Diastasis Recti Abdominis

Original Editor - Marianne Ryan

Top Contributors - Nicole Hills, Sivapriya Ramakrishnan, Lucinda hampton, Admin, Vidya Acharya, Victoria Geropoulos, Regan Haley, Rachael Lowe, Laura Ritchie, Marianne Ryan, Oyemi Sillo, Kim Jackson, Michelle Walsh, WikiSysop, Tarina van der Stockt and Claire Knott

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Diastasis recti abdominis (DRA) is an impairment characterized by an increase in midline separation of the rectus abdominis muscles due to the widening and thinning of the linea alba (LA).[2][3] This separation results in an increase in the distance between the two rectus abdominis muscles, commonly referred to as the inter-rectus distance (IRD).[3] DRA is present when the IRD increases and exceeds normal values,[4] which can be measured at 1 or more regions along the LA.[5] It should be noted, that the increase in midline “separation” of the rectus abdominis muscles involves stretching of the LA rather than a true separation.[6] DRA can occur in both males and females as well as across all age groups.[7] In infants, the separation between the rectus abdominis muscles can be congenital due to an abnormal alignment of fibre orientation within the LA or can occur as a result of decreased abdominal muscle activity.[7] In men, increasing age, significant weight fluctuations, weightlifting causing excessive increases in intraabdominal pressure (IAP), and/or inherited muscle weakness are all considered risk factors for the development of DRA.[8] DRA is most commonly recognized as a condition that is highly prevalent in pregnant and postpartum women,[2] which can be explained by the expansion of the uterus to accommodate the growing fetus.[7] The expanding uterus causes the rectus abdominis muscles to elongate while altering their angle of attachment, which in conjunction with hormonal elastic changes of connective tissue,[9] leads to the stretching of the LA resulting in an increased IRD, displacement of the abdominal organs, and a bulging of the abdominal wall.[7] During pregnancy, 33% of women present with an increased IRD by the second trimester,[10] and 100% of these women present with an increased IRD by the end of the third trimester.[11]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

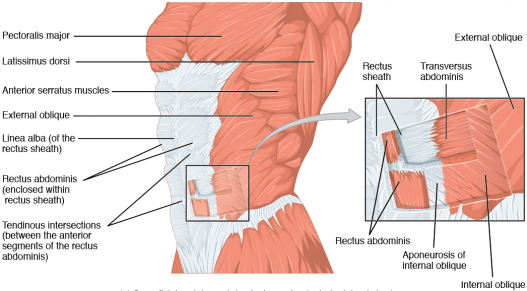

The anterior abdominal wall is supported by symmetrically aligned muscles on either side of the midline called the rectus abdominis muscles, which are composed of parallel muscle fibres. The external abdominal oblique, internal abdominal oblique, and transverse abdominis (TrA) obliques are flat muscles that can be found on the anterolateral aspect of the abdominal wall arranged from superficial to deep, with muscle fibres running obliquely and perpendicular, respectively.[7] White, fibrous tissue called aponeuroses run from the lateral abdominal wall to the midline, where it fuses to form the rectus sheaths encompassing the rectus abdominis muscles.[7] The two rectus abdominis muscle bellies run parallel to each other and are separated by connective tissue[12] from the rectus sheaths that are composed of highly organized collagen fibres and make up the LA) which runs horizontally from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis.[5] The distance between the two rectus abdominis muscles is commonly referred to as the IRD)[5]

The abdominal wall plays an important role in posture, trunk and pelvic stability and movement, respiration, and provides support to abdominal viscera.[3] An increase in IRD, such as that seen in DRA, can jeopardize the function of the abdominal wall and the rectus abdominis muscles, resulting in weakness and decreased stability and control.[13] When the abdominal wall musculature, the rectus sheath, or the LA is distorted, functional limitations may arise.[3]

The lumbar multifidus is a deep muscle and an important stabilizer of the lumbar spine. Its principal action is to extend the lumbar spine to balance the flexion forces generated by the anterior and anterolateral abdominal muscles to reinforce stabilization[14].

Due to pregnancy’s impact on the pelvic floor’s structure and function,[15] pelvic floor anatomy should be comprehensively understood when treating patients from the pregnant and postpartum populations. Because DRA occurs primarily in women during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy as well as throughout postpartum recovery, therapists who manage pregnancy-related DRA should be able to adequately assess the pelvic floor structures and its function in order to provide comprehensive care to patients. Based on the Delphi study by Dufour and colleagues (2019), impairments to the LA should be assessed as “an integrative component of the thoracopelvic abdominal system”.[2] Women’s health experts have “come to understand that the impairments and dysfunctions related to DRA [are] multidimensional and multifactorial”[2] and require individualized assessments in order to determine the extent of DRA’s impact on physical function.

