Fibromyalgia

Original Editors - Amanda Collard from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Lead Editors - Elaine Lonnemann Gayatri Jadav Upadhyay

Follow-Up Editors - Jackie Crush and Jonathan Ke from Bellarmine University

Definition/Description[1][edit | edit source]

Fibromyalgia Syndrome (FMS) is one of the largest groups of soft-tissue syndromes, characterized by widespread chronic, unrelenting pain. It is considered as a systemic problem involving biochemical, neuroendocrine, and physiologic abnormalities, leading to a disorder of pain processing and perception (i.e. allodynia, hyperalgesia). The symptoms associated with FMS may originate from primary or secondary/reactive causes. FMS is NOT just one condition; it's a complex syndrome involving many different factors that can severely impact and disrupt a person’s daily life.

Prevalence[1][edit | edit source]

FMS occurs in more than 6 million Americans, causing it to be the most common musculoskeletal disorder in the U.S. It affects mainly women (90%) more often than men. Symptoms typically present between the ages of 20-55 years, but individuals have been diagnosed as young as 6 years and as old as 85 years of age.

Pathophysiology[1][edit | edit source]

The pathogenesis of FMS is theorized to be a malfunctioning of the central nervous system (CNS), characterized by central sensitization, which is a heightened pain perception accompanied by ineffective pain inhibition and/or modulation. This increased response to peripheral stimuli causes hyperalgesia, allodynia, and referred pain across multiple spinal segments, resulting in chronic widespread pain and decreased tolerance to sensory input of the musculoskeletal system.

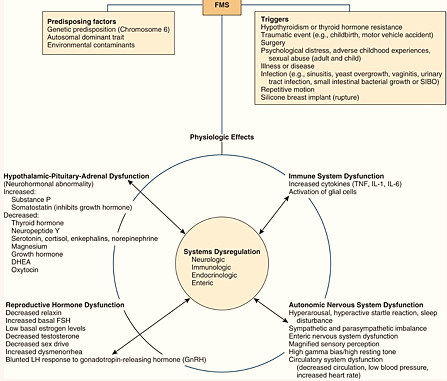

FMS systemically causes a dysregulation of neurologic, immunologic, endocrinologic, and enteric organ systems.

Autonomic Nervous System[edit | edit source]

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is responsible for regulating the Sympathetic (“fight or flight”) and the Parasympathetic (“rest and digest”) responses. With FMS, patients experience a systemically heightened sympathetic (SNS) response with a diminished parasympathetic (PNS) modulation. Continuous over activation of the SNS results in increased heart rate, excessive gastric secretions and contractions, abnormalities of smooth muscle contraction throughout the digestive tract, rapid and shallow respiration, and vasoconstriction. This can lead to malnutrition due to absorption and digestion disruptions. Prolonged inhibition of PNS alters the neuroimmunoendocrine systems, directly affecting growth hormone secretion by the pituitary gland. This can result in nonrestorative sleep, pain, fatigue, and cognitive/mood symptoms. [1]

Immune System[edit | edit source]

The immune response to infection, inflammation, and/or trauma is a release of cytokines for local healing, which trigger the CNS to release glial cells within the brain and spinal cord for healing support and pain response. With FMS, this auto-immune response is heightened, causing an excess of glia in the body which creates an exaggerated state of pain (chronic).[1]

Systems dysregulation by physiological effects of FMS:

[Chart courtesy of Catherine Goodman and Kendra Fuller: Authors of Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. ]

Causes[1][edit | edit source]

There are many hypotheses of how multiple factors play a role in the development of FMS. The exact etiology of FMS is still being researched; however, there are several potential causes and risk factors, listed below, that are currently associated with, or increase one’s risk for developing this condition.

- Diet

- Viral

- Occupation, seasonal, environmental influences

- Adverse childhood experiences (i.e. PTSD)

- Psychological and cognitive/behavioral factors

- Other conditions: RA, systemic lupus erythematosus, or AS

Current research remains inconclusive regarding genetic or hereditary cause of FMS.

