Heart Failure

Original Editors - Students from Glasgow Caledonian University's Cardiorespiratory Therapeutics Project.

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton, Jayati Mehta, Vidya Acharya, Doireann Church, Caoimhe Mackey, Kim Jackson, Areeba Raja, Admin, WikiSysop, 127.0.0.1, Evan Thomas, Michelle Lee, Karen Wilson and Aminat Abolade

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

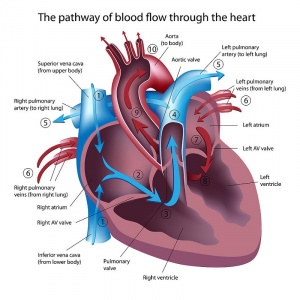

Heart failure (HF) is a term used to cover three distinctive clinical presentations. The human heart has four chambers (two atria and two ventricles). In a normal heart, there are open connections between the right atrium and right ventricle through the tricuspid valve and also between the left atrium and left ventricle through the mitral valve. There are no open connections between the two atria and the two ventricles. Therefore, the left and right halves of the heart actually function as two hearts.

- The failure of the left half causes a distinct set of symptoms and signs which is called left heart failure.

- The failure of the right half causes a distinct set of features collectively called right heart failure.

- The combination of the two is known as congestive heart failure.

It is important to understand that congestive heart failure is a type of heart failure and not a totally different condition[1].

Heart failure is a major public health concern in countries worldwide. The increasing prevalence of heart failure in the population is most likely secondary to the aging of the population, increased risk factors, better outcomes for acute coronary syndrome survivors, and a reduction in mortality from other chronic conditions[2]. It is estimated that globally more than 25 million people are affected by HF.[3]

Causes[edit | edit source]

Causes for heart failure can be many. There are three main pathologies that lead to heart failure; pump failure, increased pre-load, and increased after-load.

- Pump failure can occur due to myocardial infarction, cardiomyopathy, poor heart rate, poor contractility and poor filling.

- Preload may go up due to fluid overload, aortic and pulmonary regurgitation.

- Afterload may go up due to excessively high systemic blood pressure, aortic and pulmonary stenosis.[1]

Types of HF[edit | edit source]

Left Ventricular Failure (LVF): the most common form of heart failure.

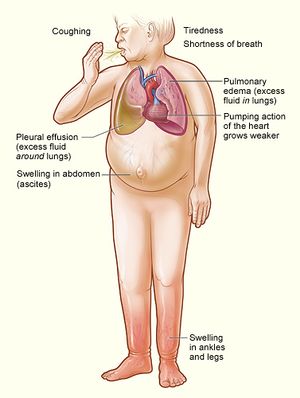

- Gradually pushes up the pressure in the left atrium and pulmonary vascular system.

- The resulting pulmonary hypertension may force fluid into the alveoli creating pulmonary oedema.

Therefore, the patient presents with dizziness, lethargy, poor exercise tolerance, syncope, fainting attacks, amaurosis fugax (due to poor output), dyspnea, orthopnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea and pink frothy sputum (due to increased pulmonary venous pressures)[1].

Right Ventricle Failure (RVF)

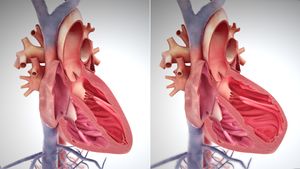

- Image R: A depiction of heart enlargement during RVF, normal heart L, overstretched muscles heart R.

Right heart failure causes poor pulmonary circulation and increased systemic venous pressures. This generally occurs secondary to cardiopulmonary disorders such as pulmonary hypertension, right ventricle infarction, congenital heart disease, pulmonary embolism or COPD.[4]

Therefore, the patient presents with dependent edema, enlarged liver, elevated jugular venous pressure (due to increased systemic venous pressure), reduced exercise tolerance and dyspnea (due to poor pulmonary circulation).[1]

Biventricular heart failure

Heart failure most typically occurs on the left side of the heart. When the damage expands and also impacts the right side it is referred to as biventricular heart failure. Symptoms can be reflective of both left and right-sided heart failure, including shortness of breath and swelling due to a build-up of fluid[5]

The 12 minute video below is on the classification of HF according to severity.

