Evidence-Based Practice in Tendinopathy

Introduction[edit | edit source]

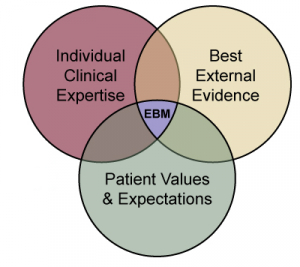

Evidence-based practice is about integrating the "best research evidence with clinical expertise and client preferences."[1] Applying an evidence-based practice approach to the management of tendinopathy is not as simple as applying one set of research findings from a single article in a recipe format for a patient.

Every patient presents with a unique clinical picture. The therapist managing the patient should apply a broad base of evidence to clinically reason a comprehensive management plan. This plan should be based on the best evidence available at that time. Evidence-based practice is fluid and constantly changes as more evidence is produced.

Tendinopathy[edit | edit source]

Painful conditions that emerge around or in tendons in response to overuse are called tendinopathies. In general, tendinopathies are complex and multifaceted. They are associated with pain, decreased function, and reduced exercise tolerance, and they can be difficult to treat.[2][3] They are delineated as non-rupture damage in the tendon, which is magnified with mechanical loading.[4]

For more information on key features of tendinopathy that can help with a differential diagnosis, please see: Differential Diagnosis of Tendinopathy.

The Challenge of Evidence-Based Practice in Tendons[edit | edit source]

There is a plethora of research available on tendons and tendinopathy, and it can be difficult to translate that evidence directly into clinical practice.

- In research settings, it is important to control as many variables as possible, so the results can be as accurate as possible.

- Researchers often only look at one parameter and measure that parameter over a specific period of time.

- It is impossible in a research setting to apply an entire rehabilitation programme as an intervention, and long-term follow-up is often difficult.

- Strong clinical reasoning skills are required to synthesise all the evidence available into clinically appropriate management strategies.

Tailor Protocols to the Individual[edit | edit source]

Every patient presents with a unique set of symptoms. It is the physiotherapist's responsibility to perform a thorough assessment and then clinically reason the assessment findings to get a complete clinical picture. Because research needs to be specific, research papers often cannot be directly applied to a patient. Concepts and aspects of protocols within papers need to be modified and tailored based on where the patient is at this point in their journey to recovery.[5]

It is important to always consider the person who is in front of you and to compare that to the demographics of the groups contained within a research paper. For example, is an intervention that worked for older men appropriate for younger females?

A 2015 study by Rio et al.[6] found that isometric exercises reduced pain in patellar tendinopathy. While this has promising applications for clinical practice,[6] the study was conducted on young athletic men with stringent exclusion criteria. Therefore, we need to be cautious when applying these findings to a more general population and also consider the importance of clinical experience in evidence-based practice (see Figure 1). Clinicians need to synthesise the best evidence available in research and adapt it to create a management plan that is appropriate for the patient in front of them. This plan must factor in the patient’s demographics and clinical findings.

Reading Outside of Tendon Literature[edit | edit source]

There are many aspects to treating a patient outside of the specific diagnosis. For individuals with tendinopathy, you must consider the person as a whole. It is useful to look more broadly at the literature on subjects such as communication, pain neuroscience, cross-education, and general strengthening. Synthesising all this information will help you to provide a holistically-informed evidence-based practice approach.

Consider Comorbidities[edit | edit source]

Tendinopathies do not occur in isolation. A person may present with a variety of comorbidities that can affect outcomes. When applying specific research protocols, it is important to factor in their comorbidities. For example:

- a patient with diabetes may not follow the standard trajectory of healing times

- a person with a systemic inflammatory condition such as rheumatoid arthritis may not respond as positively to a loading protocol

- while this is less common, symptomatic patellar tendinopathy can be associated with other conditions like connective tissue disorders (e.g. psoriatic arthritis, diabetes) and metabolic or autoimmune diseases.[7]

Patients should be screened during the assessment to rule out systemic comorbidities, especially when an increase in load does not form part of the clinical picture. A referral for medical management alongside physiotherapy is important for these patients.[7]

Consider Patient Preferences[edit | edit source]

We must also consider our patients' expectations and personal preferences when developing a management plan.

