Medical Cannabis

Original Editors -Mark Wojda from Bellarmine University's Pathophysiology of Complex Patient Problems project.

Top Contributors - Ryan Scinta, Lucinda hampton, Elaine Lonnemann, Kim Jackson, Ryan Barry, WikiSysop, Mark Wojda and Joseph Ayotunde Aderonmu

Definition/Description:[edit | edit source]

As a result of cannabis decriminalization and legalization throughout the world, healthcare professionals are faced with more questions from patients regarding cannabis and its use. Healthcare professionals have a responsibility to provide evidence-based guidance on this important medical and social issue. Cannabis has significant health benefits and therapeutic applications to a vast array of medical conditions explored in this page. As with any medical substance, cannabis use also presents with associated risks. This page describes the many uses of cannabis in relation to specific patient populations. The purpose of this page is to provide a comprehensive, up-to-date educational resource for healthcare professionals, patients, and caregivers guided by current evidence-based research. Additionally, the information presented will attempt to dispel many myths and help clear the smoke around issues surrounding the cannabis plant. This page will be updated continually in the future. This page is dedicated to past and future patients.

Cannabis is classified as a member of the cannabaceae plant family. Cannabis is classified under the single species of hemp (C. sativa). The female version of hemp is considered “marijuana” and consists of the indica, sativa, and ruderalis varieties. Cannabis has thousands of varieties and the effects of each variety are different. Hops belongs to the cannabaceae plant family as well. Hops is used in the production of beer, a celebrated legal drug.

[1][2]

Marijuana and Related Cannabinoids

[edit | edit source]

There are two main chemical cannabinoids that have been extensively studied for their effects on the different body systems. These two substances are Tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and Cannabidiol (CBD). THC is the chemical responsible for the psychotropic effects associated with smoking or ingesting marijuana. CBD on the other hand, does not have psychoactive properties and may balance or inhibit the psychotropic effects of THC. CBD may be more important than THC in producing therapeutic effects such as analgesia, decreased inflammation, decreased spasticity, and antiseizure effects. [3]

Federal Classification

[edit | edit source]

1970 - The Federal classification of cannabis legally: Schedule 1 narcotic, no accepted medical value.

As defined by the United States Controlled Substance Act (CSA).

“Schedule I drugs are defined as:

(A) The drug or other substance has a high potential for abuse.

(B) The drug or other substance has no currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States.

(C) There is a lack of accepted safety for use of the drug or other substance under medical supervision.”

[4]

Until recently, this classification had removed marijuana as a medicinal agent and severely restricted any research into its potential clinical benefits. For example, it is difficult to perform well-controlled clinical trials on a substance when the government has determined that the substance has no clinical applications. [3]

However, now that more and more states are starting to leglaize the use of medical and recreational marijuana, better studies may soon start to arise in the literature.

State Classifications

[edit | edit source]

As of June, 2016, 28 states plus District of Columbia, Guam, and Puerto Rico now allow for comprehensive public medical marijuana and cannabis programs.

California - Became the first state to legalize cannabis for medical use in 1996.

Colorado and Washington - November, 2012 they became the first two states to legalize recreational use of marijuana for individuals over the age of 21 (Colorado Amendment 64 and Washington Initiative 502).

Oregon - June, 2010 Oregon Board of Pharmacy reclassified marijuana from a Schedule I drug to a Schedule II drug. Oregon is the first state in the nation to make marijuana anything less than a Schedule I drug. [5]

Patient Demongraphics and Self Reported Usage

[edit | edit source]