Epidemiology[edit | edit source]

Heart failure is a significant public health problem with a prevalence of over 5.8 to 6.5 million in the U.S. and around 26 million worldwide[7]. HF is the world’s leading cause of hospitalization and results in a burden that is felt at every level of healthcare:

- For systems and healthcare workers assisting with greater numbers of very ill patients

- For health economies with increasing costs, particularly in a disease area where rehospitalizations are so high: 50% are readmitted within six months of discharge

- For patients who are diagnosed with a progressive disease without a cure, and their carers

The prognosis for those diagnosed with heart failure is poor:

- 17-45% of patient deaths occur within one year of hospital admission

- 45-60% of deaths occur within five years of admission

But heart failure also takes its toll on people’s daily lives and their families, often resulting in a reduced ability to lead the same lifestyles as before.[8]

Aetiology[edit | edit source]

There are multiple risk factors for heart failure, including older age (65 years or over), being male, having a family history of the condition, or having certain underlying conditions, particularly myocardial infarction , cardiac valve insufficiency (leaking) or stenosis (narrowing), and diabetes. Certain lifestyle factors—such as tobacco smoking, alcohol consumption, physical inactivity, and a diet that predisposes individuals to high cholesterol and high blood pressure—also raise the risk of developing heart failure[3].

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

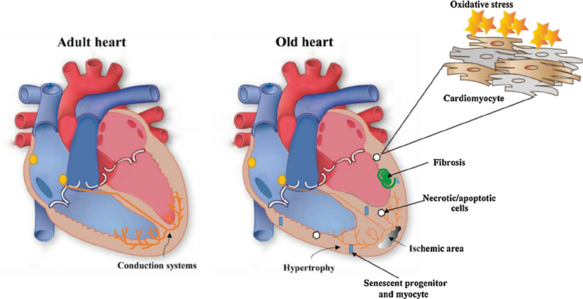

The pathophysiology of HF is complex and includes structural, neurohumoral, cellular, and molecular mechanisms activation to maintain physiologic functioning (maladaptation, myocyte hypertrophy, myocyte death/apoptosis/regeneration, and remodeling).[7]

- In response to increased load, the left ventricular myocardium hypertrophies.

- The greater size and number of myocytes raise myocardial oxygen demand and increases diffusion distance for oxygen.

- Some muscle fibres become ischaemic, leading to patchy fibrosis, stiffness and reduced contractability[9].

- The workload causes the ventricle to stretch and dilate, leading to further force being required to maintain cardiac output[9].

- Systolic failure is by reduced ejection fraction and diastolic failure is by reduced end-diastolic volume.

- Metabolic effects include loss of bone mineralisation, skeletal muscle and fat[4].

- The stiffness and reduced contractibility push up end-diastolic pressure, which is transmitted back along the pulmonary veins to the pulmonary capillaries, which causes fluid to be forced into the interstitial spaces and, if severe, into the alveoli, causing pulmonary oedema.

- The increased pulmonary vascular pressure raises the afterload of the right ventricle, in the same way as chronic systemic hypertension raises the afterload of the left ventricle[10].

- Hypertrophy, patchy fibrosis, stiffness and reduced contractibility of the right ventricular myocardium then ensues, as with left ventricle, and congestive cardiac failure develops[9].

See also Cardiovascular Considerations in the Older Patient

Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment of heart failure is complex and multifaceted. Of prime importance is treatment of the specific underlying disease (such as hypertension, valvular heart disease, or coronary heart disease). Prescribed medications are usually aimed at blocking the adverse effects of the various neurologic, hormonal, and inflammatory systems activated by heart failure.

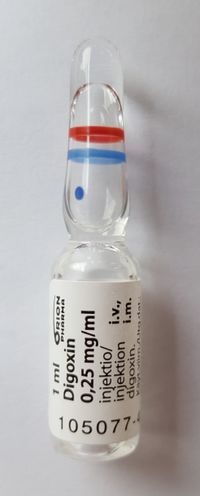

These are generally drugs in the class of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors to lower blood pressure and decrease the heart’s workload, beta-adrenergic blockers (beta-blockers) to stabilize the heartbeat, aldosterone antagonists to decrease salt retention, and vasodilators to relax the smooth-muscle lining of the veins and arteries. Diuretics are prescribed to remove excess fluid. Digoxin and digitoxin are commonly prescribed to increase the strength of heart contraction[3].

Patients are also advised to limit their intake of salt and fluids, avoid alcohol and nicotine, optimize their body weight, and engage in aerobic exercise as much as possible. Much can be done to prevent and treat heart failure, but ultimately the prognosis depends on the underlying disease causing the difficulty as well as the severity of the condition at the time of presentation.

See also Pharmacological Management of Heart Failure

Physiotherapy[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy is important in the management of heart failure. The cornerstone of physiotherapy management is cardiac rehabilitation. In patients undergoing heart surgery, physiotherapy can also help with recovery after surgery.