The diaphragm is a dome-shaped structure that stretches from the xiphoid process of the sternum down to the pelvic floor and expands laterally to the internal surface of the 6 most inferior ribs. It is a thin, musculotendinous structure composed of two regions – the crural region and the costal region. The crural region of the diaphragm is responsible for breathing, while the costal region prevents gastroesophageal reflux. There is a significant connection and correlation between the respiratory and pelvic diaphragms that is worth noting with regards to DRA.[16] During normal respiration, or any physiologic diaphragmatic action, such as coughing, laughing, or sneezing, the pelvic floor diaphragm will exhibit a symmetric change to match that of the respiratory diaphragm. As the respiratory diaphragm descends during inspiration, the pelvic diaphragm will lower as well. This is to ensure control over IAP, to maintain stability of the trunk, and to maintain urinary continence. Respiratory function is not only controlled by the respiratory diaphragm, but the pelvic diaphragm as well. Conversely, although the pelvic diaphragm plays a significant role in supporting the pelvic organs and controlling IAP, it also functions to support respiratory function.[17] This will be particularly important to understand when working with women during pregnancy and in the postpartum phase as the diaphragm is displaced during pregnancy.[18] Furthermore, breathing techniques are commonly prescribed treatments to optimize abdominal, diaphragmatic, and pelvic floor function in postpartum women with DRA.[2]

Diastasis Recti Abdominis and Pregnancy[edit | edit source]

During pregnancy, the LA softens due to hormones and the mechanical stretch resulting from the accommodation of the growing fetus.[19] Because of this, there will be a progressive increase in the width of the linea alba (or IRD) throughout the trimesters, with the highest incidence occurring in the third trimester.[19]

A recent study by da Mota and colleagues (2015)[11] which studied 84 first-time pregnant women, found that 100% of these women had DRA by gestational week 35 when using a diagnostic criterion of 1.6cm at 2cm below the umbilicus. The prevalence decreased to 52.4% at 4-6 weeks postpartum and continued to decrease to 39% at 6 months.[11] While this agrees with other studies that have also found a decreased prevalence at 4 weeks[20][21] and 8 weeks postpartum,[19] a study by Coldron and colleagues (2008)[22] found that healing reached a plateau at 8 weeks postpartum and that IRD and rectus abdominis thickness and width did not return to the control values one year later.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

An adult is considered to have DRA when they present with an increased IRD, characterized by an observable and palpable separation between the two bellies of the rectus abdominis muscle.[23]

Currently, there is no consensus among the literature regarding the measurement criteria and diagnostic IRD cut-off value for DRA.[24] A study by Beer and colleagues (2009) suggests that, in nulliparous women (women who have not given birth), the normal width of the linea alba should be less than 1.5 cm at the xiphoid level, less than 2.2 cm at 3 cm above the umbilicus, and less than 1.6 cm at 2 cm below the umbilicus.[4]

However, when applying these values to clinical practice it is important to consider that the IRD values observed in primiparous women (or women who have given birth for the first time) may be seen as “normal” at wider values than nulliparous women.[25] A more recent study by Mota and colleagues suggests that the linea alba is considered normal up to 2.1 cm at 2 cm below the umbilicus, to 2.8 cm at 2 cm above the umbilicus and to 2.4 cm at 5 cm above the umbilicus at 6 months post-partum in primiparous women.[25]

To gain a more comprehensive understanding during physical assessment, a consensus study by Dufour and colleagues (2019) suggests that IRD should not be the only measure assessed when diagnosing DRA.[2] Clinicians should assess the anatomical and functional characteristics of the linea alba.[2] This includes palpating for tension during active contraction of linea alba[2], as well as during co-contraction of the pelvic floor muscles and the transverse abdominis.[5] As well, since larger IRDs have been found to be correlated with poorer trunk control[26], strength and endurance of the abdominal muscles should also be considered during assessment.[2]

Diagnostic Methods[edit | edit source]

The most traditionally used diagnostic method in clinical practice is the finger – width method, which primarily functions as a screening tool.[27] This tool is used to detect the presence or absence of DRA. If on palpation, the therapist can place two or more finger breaths (≈2cm) in the sulcus between the medial borders of the rectus abdominis muscles, the patient may present with diastasis recti abdominis.[28]

In terms of measuring IRD, ultrasound imaging (USI) has been titled the gold-standard method to measure IRD non-invasively[9], displaying good inter-rater [23] and intra-rater reliability in the literature. [25] However, its daily clinical use may be limited due to cost, availability, and training.[27] A more clinically feasible alternative is the use of calipers, whereby the tips of calipers are fitted across the width of the separation.[27] Calipers are considered to be reliable tool for measures of IRD at and above the umbilicus.[27] This was supported by Chiarello and McAuley (2013), who found that IRD measures with calipers were similar to those taken with USI above the umbilicus[29], however, additional research is need to evaluate the potential of calipers relative to ultrasound imaging.[27]Other alternatives include computed tomography (CT scan) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which are considered the method of choice when assessing the abdominal wall, however, both are not clinically feasible and are expensive.[27]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

