Degenerative Disc Disease

Original Editor - Amanda E Davidson and Colby Boers, Lisa Pernet

Top Contributors - Lisa Pernet, Gaëlle Vertriest, Admin, Vanbeylen Antoine, Amanda E Davidson, Garima Gedamkar, Candace Goh, Laura Ritchie, Scott Cornish, Uchechukwu Chukwuemeka, Kim Jackson, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, De Maeght Kim, Lucinda hampton, Aya Alhindi and Eric Robertson

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Degenerative disc disease (DDD) is a process where the intervertebral discs lose height and hydration. When this occurs, the discs are unable to fulfill their primary functions of cushioning and providing mobility between the vertebrae. Although the exact cause of the disease is unknown, it is thought to be associated with the aging process during which the intervertebral discs dehydrate, lose elasticity, and collapse. Degenerative disc disease may develop at any level of the spine, but is most common in the cervical and lower lumbar regions.[1][2][3]

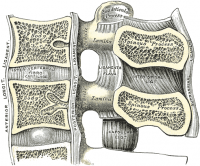

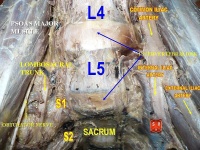

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Lumbar DDD is a condition that maybe a cause of lower back pain, which results from the co-existence of two different time scales, the slow dynamics of disc degeneration and the fast dynamics of pain recurrence. [4]

Lumbar DDD can also imply radiating pain from damaged discs in the spine. A lumbar spinal disc acts as a shock absorber between two vertebrae and allows the joints and the spine to move easily. The outer region of the disc, the annulus fibrosis, surrounds the soft inner core of the disc, the nucleus pulposus. Spinal discs undergo degenerative changes as we age, but not everyone will have symptoms as a result of these changes. Neural inflammation is one such possible cause of pain. When the outer section of the disc ruptures, the inner core can leak out, releasing proteins that irritate the neural tissue. Another cause is when discs can no longer absorb stress as well, leading to abnormal movement around the vertebral segment and causing back muscles to spasm as they try to stabilise the spine. In some cases the segment may collapse, causing nerve root compression and radiculopathy. Pain often reduces with time as the inflammatory proteins dissipate and the disc collapse settles into a stable position. [5]

Intervertebral Discs

Dengenerative Disc Disease is thought to begin with changes to the annulus fibrosis, intervertebral disc, and subchondral bone. The process of degeneration is divided into three classifications: early dysfunction, intermediate instability, and final stabilisation.

- Early dysfunction is the start of degenerative changes which can occur as early as 20 years old.

- Intermediate instability is classified by a loosening of the annulus fibrosis, which can cause lower back pain.

- Final stabilisation is where fibrosis develops in the posterior structures and osteophytes form. Pain and motion both decrease. [6]

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

Degenerative disc disease is fairly common and it is estimated that at least 30% of people aged 30-50 years old will have some degree of disc space degeneration, although not all will have pain or ever receive a formal diagnosis.[7] The pain is frequently caused by simple wear and tear as part of the general ageing process. It can also be as a result of a twisting injury to the lower back.

The process that leads to DDD begins with structural changes. The annulus fibrosis loses water content over time which makes it increasingly unyielding toward the daily stresses and strains placed on the spine. The loss of compliance in the discs contributes to forces being redirected from the anterior and middle portions of the facets to the posterior aspect, causing facet arthritis. Hypertrophy of the vertebral bodies adjacent to the degenerating disc also results. These overgrowths are known as bony spurs or osteophytes.

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

| [8] |

DDD commonly occurs with other diagnoses such as:

- idiopathic low-back pain

- lumbar radiculopathy

- myelopathy

- lumbar stenosis

- spondylosis[3][3][3][3][3][3][3][3]

- osteoarthritis

- zygapophydeal joint degeneration [6]

Activities that typically increase pain include:

- Sitting for extended periods of time

- Rotating, bending, or lifting

Activities that typically decrease pain include:

- Frequent changes in positions

- Lying down

- Staying active [9]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

People with DDD will often present with low back pain[8] with varying levels of severity between individuals. Pain is often chronic, but can also be acute on chronic with varying episodes of exacerbation [9]

There are different degrees of annular disruption[1] which are classified into 5 grades. These grades are differentiated by means of a contrast medium injection.

- Grade 0: no disruption

- Grade 1: the contrast medium passes into the cartilage endplate through a tear

- Grade 2: the contrast medium flows into the bony endplate

- Grade 3: the contrast medium enters into the cancellous bone of vertebra under endplate

- Grade 4: the contrast medium leaks completely in the cancellous bone.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Provocation discography is a diagnostic test to identify a painful disc. To evaluate the degree of disruption, a combination of discogram and CT scan after discography is used.[1] X-ray findings can also be used to diagnose DDD. Anterior-Posterior and lateral views are taken where presence of osteophytes, narrowing of the disc joint space, or a “vacuum sign” is noted. [10]

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

None of the literature has reported a uniform system of outcome measures. The most common form of outcome measure for DDD is the Oswestry Disabilty Index (ODI) in combination with other forms of outcome measures, such as: Short Form 36 (or SF-12) questionnaire, self-paced walk, timed up-and-go test (TUG),Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and the Roland-Morris disability index (RMDI) [11][12] .

