The Calgary-Cambridge Guide to the Medical Interview - Gathering Information on the Biomedical History

What is meant by gathering information?[edit | edit source]

The history-taking or information-gathering session form an essential skill of the healthcare practise that assists in the diagnosis of the patient's physical problems. The success of such a process relies on many factors including; preparation, planning, and communication between the healthcare professional and the patient[1]. During the consultation, the physiotherapist or other healthcare practitioner aims to gather the information they need to interpret and understand the nature of the symptoms and how patients are coping with them[2]. Accurate information accounts for 80% of what is needed to diagnose a condition [3]

| ''Taking a patient history is like playing detective, ‘searching for clues, collecting information without bias, yet staying on track to solve the puzzle[2]’'' |

|---|

Active listening is considered to be the most fundamental communication skill required for a successful consultation which involves verbal and non-verbal behaviours. The non-verbal behaviours are summarized in the SOLER framework: sitting Square on to the patient with an Open position. Leaning slightly forward, making Eye contact with a Relaxed posture.

The verbal elements of active listening are appropriate questioning techniques and summarising and recalling the history back to the patient[2]

Ask your patient active questions to encourage them to give you more about their condition and avoid closed questions that are answered with 'yes' or 'no'.

Summarising or recalling history is a dynamic process in which the patient has the opportunity to clarify, add, or correct the information[4].

To avoid side-tracking, it's recommended to use a history taking framework that could help you to structure your history taking process and go through the important questions in an orderly and organized way.

Dynamic clinical reasoning is necessary to develop relevant hypotheses, Following that, it is recommended to follow a function-based approach in the investigation, select the appropriate assessment techniques, formulate a sound diagnosis and ensure a comprehensive and applicable management plan[5].

Clinical reasoning and Hypothesis Generation[edit | edit source]

Clinical reasoning is defined as a process of analyzing acquired clinical data in combination with patient preferences, professional judgment, and scientific knowledge, with the goal of structuring meaning, developing objectives, and implementing health management strategies in the management of a patient[6].

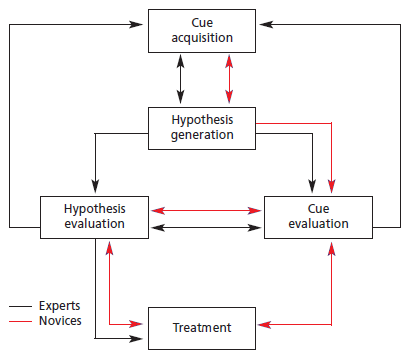

A sound hypothesis depends on good quality clinical reasoning, using as much as possible clinically relevant information gained during the patient interview[5]. Physiotherapists often apply clinical reasoning to arrive at a working hypothesis by utilizing either a hypothetico-deductive model, or pattern recognition, or a combination of the two.

In a hypothetico-deductive model, hypotheses are generated from all observations, after which clinical data gained is tested to arrive at the most likely hypothesis. Pattern recognition is generally used by more experienced physiotherapists. It refers to the formation of a hypothesis from typical symptom and disease presentation noted, and subsequent data exploration to confirm or negate the hypotheses[6].

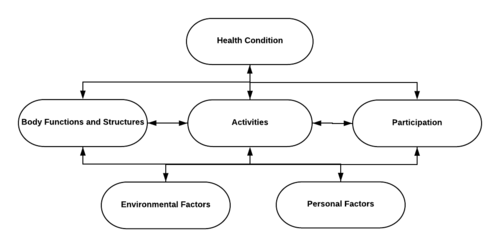

The use of the International Classification of Function and Disability and Health model (ICF) can help the physiotherapist to better understand the context of the presenting patient during the process of clinical reasoning and hypothesis generation. It aids to organize information in a practical and logical manner, while also integrating environmental, social, and psychological factors in the understanding of the person and condition[6]. Furthermore, the use of the ICF as an outcome measure allows to standardise patient impairment and provides a concrete, comparable benchmark by which to measure the effect of management.

The International Classification of Function, Disability and Health (ICF)[edit | edit source]

The ICF is a classification system that describes the different components of the functioning of a person with any health condition. Approved by the World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2001, the ICF was accepted as a universal conceptual model and taxonomy of human functioning[5].

