Herpes Zoster

Original Editors - Heather Lindsey and Kaycee Stone from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Kaycee Stone, Heather Dixon, Lucinda hampton, Donald John Auson, Kim Jackson, Elaine Lonnemann, Wendy Walker, WikiSysop, Chelsea Mclene, Nupur Smit Shah and Evan Thomas

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

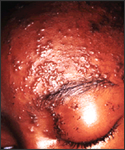

Herpes Zoster, commonly called Shingles, is characterized by a painful rash with blisters.[1] It results from reactivation of the dormant varicella-zoster virus, also known as chickenpox, that reactivates within sensory ganglia.[2] The painful rash is associated with an involved nerve root and its associated cranial or spinal nerve dermatome that occurs 3-5 days after transmission of the virus. It will usually only be present on one side of the body because it typically will not cross midline. However, it can affect both sides of the body at different dermatome levels. Patients will typically experience 1-2 days of pain, itching, and hyperesthesia before the skin lesions are noticed.[3]

Prevalence[edit | edit source]

Shingles will affect 1 in 3 people in the United States, with approximately 1 million cases each year.[4] Half of the people affected are over the age of 60,[4] but people of any age can develop herpes zoster if they have previously contracted the varicella-zoster virus.[5]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation

[edit | edit source]

At first, there is only pain, tingling, or burning before a rash appears.[1] The pain that the patient may experience can be constant or intermittent and will vary from light burning to a deep visceral sensation.[3] This is generally on one side of the body. The rash appears as red areas, then blisters that break and form crusts. This rash usually lasts two to three weeks and often affects an area from the spine to the chest or abdomen, as well as the ears, face, or eyes.[1] The rash can be widespread, like chickenpox, in cases involving an immunocompromised patient.[4] Other associated symptoms include flu-like symptoms such as fever, chills, malaise, headache, joint pain, and swollen glands.[1] If there is cranial nerve involvement then the patient may experience hearing or vision loss.[3]

Postherpetic neuralgia, which is pain lasting longer than 90 days following the initial herpes zoster rash, was found in 24% of patients in a quality of life study by Drolet et al. Acute pain and postherpetic neuralgia were most commonly associated with anxiety, depression, difficulty sleeping, and decreased ability to participate in activities of daily living.[6] Early interventions can help decrease the risk of developing postherpetic neuralgia.[3]

Associated Co-morbidities[edit | edit source]

Immunocompromised people, like people undergoing treatment for cancer, leukemia, lymphoma, HIV, and patients on immunosuppressive drugs are at an increased risk of developing shingles.[4] Others who are at a higher risk include patients who have had a transplant, have never had the chickenpox virus, or are under a lot of stress. There have been two different age groups that have been identified as having a higher incidence of acquiring shingles. These two groups are college-aged young adults and adults over 70 years old.[3]

Medications[edit | edit source]

Acyclovir, valacyclovir, and famciclovir are antiviral medications that are commonly prescribed to treat shingles to shorten the duration and ease the severity of the outbreak. Analgesics may also be prescribed to help with the pain related to shingles.[4] Other medications that are used to treat shingles include steroids and anticonvulsants.[7]

Diagnostic Tests/Lab Tests/Lab Values[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis is generally made based upon an examination of the skin and taking medical history. A skin sample may be taken to determine if the skin is infected by the varicella-zoster virus. Health care providers may run blood tests, which will not diagnose Herpes Zoster, but will show elevated white blood cells and antibodies to the virus that causes chicken pox.[1]

Etiology/Causes[edit | edit source]

Herpes Zoster is caused by the dormant varicella zoster, also known as chickenpox, becoming active again, often years following the initial incidence of the infection.[1] The dormant virus becomes active when the patient's immune system declines due to immunosuppression or aging.[5] It is acquired from direct contact with infected airborne droplets or with vesicular fluid.[8]

Systemic Involvement[edit | edit source]

Systemic involvement is not generally noted except in patients that are already immunocompromised due to autoimmune disease or taking medication or treatments that decrease immune function.

- A study by Che et al. found that patients with rheumatoid arthritis who were receiving anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy, or TNF blockers, were at a higher risk for developing herpes zoster up to 61%, including severe infections.[9]

- In the HIV population, herpes zoster occurs at a higher incidence rate, especially complicated herpes zoster with systemic involvement and a rash affecting multiple dermatomes, although this has decreased from previous incidence rates due to anti-retroviral therapy.[10]

- Patients diagnosed with systemic lupus erythmatosus and herpes zoster have been documented to have visceral involvement, which included meningeal spread and pancreatitis in a study by Isgro et al.[11]

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

Shingles can be treated conservatively using nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or wet dressings with 5% aluminum acetate. These dressings should be applied for 30-60 minutes and be done 4-6 times each day. Lotions such as calamine can also be used to help relieve symptoms.[7]