Carreon found that the Oswestry Disability Index is a good primary outcome measure for lumbar fusion and nonsurgical interventions for various symptomatic degenerative spine disorders, [13] although further research is needed.

Examination[edit | edit source]

The patient’s history is a valuable tool for identifying the intervertebral disc as the nociceptive source. Patients may present with a history of chronic LBP as well as symptoms in the gluteal region and stiffness in the spine which worsens with activity and tenderness on palpation over the involved area. [10]

Mood and anxiety disorders are associated with neurological deficits [14] and more commonly seen in patients with lumbar or cervical disc herniation than in those without herniation. No relationship was detected between pain severity and mood or anxiety disorders, however. These disorders can be diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders,

MRI is the most commonly used method of specifically assessing intervertebral disc degeneration. Based on proton density, water content and chemical environment, MRI depicts disc hydration and morphology. Pfirrmann et al devised a grading system for disc degeneration based on MRI signal intensity, disc structure, distinction between nucleus and annulus, and disc height.[15] This useful grading system has been accepted and applied clinically.

The modified system comprises 8 grades for lumbar disc degeneration. [16] Sagittal T2 weighted images were used for classification as they provide a comprehensive perception of disc structure and good tissue differentiation. The 8 grades represent a progression from normal disc to severe disc degeneration with Grade 1 corresponding to no disc degeneration and Grade 8 corresponding to end stage degeneration. As well as the 8 grade table there is also an image reference panel. [16]

Medical management[edit | edit source]

The preferred treatment protocol for patients with chronic low back pain, as a result of disc degeneration, is conservative management of physical therapy and medication. [17]

Conservative treatment includes rest, adequate stimulation for motoractivity, regular physical activity, muscle strengthening, analgesic medication, physiotherapy, rehabilitation programs and lifestyle adjustments, such as weight loss. [18]

Medications such as NSAIDS and acetaminophen (such as Tylenol) help patients to feel confident enough to engage in their regular activities. Stronger prescription medications such as oral steroids, muscle relaxants or narcotic pain medications may also be used to manage intense pain episodes on a short-term basis only and some patients may benefit from an epidural steroid injection. Epidural steroid injections can provide low back pain relief by delivering medication directly to the painful area to decrease inflammation.

Successful outcomes have been demonstrated by animal experiments with mesenchymal stem cells.[18][1] Surgical intervention include disc arthroplasty and lumbar spine [1][18] fusion to reduce the chronic low back pain.[20]

The Device for Intervertebral Assisted Motion (DIAM) is another option of chirurgical management for the treatment of DDD. The DIAM is a polyester encased silicone interspinous dynamic stabilisation device that can unload the anterior column and re-establish the functional integrity of the posterior column. This device is designed for preservation of the functional spinal unit. [21]

In cases where patients are not responsive to nonsurgical treatment, a lumbar total disc replacement (TDR) is an option. Patients presenting with symptomatic single level lumbar DDD who have failed at least 6 months of nonsurgical management were randomly allocated to treatment with an investigational TDR device (also called: TDR activL device) or FDA approved control devices. After 2 years of research, these devices are deemed to be safe and effective for the treatment of symptomatic lumbar DDD. [22]

Physical management[edit | edit source]

One of the main aims of physical therapy is to reduce pain. Various physical modalities are used, including heat and cold application, traction, spinal manipulations [23] (level of evidence 1b) [24] (level of evidence 5) [25] (level of evidence 1a), exercise programs and electrical stimulation such as ‘TENS’ and ‘pulsed radiofrequency (PRF)’ treatment[26] (level of evidence 2a) and lifestyle modifications (e.g., weight reduction, smoking cessation).[27] (level of evidence 1a) Amongst exercise approaches, unloaded movement facilitation exercises of McKenzie, core strengthening, and core stabilisation exercises are all effective in pain reduction for degenerative disc disease.[28] (level of evidence 1a)

Spinal manipulations

Spinal manipulations have traditionally been used to relieve lower back pain, but the effects are generally only temporary. The HVLA (High-Velocity, Low-amplitude) is a manipulation that includes many different techniques and may involve preliminary preparation of the joint and its surrounding tissues, using stretching, assisted motion and other methods. Loads, both forces and moments, are applied to the joint, and it is moved to its end range of voluntary motion. An impulse is then applied, the effective load is the summation of forces applied by the therapist, with the inertial forces generated by the motion of body segments, and the internally generated tensions from client muscle reactions. [29] (level of evidence 3a)

This technique can immediately improve self-perceived pain, spinal mobility in flexion and hip flexion during the passive SLR test, [30] (level of evidence 1b) but Paige et al reported only moderate improvements in pain and with (transient) minor musculoskeletal harms [31] (level of evidence 1a) Before Spinal Manipulation Therapy (SMT) can be considered as a treatment option, patients with LBP need to be screened for possible serious pathology. There are two reasons for this: some conditions, such as a fracture, affect the mechanical integrity of the spine and would make SMT clearly dangerous. In other conditions, a failure to recognise the condition delays commencement of more appropriate care. For example, early detection and treatment of spinal malignancy is important to prevent the spread of metastatic disease and the development of further complications such as spinal cord compression. Application of SMT with the presence of any red flags are considered as contraindications to SMT until further investigation has excluded other pathologies.