- Every person has different goals, and these should be incorporated into the treatment plan

- A patient-centred approach is important to ensure patient compliance as well as enhancing the therapeutic relationship[8]

Application of Tendon Research[edit | edit source]

Applying tendon research in clinical practice doesn't need to be complicated.

Our primary goal should always be to assess for function and functional deficits, as well as the patient's ideas, concerns and expectations. A patient-centred approach is always the best management strategy.[8]

- The research consistently shows that rehabilitation of tendinopathies should focus on slow, progressive loading.[9][10][11] The ideal exercise programme and prescription are still to be determined. People may respond in different ways to protocols based on their age, site of tendinopathy, activity levels and access to equipment.[9]

- Always consider the patient's individual goals and manage them according to where they are at that exact point in time. A 60-year-old sedentary woman with patellar tendinopathy will have very different goals and expectations than a 25-year-old professional volleyball player.

- Isolated training to rehabilitate a specific tendon or muscle group may be effective, but if a return to sport is the end goal, a much more comprehensive rehabilitation programme of the entire kinetic chain is required.[12][9]

General Summary of Evidence-Based Practice in Tendons[edit | edit source]

- Always consider a patient’s functional state

- Assess their current capacity as well as current goals and for a treatment plan based around them

- Slow progressive loading (tendons do not like fast changes)

- Consider the patient's current situation (e.g. are they in-season or out-of-season)

- Ensure you adopt a patient-centred approach - make sure that what you are giving them aligns with their values, beliefs, expectations and capacity

Additional Resources[edit | edit source]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Scurlock-Evans L, Upton P, Upton D. Evidence-based practice in physiotherapy: a systematic review of barriers, enablers and interventions. Physiotherapy. 2014 Sep 1;100(3):208-19.

- ↑ Millar NL, Silbernagel KG, Thorborg K, Kirwan PD, Galatz LM, Abrams GD et al. Tendinopathy. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2021 Jan 7;7(1):1.

- ↑ Challoumas D, Biddle M, Millar NL. Recent advances in tendinopathy. Faculty Reviews. 2020;9.

- ↑ Canosa-Carro, L., Bravo-Aguilar, M., Abuín-Porras, V., Almazán-Polo, J., García-Pérez-de-Sevilla, G., Rodríguez-Costa, I., López-López, D., Navarro-Flores, E. and Romero-Morales, C., 2022. Current understanding of the diagnosis and management of the tendinopathy: An update from the lab to the clinical practice. Disease-a-Month, 68(10), p.101314.

- ↑ Rio E. Evidence-Based Practice in Tendinopathy Course. Plus, 2020.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Ebonie Rio, Dawson Kidgell, Craig Purdam, Jamie Gaida, G Lorimer Moseley, Alan J Pearce, Jill Cook. Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med 2015;49:1277–1283.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Malliaras P, Cook J, Purdam C, Rio E. Patellar tendinopathy: clinical diagnosis, load management, and advice for challenging case presentations. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2015 Nov;45(11):887-98.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Fix GM, VanDeusen Lukas C, Bolton RE, Hill JN, Mueller N, LaVela SL, Bokhour BG. Patient‐centred care is a way of doing things: How healthcare employees conceptualize patient‐centred care. Health Expectations. 2018 Feb;21(1):300-7.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Cardoso TB, Pizzari T, Kinsella R, Hope D, Cook JL. Current trends in tendinopathy management. Best Practice & Research Clinical Rheumatology. 2019 Feb 1;33(1):122-40

- ↑ Muaidi QI. Rehabilitation of patellar tendinopathy. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2020;20(4):535-40.

- ↑ Mascaró A, Cos M, Antoni M, Roig A, Purdam C, Cook J. Load management in tendinopathy: Clinical progression for Achilles and patellar tendinopathy. Apunts. Medicina de l'Esport. 2018; 53:19-27.

- ↑ Abat F, Alfredson H, Cucchiarini M, Madry H, Marmotti A, Mouton C, Oliveira JM, Pereira H, Peretti GM, Romero-Rodriguez D, Spang C. Current trends in tendinopathy: consensus of the ESSKA basic science committee. Part I: biology, biomechanics, anatomy and an exercise-based approach. Journal of experimental orthopaedics. 2017 Dec;4(1):1-1.