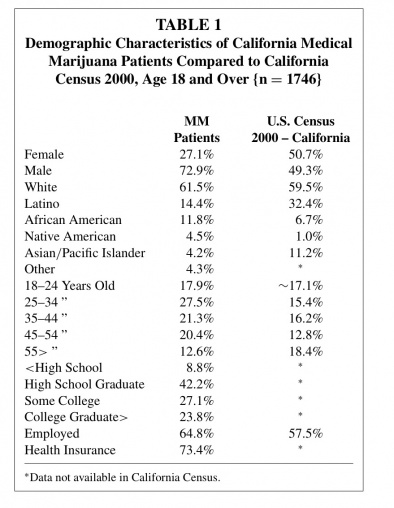

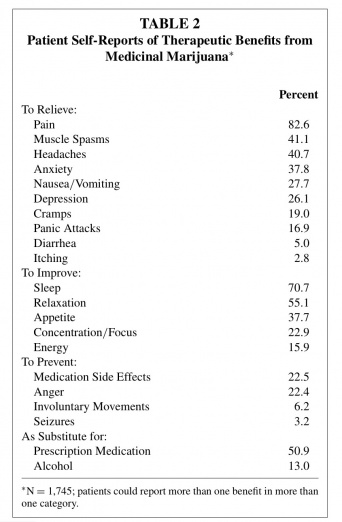

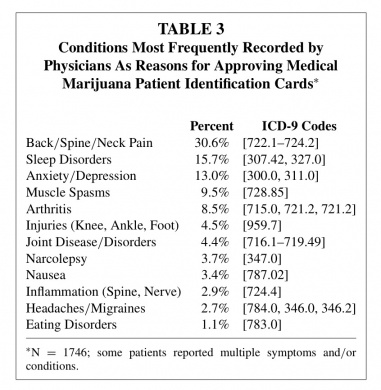

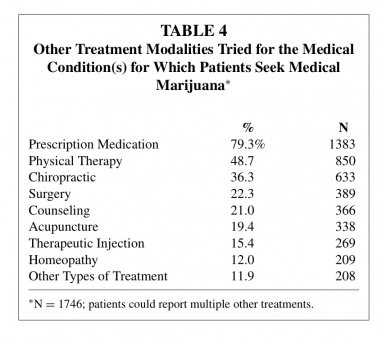

Information for the following tables was gathered from a sample of 1,746 patients of nine medical marijuana evaluation clinics in California. These table may provide insight about potential patients based on demographics and conditions.

From: Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLCISSN: 0279-1072 print/2159-9777 online DOI: 10.1080/02791072.2011.587700

Health Effects of Cannabis and Cannabinoids

[edit | edit source]

This section of the page will be continuously updated.

The National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine worked together to create a comprehensive report for the current state of evidence regarding what is known about the health effects of cannabis and cannabis derived products. Below are the conclusions of these findings.

The committee developed standard language to categorize the weight of the evidence regarding whether cannabis or cannabinoids used for therapeutic purposes are an effective or ineffective treatment for certain prioritized health conditions, or whether cannabis or cannabinoids used primarily for recreational purposes are statistically associated with certain prioritized health conditions. The conclusions from this research are organized by level of evidence:

- Conclusive Evidence: strong evidence from RCTs to support or refute the conclusion. Firm conclusions can be made and the limitations to the evidence, including chance, bias, and/or confounding factors can be ruled out with reasonable confidence.

- Substantial Evidence: At this level, there are several supportive findings from good-quality studies with very few or no credible opposing findings. Firm conclusion can be made, but minor limitations, can’t be ruled out with reasonable confidence.

- Moderate Evidence: There are several findings from good to fair quality studies with very few or no credible opposing findings. General conclusions can be made but not without having a general limitation.

- Limited Evidence: There are supportive findings from fair-quality studies or mixed findings with most favoring one conclusion. Conclusions can be made but with significant uncertainty due to various limitations.

- No or Insufficient Evidence: There are mixed findings, a single poor study, or this factor hasn't been studied at all. No conclusion can be made because of substantial uncertainty due to various limitations or lack of evidence.

Conclusions for: Therapeutic Effects (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/6)

Conclusive or Substantial Evidence for effectiveness:

- Treatment of chronic pain in adults.

- Antiemetics in the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting.

- Improving patient-reported multiple sclerosis (MS) spasticity symptoms.

Moderate Evidence for effectiveness:

- Improving short term sleep outcomes in individuals with sleep disturbances associated with obstructive sleep apnea, fibromyalgia, chronic pain, and multiple sclerosis.

Limited Evidence for effectiveness:

- Increasing appetite and decreasing weight loss associated with HIV/AIDS

- Improving clinician-measured MS spasticity symptoms

- Improving symptoms of Tourette’s Syndrome

- Improving anxiety symptoms, as assessed by a public speaking test, in individuals with social anxiety disorders.