Our abdominal muscles play an important role in postural control, trunk and pelvic stability, trunk movement and respiration.[31] A study by Gilleard and Brown (1996) reported that the structural changes that occur to the abdominal muscles during pregnancy can limit abdominal muscle function, decreasing the ability of the abdominals to provide stability to the pelvis against resistance during pregnancy and up to 8 weeks postpartum.[20] In support of this, a study by Liaw and colleagues suggested that the size of IRD was negatively associated with abdominal muscle function.[13] Additionally, a more recent study by Hills and colleagues (2018) determined that women with DRA had a lower capacity to generate trunk rotation torque and perform sit-ups.[26] This was supported by a negative correlation between IRD and trunk rotation peak torque generating capacity and sit-up test scores.[26]

Some studies have implicated weak abdominal muscles in causing abdominal[32] and lumbo-pelvic pain and dysfunction during pregnancy.[33] [34]There is some evidence to support the idea that an increased inter-rectus distance is associated with the severity of self-reported abdominal pain.[35] Additionally, it has also been hypothesized that weak abdominal muscles can result in ineffective pelvic floor muscle (PFM) contraction.[33] However, the evidence doesn’t fully support this as da Mota and colleagues (2015)[11] and Sperstad and colleagues (2016)[10] found no link between DRA and lumbopelvic pain. Bø and colleagues (2017)[36] also found no link between DRA and weakness of pelvic floor musculature or prevalence of urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse.

While the condition is very common, there is a lack of high-quality evidence to guide management in clinical practice. This creates debate when it comes to carrying out a conservative care approach. [2] However, Dufour and colleagues (2019)[2] interviewed credentialed women’s health physiotherapists to create 28 Canadian expert-based recommendations for the assessment and management of DRA. The consensus revealed that the presentation of women with DRA is multidimensional and there is a need for an individualized care approach for each client.[2]

Beginning exercises prenatally may help to maintain the tone and control over abdominal musculature to decrease some stress of the linea alba.[37] Early literature suggests that functional capacity of abdominal musculature may be compromised due to a change in the muscle’s line of action.[20] Since then, Chiarello and colleagues (2005)[38] found that the occurrence and size of DRA is greater in pregnant women who do not exercise and that, since the abdominals play an important functional role in exercise, women must be screened for the presence of DRA. More recent evidence supports deep core stability-strengthening 3 times a week for 8 weeks, in addition to bracing, to improve inter-recti separation and quality of life as measured by the Physical Functioning Scale (PF10).[39] The exercises included diaphragmatic breathing, pelvic floor contraction, plank, isometric abdominal contractions, and traditional abdominal exercises.[39] Lee and Hodges (2016)[5] proposed that narrowing the IRD may not be optimal and that pre-activation of TrA can increase the tension and decrease the distortion of the linea alba, which will allow for the force to be transmitted across the midline. However, Gluppe and colleagues (2018)[40] found that a supervised exercise class once a week for 16 weeks, in addition to daily home training, did not reduce the prevalence of DRA at 6 months postpartum. The exercises focused on strengthening the pelvic floor, but also relaxation and stretching, as well as strengthening of the abdominals, back, arms, and thighs.[40]

Patient Education[edit | edit source]

It is important to educate our patients on diastasis recti abdominis during and after pregnancy in order to manage patient expectations, limit fear and anxiety, and best prepare our patients for the pregnancy and birth-related changes their bodies will experience. Mota and colleagues (2015) have suggested that 100% of women will exhibit an increased IRD in the third trimester,[11] characterized as DRA. This statistic, as well as DRA language such as “gap” and “separation”, can be extremely fear-inducing and has the potential of increasing stress and anxiety in our patients, which can have negative physiological and psychological effects on both mom and baby.[41] Therefore, it is important to remind patients that are trying to get pregnant, and those who already are, that women’s bodies have been designed to grow and expand in order to accommodate a growing fetus. Hormonal changes in pregnancy result in increased laxity and softening of connective tissue,[9] resulting in the widening of the LA to create space for the baby. Not only is this process a natural part of pregnancy, it is also necessary in order for the baby to have adequate room to grow.

