Ependymoma

Original Editor - George Prudden

Shaimaa Eldib, Lucinda hampton, George Prudden, Kim Jackson, Vidya Acharya and Rewan Elsayed ElkanafanyDefinition:[edit | edit source]

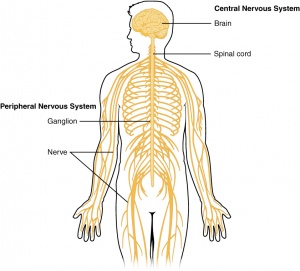

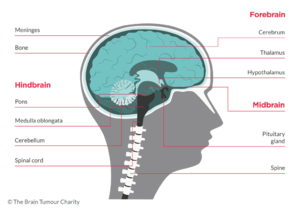

Ependymomas are tumors of the central nervous system (CNS), which means that they originate in either the brain or spine.They occur in both adults and children.However,ependymomas are considerd one of the commonest malignant brain tumor occurring in children. It account for approximately 10% of all such tumors. They have a predilection for young age at onset; indeed, over half of intracranial ependymomas arise in children under 5 years of age. There is slight male preponderance[1].As per the Central Brain Tumor Registry of the United States (CBTRUS) Statistical Report for CNS tumors from the years 2011 to 2015, ependymal tumors represent 1.7% of all brain and CNS tumors, with a median age of 44 years [2].Tumors of glial cells are the most common and are called gliomas.Tumors are classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Nervous System as grades I, II, and III based on their grade of anaplasia (cell disorganisation)[3]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy:[edit | edit source]

Glial cells :

Glial cells are a cell type that are found between nerve cells that share a general function of holding the CNS together. There are more glial cells than nerve cells and thereby constitute half of the total volume of the CNS. The four types of glial cells are: oligodenrocytes, microglia, epndymal cells and astrocytes.[4]

Ventricals:

Ventricals and the central canal of the spinal cord are fluid-filled spaces within the CNS that contain cerebrospinal fluid. Both are common locations for tumours.

Tentorium Cerebelli:

Tentorium Cerebelli is an extension of the dura matter that separates the cerebellum from the inferior aspect of the occipital lobes. Tumour below the tentorium are called infratentorial and those above are called supratentorial.

Pathological Process:[edit | edit source]

Ependymomas are traditionally thought to arise from oncogenetic events that transform normal ependymal cells into tumor phenotypes. The precise nature and order of these genetic events are unknown.[5]

Incidence[edit | edit source]

Children:[edit | edit source]

- The 3rd most common pediatric CNS tumour.[6]

- It represents around 6% to 12% of children brain tumor and 2% of all childhood cancer[6].

- The prognosis for pediatric ependymomas remains relatively poor when compared with other brain tumors in children,despite advances in neurosurgery, neuroimaging techniques, and postoperative adjuvant therapy.[6]

- The 5-year survival rate ranges from 39% to 64%.[6]

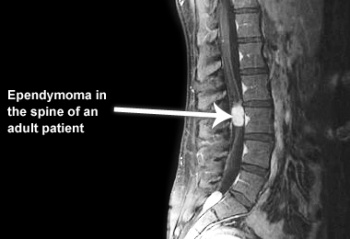

Adults:[edit | edit source]

- the most common primary glial neoplasm of spinal cord representing 50%–60% of all intramedullary cord neoplasms.[7][8]

- Most commonly occur in the spinal cord[3]

- Ependymomas are believed to be slow-growing tumors and exhibit benign pathology behavior[7].

Clinical Presentation:[edit | edit source]

Brain tumor symptoms include:[edit | edit source]

- Headache or pressure in the head

- Nausea or vomiting

- Blurred vision

- Weakness or numbness and tingling

Spinal cord symptoms include:[edit | edit source]

- Back pain

- Weakness in the arms or legs

- Numbness or tingling in the arms, legs or trunk

- Problems going to the bathroom or controlling bowel or bladder function[3][9]

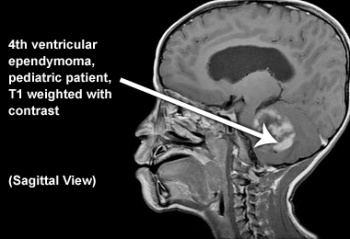

Diagnostic Procedures:[edit | edit source]