- Improving symptoms of PTSD

Limited Evidence of a statistical correlation between cannabinoids and:

- Better outcomes (mortality and disability) after a TBI or intracranial hemorrhage.

Limited Evidence for ineffectiveness of:

- Improving symptoms associated with dementia

- Improving intraocular pressure associated with glaucoma

- Reducing depressive symptoms in individuals with chronic pain or MS

Insufficient Evidence to support or refute the conclusion for effective treatment for:

- Cancers, including glioma.

- Cancer-associated anorexia cachexia syndrome and anorexia nervosa.

- Symptoms of IBS

- Epilepsy

- Spasticity in patients with paralysis due to SCI

- Symptoms associated with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis.

- Chorea and certain neuropsychiatric symptoms with Huntington’s Disease.

- Motor system symptoms associated with Parkinson’s disease or the levodopa-induced dyskinesia.

- Dystonia

- Achieving abstinence inthe abuse of addictive substances

- Mental health outcomes in individuals with schizophrenia or schizophreniform psychosis.

Conclusions for: Cancer (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/7 )

Moderate Evidence of no statistical association between cannabis use and:

- Incidence of lung cancer or head and neck cancers

Limited Evidence of a statistical association between cannabis smoking and:

- Non-seminoma-type testicular germ cell tumors

No or Insufficient Evidence to support or refute any association between cannabis and:

- Incidence of esophageal cancer

- Incidence of prostate cancer, cervical cancer, malignant gliomas, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, pencils cancer, anal cancer, Kaposi’s sarcoma, or bladder cancer.

- Subsequent risk of developing acute myeloid leukemia/acute non-lymphoblastic leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, rhahbomyosarcoma, astrocytoma, or neuroblastoma in offspring.

Conclusions for: Cardiometabolic Risk (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/8 )

Limited Evidence of a statistical correlation between cannabis use and:

- Triggering of acute myocardial infarction

- Ischemic stroke and subarachnoid hemorrhage

- Decreased risk of metabolic syndrome and diabetes Increased risk of prediabetes.

No Evidence to support or refute a statistical correlation between chronic effects of cannabis use and:

- Increased risk of acute myocardial infarction.

Conclusions for: Respiratory Disease (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/9 )

Substantial Evidence of a statistical association between cannabis smoking and:

- Worse respiratory symptoms and more frequent chronic bronchitis episodes (long-term cannabis smoking)

Moderate evidence of a statistical association between cannabis smoking and:

- Improved airway dynamics with acute use, but not with chronic use.

- Higher forced vital capacity (FVC)

Moderate Evidence of a statistical association between the cessation of cannabis smoking and:

- Improvements in respiratory symptoms.

Limited Evidence of a statistical association between cannabis smoking and:

- An increased risk of developing COPD when controlled for tobaccos use (occasional cannabis smoking).

No or Insufficient Evidence to support or refute a statistical association:

- Hospital admissions for COPD

- Asthma development or asthma exacerbations

Conclusions for: Immunity (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/10 )

There is limited evidence of a statistical association between cannabis smoking and:

- A decrease in the production of several in ammatory cytokines in healthy individuals

There is limited evidence of no statistical association between cannabis use and:

- The progression of liver brosis or hepatic disease in individuals with viral Hepatitis C (HCV) (daily cannabis use)

There is no or insufficient evidence to support or refute a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- Other adverse immune cell responses in healthy individuals (cannabis smoking)

- Adverse effects on immune status in individuals with HIV (cannabis or dronabinol use)

Increased incidence of oral human papilloma virus (HPV) (regular cannabis use).