In the postpartum phase, patients and PT’s will often direct focus to the management of DRA in order to optimize function. The definition of DRA describes a pathological increase in the distance between the two rectus abdominis muscles, or an increase in the IRD, due to a stretching, thinning, and/or widening of the LA. Therefore, decreasing the IRD appears to be the most obvious rehabilitation objective or management strategy,[5] and is widely supported by clinicians based on the assumption that restoring the alignment of the rectus abdominis muscles, by decreasing the IRD, will also restore the function of these muscles.[42] However, Lee and Hodges (2016) suggest that LA tension, as opposed to a decrease in IRD, may be more important to support abdominal contents and to effectively transfer force between opposing abdominal muscles.[5] In patients with DRA, the LA is distorted and slackened (reduction of tension), when the IRD is reduced. Reducing LA tension could result in a bulging or distorted LA while pre-activation of the TrA before the rectus abdominis muscles results in an increase in IRD but also an increase in LA tension.[5] It is important to educate patients on the potential that increasing LA tension could be a more effective management and rehabilitation plan than closing the “gap” and decreasing the IRD as it “is unlikely to optimally support the abdominal contents (potentially producing less desirable cosmetic appearance), and could induce less effective mechanical function”.[5]

The video below by a Canadian physiotherapist uses a great analogy to explain the concept of diastasis recti abdominis.

Cosmetic appearance can be affected by DRA due to extension and loss of tension of the LA causing a bulging of the abdominal wall.[7] This bulging, “tenting”, or “coning” is commonly referred to as “mummy tummy” and can be seen when women are going from lying down to sitting, when exercising, or even at rest. An increased IRD is positively associated with worse body image in women with DRA, and therefore, it may be indicated to include body image and body satisfaction outcome measures and management when treating pregnant and postpartum women with DRA.[44]

There is a growing consensus suggesting that DRA is not necessarily a condition physiotherapists and patients need to prevent and treat, but in fact a very normal part of pregnancy that women’s bodies are naturally designed to do to create space for the growing baby. However, there are multiple techniques physiotherapists can prescribe to their pregnant and postpartum patients to help maintain and optimize strength and function. Pelvic floor physiotherapists are qualified to develop exercise and movement strategies that are warranted “to promote optimal physical function through the pregnancy, limit potential functional impairment and prepare for birth” and manage postpartum recovery.[2] Furthermore, it is crucial for physiotherapists to discuss patient concerns, expectations, and goals in order to create individualized and targeted management and treatment plans. Individualized rehabilitation for DRA and any postpartum concerns is a necessity,[5] and taking a full and well-round subjective history and asking questions about expected outcomes and goals, can help physiotherapists create individualized management and rehabilitation plans for each patient.

Common Postpartum Exercises[edit | edit source]

Exercises for the Inner Unit:[edit | edit source]

The consensus study conducted by Dufour and colleagues (2019) emphasized the use of inner unit exercises during the prenatal, early postpartum and late postpartum periods for the management of DRA.[2]This is consistent with a study by Mesquita and colleagues (1999), who suggested inner unit exercises should be performed immediately post-delivery.[45] Similarly, a more recent study by Thabet and Alshehri (2019) concluded that a deep core stability exercise program (i.e. diaphragmatic breathing, pelvic floor contraction, plank and isometric abdominal contraction) was effective in treating DRA and improving quality of life postpartum.[39]

The inner unit muscles, which include the transverse abdominis, multifidus, diaphragm and pelvic floor muscles, provide stabilization to the core. When commencing inner unit exercises, emphasis should first be placed on achieving controlled isolation of each muscle in the unit, followed by controlled co-activation of the inner unit.[2] While trying to achieve control of the inner unit in the prenatal, early postpartum and late postpartum periods, it is important to remember that exercises that engage the superficial abdominal muscles should be avoided (i.e. sit-ups).[2] Once isolation of the inner unit is achieved, exercises should be progressed to include the outer unit, as well as, exercises that are more functionally based.[2]

Transverse Abdominis (TA):

First, have the individual position themselves in supine crook-lying or in side-lying with a neutral spine. Once in the proper position, instruct the patient to palpate their TA muscle using their index and middle fingers just medial to their front pelvic bones (or ASIS).[46] Following this, have the individual draw in their abdomen and contract their TA muscle while preforming relaxed breathing. The following cues can be used to isolate the transverse abdominis: “imagine you are pulling your pelvic bones together in a straight line” or “bring your belly button towards your spine”.[46] The individual should hold the contraction for 3-5 seconds while they exhale and relax their TA as they inhale.[46] The individual can perform 3 sets of 10 repetitions, 3-4 times per week.[46] Ensure there is no compensatory strategies such as posterior tilting of the pelvis, depression of the ribcage, breath-holding or bulging of the abdomen.[46]

Multifidus:

With the individual positioned in supine or side-lying with a neutral spine, have them imagine a line that connects their left and right sides of their posterior pelvis.[46] Next, tell the individual to contract their multifidus to try draw together their left and right halves along this line.[46] The individual should practice relaxed breathing, ensuring to recruit their multifidus during exhalation. The contraction should be held for 3-5 seconds, 3 sets of 10, 3-4 times per week.[46] No anterior tilting of the pelvis, flexion of the hips and movement of the thorax and lower back should be observed.[46]

