Free Radicals

Original Editor - Lucinda hampton

Top Contributors - Lucinda hampton

Introduction[edit | edit source]

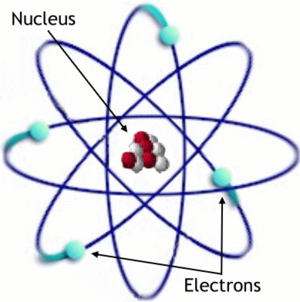

Free radicals are unstable atoms that can damage cells, causing illness and aging.

- Atoms are surrounded by electrons that orbit the atom in layers called shells. Each shell needs to be filled by a set number of electrons. When a shell is full; electrons begin filling the next shell.

- If an atom has an outer shell that is not full, it may bond with another atom, using the electrons to complete its outer shell. These types of atoms are known as free radicals[1].

The reactivity of free radicals is what poses a threat to macromolecules such as DNA, RNA, proteins, and fatty acids. Free radicals can cause chain reactions that ultimately damage cells. eg

- A superoxide molecule may react with a fatty acid and steal one of its electrons. The fatty acid then becomes a free radical that can react with another fatty acid nearby. As this chain reaction continues, the permeability and fluidity of cell membranes changes, proteins in cell membranes experience decreased activity, and receptor proteins undergo changes in structure that either alter or stop their function. If receptor proteins designed to react to insulin levels undergo a structural change it can negatively effect glucose uptake.

Free radical reactions can continue unchecked unless stopped by a defense mechanism[2].

The Body’s Defense[edit | edit source]

Free radical development is unavoidable, but human bodies have adapted by setting up and maintaining defense mechanisms that reduce their impact. The body’s two major defense systems are free radical detoxifying enzymes and antioxidant chemicals.

- Free radical detoxifying enzyme systems are responsible for protecting the insides of cells from free radical damage.

- An antioxidant is any molecule that can block free radicals from stealing electrons; antioxidants act both inside and outside of cells[2].

The Body’s Offense[edit | edit source]

While our bodies have acquired multiple defenses against free radicals, we also use free radicals to support its functions. eg.

- The immune system uses the cell-damaging properties of free radicals to kill pathogens. First, immune cells engulf an invader (such as a bacterium), then they expose it to free radicals such as hydrogen peroxide, which destroys its membrane. The invader is thus neutralized.

- Scientific studies also suggest hydrogen peroxide acts as a signaling molecule that calls immune cells to injury sites, meaning free radicals may aid with tissue repair when you get cut.

- Free radicals are necessary for many other bodily functions as well. The thyroid gland synthesizes its own hydrogen peroxide, which is required for the production of thyroid hormone. Reactive oxygen species and reactive nitrogen species, which are free radicals containing nitrogen, have been found to interact with proteins in cells to produce signaling molecules. The free radical nitric oxide has been found to help dilate blood vessels and act as a chemical messenger in the brain.

- By acting as signaling molecules, free radicals are involved in the control of their own synthesis, stress responses, regulation of cell growth and death, and metabolism.[2]

Theory of Aging[edit | edit source]

The free radical theory of Aging, one of the nine suggested hallmarks of aging, implicates the gradual accumulation of oxidative cellular damage as a fundamental driver of cellular aging. This theory has evolved over time to emphasize the role of free radical induced mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) mutations and the accumulation of mtDNA deletions. Given the proximity of mtDNA to the electron transport chain, a primary producer of free radicals, it postulates that the mutations would promote mitochondrial dysfunction and concomitantly increase free radical production in a positive feedback loop. The observation of oxidative damage in the form of 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-deoxyguanosine (8-oxodG) DNA oxidative lesions accumulating with age has been a cornerstone of the free radical theory of aging.

- Based on recent findings, an updated understanding regarding the role of free radicals in contemporary theories of mtDNA aging is needed. It seems likely that rather than directly contributing to mtDNA mutations via oxidative lesions, free radicals may affect the mitochondrial polymerase and decrease its fidelity, indirectly increasing somatic transition mutations.[3]

Image: Free Radicals Damage Mitochondria, which according to the mitochondrial free radical theory of ageing, leads to ageing.

Antioxidants vs Free Radicals[edit | edit source]

Antioxidants are a commonly promoted feature of health foods and supplements. They’re portrayed as the good forces that fight free radicals preventing damage thought to hasten ageing and cause chronic diseases.

The simple logic that antioxidants are “good” and free radicals are “bad”, has led to the idea that simply getting more antioxidants into our bodies, from foods or supplements, can outweigh the impacts of free radicals. Sadly, biology is never this simple, and antioxidants are not a free radical free pass.

We are exposed to free radicals every day; they’re produced in our bodies as part of normal functioning. Such normal levels are easily tolerated.

Increase risk of free radical damage occurs with eg habits such as smoking, alcohol, and eating processed foods. These additional free radicals may increase the risk of lifestyle and age-related diseases eg cancer and cardiovascular disease.

- Antioxidants can react with free radicals without getting damaged or becoming a free radical themselves and stop the chain reaction.

- There are hundreds of substances that can act as antioxidants. Well-known antioxidants include vitamin C and vitamin E, both of which are found in fruits and vegetables.

- A diet including sources of antioxidants is necessary for good health (studies have shown that cancer rates are lower in people with diets rich in fruits and vegetables).

- The benefits of supplementing diets with additional antioxidants are lacking. In fact, some studies have shown that taking antioxidant supplements can sometimes increase the risk of cancer.

- Despite these uncertainties about their efficacy, supplemental antioxidants are a boom industry, sold as a health panacea and added to a range of processed foods, including juices, cereals, chocolate bars, and alcoholic beverages.[4]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Medical news Today Free Radicals Available from: https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/318652#What-are-free-radicals (accessed 6.3.2021)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Libretext Free radicals Available from: https://med.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Nutrition/Book%3A_An_Introduction_to_Nutrition_(Zimmerman)/08%3A_Nutrients_Important_as_Antioxidants/8.02%3A_Generation_of_Free_Radicals_in_the_Body(accessed 6.3.2021)

- ↑ Ziada AS, Smith MS, Côté HC. Updating the Free Radical Theory of Aging. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology. 2020;8.Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7525146/accessed 7.3.2021)

- ↑ The Conversation Health Check: the untrue story of antioxidants vs free radicals Available from:https://theconversation.com/health-check-the-untrue-story-of-antioxidants-vs-free-radicals-15920 (accessed 7.3.2021)