Gluteus Medius

Original Editor - Alex Palmer,

Top Contributors - Alex Palmer, George Prudden, Kim Jackson, Ahmed Nasr, Joao Costa, Joanne Garvey, Candace Goh, Nupur Smit Shah, WikiSysop, Kai A. Sigel, Vidya Acharya, Pinar Kisacik, Rachael Lowe and Evan Thomas;

Description[edit | edit source]

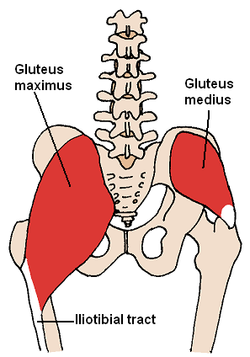

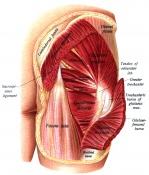

Gluteus medius is located on lateral aspect of the upper buttock, below the iliac crest. The superior muscle is broad with the muscle narrowing towards its insertional tendon giving it a fan-shape. Guteus maximus overlaps the muscle posteriorly. Gluteus medius is an important muscle in walking, running and single leg weight-bearing.[1] Weakness in this muscle has been associated with lower-limb musculoskeletal pathology[2] and gait disturbance following stroke.[3]

Origin[edit | edit source]

Gluteal, or lateral surface of the ilium between the posterior and anterior gluteal lines. This is a large area, reaching from the iliac crest above to the almost the sciatic notch below.[1]

Insertion[edit | edit source]

Posterior fibres pass forwards and downwards, the middle fibres downwards, anterior fibres pass backwards and downwards. Fibres combine to form a flatterned tendon which attaches to the superlateral side of the greater trochanter of the femur.[1]

Nerve supply[edit | edit source]

The gluteus medius is supplied by the superior gluteal nerve (root L4, 5 and S1). Cutaneous supply is mainly provided by L1 and 2.[1]

Function[edit | edit source]

Gluteus medius acts to abduct and medially rotate the hip.

Maintaining single-leg stance is required during walking and running. When a limb is taken off the ground the pelvis on the opposite side will tend to drop through loss of support from below. Gluteus medius works to maintain the side of the pelvis that drops therefore allowing the other limb to swing forward for the next step.

Gluteus medius also supports the pelvis during gait by producing rotation of hip with assitance from gluteus minimus and tensor fascia lata. Conversely, the hip is supported during the stance phase by acting on on the same side.

The Trendelenburg sign is when the muscle is unable to work efficently due to pain, poor mechanics or weakness, the pelvis will drop on the opposite side to the weakness. A trunk compensation is often observed with a Trendelenburg gait.[1]

Anatomy Overview[edit | edit source]

Assessment[edit | edit source]

Palpation[edit | edit source]

Find the middle of iliac crest which is located above the greater trochanter.Two fingers below is the bulk of gluteus medius. The contraction of the muscle can be felt by alternate single leg stands.[1]

Power[edit | edit source]

- Hip abduction in side-lying

- Double or single-leg stance test

- Adding an upper body movement to the single-leg stance test

- Assessment of functional tasks that require single-leg stance such as step-downs, walking or running.[4]

Length[edit | edit source]

Treatment[edit | edit source]

Pressman and colleagues describe a progressive program for strengthening gluteus medius weakness.[4]

- Nonweightbearing and basic weightbearing exercises such as clam shell exercises, sidelying hip abduction, standing hip abduction, and basic single leg balance exercises. Progress when the patient can hold their pelvis level during single leg stance for 30 seconds.

- Weight-bearing exercises and gradually progresses stability exercises by (i) translating the center of gravity horizontally via stepping and/or hopping exercises; (ii) reducing the width of the base of support, (iii) increasing the height of the center of gravity by elevating the arms and/or hand-held weights, or (iii) performing the exercises on unstable surfaces.

- Sport-specific movement patterns.

Resources[edit | edit source]

|

|

|

|

|

See also[edit | edit source]

Greater trochanteric pain syndrone

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Palastanga N, Soames R. Anatomy and Human Movement: Structure and Function. 6th ed. London, United Kingdom: Churchill Livingstone; 2012.

- ↑ Barton CJ, Lack S, Malliaras P, Morrissey D. Gluteal muscle activity and patellofemoral pain syndrome: a systematic review. British journal of sports medicine. 2012 Sep 3:bjsports-2012.

- ↑ Buurke JH, Nene AV, Kwakkel G, Erren-Wolters V, IJzerman MJ, Hermens HJ. Recovery of gait after stroke: what changes?. Neurorehabilitation and Neural Repair. 2008 Nov 1;22(6):676-83.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Presswood L, Cronin J, Keogh J, Whatman C (2008). Gluteus Medius: Applied Anatomy, Dysfunction, Assessment, and Progressive Strengthening. Strength and Conditioning Journal, 30 (5), 41-53

- ↑ Physiotutors. Top 5 Gluteus Medius Exercises. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=GwPe0JwYbrA