Up until the late 1980s, exercise was considered unsafe for the patient with HF. It was unclear whether any benefit could be gained from rehabilitation, and concern also existed regarding patient safety, with the belief that additional myocardial stress would cause further harm. Since this time, considerable research has been completed and the evidence resoundingly suggests that exercise for this patient group is not only safe but also provides substantial physiological and psychological benefits. As such, exercise is now considered an integral component of the non pharmacological management of these patients

Aims of effective treatment for heart failure[edit | edit source]

- Strengthen the heart

- Improve symptoms

- Reduce the risk of a flare-up or worsening of symptoms

- Improve Quality of Life

- Offer longevity

Recent research findings[edit | edit source]

- Systematic review and meta-analysis show a significant effect of aerobic and resistance training on peak oxygen consumption, muscle strength, and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure with a reduced left ventricular ejection fraction[11]

- A study published in the Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention 2020, comparing the effects of β-blockers and non-β-blockers on Heart Rate (HR) and Oxygen Uptake (VO2) during exercise and recovery in older patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) demonstrated no significant differences in values (HRpeak, HRresv, HRrecov, or VO2) between both the groups, along with significant correlation between HRresv and VO2peak, suggesting the efficacy of these measures in prognostic and functional assessment and clinical applications, including the prescription of exercise, in elderly HFpEF patients[12].

- Studies show a contrasting effect of aerobic training and resistance training on some echocardiographic parameters in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. While aerobic training was associated with evidence of worsening myocardial diastolic function, this was not apparent after resistance training. Further studies are indicated to investigate the long-term clinical significance of these adaptations[13].

- А single-blind, prospective randomized controlled trial suggests: modified group-based High-intensity aerobic interval training (HIAIT) intervention showed more considerable improvement as compared to moderate-intensity continuous training (MICT) in the rehabilitation of patients with chronic heart failure (CHF). Physical and rehabilitation medicine (PRM) physicians should apply Group based Cardiac intervention in routine cardiac rehabilitation (CR) practice[14].

- An article published online (March 2020) suggests positive outcomes with the High-intensity interval training (HIIT) for patients with heart failure along with preserved ejection fraction[15].

- A study assessing patients carrying out 5-months cardiac rehabilitation CR showed a lower rate of clinical events with higher maximal inspiratory pressure, suggesting that the changes in respiratory muscle strength independently predicted the occurrence of clinical manifestations in patients with Heart Failure HF[16].

- The results of a cross-sectional study in Spain by Raul Juarez-Vela et al. show that Heart Failure patients depend on others' care, especially for moving, dressing, personal hygiene, participating in daily and recreational activities, suggesting a weaker relationship between care dependency and the patients' physical deterioration[17].

Multidisciplinary team members[edit | edit source]

The other members of the MDT are vast but include

- Surgeons and consultants - They operate if needed. Numerous operations are available and may be suitable for certain patients. For example, Heart Valve Surgery, Angioplasty or Bypass, Left Ventricular Assist Devices, Cardiac Inplant Electronic Devices, Heart Transplant. However, this is individual and would need to be discussed with the consultant in charge of the case.

- Nutritionists - They work out a diet plan to suit the individual needs of the patient. As diet is a risk factor for CHD this is an extremely important member of the MDT for further prevention.

- Counselor - As Heart failure is normally a lifelong condition the patient may have difficulty coming to terms with the impact this will have on their life. A counsellor will be available for sessions on coping with the disease.

- Personal Trainer- As with a Physiotherapist will help to provide a more balanced lifestyle and improve fitness levels. This is something that will not only give the patient goals to work towards but also important social interaction with someone who is seen as less of a medical figure and therefore adds more normality to the individuals day to day life.

- Family and Friends- This support network is an extremely important factor contributing to recover of a patient and should not be overlooked.

The list of people involved in this team is huge and is not exhaustive in this piece, however, Pharmacists, Social Groups, GP’s, Nurses and Podiatrists are all members of this MDT. Recovery cannot occur without input and communication from every member of the team.

Prevention[edit | edit source]

There are many factors that increase the risk of developing heart failure. And with some lifestyle changes and sometimes drug intervention this risk could be dramatically reduced. Hypertension and smoking are major risks for heart failure.

- Stop smoking. Quitting smoking is noted as the single best way to reduce risk of heart failure. Smoking has many physiological effects forcing the heart to walk harder.

