated soft tissue injuries

- Neural injuries, especially to the sciatic nerve in posterior dislocations (present in about 10% of traumatic dislocations)

- Fractures, mostly to the femur head or acetabulum (mostly posterior wall)

Long term:[9]

- Avascular necrosis:

- Incidence of 1.7-40% is reducable to 0-10% if relocation is done within 6 hours post traumatic dislocation[12]

- Post-traumatic osteoarthritis

- Chronic dislocations

- Leg length discrepancy

Examination[edit | edit source]

- Observation:

- Hip dislocations can often be diagnosed by just looking at the hip. The hip will be shortenend, in external rotation, slight flexion and adduction in the more common posterior dislocations.

- Imaging (as explained above)

- Neurological assessment (to determine any associated neural injuries)

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Conginital dislocation[edit | edit source]

Conservative management[edit | edit source]

- Newborns: Flexion / abduction maneuvers .

- Bracing: A brace, splint or harness can be used to keep the hip in flexion and abduction for one or two months by the use of a brace, splint or harness.

- This aims to keep the femur head in the right position while the ligaments and bones grow and strengthen around it.

Surgery[edit | edit source]

Surgery is indicated for failed conservative management.

Surgery entails release the of the adductor longus muscle, lengthening the psoas tendon, and insertion of a Kirschner wire. This results in marked improvement in hip function and prevents complications later in life.[4] Total hip replacement surgery is an option later in life, when marked functional limitation and pain is present.

Acquired hip dislocation[edit | edit source]

A dislocated hip should be relocated as soon as possible, as the complication risk of avascular necrosis, neural damage and subsequent dislocations increases with the time between the dislocation and relocation.[9] The Allis maneuver is normally the reduction method of choice for posterior dislocations[9]

Non-surgical[edit | edit source]

Closed relocation of the hip is done by a traction force performed in the opposite direction of the dislocation, with the hip in 90° flexion. This should preferably be done under general or regional anesthesia and muscle relaxation to prevent greater damage to cartilage and soft tissue.[8] It may also be done in under anaesthetics in theater.[5] After the relocation, the stability of the hip should be tested very carefully. A period of bed rest might be recommended depending on the stability of the hip and the extent of the soft tissue injuries.

Surgical[edit | edit source]

Indications:

- Failed conservative relocation

- Instability following conservative relocation

- Associated fractures of the femur head or acetabulum

- Loose bone fragments in joint space after relocation

Hip arthroscopy can be used to evaluate intra-articular fractures and chondral injuries and to remove intra-articular fragments, Hip replacement surgery can also be considered if optimal stability is not achieved with relocation and fixation of the associated injuries.[9] Dislocation following hip replacement surgery might indicate revision surgery to ensure the stability of the hip in the long run.

Open reduction indications:[9]

- Used with challenging relocations or if any obstructions (e.g. loose fragments/soft tissue) is limiting closed reduction

- Deteriorating neurological signs following closed reduction (especially sciatic nerve function following posterior dislocation)

- Cases with proximal femur fractures, where manipulation of the leg is contra-indicated

Physiotherapy Management[edit | edit source]

It is important to take the time frames for soft tissue healing (and bone healing in cases with associated fractures) into consideration with rehabilitation following a hip dislocation. The orthopaedic surgeon will give guidance on weight bearing restrictions that might be present following the medical management of the hip. Full rehabilitation following hip dislocation can take 2-3 months.[5]

- Gait re-education: Initially with mobility assistive devices (walking frame/crutches) to limit weight bearing, and progression thereof

- Improve hip range of motion: Especially extension in children after the use of a brace/splint/harness that kept the hip in flexion

- Strengthening of muscles around the hip, with special focus on hip stabilizers

- Stretching

- Joint mobilization

- Graded return to activity/sport

See rehabilitation resources below.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Rehabilitation Guidelines for Surgical Hip Dislocation

- Surgical Hip Dislocation Rehabilitation Protocol

- Hip Surgical Dislocation Guidelines

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Hip dislocations are classified into congenial and acquired. Congenital hip dislocations, or developmental hip dysplasia can be successfully managed in children, but might cause problems later in life, when total hip replacement surgery might be indicated to improve function, leg length discrepancies and pain. Acquired, or traumatic hip dislocations are medical emergencies, and treatment should be sought as soon as possible. Relocation should ideally occur within 6 hours from the dislocation, in order to reduce complications. Traumatic dislocations are reduced either open or closed, and open or arthroscopy surgery might be indicated in cases with associated fractures. Physiotherapy plays an important role in the rehabilitation following a hip dislocation, in order to get the patients back to their previous level of function, and to prevent further dislocations.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Ortho Info. Hip dislocation. Available from: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/hip-dislocation (accessed 16/08/2020).

- ↑ Barlow TG. Early diagnosis and treatment of congenital dislocation of the hip. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. British volume 1962;44(2):292-301.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Van der Grinten M, Verhaar JA. Luxatie van totaleheupprothese; risicofactoren en behandeling. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. 2003:286-90.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Hung NN. Traumatic hip dislocation in children. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics B 2012;21(6):542-51.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Ortho Info. Developmental Dislocation (Dysplasia) of the Hip (DDH). Available from: https://orthoinfo.aaos.org/en/diseases--conditions/developmental-dislocation-dysplasia-of-the-hip-ddh (accessed 08/08/2020).

- ↑ Greenspan A. Orthopedic Radiology: A practical approach. Gower Medical Publ.:New York, 1988.

- ↑ Patel H. Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Preventive health care, 2001 update: screening and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. Cmaj 2001;164(12):1669-77.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Medscape. Hip dislocation. Available from: https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/86930-overview (accessed 09/08/2020).

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 Lima LC, Nascimento RA, Almeida VM, Façanha Filho FA. Epidemiology of traumatic hip dislocation in patients treated in Ceará, Brazil. Acta ortopedica brasileira 2014;22(3):151-4.

- ↑ DeLee JC. Fractures and Dislocations of the Hip. In: Rockwood CA Jr, Green DP, Bucholz R (eds): Fractures in Adults. Vol 2. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven, 1996. p. 1756-1803.

- ↑ Larson DE. Gezin en gezondheid. Cambium BV:Zeewolde, 1995.

- ↑ Bucholz R, Heckman JD. Rockwood e Green fraturas em adultos. In: Rockwood e Green fraturas em adultos, 2006: pp. 2263-2263.