Conclusions for: Injury and Death (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/11 )

There is substantial evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- Increased risk of motor vehicle crashes

There is moderate evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- Increased risk of overdose injuries, including respiratory distress, among pediatric populations in U.S. states where cannabis is legal

There is no or insufficient evidence to support or refute a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- All-cause mortality (self-reported cannabis use)

- Occupational accidents or injuries (general, non-medical cannabis use)

- Death due to cannabis overdose

Conclusions for: Prenatal, Perinatal, and Neonatal Exposure (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/12 )

There is substantial evidence of a statistical association between maternal cannabis smoking and:

- Lower birth weight of the offspring

There is limited evidence of a statistical association between maternal cannabis smoking and:

- Pregnancy complications for the mother

- Admission of the infant to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU)

There is insufficient evidence to support or refute a statistical association between maternal cannabis smoking and:

- Later outcomes in the offspring (e.g., sudden infant death syndrome, cognition/academic achievement, and later substance use)

Conclusions for: Psychosocial (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/13 )

There is moderate evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

The impairment in the cognitive domains of learning, memory, and attention (acute cannabis use)

There is limited evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- Impaired academic achievement and education outcomes.

- Increased rates of unemployment and/or low income.

- Impaired social functioning or engagement in developmentally appropriate social roles.

There is limited evidence of a statistical association between sustained abstinence from cannabis use and:

- Impairments in the cognitive domains of learning, memory, and attention

Conclusions for: Mental Health (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/14 )

There is substantial evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- The development of schizophrenia or other psychoses, with the highest risk among the most frequent users

There is moderate evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- Better cognitive performance among individuals with psychotic disorders and a history of cannabis use

- Increased symptoms of mania and hypomania in individuals diagnosed with bipolar disorders (regular cannabis use).

- A small increased risk for the development of depressive disorders

- Increased incidence of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts with a higher incidence among heavier users

- Increased incidence of suicide completion.

- Increased incidence of social anxiety disorder (regular cannabis use)

There is moderate evidence of no statistical association between cannabis use and:

- Worsening of negative symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., blunted affect) among individuals with psychotic disorders.

There is limited evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- An increase in positive symptoms of schizophrenia (e.g., hallucinations) among individuals with psychotic disorders.

- The likelihood of developing bipolar disorder, particularly among regular or daily users.

- The development of any type of anxiety disorder, except social anxiety disorder.

- Increased symptoms of anxiety (near daily cannabis use)

- Increased severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms among individuals with posttraumatic stress disorder.

There is no evidence to support or refute a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- Changes in the course or symptoms of depressive disorders

- The development of posttraumatic stress disorder.

Conclusions for: Problem Cannabis Use (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/15 )

There is substantial evidence that:

- Stimulant treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) during adolescence is not a risk factor for the development of problem cannabis use.

- Being male and smoking cigarettes are risk factors for the progression of cannabis use to problem cannabis use.

- Initiating cannabis use at an earlier age is a risk factor for the development of problem cannabis use.

There is substantial evidence of a statistical association between:

- Increases in cannabis use frequency and the progression to developing problem cannabis use.

- Being male and the severity of problem cannabis use, but the recurrence of problem cannabis use does not differ between males and females.

There is moderate evidence that:

- Anxiety, personality disorders, and bipolar disorders are not risk factors for the development of problem cannabis use

- Major depressive disorder is a risk factor for the development of problem cannabis use.

- Adolescent ADHD is not a risk factor for the development of problem cannabis use.

- Being male is a risk factor for the development of problem cannabis use.

- Exposure to the combined use of abused drugs is a risk factor for the development of problem cannabis use.

- Neither alcohol nor nicotine dependence alone are risk factors for the progression from cannabis use to problem cannabis use

- During adolescence the frequency of cannabis use, oppositional behaviors, a younger age of rst alcohol use, nicotine use, parental substance use, poor school performance, antisocial behaviors, and childhood sexual abuse are risk factors for the development of problem cannabis use.

There is moderate evidence of a statistical association between:

- A persistence of problem cannabis use and a history of psychiatric treatment

- Problem cannabis use and increased severity of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms

There is limited evidence that:

- Childhood anxiety and childhood depression are risk factors for the development of problem cannabis use.

Conclusions for: Abuse of Other Substances (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/16 )

There is moderate evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- The development of substance dependence and/or substance abuse disorder for substances including alcohol, tobacco, and other illicit drugs.

There is limited evidence of a statistical association between cannabis use and:

- The initiation of tobacco use.

- Changes in the rates and use patterns of other licit and illicit substances.

Challenges and barriers to this research: (https://www.nap.edu/read/24625/chapter/17 )

- There are several challenges and barriers in conducting cannabis and cannabinoid research, including:

- There are specific regulatory barriers, including the classification of cannabis as a Schedule I substance, that impede the advancement of cannabis and cannabinoid research.