The diagnosis and disease staging is performed by craniospinal MRI. Tumor classification is achieved by histological and molecular diagnostic assessment of tissue specimens according to the World Health Organization (WHO) classification 2016. [10]

If the MRI confirms a primary tumour, patients normally do not need other imaging tests of the blood because ependymoma tumours do not tend to spread outside of the CNS. MRI scans provide a baseline so as to measure disease progression as well as identifying areas that have been affected.[3]

Tumours are classified and graded according to their appearance when viewed through the microscope follow the collection of cells from biopsy.A recent molecular classification has distinguished 9 subgroups of ependymal tumors that appear to reflect more precisely than histology alone the biological, clinical, and histopathological heterogeneity across the major anatomical compartments, age groups, and tumor grades[null .]Each of the 9 molecular subgroups is characterized by distinct DNA methylation profiles and associated genetic alterations[10][11].

World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Nervous System:[edit | edit source]

Myxopapillary ependymoma (WHO grade I)[edit | edit source]

This entity is characterised by cuboidal tumour cells, with GFAP expression and lack of cytokeratin expression, surrounding blood vessels in a mucoid matrix. Mitotic activity is very low or absent.

Subependymoma (WHO grade I)[edit | edit source]

Subependymoma has isomorphic nuclei in an abundant and dense fibrillary matrix with frequent microcysts; mitoses are very rare or absent.

Ependymoma (WHO grade II)[edit | edit source]

This neoplasm has moderate cellularity; mitoses are rare or absent and nuclear morphology is monomorphic. Key histological features are perivascular pseudorosettes and ependymal rosettes. Four histological variants have been described: cellular ependymoma, which has hypercellularity and increased mitotic rate, papillary ependymoma, clear cell ependymoma and tanycytic ependymoma.

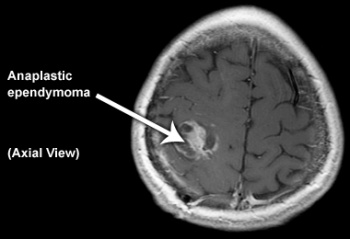

Anaplastic ependymoma (WHO grade III)[edit | edit source]

This tumour is characterised by hypercellularity, cellular and nuclear pleomorphism, frequent mitosis, pseudopalisading necrosis and endothelial proliferation. The latter two criteria do not appear to be independently related to prognosis. Perivascular rosettes are a histological hallmark.[12]

Management:[edit | edit source]

Many factors impact decisions about the treatment of ependymoma including the tumor location and grade, and the age of the person. Children and adults tolerate treatments differently, for that reason treatment for adults and treatment for pediatric patients may be very different.[3]

Surgery[edit | edit source]

When possible, removing the tumour from the brain or spinal cord is a priority as SCI associated with spinal tumor is often managed surgically[13]. A secondary goal of surgery is obtaining a biopsy of cancerous cells for diagnosis.

Radiation Treatment[edit | edit source]

External beam radiation treatment is commonly used to treat ependymoma. Beams of X-rays, gamma rays or protons are aimed at the area of head or spine where the tumour is located. The treatment aims to kill cancer cell and shrink tumours. The treatments last several weeks.

There are several methods of delivering radiation treatment:

- Conformal radiotherapy

- Intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT)

- Proton beam radiotherapy

- Stereotactic radiosurgery (SRS)

Chemotherapy[edit | edit source]

Chemotherapy is drug treatment for cancers or tumors. There are many types of drugs used to treat cancer. Traditionally cytotoxic agents designed to kill growing tumor cells are used.

These agents often have side effects such as hair loss, nausea and vomiting and can cause a decrease in blood counts.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

- Astrocytoma

- Choroid Plexus Papilloma

- Glioblastoma Multiforme

- Tumors of the Conus and Cauda Equina

- Vascular Surgery for Arteriovenous Malformations[5]

Key Evidence[edit | edit source]

- The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary.[14]

- Biology and management of ependymomas,[15]

- Ependymoma.[16]

- Neurofibromatosis type 2 service delivery in England.[17]

- Interdisciplinary management of hemicorporectomy after spinal cord injury.[18]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Swaiman KF, Ashwal S, Ferriero DM, Schor NF, Finkel RS, Gropman AL, Pearl PL, Shevell M. Swaiman's Pediatric Neurology E-Book: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017 Sep 21.

