Activities for Training Infant Sitting

Development of Sitting[edit | edit source]

The developmental trajectory for sitting can be described in 3 overlapping stages:

- Sitting with support on a caregiver’s lap.

- Sitting on a flat surface with external support and arm propping

- Independent sitting and transitions to prone lying and kneeling

Identifying the segmental level of control[edit | edit source]

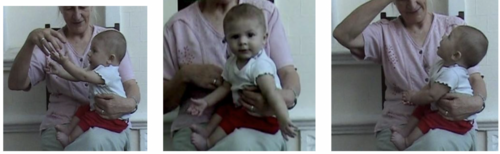

A good place to start figuring out the level of support an infant needs to maintain the trunk and head erect and steady, is to observe the infant sitting on the carer's lap.

First observe how and where the carer provides manual support, as well as the infant's postural response to this support.

Often a small adjustment of the carer’s support makes a big different to the infant’s ability to keep the head and trunk erect.[1][2]

Support can be provided at the level of the axilla, lower thorax, waist and pelvis.

You can also check the level of manual support the infant needs when supported in sitting on a flat surface.

Here you see manual support provided at the level of the axilla, waist and the pelvis.

Adapting the environment to challenge sitting abilities[edit | edit source]

Once the level of manual support that is needed to allow the infant to sit erect with relative ease, the next step is to explore ways to adapt the environment to encourage visual reaching and exploration, social engagement and reaching in different directions. These activities challenge the infant’s postural and balance responses.

When the carer's manual support is not effective[edit | edit source]

If the infant is not being supported in a way that allows them keep the upper trunk and head erect and steady with relative ease, show the carer how to change her manual support in a way that provides more effective support.If the infant is not able to hold the head erect, even with axilla level support, the first step is to adjust the position of the manual support to make keeping the head erect easier and possible.

Let the carer lean back a little so that the infants' head can rest against their chest. Encourage the carer to adjust their manual support so that the infant can keep the head steady but still needs to put some effort into maintaining the position.

Providing an infant with something to look at will usually stimulate the infant to put effort into stabilizing the head.

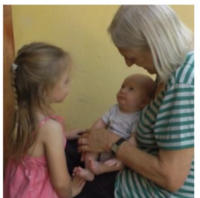

Engagement with a social partner who has an animated face and voice is often a powerful way captivate the infant’s attention and increase their effortful control.[3][4]

Lap sitting when the carer provides effective support[edit | edit source]

If the support provided by the carer allows the infant to sit erect, hold the head up and look around, your next step is to encourage the infant to reach for, and grasp, a toy or a moving hand. Remember to allow time for the infant to respond.

Choose toys that are easy to grasp. Use bright toys that make a gentle noise to get the infant’s attention.

It is also useful to suggest to the carer ways to move their hands, so that they are providing less support than usual, and in this way challenge the infant’s abilities to steady the head.

Providing less support when lap sitting, and as part of everyday handling and social interactions, also provides infants with an opportunity to practice maintaining a steady head and trunk in different situations.[3][4]

Sitting on a firm flat surface with block support[edit | edit source]

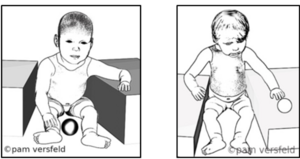

Once an infant can maintain the head and trunk erect when sitting with manual support around the waist or pelvis, it is time to explore their ability to sit erect on a flat surface using external support provided by 10-15 cm high firm flat sofa cushions, foam blocks or boxes

Here you see Lily sitting between 2 firm foam blocks 10 cm high.

A foam block or firm sofa cushion is positioned on either side of the child, with the block in contact with the buttocks and lateral aspect of the thighs and chest.

Another block is positioned behind the child.

The raised surface on either side makes it easier for the child to use the hands to prop on, which helps keep the trunk erect and also increases the base of support (BOS) in a lateral direction.

The next step, is to encourage the child to reach for toys, that are placed either, on the support surface between the child’s legs, or on the raised surface provided by the blocks.

Children will quite quickly learn to reach forwards and come up erect again, sometimes using one hand to prop on the raised surface.

Reaching to the side for toys within easy reach[edit | edit source]

Once the child can maintain sitting erect with lateral block support, the next step is to encourage reaching with one hand to toys placed within easy reach, alternating between the left and right side.

As the child’s sitting stability and balance improves the toys are placed a little further away, sometimes further forwards and sometime a further back requiring some trunk rotation.

Remember that reaching further than arm’s length is achieved by a coordinated action between the trunk leaning in the direction of the intended reach, and lifting and extending the arm.

This coordinated trunk-arm action is learned through repeatedly exploring different ways of getting the hand to the toy, and may involve many failed attempts and falls. [5][6]

Falling is an important part of learning to balance in sitting[edit | edit source]

Falling happens, when a child explores different strategies for extending their reach and in so doing sometimes moves the center of pressure too close to the edge of the base of support.

Typically developing infants do not seem to be to hassled by falling, and, if they have effective head righting responses mostly do not bang their heads.

Reducing the amount of external support[edit | edit source]

Sitting with block support is progressed by moving the blocks a small distance away from the pelvis and thighs. In this position the external support provided to the pelvis, is removed.