- It is often difficult for researchers to gain access to the quantity, quality, and type of cannabis product necessary to address specific research questions on the health effects of cannabis use.

- A diverse network of funders is needed to support cannabis and cannabinoid research that explores the bene cial and harmful effects of cannabis use.

- To develop conclusive evidence for the effects of cannabis use for short- and long-term health outcomes, improvements and standardization in research methodology (including those used in controlled trials and observational studies) are needed

Drug Interactions[edit | edit source]

A study in JAMA found a “25% reduction in opioid related deaths in states with medical marijuana programs.”[7] The study states, “Medical marijuana laws, when implemented, may represent a promising approach for stemming runaway rates of nonintentional opioid analgesic effects.” As the epidemic negatively impacts the country, politicians like Elizabeth Warren call for more studies to be done on cannabis to curb the destructive effects of the opioid epidemic.[8]

Additionally, “there is some evidence of cross-tolerance between cannabinoids and opioids.”[9]

Relevance to Physical Therapy Rehabilitation

[edit | edit source]

Since medical and recreational marijuana is becoming legalized in a greater number of states, there is an increased likelihood that physical therapists will treat patients using marijuana to combat different musculoskeletal and neurological conditions. Drug prescription does not fall under the scope of physical therapy practice; therefore, the major role of the therapist is to be an educational resource for patients with questions about the use of medical marijuana. It is recommended that therapists explain the benefits and drawbacks of medical marijuana rather than directly suggesting that the patient initiate using the substance. [3]

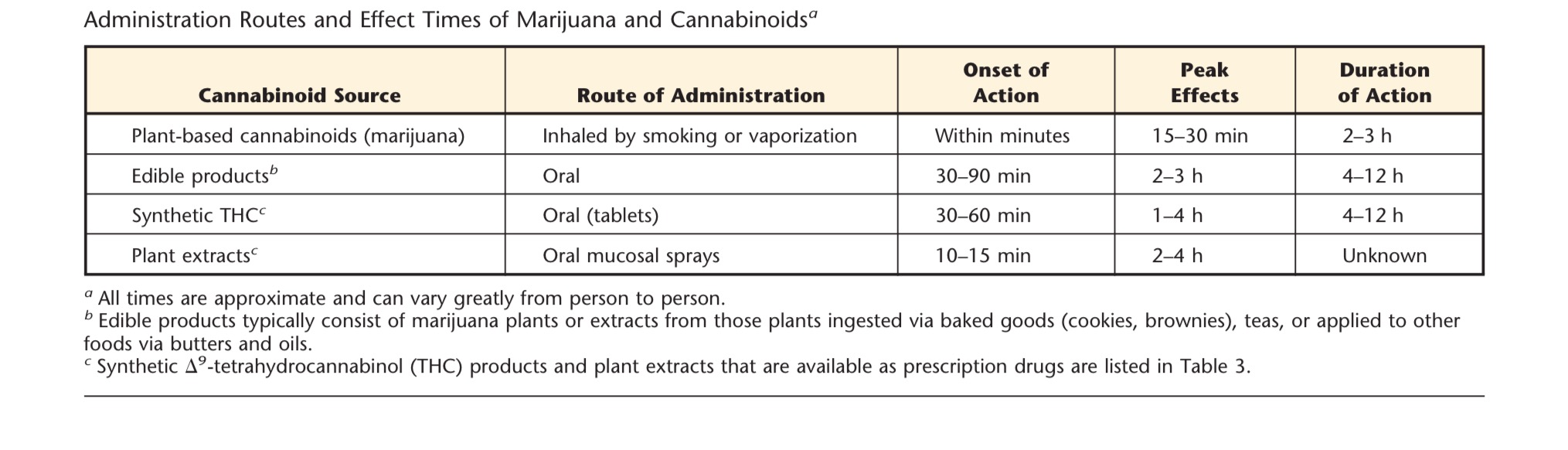

Patients may not be well educated on the different routes of administration of marijuana and its extracts. Below is a chart of different marijuana based products with their associated effect times.