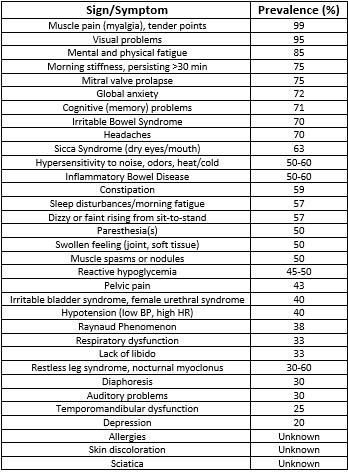

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[1] [2][edit | edit source]

Muscle pain is characterized as the major symptom of FMS, often described by patients as “aching or burning” regardless of physical activity. Other symptoms or associated problems occur, with various reports of frequencies, that can also affect function. FMS may cause residual pain sensations at a lower intensity due to repetitive exposure to peripheral stimuli or activity, also known as the “Wind-up Response.”

Symptoms are often exacerbated by:

- Stress

- Overloading physical activity

- Overstretching

- Damp or chilly weather

- Heat exposure of humidity

- Sudden change in barometric pressure

- Trauma

- Another illness

Associated Co-morbidities[1][edit | edit source]

Those with FMS are likely to present with several co-morbidities. It is important that a diagnosis of FMS is not overlooked given the presence of additional co-morbidities more commonly diagnosed. Below is a list of common co-morbidities associated with FMS:

- Sleep disturbances / apnea

- Depression

- Anxiety

- PTSD

Diagnostic Tests / Lab Tests & Values[1][3][4][5][6][edit | edit source]

There is no definitive diagnostic test currently available to determine the presence of FMS. A diagnosis of FMS is generally made based upon the results of a physical examination and ruling out other similar conditions. No special laboratory or radiologic testing is necessary for making a diagnosis; however, some recommended lab tests can be performed in order to rule out other conditions. These tests used to rule out include: CBC, ESR, basic chemistry (blood urea nitrogen, creatine, hepatic enzymes, serum calcium), thyroid levels (TSH, T3, and T4), and Rheumatoid factor.

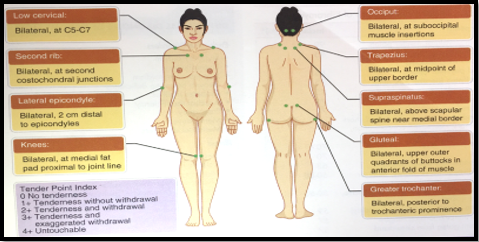

1. The American College of Rheumatology (ACR) uses two criteria for medical diagnosis[1][3]

a. Widespread (four-quadrant) pain both above and below the waistline present for at least 3 months

b. Tenderness on pressure (tender points) of at least 11 of 18 specified sites and the presence of widespread pain for diagnosis

[Chart courtesy of Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. 4th]

2. Symptom Intensity Scale [1][3][4]

a. To help differentiate FMS from other rheumatologic conditions

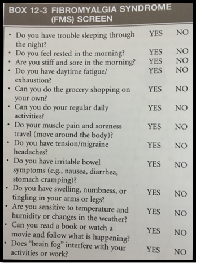

3. Fibromyalgia Syndrome Screen [1]

a. To identify potential cases of FMS, but should not be relied on as

the only evaluation instrument

4. The Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR) consists of

3 domains [5]

a. 9 questions about function

b. 2 questions regarding global impact

c. 10 questions about symptoms

5. Sleep Disorder Screening [6]

a. To screen for Circadian Rhythm Sleep Disorders (CRSD)

Medical Management (current best evidence)[edit | edit source]

As there is currently no cure or definitive treatment protocol for the disorder, FMS research and support organizations offer those with the disease several recommendations for minimizing the negative impact that the condition may bestow on patient's daily lives. The aim of self-management techniques is to decrease the stress on an already dysregulated response system. Along with self-management, there are additional means of medical management for those with FMS. The following means for management are all prescribed treatment methods for those with the disorder.

Medication[1][edit | edit source]

Several prescription medications are available for patients suffering from symptoms associated with FMS. Each medication aims to treat different symptoms or co-morbidities associated with the condition; therefore, there are multiple options to discuss with a physician. Here is a list of several options, but the list is NOT exclusive:

- NSAIDs, Acetaminophen, Tramadol – To relieve pain and inflammation

- Cyclobenzaprine – To reduce pain and improve sleep patterns

- Antidepressants (Cimbalta, Amitriptyline, Trazadone) – To reduce pain, improve sleep, and treat underlying mood disorders

- Anticonvulsants (Lyrica) – To reduce pain and improve sleep problems (Limited evidence to support this group of medications)

Education[7][8][edit | edit source]

Education about the pathophysiology and the neuroscience behind the condition is the most effective method in reducing catastrophizing pain symptoms in patients experiencing FMS according to current research. Simple acknowledgement and explanation of symptoms and relaxation strategies can alter a patient’s ability to cope with their condition.