Pelvic Floor Muscle (PFM):

In supine crook-lying or side-lying, instruct the individual to imagine closing off their urethra as if they are trying to stop the flow of urine.[46] Alternatively, have the individual imagine that they are lifting their anus up towards their pubic bone.[46] As suggested by Diane Lee (2019), an alternative position for isolating the PFM is to sit on a small, softball as the ball can help provide feedback to your brain.[46] The individual should inhale while contracting their PFMs, ensuring to expand their front, back and sides of their lower rib cage.[46] During exhalation, the individual should relax their pelvic floor. The contraction should be held for 3-5 seconds, 3 sets of 10, 3-4 times per week.[46] While performing this exercise, the individual should not feel any tension in their abdomen and should not feel their buttocks tighten or movement in their spine. [46]

Diaphragm:

During pregnancy, the diaphragm is displaced upwards approx. 5 cm to accommodate for the increasing size of the uterus.[18] As a result, the work placed on the diaphragm increases and compensatory strategies such as increased accessory muscle recruitment are adopted. [18]

Given the changes to the diaphragm during pregnancy, it is recommended that during the prenatal, early post-partum and late-postpartum periods, a tension-free diaphragmatic breathing pattern should be adopted.[2] This means that during inhalation, the diaphragm should descend downward and the lateral costal rib cage should expand outward.[2]

To facilitate this breathing pattern, the following breathing exercises can be practiced:

- Diaphragmatic Breathing: Position the individual in a supine position with their knees bent. A pillow can be placed under the knees for support. Have the individual place one hand on their chest and one hand over the apex (highest point) of the abdomen. Instruct the individual to breathe into their hand with short, shallow breaths. The individual should only feel their hand rise at their abdomen and not at their chest. Encourage inhalation through the nose and exhalation through the mouth. Alternatively, instructing the individual to “sniff” into their hand on their abdomen is a cue that can be used to encourage diaphragmatic breathing. The individual can practice this technique 5-10 minutes at a time, 1-4 times per day, gradually building up their tolerance.[47]

- Lateral Costal Breathing: Position the individual in a supine position with their knees bent. A pillow can be placed under the knees for support. Have the individual place their hands on the sides of their ribcage. Instruct the individual to take a deep breath through their nose and expand their ribcage into their hands. After inhalation, have the individual exhale slowly through their mouth. The individual can practice this technique 5-10 minutes at a time, 1-4x/ day, gradually building up their tolerance.

Throughout postpartum recovery and pregnancy-related DRA management, Physiotherapists should encourage modifications to activities, as well as static and dynamic postures, to reduced repeated increases in IAP.[2] For example, rolling onto one side first prior to getting up out of bed, using a squatty potty to optimize the angle of the rectum and reduce straining.[50] Once isolated, controlled activation of each muscle of the inner unit is achieved, progressions can begin to focus on co-activation of the inner unit as well as more functionally oriented exercises[2] such as isometric contractions and rotational movements. Furthermore, postpartum patients should avoid high-impact exercises until 9-12months,[51] and should avoid all exercises in which the continence mechanism cannot be maintained.[2]

Body Mechanics[edit | edit source]

During the prenatal, intrapartum, early and late postpartum periods, it is important to avoid movements that create repeated increases in intra-abdominal pressure.[2] This recommendation is supported by the findings of Sperstad and colleagues whereby pregnant women who performed heavy lifting more than 20 times per week were at an increased risk of developing DRA.[10]

Education on posture and body mechanics should include aspects such as: lifting/carrying objects, rolling to the side to get up while using the arm to push up, straining on the toilet, maintenance of a neutral spine alignment with both dynamic and static postures and placement of one foot higher than the other when standing for prolonged periods of time.[2][52]

Commonly taught techniques:

- Bed Mobility: To get out of bed, the individual should first roll to their side and then push off the edge of the bed using their top arm.[53]

- Lifting: Whether it involves lifting a light object or heavy object, effective body mechanics should always be applied.[53] To do so, instruct the individual to get as close as possible to the object they are lifting.[53] The individual should inhale as they grasp onto the object while widening their stance with bent knees and a neutral spine.[53] To lift the object, the individual should straighten their knees while exhaling.[53] Lastly, the individual should ensure their spine is kept in neutral as they bend their knees to release the object onto its resting place.[53]

Postural Awareness[edit | edit source]

After pregnancy, some women tend to stand with and an exaggerated anterior pelvic tilt and with their pelvis pushed forward. In order to stand up against gravity, their bodies typically develop areas of rigidity in the upper lumbar and the lower thoracic area along with the buttock muscles. Diane Lee refers to this as “back clenching and buttock griping behaviour.” Manual therapy and relaxation exercises may be indicated before initiating strengthening exercises.http://dianelee.ca/articles/UnderstandYourBack&PGPopt.pdf