Patients who are known users of medicinal or recreational marijuana for analgesic purposes should be encouraged to keep a pain journal.Therapists should have patients periodically complete valid and reliable pain scales to ensure that the treatment is providing the desirable effects. One of the major roles of the physical therapist is to monitor patients for potential abuse of the substance and/or co-administration with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or opioids. These patients may present with amplified confusion or somnolence and demonstrate personality changes or psychotic-like behaviors. If these signs are noted, the problem should be reports the prescribing physician by the therapist. [3]

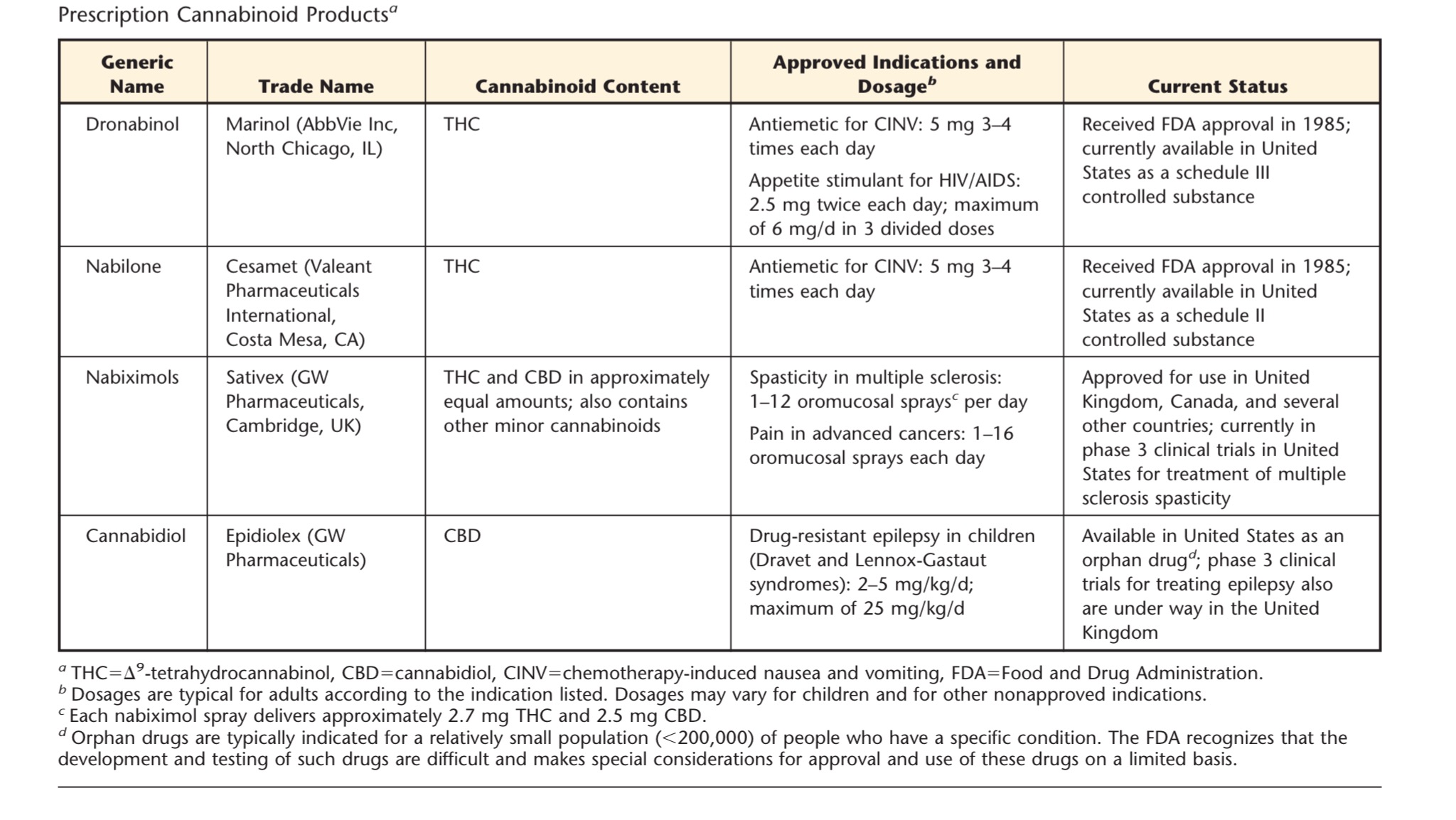

In the table below are several presecribed cannabinoid based medications that have been either been approved by the FDA or are currently under clinical trials. These drugs may start to be prescribed more in the future.