- Explanation of disorder

- Reassurance of condition and symptoms

- Activity management - Pacing, self-monitoring, rest breaks, AVOID exacerbations, set realistic activity goals, etc.

- Relaxation Techniques - Minimize environmental stress, deep breathing, healthy & active lifestyle habits, adequate sleep, therapeutic massage, etc.

Physical Therapy & Exercise[1][9][10][1][2][3][4][edit | edit source]

PATIENT EDUCATION[edit | edit source]

SeeEducationsection above

[Example of a Physical Therapist providing a patient with the educational tools to manage their condition and rehabilitation process.]

AEROBIC & RESISTANCE EXERCISE[1][9][edit | edit source]

According to the Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2008), supervised light aerobic exercise and strength/resistance training is highly recommended for the management of patients with chronic pain, like those with FMS. It has been found to increase their capacity for activity while minimizing their symptoms associated with FMS. Specifically, aerobic activity has been shown to improve psychological symptoms associated with depression, cognitive decline, and sleep disturbances. Exercise also improves patient’s cellular metabolism and respiratory capacity, increases lean muscle mass and tone, and increases oxygen uptake within the body’s system(s), which ultimately minimizes their complaints of chronic pain and fatigue.

MANUAL / PASSIVE THERAPY>[10][1][2][edit | edit source]

Some studies support that TENS and joint mobilizations foster the reduction of pain as short term relief in patients with FMS. Specifically, patients with chronic back pain due to FMS may benefit from spinal manipulations with limited evidence to support this modality. Moderate evidence shows that the use of passive STM is helpful with pain regulation. In addition, diffuse chronic pain presentations are less likely to be reliable for medical management with TENS compared to localized pain. Passive therapy should not be the foundation of FMS medical management due to the maladaptive illness beliefs and coping strategies for patients’ pain.

Manual lymph drainage therapy and connective tissue massage have also been studied in women with fibromyalgia. Researchers used the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire and the Nottingham Health Profile to measure the impact of the treatment. Their research suggests that both manual lymph drainage therapy and connective tissue massage show improvements in both the FIQ and the Nottingham Health Profile. However, there were significantly greater improvements in the group that received manual lymph drainage therapy, suggesting that manual lymphatic drainage therapy may be preferred over connective tissue massage.

AQUATIC THERAPY & BALNEOTHERAPY [3][4][edit | edit source]

Recent research has proven that aquatic therapy is a more tolerable workout for people with FMS pain. The water’s buoyancy allows the patient to maintain active movement without exerting excessive energy and/or increasing pressure on their joints. Furthermore, evidence has shown that aquatic therapy and hydrotherapy help in improving the quality of life of those with FMS long term. The underlying symptom(s) of fibromyalgia, central hypersensitivity and pain, may be alleviated by the hydrostatic pressure and the effects of soothing temperature on the nerve endings, along with general muscle relaxation

Ideal pool temperature for aquatic therapy sessions are between 84o F and 90o F

- 82o F and 84o F for the general population

- 90o F and 94o F for people with arthritic conditions

An exercise-education program showed a small significant improvement in health status in patients with fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain, compared with education only. Patients with milder symptoms improved most with this treatment. Moreover, it has been shown that thermal mud baths (and other balneotherapy methods) increase plasma levels of beta-endorphins, thus explaining their analgesic and anti-spastic effects, which is particularly important in patients with FMS.

Occupational Therapy [5][edit | edit source]

Treatment focuses on activity modification principles, such as working at a moderate pace, frequent positional/postural changes, and resting before fatigue sets in. Patients are encouraged to incorporate regulating principles into all areas of life including self-care, work, and leisure. Proper body mechanics and posture related to home management and work activities are evaluated and adjusted per individual.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy [6][7][8][edit | edit source]

Research performed by Moseley supports the relationship between pain association and beliefs with physical performance. There is evidence that supports the consideration of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) to be implemented in the assessment and plan of care of patients with chronic pain. Growing evidence continues to demonstrate that CBT shows improvement in reports of pain, reduces hyperalgesia, and chronic pain-related brain response in FMS.

One study found that behavioral insomnia therapy for patients with FMS may have a promising impact. The study incorporated patient education on sleeping habits and proper sleeping schedules to reduce the bouts of insomnia experienced by those with fibromyalgia. The researchers concluded that patients who received the behavioral therapy experienced improvement in how long they slept and in their general condition compared to other groups.