Abdominal Supports[edit | edit source]

Although researchers suggest that external support, such as abdominal binding, should not be recommended as a primary rehabilitation technique for DRA to avoid reliance, there may be benefits to its use, coupled with exercise, in specific cases.[2] For example, abdominal binding can provide additional support and comfort, and can help with cueing and proprioception for women in the early postpartum period and can increase patients’ confidence when attempting to activate or contract the abdominal muscles. A randomized control trial by Cheifetz and colleagues (2010), suggests that abdominal support is effective at managing distress and improving patients’ experience following a major abdominal surgery, which could be relevant for patients with DRA recovering from a caesarean delivery.[58]

Select clinical experts have suggested that non-elastic binders result in a greater likelihood of an increase in intravesical pressure (IVP)[51], or pressure of urine in the bladder.[59] Therefore, it is important to note that if abdominal binders are going to be prescribed or suggested, elastic binders are more likely to promote recovery than non-elastic binders.[51] Additionally, elastic wraps allow for greater movement and are less likely to restrict breathing.[51]

If an abdominal wrap or binding is going to be used, it should be initiated immediately postpartum and worn for support for approximately 8 weeks, or until the patient has the ability to generate tension in the inner unit during activity. External support should always be used in conjunction with inner unit activation and exercises to regain control and co-activation of the inner unit muscles. Additionally, abdominal bindings should always be wrapped from the bottom up to avoid an increase in pressure on the uterus and pelvic organs, which can cause downward descent or prolapse of the pelvic organs. The abdominal wrap should offer light compression or gentle hugging as too much compression can increase IAP.[51]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Wikimedia Commons.https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:1112_Muscles_of_the_Abdomen_Anterolateral.png (accessed 22 June 2018).

- ↑ 2.00 2.01 2.02 2.03 2.04 2.05 2.06 2.07 2.08 2.09 2.10 2.11 2.12 2.13 2.14 2.15 2.16 2.17 2.18 2.19 2.20 2.21 2.22 2.23 2.24 Dufour S, Bernard S, Murray-Davis B, Graham N. Establishing expert-based recommendations for the conservative management of pregnancy-related diastasis rectus abdominis: A Delphi consensus study. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2019 Apr 1;43(2):73-81.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Acharry N, Kutty RK. Abdominal Exercise With Bracing, A Therapeutic Efficacy In Reducing Diastasis-Recti Among Postpartal Females. International Journal of Physiotherapy and Research. 2015Nov;3(2):999–1005.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Beer GM, Schuster A, Seifert B, Manestar M, Mihic‐Probst D, Weber SA. The normal width of the linea alba in nulliparous women. Clinical anatomy. 2009 Sep;22(6):706-11.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 5.8 5.9 Lee D, Hodges PW. Behavior of the linea alba during a curl-up task in diastasis rectus abdominis: an observational study. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2016 Jul;46(7):580-9.

- ↑ Hickey F, Finch JG, Khanna A. A systematic review on the outcomes of correction of diastasis of the recti. Hernia. 2011;15(6):607–14.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 Michalska A, Rokita W, Wolder D, Pogorzelska J, Kaczmarczyk K. Diastasis recti abdominis — a review of treatment methods. Ginekologia Polska. 2018;89(2):97–101.

- ↑ Cheesborough JE, Dumanian GA. Simultaneous Prosthetic Mesh Abdominal Wall Reconstruction with Abdominoplasty for Ventral Hernia and Severe Rectus Diastasis Repairs. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2015;135(1):268–76.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Benjamin DR, Van de Water AT, Peiris CL. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014 Mar 1;100(1):1-8.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Sperstad JB, Tennfjord MK, Hilde G, Ellström-Engh M, Bø K. Diastasis recti abdominis during pregnancy and 12 months after childbirth: prevalence, risk factors and report of lumbopelvic pain. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jun 20:bjsports-2016.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Mota PG, Pascoal AG, Carita AI, Bø K. Prevalence and risk factors of diastasis recti abdominis from late pregnancy to 6 months postpartum, and relationship with lumbo-pelvic pain. Manual therapy. 2015 Feb 1;20(1):200-5.

- ↑ Peterson-Kendall F, Kendall-McCreary E, Geise-Provance P, McIntyre-Rodgers, Romani W. Muscles: Testing and Function, with Posture and Pain. 5th ed. Baltimore: Wolters Kluwer; 2005.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Liaw LJ, Hsu MJ, Liao CF, Liu MF, Hsu AT. The relationships between inter-recti distance measured by ultrasound imaging and abdominal muscle function in postpartum women: a 6-month follow-up study. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2011 Jun;41(6):435-43

- ↑ Macintosh JE, Bogduk N. The biomechanics of the lumbar multifidus. Clinical Biomechanics. 1986;1(4):205–13.