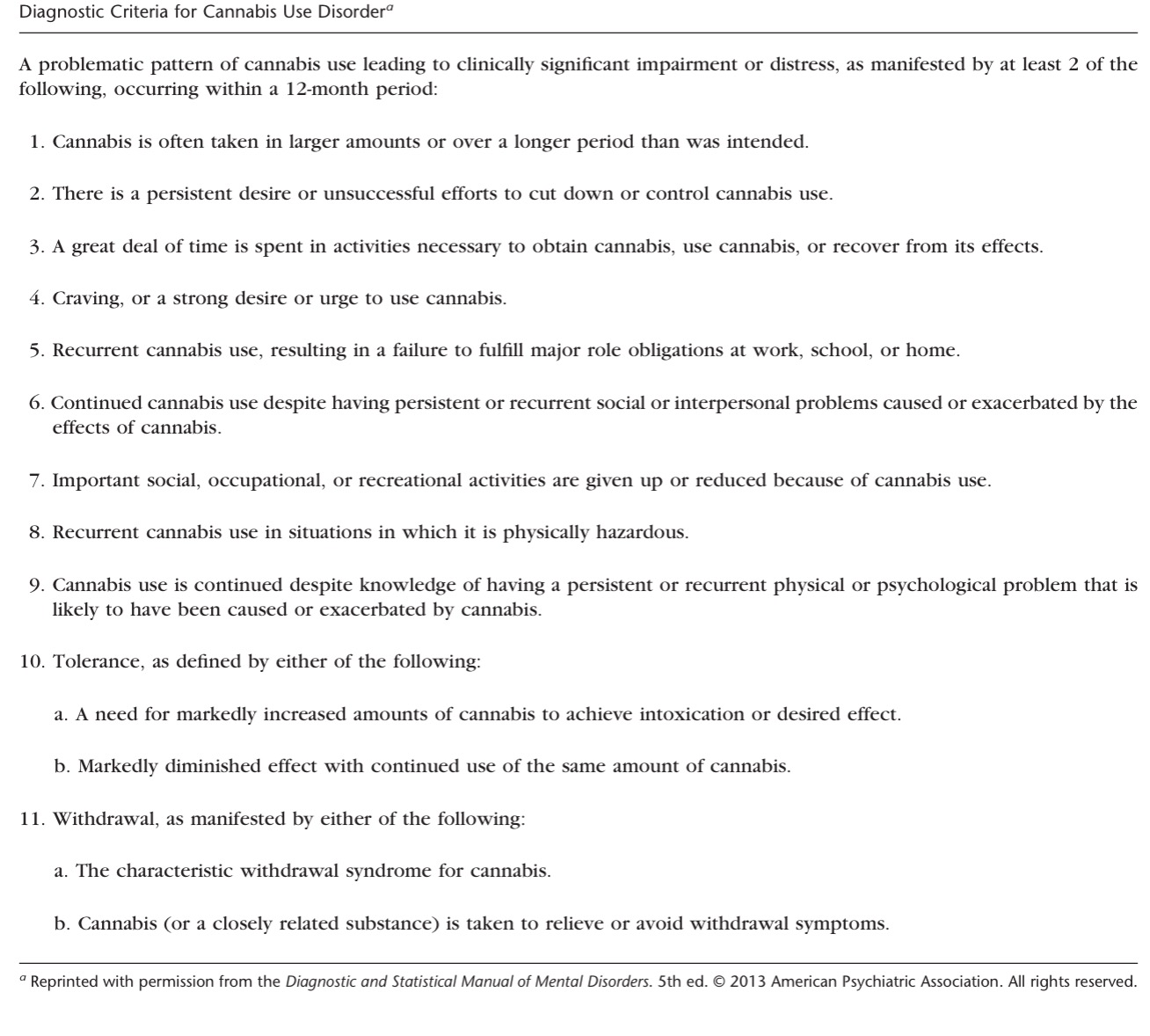

Therapists should also be able to identify patients for Cannabis Use Disorder (CUD). (See diagnostic criteria questionnaire below) Patients using marijuana for the use of chronic pain are less likely to suffer from cannabis use problems compared with individuals who used medical cannabis for other reasons (e.g., anxiety, insomnia, and muscle spasms). [10]