The ICF describes human functioning as an interaction between body functions and structures, activities, and participation, together with the effect of psychological and environmental influences. The model is built on biopsychosocial principles which regard the patient as a holistic, psychological being within a specific environment. Disability is described according to impairment of body functions/structure, limitations in activities, and restrictions in participation[7].

Body functioning and structures refer to physiological processes and anatomic structures, and any abnormality to these is referred to as an impairment.

Activity refers to the execution of tasks or actions and represents the individual’s perception of function. The inability to perform normal activities is referred to as limitations.

Participation refers to life situations in which an individual is actively involved. The inability to engage in normal participation is called participation restrictions.

Environmental and personal factors are collectively known as contextual factors and refer to the influence of surroundings, psychology, and experience of illness on the patient’s health[8].

From a biopsychosocial point of view, the ICF is a model for standardisation of function and health which allows for comparison across the spectrum of disability. The inclusion of contextual factors provides a patient-specific representation of function which illustrates why different individuals may be differently affected by a seemingly similar pathology. For example, one patient may walk on a fractured metatarsal for days before having it diagnosed, where another patient with similar biomedical factors and who sustained a similar injury may be in much more distress soon after the onset of the injury. Differences in contextual factors may also influence the recovery and behaviour of the individual[8].

Many conditions are chronic and progressive in nature and that some patients will never be completely asymptomatic such as Parkinson’s disease or cystic fibrosis. Therefore, the aim of rehabilitation should be helping those patients to reach their optimal physical, psychological, social, occupational, and educational potential within the anatomical and physiological capacity available[9]. The ICF aids rehabilitation professionals to gauge the functional capacity of a patient, analyse the source of restrictions and limitations, and compile a realistic management plan accordingly[5].

Knowledge of a patient’s functional impairment will furthermore assist the physiotherapist to select assessment techniques based on symptom-eliciting functional movements. For this reason, it is strongly recommended that the process of information gathering should be based on the patient’s current functional capacity and the potential effect of the presenting condition/symptoms[10].

What information should we gather when assessing our patients?[edit | edit source]

The process of investigating biomedical history is highly dependent upon the subspecialty of medicine/allied health involved[11], however, the basic principles remain the same across the spectrum.

Red flags[edit | edit source]

Red flags are any signs or symptoms that may indicate a possibly serious underlying condition, that warrants further medical assessment and/or intervention[12] before continuing with the therapeutic management.

When screening for red flags, is it recommended to explain to the patient why you are asking those questions to ensure ruling out serious conditions while confirming that their prevalence is mostly low to avoid distressing your patient. If you identify a red flag, share your findings with your patient, and explain it in a logical manner and a simple language that the patient can easily understand and possibly refer to the relevant speciality[5].

Presenting symptoms[edit | edit source]

A good place to start from when taking history is to explore what is the most concerning problem of the patient.

A patient-centred approach investigates the patients’ ideas and concerns about their symptoms and their expectations[4]. The majority of patients will not show how anxious they are about their condition thus it's important to ask about what they think regarding their symptoms to get an understanding of their worries and include that in the discussion.

The mnemonic PQRST[13] is a framework developed to be used in information gathering:

- Palliation/provocation refers to any factors that may exacerbate/aggravate or improve symptoms. It can provide valuable information on the nature and causes of the symptoms. It could be specific movements, emotional state, or overload that contribute to the symptoms[14][10].

- Quality of symptoms: also refers to the type or nature of symptoms. this involves the patient's perception of the presenting symptoms which could give clues on the aetiology of the condition[2]. Example of questions: “what type of pain is it?” or “Is it a sharp pain, or burning? Or a dull ache?” or “Would you say your cough is dry or wet? Maybe wheezy, or barking?”)[5]

- Region/Radiation a body chart aids to conceptualise symptoms and assists the physiotherapist to recognize potential patterns that may be specific to certain conditions.

- Severity: different scales and outcome measures could be used such as the VAS, the Disability of Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire, or the Dizziness Handicap Inventory (DHI).

- Timing: refers to 1- a timeline from onset to the current presentation, including further exploration of mechanisms, and any regression/progression of the condition since onset. 2- Any 24-hour pattern, for example, worse at night, or stiffness and pain first thing in the morning. 3- frequency of symptoms i.e. intermittent or constant.