- ↑ Ostrom QT, Gittleman H, Truitt G, Boscia A, Kruchko C, Barnholtz-Sloan JS. CBTRUS statistical report: primary brain and other central nervous system tumors diagnosed in the United States in 2011–2015. Neuro-oncology. 2018 Oct 1;20(suppl_4):iv1-86.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Cern-foundation.org. (2017). Ependymoma Basics | CERN Foundation. [online] Available at: http://www.cern-foundation.org/education/ependymoma-basics [Accessed 24 Aug. 2017].

- ↑ Palastanga, N., Field, D. and Soames, R. (2012). Anatomy and Human Movement: Structure and Function. 6th ed. Burlington: Elsevier Science.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Emedicine.medscape.com. (2017). Ependymoma: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology. [online] Available at: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/277621-overview [Accessed 30 Aug. 2017].

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Kilday JP, Rahman R, Dyer S, Ridley L, Lowe J, Coyle B, Grundy R. Pediatric ependymoma: biological perspectives. Molecular Cancer Research. 2009 Jun 1;7(6):765-86.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Helseth A, Mørk SJ. Primary intraspinal neoplasms in Norway, 1955 to 1986: a population-based survey of 467 patients. Journal of neurosurgery. 1989 Dec 1;71(6):842-5

- ↑ Mohammed W, Farrell M, Bolger C. Spinal cord ependymoma–Surgical management and outcome. Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice. 2019 Apr 1;10(2):316.

- ↑ Sofuoğlu ÖE, Abdallah A. Pediatric Spinal Ependymomas. Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2018;24:7072.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Rudà R, Reifenberger G, Frappaz D, Pfister SM, Laprie A, Santarius T, Roth P, Tonn JC, Soffietti R, Weller M, Moyal EC. EANO guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of ependymal tumors. Neuro-oncology. 2017 Nov 29;20(4):445-56.

- ↑ Pajtler KW, Witt H, Sill M, Jones DT, Hovestadt V, Kratochwil F, Wani K, Tatevossian R, Punchihewa C, Johann P, Reimand J. Molecular classification of ependymal tumors across all CNS compartments, histopathological grades, and age groups. Cancer cell. 2015 May 11;27(5):728-43.

- ↑ Reni, M., Gatta, G., Mazza, E. and Vecht, C. (2007). Ependymoma. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology, 63(1), pp.81-89.

- ↑ Ge L, Arul K, Mesfin A. Spinal Cord Injury From Spinal Tumors: Prevalence, Management, and Outcomes. World neurosurgery. 2019 Feb 1;122:e1551-6.

- ↑ Louis DN, Perry A, Reifenberger G, von Deimling A, Figarella-Branger D, Cavenee WK, Ohgaki H, Wiestler OD, Kleihues P, Ellison DW. The 2016 World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System: a summary. Acta Neuropathol. 2016 Jun;131(6):803-20. doi: 10.1007/s00401-016-1545-1. Epub 2016 May 9. Review. PubMed PMID: 27157931.

- ↑ Wu J, Armstrong TS, Gilbert MR. Biology and management of ependymomas. Neuro Oncol. 2016 Jul;18(7):902-13. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/now016. Epub 2016 Mar 28. Review. PubMed PMID: 27022130; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC4896548.

- ↑ Reni M, Gatta G, Mazza E, Vecht C. Ependymoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2007 Jul;63(1):81-9. Epub 2007 May 4. Review. PubMed PMID: 17482475.

- ↑ Lloyd SK, Evans DG. Neurofibromatosis type 2 service delivery in England. Neurochirurgie. 2016 Jan 27. pii: S0028-3770(15)00279-9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuchi.2015.10.006. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID: 26826883.

- ↑ Tuel SM, Cross LL, Meythaler JM, Faisant TE, Krajnik SR, Hogan P, Sewell L, Wilson B, Rodwell DW, Smith J. Interdisciplinary management of hemicorporectomy after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992 Jul;73(7):669-73. PubMed PMID: 1622324.