- ↑ Geelen HV, Ostergard D, Sand P. A review of the impact of pregnancy and childbirth on pelvic floor function as assessed by objective measurement techniques. International Urogynecology Journal. 2018;29(3):327–38.

- ↑ Bordoni B, Zanier. Anatomic connections of the diaphragm influence of respiration on the body system. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare. 2013;6:281-291.

- ↑ Talasz H, Kremser C, Kofler M, Kalchschmid E, Lechleitner M, Rudisch A. Phase-locked parallel movement of diaphragm and pelvic floor during breathing and coughing—a dynamic MRI investigation in healthy females. International Urogynecology Journal. 2010;22(1):61–8.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 LoMauro A, Aliverti A. Respiratory physiology of pregnancy: physiology masterclass. Breathe. 2015 Dec 1;11(4):297-301.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Boissonnault JS, Blaschak MJ. Incidence of diastasis recti abdominis during the childbearing year. Physical therapy. 1988 Jul 1;68(7):1082-6.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Gilleard WL, Brown JM. Structure and function of the abdominal muscles in primigravid subjects during pregnancy and the immediate postbirth period. Physical therapy. 1996 Jul 1;76(7):750-62.

- ↑ Hsia M, Jones S. Natural resolution of rectus abdominis diastasis. Two single case studies. Aust J Physiother. 2000 Jan 1;46(4):301-7.

- ↑ Coldron Y, Stokes MJ, Newham DJ, Cook K. Postpartum characteristics of rectus abdominis on ultrasound imaging. Manual therapy. 2008 Apr 1;13(2):112-21.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Keshwani N, Hills N, McLean L. Inter-rectus distance measurement using ultrasound imaging: does the rater matter?. Physiotherapy Canada. 2016;68(3):223-9.

- ↑ Mota P, Gil Pascoal A, Bo K. Diastasis recti abdominis in pregnancy and postpartum period. Risk factors, functional implications and resolution. Current Women's Health Reviews. 2015 Apr 1;11(1):59-67.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Mota P, Pascoal AG, Carita AI, Bø K. Normal width of the inter-recti distance in pregnant and postpartum primiparous women. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2018 Jun 1;35:34-7.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Hills NF, Graham RB, McLean L. Comparison of trunk muscle function between women with and without diastasis recti abdominis at 1 year postpartum. Physical therapy. 2018 Oct 1;98(10):891-901.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 27.3 27.4 27.5 Van de Water AT, Benjamin DR. Measurement methods to assess diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle (DRAM): a systematic review of their measurement properties and meta-analytic reliability generalisation. Manual therapy. 2016 Feb 1;21:41-53.

- ↑ Noble E. Essential Exercises for the Childbearing Year. 2nd edition. Boston, MA: Houghton Miffilin; 1982.

- ↑ Chiarello CM, McAuley JA. Concurrent validity of calipers and ultrasound imaging to measure interrecti distance. journal of orthopaedic & sports physical therapy. 2013 Jul;43(7):495-503.

- ↑ Learn with Diane Lee. Linea alba screen DRA with Diane Lee. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=06o8Z54l-40 [last accessed 22/06/2018]

- ↑ Benjamin DR, Van de Water AT, Peiris CL. Effects of exercise on diastasis of the rectus abdominis muscle in the antenatal and postnatal periods: a systematic review. Physiotherapy. 2014 Mar 1;100(1):1-8.

- ↑ Fast AV, Weiss L, Ducommun EJ, Medina EV, Butler JG. Low-back pain in pregnancy. Abdominal muscles, sit-up performance, and back pain. Spine. 1990 Jan;15(1):28-30.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Spitznagle TM, Leong FC, Van Dillen LR. Prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in a urogynecological patient population. International Urogynecology Journal. 2007 Mar 1;18(3):321-8.

- ↑ Parker MA, Millar LA, Dugan SA. Diastasis rectus abdominis and lumbo-pelvic pain and dysfunction-are they related?. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2009 Jul 1;33(2):15-22.

- ↑ Keshwani N, Mathur S, McLean L. Relationship between interrectus distance and symptom severity in women with diastasis recti abdominis in the early postpartum period. Physical therapy. 2018 Mar 1;98(3):182-90.

- ↑ Bø K, Hilde G, Tennfjord MK, Sperstad JB, Engh ME. Pelvic floor muscle function, pelvic floor dysfunction and diastasis recti abdominis: Prospective cohort study. Neurourology and urodynamics. 2017 Mar 1;36(3):716-21.

- ↑ Zappile-Lucis M. Quality of life measurements and physical therapy management of a female diagnosed with diastasis recti abdominis. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2009 Apr 1;33(1):22.