This has been shown to occur primarily in recreational users and risk of this disorder in individuals using medical marijuana has yet to be fully established. [11]

Case Reports/ Case Studies:

[edit | edit source]

[edit | edit source]

This page will be continually updated in the future.

HIV:

Woolridge E, Barton S, Samuel J, Osorio J, Dougherty A, Holdcroft A. Cannabis use in HIV for pain and other medical symptoms. J Pain Symptom Manage 2005;29(4):358-67.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15857739

Multiple Sclerosis:

Consroe P, Musty R, Rein J, Tillery W, Pertwee R. The perceived effects of smoked cannabis on patients with multiple sclerosis. European Neurology 1997;38:44-48.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9252798

Chong MS, Wolff K, Wise K, Tanton C, Winstock A, Silber E. Cannabis use in patients with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2006;12(5):646-51.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17086912

Spinal Cord Injury:

Malec J, Harvey RF, Cayner JJ. Cannabis effect on spasticity in spinal cord injury. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation 1982;63:116-118.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6978699

Crohn's Disease:

Lal S, Prasad N, Ryan M, Tangri S, Silverberg MS, Gordon A, Steinhart H. Cannabis use amongst patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2011;23(10):891-6.

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21795981

Resources

[edit | edit source]

For information regarding your states cannabis laws:

http://norml.org/

For information regarding which strains you or your patient's are using:

For information regarding cannabis therapeutics for different conditions including veterans:

http://www.safeaccessnow.org/

Realm of Caring: Pediatric Epilepsy

Information on legal issues: Marijuana policy project:

Drug policy information:

Recent Related Research (from Pubmed)[edit | edit source]

see tutorial on Adding PubMed Feed

Failed to load RSS feed from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/entrez/eutils/erss.cgi?rss_guid=169y_86ceC_: Error parsing XML for RSS

References[edit | edit source]

see adding references tutorial.

- ↑ Classification | USDA PLANTS [Internet]. Classification | USDA PLANTS. [cited 2016Apr13]. Retrieved from: http://plants.usda.gov/java/classificationservlet?source=display

- ↑ The Editors of Encyclopædia Britannica. cannabis [Internet]. Encyclopedia Britannica Online. Encyclopedia Britannica; [cited 2016Apr13]. Retrieved from: http://www.britannica.com/plant/cannabis-plant

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Ciccone CD. Medical Marijuana: Just the Beginning of a Long, Strange Trip? Physical Therapy. 2016;97(2):239–48.

- ↑ Controlled Substance Schedules [Internet]. Resources -. [cited 2016Apr10]. Retrieved from: http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/schedules/

- ↑ http://arcweb.sos.state.or.us/pages/rules/oars_800/oar_855/855_080.html

- ↑ National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: The current state of evidence and recommendations for research. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Doi: 10.17226/24625

- ↑ Hayes MJ, Brown MS. Medical Cannabis Laws and Opioid Mortality [Internet]. JAMA Network. [cited 2016Apr13]. Retrieved from: http://archinte.jamanetwork.com/article.aspx?articleid=1898878

- ↑ Holpuch A. Elizabeth Warren asks CDC to consider legal marijuana as alternative painkiller [Internet]. The Guardian. Guardian News and Media; 2016 [cited 2016Apr13]. Retrieved from: http://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2016/feb/12/elizabeth-warren-medical-marijuana-painkiller-opioid-abuse

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCart Before the Horse - ↑ Cohen NL, Heinz AJ, Ilgen M, Bonn-Miller MO. Pain, cannabis species, and cannabis use disorders. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2016; 77:515–520.

- ↑ Richter L, Pugh BS, Ball SA. Assessing the risk of marijuana use disorder among adolescents and adults who use marijuana.Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;13:1–14.