Fibular Fracture

Original Editor - The Open Physio project.

Top Contributors - Ilona Malkauskaite, Angeliki Chorti, Admin, Rachael Lowe, Kim Jackson, Oyemi Sillo, WikiSysop, Karen Wilson, Claire Knott and Lucinda hampton

Description[edit | edit source]

Fractures of the tibia and fibula most common in athletes, especially runners or non-athletes who suddenly increase their activity level. Many factors appear to contribute to the development of these fractures including changes in athletic training, specific anatomic features, decreased bone density, and diseases.[1] Fractures of the fibula sometimes occur with severe ankle sprains. It can happen anywhere along the fibula. The fibula only bears 17% of the body weight so these fractures are not as severe as weight bearing bone fractures.[2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

The fibula is a non-weight bearing bone that originates just below the lateral tibial plateau and extends distally to form the lateral malleolus, which is the portion of the fibula distal to the superior articular surface of the talus. The lateral malleolus provides key stability against excessive eversion of the ankle and foot. Proximally, the fibular head is the site of attachment of the lateral collateral ligament of the knee and of the tendon from the biceps femoris. Just below the fibular head the common peroneal nerve wraps around the fibular neck before dividing at the proximal fibula into deep and superficial branches.[1] Along the upper and middle lateral border of the fibula, the Peroneal (Fibularis)Longus and brevis muscles originate and provide some soft tissue protection to the fibula from direct contusion.[3] The fibrous attachment between the tibia and fibula, the tibiofibular syndesmosis, prevents displacement of the lateral malleolus. The distal portion of the syndesmosis has thickened fibers to form the distal tibio-fibular ligament. Stability of this ligament allows the ankle to remain stable with external rotation and during the forceful cutting movements required in many sports. Disruption of the syndesmosis (syndesmotic or high ankle sprain) contributes to instability of the tibiotalar joint.[1]

Mechanism of Injury / Pathological Process[edit | edit source]

Mechanisms of injury for tibia-fibula fractures can be divided into 2 categories:

- low-energy injuries such as ground levels falls and athletic injuries

- high-energy injuries such as motor vehicle injuries, pedestrians struck by motor vehicles, and gunshot wounds.

Patients may report a history of direct (motor vehicle crash or axial loading) or indirect (twisting) trauma and may complain of pain, swelling, and inability to ambulate with tibia fracture. [4]

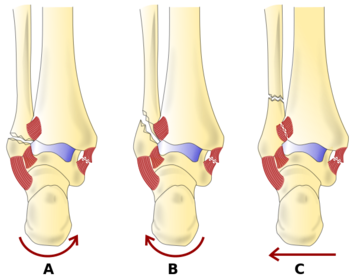

Ankle fractures are classified according to Danis -Weber classification.

The Danis-Weber classification[5]

Type A is a transverse fibular fracture caused by adduction and internal rotation.

Type B, is caused by external rotation, it is shown as a short oblique fibular fracture directed mediolaterally upward from the tibial plafond.

There are two type C fractures: type C 1 is an oblique medial-to-lateral fibular fracture which is caused by abduction.

type C 2 fractures result from a combination of abduction and external rotation, producing more extensive syndesmotic injury and a higher fibular fracture.

In more simple terms Danis-Weber Classification:

The Danis-Weber classification system uses the position of the level of the fibular fracture in its relationship to its height at the ankle joint.

Type A: fracture below the ankle joint

Type B: fracture at the level of the joint, with the tibiofibular ligaments usually intact.

Type C: fracture above the joint level which tears the syndesmotic ligaments.

Epidemiology/Etiology[edit | edit source]

Fibular fractures in adults are often caused by trauma. Isolated fibular fractures contain the majority of ankle fractures in older women, occurring in approximately 1 to 2 of every 1000 white women each year.[6] Fibular fractures may also occur as the result of repetitive loading and in this case they are referred to as stress fractures.

Risk factors[edit | edit source]

Bone mass is the key risk factor for fractures of the fibular or tibial shaft in older adults. Factors that reduce bone mass had greater impact than overall health status or other risk factors for falling. [7] Cigarette smoking is another important risk factor for fibular fractures.[8]

Fibular fractures are more common among athletes engaged in sports that involve cutting, particularly those associated with contact or collision, for example American football, soccer and rugby [9]. Participants in downhill winter sports have relatively high rates of fibular fractures. These are more common in snowboarding than skiing, and fracture patterns are different for each. Skiers often fracture the proximal third of the tibia and also the fibula, whereas snowboarders are more likely to sustain isolated fractures of the distal third of the fibula [10].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

A fractured fibula includes those signs and symptoms:

- Pain, swelling and tenderness;

- Inability to bear weight on the injured leg;

- Bleeding and bruising in the leg;

- Visible deformity;

- Numbness and coldness in the foot

- Tender to the touch.[11]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

- Physical examination: A thorough examination will be conducted for any noticeable deformities.

- X-Rays are used to see the fracture and see if a bone has been displaced.