- ↑ Chiarello CM, Falzone LA, McCaslin KE, Patel MN, Ulery KR. The effects of an exercise program on diastasis recti abdominis in pregnant women. Journal of Women’s Health Physical Therapy. 2005 Apr 1;29(1):11-6.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 39.2 Thabet AA, Alshehri MA. Efficacy of deep core stability exercise program in postpartum women with diastasis recti abdominis: a randomised controlled trial. Journal of musculoskeletal & neuronal interactions. 2019;19(1):62.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Gluppe SL, Hilde G, Tennfjord MK, Engh ME, Bø K. Effect of a postpartum training program on the prevalence of diastasis recti abdominis in postpartum primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. Physical therapy. 2018 Apr 1;98(4):260-8.

- ↑ Glynn LM, Schetter CD, Hobel CJ, Sandman CA. Pattern of perceived stress and anxiety in pregnancy predicts preterm birth. Health Psychology. 2008;27(1):43–51.

- ↑ Oneal RM, Mulka JP, Shapiro P, Hing D, Cavaliere C. Wide Abdominal Rectus Plication Abdominoplasty for the Treatment of Chronic Intractable Low Back Pain. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2011;127(1):225–31.

- ↑ Phit Physiotherapy. DRA: Being (banana) split up the middle, a fresh (produce) perspective. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rVxAUOkb3M4[last accessed 22/06/2018]

- ↑ Keshwani N, Mathur S, Mclean L. Relationship Between Interrectus Distance and Symptom Severity in Women With Diastasis Recti Abdominis in the Early Postpartum Period. Physical Therapy. 2017 Apr;98(3):182–90.

- ↑ Mesquita LA, Machado AV, Andrade AV. Physiotherapy for reduction of diastasis of the recti abdominis muscles in the postpartum period. Revista Brasileira de Ginecologia e Obstetrícia. 1999 Jun 1;21(5):267-72.

- ↑ 46.00 46.01 46.02 46.03 46.04 46.05 46.06 46.07 46.08 46.09 46.10 46.11 46.12 46.13 46.14 Core training vs. strengthening: Core Training vs. Strengthening [Internet]. Diane Lee & Associates. 2019 [cited 2020Jun8]. Available from: https://dianeleephysio.com/education/core-training-vs-strengthening/

- ↑ Wong C. How to Do Belly Breathing Technique [Internet]. Verywell Health. Verywell Health; 2020 [cited 2020Jun8]. Available from: https://www.verywellhealth.com/how-to-breathe-with-your-belly-89853

- ↑ jivan sharma. Diaphragmatic Breathing Technique. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0Ua9bOsZTYg [last accessed 11/6/2020]

- ↑ BlueJay Mobile Health. Lateral Costal Breathing | Pelvic Physical Therapy. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SRj425_jark [last accessed 11/6/2020]

- ↑ Modi RM, Hinton A, Pinkhas D, Groce R, Meyer MM, Balasubramanian G, et al. Implementation of a Defecation Posture Modification Device. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology. 2019;53(3):216–9.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 Di Paolo J. Diastasis Rectus Abdominis: Moving the evidence to practice-based solutions. PowerPoint Presentation at: American Physical Therapy Association – Combined Sections Meeting; 2019 Jan 24; Washington, DC.

- ↑ Davis DC. The discomforts of pregnancy. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 1996 Jan;25(1):73-81.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 53.3 53.4 53.5 Correct Body Mechanics and Posture for Pregnancy [Internet]. Correct Body Mechanics and Posture for Pregnancy | Lovelace Health System in New Mexico. [cited 2020Jun11]. Available from: https://lovelace.com/news/blog/correct-body-mechanics-and-posture-pregnancy

- ↑ LovelaceHealthSystem. Body Mechanics & Posture for Pregnancy: Bed Mobility. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nibeN8lE6rk&feature=emb_logo [last accessed 11/6/2020]

- ↑ LovelaceHealthSystem. Body Mechanics & Posture for Pregnancy: Lifting. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9hePGxsC6nw&feature=emb_logo [last accessed 11/6/2020]

- ↑ Diane Lee's Integrated Systems Model for Physiotherapy in Womens' Health. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5oslM6Pe9AU&t=1844s [last accessed 22/6/2018]

- ↑ Diane Lee. Conference Presentations Diane Lee and Associates in Physiotherapy. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mHY6CSSosNE&t=10s[last accessed 22/6/2018]

- ↑ Cheifetz O, Lucy SD, Overend TJ, Crowe J. The Effect of Abdominal Support on Functional Outcomes in Patients Following Major Abdominal Surgery: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Physiotherapy Canada. 2010;62(3):242–53.

- ↑ Claridge M. Intravesical Pressure And Outflow Resistance During Micturition. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2009;42(S20):95–104.