The Varicella-zoster virus vaccine is used as a preventative measure for shingles.[7] A literature update by Dworkin et al. for the Mayo Clinic recommends pharmacological management via implementation of the vaccine as a preventative intervention. The vaccine decreases the risk of developing herpes zoster by half, and thus, reduces the risk of neuropathic pain.[12] In terms of treating postherpetic neuralgia (PHN), the authors suggest topical lidocaine administered via a 5% patch or as a gel to be a tolerable and first-line treatment for localized PHN. The authors did not find antidepressants to be an effective treatment for PHN in the literature or in their clinical experience. Clinical trial research suggests that high dose capsaicin topical patches may produce a reduction in symptoms for a few months, but long-term effects weren't known at the time of the literature review. Conflicting evidence exists for the benefits of botulinum toxin injections for neuropathic pain resulting from herpes zoster. [12]

Physical Therapy Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

TENS may be used to treat acute pain and reduce the healing time of the rash associated with herpes zoster. It can be used safely with antiretroviral treatment or as the only treatment. A recent study in 2012 found that TENS may be at least as effective as traditional pharmacological therapies, and it may help reduce or prevent the risk of developing postherpetic neuralgia. TENS therapy generally involves placing two electrodes on the dermatome affected by herpes zoster for 30 minutes five times per weeks for a period of time up to three weeks. Suggested electrical output was 1-5 mA with frequencies ranging from 20 to 40 Hz.[13]

If the facial nerve is affected by herpes zoster and peripheral facial palsy results, facial exercises have been found to be effective. These exercises include exercises to stimulate functional movement in the face, achieve symmetry, to improve motor control, reduce synkinesis, improve perception of movement, and promote emotional expression. Mirror therapy, mime therapy, facial muscular re-education, and Kabat's exercises were found to be effective means of facial rehabilitation techniques.[14]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Herpes simplex virus may mimic herpes zoster if it is recurrent and occurring in a dermatomal pattern. Laboratory tests are needed to avoid the misdiagnosis[15] Lymphangioma circumscriptum can also mimic the rash associated with shingles.[16]

Case Reports/ Case Studies[edit | edit source]

www.hindawi.com/journals/criid/2013/647486/

safampract.co.za/index.php/safpj/article/viewArticle/2553

Resources[edit | edit source]

Patient Resources:

www.cdc.gov/shingles/resources-refs.html

Support Group:

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=1nOuz78nMHPR_ZCWRJxY8p2apDflYm9C9gr2U0PzDU8JTDvMOp: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 PubMed Health. Shingles: herpes zoster. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0001861/ (accessed 4 March 2014).

- ↑ Oxman MN, Levin MJ, Johnson GR, Schmader KE, Straus SE, Gelb LD, et al. A Vaccine to prevent herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia in older adults. N Engl J Med 2005; 352:2271-84.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Goodman CC, Snyder TEK. Differential diagnosis for physical therapist screening for referral. 5th ed. Missouri: Elsevier Saunders, 2013.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Centers for Disease Control. Shingles (herpes zoster). http://www.cdc.gov/shingles/about/index.html (accessed 4 March 2014).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Sampathkumar P, Drage LA, Martin DP. Herpes zoster (shingles) and postherpetic neuralgia. Mayo Clin Proc 2009;84(3): 274-280.

- ↑ Drolet M, Brisson M, Schmader KE,Levin MJ,Johnson R,Oxman MN, et al. The impact of herpes zoster and postherpetic neuralgia on health-related quality of life: a prospective study. CMAJ 2010; 182: 1731-6.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Medscape. Herpes zoster treatment & management. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1132465-treatment (accessed 13 Mar 2014).

- ↑ Goodman CC, Fuller KS. Pathology implications for the physical therapist. 3rd ed. Missouri: Saunders Elsevier, 2009.

- ↑ Che H, Lukas C, Morel J, Combe B. Risk of herpes/herpes zoster during anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine 2013:1-7.

- ↑ Blank LJ, Polydefkis MJ, Moor RD, Gebo KA. Herpes zoster among persons living with HIV in current ART era. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2012;61(2):203-7.

- ↑ Isgro J, Levy DM, LaRussa P, Imundo LF, Eichenfield AH. Descriptive analysis of herpes zoster in childhood-onset systemic lupus erythmatosus. Pediatr Rheumatol 2012;10(suppl 1):A25.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Dworkin RH, O'Connor AB, Audette J, Baron R, Gourlay GK, Haanpaa ML, et al. Recommendations for the pharmacological management of neuropathic pain: an overview and literature update. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85(Suppl 3):S3-S14.

- ↑ Kolsek M. TENS-an alternative to antiviral drugs for acute herpes zoster treatment and postherpetic neuralgia prevention. Swiss Med Wkly 2012;141:1-5.

- ↑ Pereira LM, Obara K, Dias JM, Menacho MO, Lavado EL, Cardoso JR. Facial exercise therapy for facial palsy: systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Rehab 2011;25:647-58.

- ↑ Koh MJ, Seah PP, Teo RY. Zosteriform herpes simplex. Singapore Med J 2008;49:e59-60.

- ↑ Patel GA, Siperstein RD, Ragi G, Schwartz RA. Zosteriform lymphangioma circumscriptum. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Panonica Adriat 2009;18:179-82.