Current Medical History[edit | edit source]

Asking questions in regards with:

- The prevalence of chronic conditions

- Medications: consider the duration of use of medications and their side effects

- General health including habits such as smoking, alcohol, drug use, diet, sleep, exercises, activities, and preventive health measures such as screening and immunization

It's important here to remain objective, sensitive, and respectful at all times as patients often feel ashamed or stigmatized for certain conditions or medicinal uses. Create a safe, non-judgmental space when assessing these, since patients are often reluctant to share this type of information with health-care professionals[5].

Previous medical history[edit | edit source]

Although might seem irrelevant, physical trauma, hospitalization, or injuries throughout the patient’s lifetime should be enquired[5].

Family history[edit | edit source]

To exclude the possibility of any link to genetic or hereditary diseases, the family history of the previous two generations should be visited during the information gathering process. Counselling on preventative screening should be advised when hereditary disease is found[2].

Review of the systems[edit | edit source]

In an ideal world, a complete head-to-toe checkup gives a comprehensive image of the patient's condition, however, this process wouldn't be appropriate for most clinical settings with limited time. A decision is made based on good judgment and clinical reasoning on which system review to include in the assessment.

This table provides a summary of additional somatic systems to consider in the assessment. It is important to explain to the patients why other systems are investigated to prevent unnecessary anxiety[2].

| SYSTEM | FACTORS TO CONSIDER |

|---|---|

| Head | Dizziness, headaches, faintness, recent head injury |

| Eyes | Any changes in vision, regular optometric tests |

| Respiratory | Breathing problems, coughing, wheezing, sputum production, allergic rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, earache hearing loss |

| Cardiac | Anemia, hypertension, palpitations |

| Gastrointestinal | Heartburn, irritable bowel syndrome, nausea, changes in regular toileting routine |

| Urogenital/gynaecological | Pain with urination, menstruation-related symptoms, changes in regular toileting routine |

| Muskuloskeletal | Stiffness, cramps, weakness, swelling |

| Neurological | Numbness, tingling, tremors, weakness, coordination, balance |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Gask L, Usherwood T. The consultation. Bmj. 2002 Jun 29;324(7353):1567-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Kaufman G. Patient assessment: effective consultation and history taking. Nursing Standard. 2008 Oct 1;23(4).

- ↑ Epstein O, Perkin GD, Cookson J, Watt IS, Rakhit R, Robins AW, Hornett GA. Clinical Examination E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2008 Jul 7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Moulton L. The naked consultation: A practical guide to primary care consultation skills. CRC Press; 2017 Jul 14.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 Fourie M. Gathering Information - Underpinning Biomedical History. Phsyioplus Course 2020

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Jones M, Edwards I, Gifford L. Conceptual models for implementing biopsychosocial theory in clinical practice. Manual therapy. 2002 Feb 1;7(1):2-9.

- ↑ Stucki G, Cieza A, Melvin J. The international classification of functioning, disability and health: A unifying model for the conceptual description of the rehabilitation strategy. Journal of rehabilitation medicine. 2007 May 5;39(4):279-85.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Johnston M, Dixon D. Developing an integrated biomedical and behavioural theory of functioning and disability: adding models of behaviour to the ICF framework. Health psychology review. 2014 Oct 2;8(4):381-403.

- ↑ Heerkens Y, Hendriks E, Oostendorp R. Assessment instruments and the ICF in rehabilitation and physiotherapy. Medical Rehabilitation. 2006;10(3):1-4.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Fava GA, McEwen BS, Guidi J, Gostoli S, Offidani E, Sonino N. Clinical characterization of allostatic overload. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2019 Oct 1;108:94-101.

- ↑ Johnson P. Assessment and clinical reasoning in the Bobath concept. Bobath Concept. 2009 Jul 3:43.

- ↑ Briggs AM, Fary RE, Slater H, Ranelli S, Chan M. Physiotherapy co-management of rheumatoid arthritis: Identification of red flags, significance to clinical practice and management pathways. Manual therapy. 2013 Dec 1;18(6):583-7.

- ↑ Estes ME. Health assessment and physical examination. Cengage Learning; 2013 Feb 25.

- ↑ Butler RK, Finn DP. Stress-induced analgesia. Progress in neurobiology. 2009 Jul 1;88(3):184-202.