Chiropractic care & Massage [9][edit | edit source]

There is no evidence to support chiropractic care nor therapeutic massage as effective in pain management.

Acupuncture [10][edit | edit source]

While many patients explore this option for relief of pain and fatigue, acupuncture techniques have weak evidence to support their effectiveness in current literature.

Alternative/Holistic Management[edit | edit source]

No evidence to support alternative/holistic management.

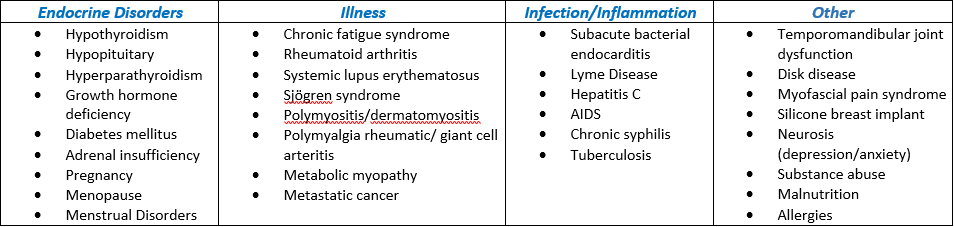

Differential Diagnosis [1][edit | edit source]

The following are all differential diagnoses for FMS. It is possible for several to be present concurrently. Moreover, it is important to determine the presence of all potential facets and diagnoses in order to successfully treat a patient with suspected fibromyalgia.

Case Reports[edit | edit source]

A case-control study examining the role of physical trauma in the onset of fibromyalgia syndrome (Full Text Here)

Tailored cognitive-behavioral therapy for fibromyalgia: Two case studies. (Abstract Here)

Insular hypometabolism in a patient with Fibromyalgia: A case study. (Abstract Here)

Resources[edit | edit source]

National Fibromyalgia Association

APTA Conservative PT Management for Fibromyalgia

APTA Recommendation for "Best Workout Options" for Chronic Pain

Ted Talk - A short lecture discussing the perception of pain can pose as an example of how to approach educating patients with chronic and/or catastrophizing pain symptoms, like Patient with FMS.

References

[edit | edit source]

1. Goodman, Catherine and Fuller Kendra. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. Philadelphia, WB Saunders. 4th edition (Goodman & Fuller), 2014. (pp. 310-317)

2. Solano C, Martinez A, Martinez-Lavin M, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in fibromyalgia assessed by the Composite Autonomic Symptoms Scale (COMPASS). Journal Of Clinical Rheumatology: Practical Reports On Rheumatic & Musculoskeletal Diseases [serial online]. June 2009;15(4):172-176. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

3. Wolfe F, Clauw D, Yunus M, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care & Research [serial online]. May 2010;62(5):600-610. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

4. Wolfe F, Rasker J. The Symptom Intensity Scale, Fibromyalgia, and the Meaning of Fibromyalgia-like Symptoms. Journal Of Rheumatology [serial online]. November 2006;33(11):2291-2299. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

5. Bennett R, Friend R, Jones K, Ward R, Han B, Ross R. The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Research & Therapy [serial online]. 2009;11(4):R120. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

6. Korszun A. Sleep and circadian rhythm disorders in fibromyalgia. Current Rheumatology Reports [serial online]. April 2000;2(2):124-130. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

7. Moseley GL. Widespread brain activity during an abdominal task markedly reduced after pain physiology education: fMRI evaluation of a single patient with chronic low back pain. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51:49–52.

8. Meeus M,Nijs J,VanOosterwijck J,etal.Painphysiologyeducation improvespainbeliefsinpatientswithchronicfatiguesyndromecompared topacingandself-managementeducation:adouble-blindrandomised controlledtrial.ArchPhys MedRehabil.2010;91:1153–1159.

9. Brosseau L, Wells G, Veilleux L, et al. Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic fitness exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 1. Physical Therapy [serial online]. July 2008;88(7):857-871. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 4, 2017.

10. Skyba DA, Radhakrishnan R, Rohlwing JJ, et al. Joint manipulation reduces hyperalgesia by activation of monoamine receptors but not opioid or GABA receptors in the spinal cord. Pain. 2003;106:159–168.

11. Lofgren M, Norrbrink C. Pain relief in women with fibromyalgia: a cross-over study of superficial warmth stimulation and transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation. J Rehabil Med.2009;41:557–562.