- MRI Scans provides a more detailed scan and can generate detailed pictures of the interior bones and soft tissues

Bone scans, CT Scans, and other tests may be ordered to make a more precise diagnosis and judge the severity of the fibula fracture.[11]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Acute Compartment Syndrome

- Tibia Fracture

- Ankle Fracture

- Ankle Injury, Soft Tissue

- Child Abuse

- Knee Fracture

- Pediatric Limp

- Peripheral Vascular Injuries

- Soft Tissue Knee Injury [12]

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

Ankle fractures will predominantly require surgical fixation, however if deemed intrinsically stable may be treated conservatively. If the fracture is open, additional management is warranted to reduce the risk of contamination and infection. [13]

Physical therapy management[edit | edit source]

After being in a cast or splint for several weeks, most people find that their leg is weak and their joints stiff. Physical therapy is implemented after an individual assessment of the patient. It is important to assess these measurements:

- Range of motion

- Strength

- Surgical scar tissue assessment

- How the patient walks and bears weight

- Pain

Physical therapy usually begins with ankle strengthening and mobility exercises. Once the patient is strong enough to put weight on the injured area, walking and stepping exercises are common. Balance is a vital part of regaining the ability to walk unassisted. Wobble board exercises are a great way to work on balance.[11]

According to ORIF fibula fracture post-operative protocol there are 4 phases in rehabilitation of fibular fracture: [14]

Phase 1- maximum protection (weeks 0 to 6)[edit | edit source]

- Cast or boot for 6 weeks

- Elevate the ankle above the heart

- Non-weight bearing x 6 weeks

- Multi-plane hip strenthening

- Core and upper extremity strengthening

Phase 2- range of motion and early strengthening (weeks 6 to 8)[edit | edit source]

- Gradual progression to full weight bearing

- Restoration of normal gait mechanics

- Full active and passive ROM all planes

- Strong emphasis on restoring full dorsiflexion

- Isometric and early isotonic ankle

- Foot intrinsic strengthening

- Bilateral progressing to unilateral squat, step and matrix progression

- Proprioception training

- Non-impact cardiovascular work

Phase 3- progressive strengthening (weeks 8 to 12)[edit | edit source]

- Restoration of full range of motion all planes

- Advance ankle and foot intrinsic strengthening

- Pool running progressing to dry land

- Linear progressing to lateral and rotational functional movements

- Bilateral progressing to unilateral plyometric activity

Phase 4- advanced strengthening (weeks 12-16)[edit | edit source]

- Advance impact and functional progressing

- Sport specific drills on field or court with functional brace

- Sport test at 3-4 months based on progress [15].

For a long-term care in order to reduce a fracture risk it is important to:

- Wear appropriate footwear;

- Follow a diet full of calcium-rich foods such as milk, yogurt, and cheese to help build bone strength;

- Do weight-bearing exercises to help strengthen bones.[11]

Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 https://www.uptodate.com/contents/stress-fractures-of-the-tibia-and-fibula (accessed 27 Januar 2019).

- ↑ https://ukhealthcare.uky.edu/orthopaedic-surgery-sports-medicine/sports-medicine/coaches-trainers/fibular-fracture (accessed 2 Februar 2019).

- ↑ Zammit J, Singh D. The peroneus quartus muscle. Anatomy and clinical relevance. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2003; 85:1134.

- ↑ Horwitz DS, Kubiak EN. Surgical treatment of osteoporotic fractures about the knee. Instr Course Lect 2010. 59:511-23.

- ↑ Lauge-Hansen N: Fractures of the ankle: combined experimental-surgical and experimental-roentgenologic investigations. Arch Surg 1950;60(5):957-985

- ↑ Hasselman CT, Vogt MT, Stone KL, et al. Foot and ankle fractures in elderly white women. Incidence and risk factors. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2003; 85-A:820.

- ↑ Makwana NK, Bhowal B, Harper WM, Hui AW. Conservative versus operative treatment for displaced ankle fractures in patients over 55 years of age. A prospective, randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001; 83:525.

- ↑ Kelsey JL, Keegan TH, Prill MM, et al. Risk factors for fracture of the shafts of the tibia and fibula in older individuals. Osteoporos Int 2006; 17:143.

- ↑ Slauterbeck JR, Shapiro MS, Liu S, Finerman GA. Traumatic fibular shaft fractures in athletes. Am J Sports Med 1995; 23:751.

- ↑ Patton A, Bourne J, Theis JC. Patterns of lower limb fractures sustained during snowsports in Otago, New Zealand. N Z Med J 2010; 123:20.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/315565.php (accessed 28 januar 2019).

- ↑ https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/826304-differential (accessed 28 Januar 2019).

- ↑ http://teachmesurgery.com/orthopaedic/ankle-and-foot/tibia-fibula-fractures/ (accessed 28 Januar 2019).

- ↑ http://nwomedicine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/ProtocolAnkleORIF.pdf (accessed 28 Januar 2019).

- ↑ https://rcmclinic.com/patient-information/foot-and-ankle/orif-fibular-fracture-post-op/ (accessed 28 Januar 2019).