The child now has to learn to maintain balance without external support, which may lead to an increase in falls to the side. However, the presence of the raised surface means that the distance of the fall is small and makes it easier for the child to push up on the arms.[7][8]

Learning to sit without support[edit | edit source]

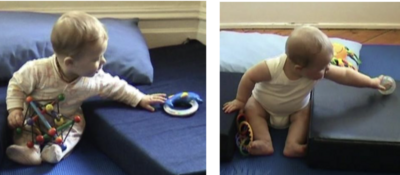

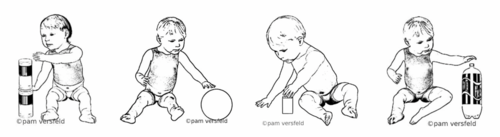

Once the infant is able to sit without any external support the next step is to provide many opportunities to sit and play with a range of toys and other interesting objects of different shapes, sizes and weights.

Start by placing toys in different positions but still within easy reach.

Picking up, moving and manipulating toys challenges the child’s ability to activate anticipatory and compensatory postural responses to maintain a steady upright position and maintain balance.[9][10]

As the child’s ability to reach for objects within easy reach improves, move the toys a little further away so that the child needs to combine trunk leaning or rotation with and shoulder flexion to make contact with the toy.

Because backwards falls are still common, putting a pillow behind the child is a good ideas so that is the child does fall they do not bang their head.

Moving from sitting to prone kneeling[edit | edit source]

Infants move from sitting to kneeling in one of two ways.

Reaching far forwards and taking weight on the hands.

In this sequence of movements moving the weight from the buttocks onto the hands and knees requires the momentum produced by a rapid forwards movement of the trunk.

Rotation of the trunk and reaching across the body is another pattern of movement used for transitioning from sitting to prone kneeling.

Importance of motivation to move and play with toys[edit | edit source]

An infant’s interest in interacting with toys and other interesting objects provides the impetus for learning to balance in sitting. Reaching actions create perturbing forces that are counteracted by anticipatory and compensatory postural responses that are important for maintaining balance. [11][12] So one of the challenges in training sitting is finding what motivates a child to move in ways that challenges their abilities and encourages them to persistent until they achieve their goals.

To summarize[edit | edit source]

Training sitting is starts with identifying the amount and type of support the infant needs to maintain an erect and stable sitting posture.

Once this is known, the next step is to provide opportunities for practicing sitting with the necessary support by encouraging the infant to look around and reach for toys first within easy reach, and then placing the toys out of reach to challenge the infant’s postural responses.

And when the infant has learned to sit without support, placing toys progressively further away will encourage shifting around on the floor and transitions to prone lying and kneeling.

Resources[edit | edit source]

- Development of Sitting

- Newborn Perceptual Motor Behaviour

- Family Centred Early Intervention and Diagnosis

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Sangkarit N, Siritaratiwat W, Bennett S, Tapanya W. Factors Associating with the Segmental Postural Control during Sitting in Moderate-to-Late Preterm Infants via Longitudinal Study. Children. 2021 Sep 26;8(10):851.

- ↑ Pin TW, Butler PB, Cheung HM, Shum SL. Relationship between segmental trunk control and gross motor development in typically developing infants aged from 4 to 12 months: a pilot study. BMC pediatrics. 2019 Dec;19(1):1-9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Kretch KS, Koziol NA, Marcinowski EC, Kane AE, Inamdar K, Brown ED, Bovaird JA, Harbourne RT, Hsu LY, Lobo MA, Dusing SC. Infant posture and caregiver‐provided cognitive opportunities in typically developing infants and infants with motor delay. Developmental Psychobiology. 2022 Jan;64(1):e22233.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Franchak JM. Changing opportunities for learning in everyday life: Infant body position over the first year. Infancy. 2019 Mar;24(2):187-209.

- ↑ Mlincek MM, Roemer EJ, Kraemer C, Iverson JM. Posture Matters: Object Manipulation During the Transition to Arms-Free Sitting in Infants at Elevated vs. Typical Likelihood for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Physical & Occupational Therapy In Pediatrics. 2022 Jan 9:1-5.

- ↑ Corbetta D. Perception, action, and intrinsic motivation in infants’ motor-skill development. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2021 Oct;30(5):418-24.

- ↑ Soska KC, Adolph KE. Postural position constrains multimodal object exploration in infants. Infancy. 2014 Mar;19(2):138-61.

- ↑ Rachwani J, Santamaria V, Saavedra SL, Woollacott MH. The development of trunk control and its relation to reaching in infancy: a longitudinal study. Frontiers in human neuroscience. 2015 Feb 24;9:94.

- ↑ Kyvelidou A, Stuberg WA, Harbourne RT, Deffeyes JE, Blanke D, Stergiou N. Development of upper body coordination during sitting in typically developing infants. Pediatric research. 2009 May;65(5):553-8.

- ↑ Maki BE, McIlroy WE. The role of limb movements in maintaining upright stance: the “change-in-support” strategy. Physical therapy. 1997 May 1;77(5):488-507.

- ↑ Atun-Einy O, Berger SE, Scher A. Assessing motivation to move and its relationship to motor development in infancy. Infant Behavior and Development. 2013 Jun 1;36(3):457-69.

- ↑ Rachwani J, Soska KC, Adolph KE. Behavioral flexibility in learning to sit. Developmental psychobiology. 2017 Dec;59(8):937-48.