12. Ekici G, Bakar Y, Akbayrak T, Yuksel I. Comparison of manual lymph drainage therapy and connective tissue massage in women with fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal Of Manipulative & Physiological Therapeutics [serial online]. February 2009;32(2S):127-133. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 5, 2017.

13. Mannerkorpi K, Nordeman L, Ericsson A, et al. Pool exercise for patients with fibromyalgia or chronic widespread pain: a randomized controlled trial and subgroup analyses. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:751–760.

14. Bazzichi L, Da Valle Y, Lucacchini A, et al. A multidisciplinary approach to study the effects of balneotherapy and mud-bath therapy treatments on fibromyalgia. Clinical And Experimental Rheumatology [serial online]. November 2013;31(6 Suppl 79):S111-S120. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 4, 2017.

15. Poole J, Siegel P. Effectiveness of Occupational Therapy Interventions for Adults With Fibromyalgia: A Systematic Review. American Journal Of Occupational Therapy [serial online]. January 2017;71(1):1-10. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 4, 2017.

16. Moseley GL. Evidence for a direct relationship between cognitive and physical change during an education intervention in people with chronic low back pain. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:39–45.

17. Lazaridou A, Jieun K, Kim J, et al. Effects of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (CBT) on Brain Connectivity Supporting Catastrophizing in Fibromyalgia. Clinical Journal Of Pain [serial online]. March 2017;33(3):215-221. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 5, 2017.

18. Martínez M, Miró E, Buela-Casal G, et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia and sleep hygiene in fibromyalgia: a randomized controlled trial. Journal Of Behavioral Medicine [serial online]. August 2014;37(4):683-697. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed

19. Wise P, Walsh M. Chiropractic treatment of fibromyalgia: two case studies. Chiropractic Journal Of Australia [serial online]. June 2001;31(2):42-46. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 5, 2017.

20. Carville SF, Arendt-Nielsen S, Bliddal H, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia syndrome. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:536–541.

21. Carey, W. D., & Cleveland Clinic Foundation. (2010). Current clinical medicine (2nd ed.). Philadelphia: Saunders Elsevier.

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 1.12 1.13 1.14 1.15 1.16 1.17 Goodman, Catherine and Fuller Kendra. Pathology: Implications for the Physical Therapist. Philadelphia, WB Saunders. 4th edition (Goodman & Fuller), 2014. (pp. 310-317)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Solano C, Martinez A, Martinez-Lavin M, et al. Autonomic dysfunction in fibromyalgia assessed by the Composite Autonomic Symptoms Scale (COMPASS). Journal Of Clinical Rheumatology: Practical Reports On Rheumatic & Musculoskeletal Diseases [serial online]. June 2009;15(4):172-176. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Wolfe F, Clauw D, Yunus M, et al. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care & Research [serial online]. May 2010;62(5):600-610. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Wolfe F, Rasker J. The Symptom Intensity Scale, Fibromyalgia, and the Meaning of Fibromyalgia-like Symptoms. Journal Of Rheumatology [serial online]. November 2006;33(11):2291-2299. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bennett R, Friend R, Jones K, Ward R, Han B, Ross R. The Revised Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (FIQR): validation and psychometric properties. Arthritis Research & Therapy [serial online]. 2009;11(4):R120. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Korszun A. Sleep and circadian rhythm disorders in fibromyalgia. Current Rheumatology Reports [serial online]. April 2000;2(2):124-130. Available from: MEDLINE, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 2, 2017.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Moseley GL. Widespread brain activity during an abdominal task markedly reduced after pain physiology education: fMRI evaluation of a single patient with chronic low back pain. Aust J Physiother. 2005;51:49–52.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Meeus M,Nijs J,VanOosterwijck J,etal.Painphysiologyeducation improvespainbeliefsinpatientswithchronicfatiguesyndromecompared topacingandself-managementeducation:adouble-blindrandomised controlledtrial.ArchPhys MedRehabil.2010;91:1153–1159.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Brosseau L, Wells G, Veilleux L, et al. Ottawa Panel evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for aerobic fitness exercises in the management of fibromyalgia: part 1. Physical Therapy [serial online]. July 2008;88(7):857-871. Available from: CINAHL, Ipswich, MA. Accessed April 4, 2017.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Skyba DA, Radhakrishnan R, Rohlwing JJ, et al. Joint manipulation reduces hyperalgesia by activation of monoamine receptors but not opioid or GABA receptors in the spinal cord. Pain. 2003;106:159–168.