- Reduce blood pressure. High blood pressure increases the work demand put on the heart to transport blood around the body, this increased work causes a hypertrophic reaction of the heart muscle, eventually leading to a weakened or stiff heart.

- Reduce Cholesterol Level. High levels of cholesterol can cause furring and narrowing of the arteries termed atherosclerosis and eventually heart failure.

- Lose weight. Being overweight increases demand placed on the heart and increases risk of heart failure and attack.

- Eat a healthy diet. A healthy diet can help reduce your risk of developing coronary heart disease and therefore heart failure.

- Keep active. Regular physical activity will help keep the heart healthy and also maintain a healthy weight.

- Reduce Alcohol intake. Drinking excess of the recommended amount of alcohol per week can increase your blood pressure. Heavy drinking for long periods of time can cause damage to your heart muscle leading directly to heart failure.

- Cut your salt intake. Excessive salt intake increases blood pressure and again, increases stress put on the heart.

Viewing[edit | edit source]

The below is a 12 minute video on HF

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Diffence between Difference Between Heart Failure and Congestive Heart Failure Available:https://www.differencebetween.com/difference-between-heart-failure-and-vs-congestive%C2%A0heart-failure/ (accessed 1.6.2021)

- ↑ King KC, Goldstein S. Congestive Heart Failure and Pulmonary Edema. StatPearls [Internet]. 2021 Jan 20.Available: https://www.statpearls.com/ArticleLibrary/viewarticle/19880(accessed 2.6.2021)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Britannica Heart Failure Available: https://www.britannica.com/science/heart-failure(accessed 1.6.2021)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hough, A. Physiotherapy in Respiratory and Cardiac Care: An Evidence Based Approach. Hampshire. Cengage Learning EMEA; 2014.

- ↑ Health Union Heart Failure Available from: https://heart-failure.net/left-right-biventricular/ (last accessed 12.8.2020)

- ↑ classification system of heart failure

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hajouli S, Ludhwani D. Heart Failure And Ejection Fraction 2020.Available from:https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553115/ (last accessed 11.8.2020)

- ↑ World heart federation CVD road map Available: https://world-heart-federation.org/cvd-roadmaps/whf-global-roadmaps/heart-failure/ (accessed 1.6.2021)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Dickstein, K.ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. European Journal of Heart Failure. 2008. Aug;10:933-989.

- ↑ British Society for Heart Failure. National Heart Failure Audit. London. November 2013.

- ↑ Neto MG, Durães AR, Conceição LS, Roever L, Silva CM, Alves IG, Ellingsen Ø, Carvalho VO. Effect of combined aerobic and resistance training on peak oxygen consumption, muscle strength and health-related quality of life in patients with heart failure with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Cardiology. 2019 Jun 24.

- ↑ Maldonado-Martín S, Brubaker PH, Ozemek C, Jayo-Montoya JA, Becton JT, Kitzman DW. Impact of β-Blockers on Heart Rate and Oxygen Uptake During Exercise and Recovery in Older Patients With Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2020 Jan 2.

- ↑ Lan NS, Lam K, Naylor LH, Green DJ, Minaee NS, Dias P, Maiorana AJ. The Impact of Distinct Exercise Training Modalities on Echocardiographic Measurements in Patients with Heart Failure with Reduced Ejection Fraction. Journal of the American Society of Echocardiography. 2019 Dec 4.

- ↑ MEDICA EM. Group-based cardiac rehabilitation interventions. A challenge for physical and rehabilitation medicine physicians: a randomized controlled trial. European Journal of Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine. 2020 Jan 23.

- ↑ Paul J Beckers, Andreas B Gevaert High intensity interval training for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: High hopes for intense exercise European Journal of Preventive Cardiology 0(00) 1–3 The European S Article reuse guidelines: sagepub.com/journals-permissions DOI: 10.1177/2047487320910294 journals.sagepub.com/home/cpr

- ↑ Hamazaki N, Kamiya K, Yamamoto S, Nozaki K, Ichikawa T, Matsuzawa R, Tanaka S, Nakamura T, Yamashita M, Maekawa E, Meguro K. Changes in Respiratory Muscle Strength Following Cardiac Rehabilitation for Prognosis in Patients with Heart Failure. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020 Apr;9(4):952.

- ↑ Juárez-Vela R, Durante Á, Pellicer-García B, Cardoso-Muñoz A, Criado-Gutiérrez JM, Antón-Solanas I, Gea-Caballero V. Care Dependency in Patients with Heart Failure: A Cross-Sectional Study in Spain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020 Jan;17(19):7042.