Core Stability

Strength training aims to enhance core stability by strengthening and improving the coordination between the abdominal and back muscles.[32] (level of evidence 1b) Stabilisation exercises will increase a patient’s capacity to resist higher loads in the degenerative discs [33]. (level of evidence 1b) This is a key element for prevention and treatment of injury as muscle tissue reduces at a rate of 1 kg/year after the age of 40.[34] (level of evidence 3a) A posterior dynamic stabilisation programme will have result in a significant improvement in pain and disability.[35] (level of evidence 2a) [36] (level of evidence 2a) training exercises performed 1-3 times a week reduces pain and should be continued once pain has subsided and patients are able to return to their jobs and hobbies/activities and are able to cease the use of analgesics.[37] (level of evidence 3a)

Exercises are performed to reduce pain and to ensure stability by strengthening the hip extensors, hip flexors, abdominal muscles and the sacrospinalis muscles.[38] (level of evidence 5) Other important exercises include engaging of the pelvis musculature to restore body symmetry, such as the back extensors and abdominal muscles. The Williams method suggests stretching of the back extensors and strengthening of the abdominal muscles to relieve some of the pressure placed on the lumbar intervertebral discs.[39] [40] (level of evidence 5)

Sample examples of the Williams flexion exercises plan are:

- Pelvic tilt - lying on the back with bent knees, the back is pressed into the floor and held in this position for up to 10 seconds.

- Single or double Knee to chest - Lying on the back with bent knees, one is pulled up to the chest and held for up to 10 seconds. This can be done with one or two knees at a time.

- Partial sit-up - starting in a pelvic tilt position, the shoulders are then lifted off the floor. This is held for 2-10 seconds for each repetition

- Hamstring stretch

- Hip Flexor stretch

- Squat - performed correctlt, this is a good overall exercise for the whole body and trunk control recruitment and lower back strength.

In combination with these exercises core stability exercises are recommended. Exercises to facilitate and engage the transversus abdominis are key to creating a stable base for performing other exercises, including strength exercises. [41] (level of evidence 5)

Exercises can be progressed onto: curl ups, side plank, prone plank, bridging and performing alternated leg and arm raises in a four point kneeling position. This can be progressed to raising opposite arm and leg at the same time. During these exercises the spine should be maintained in a neutral position without any compensatory movements and the pelvis should not tilt. [41] (level of evidence 5) Balance and coordination exercises relevant to an individual's sport can also be added into the programme. [41](level of evidence 5) [42] (level of evidence 5)

In patients with degenerative disc disease it is also advised to add behavioural therapy to treatment programme due to the psychological effects of the disease, as patients can associate the constant pain and term degeneration with their backs becoming increasingly weak, This additional therapy has been shown to give better results. [6] These erroneous thoughts often elicit a fear of movement and can lead to the avoidance of movements of the spine. [33] (level of evidence 1b) Education and advice can also improve patient compliance,[43] (level of evidence 1a) helping them to overcome their fears and be adaptive with their coping strategies. Staying active and physical training will not have adverse effects on their spines[6] and performing low impact aerobic exercises is actually beneficial for the spine, increasing the flow of nutrients and blood to spinal structures and decreases pressure on the intervertebral discs. Prolonged single positions should also be avoided where possible. Back care is a life long process and patients should be encouraged to remain regularly active.[33] (level of evidence 1b) [6]

Extension exercises are given to displace the pressure on the discs anteriorly. Some exercises are:

- Hollowing the back

- Making a sphinx posture

- Gym ball exercises.[44] (level of evidence 5) [45] (level of evidence 5) [46] (level of evidence 2a)

Physical therapies should aim to promote healing in the disc periphery, by stimulating cells, boosting metabolite transport and preventing adhesions and re-injury. Such an approach has the potential to accelerate pain relief in the disc periphery, even if it fails to reverse age-related degenerative changes in the nucleus. [47] (level of evidence 2b)

The use of low-level laser therapy is a further possible option in the conservative treatment of discogenic back pain, with positive clinical results of more than 90% efficacy, not only in the short-term, but also in the long-term, with lasting benefits. In their research, Ip and Fu conducted three sessions of treatment per week over a 12 week period. 49 of the 50 patients had significant improvement in their Oswestry Disability Index score [48],(level of evidence 5) but this needs more research.

Resources

[edit | edit source]

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

DDD is a is a condition in which the intervertebral discs lose height and hydration and as a result the discs are unable to fulfill their primary functions. Although the exact cause of DDD is unknown, it is thought to be primarily associated with the aging process. The most common location of this process is situated in the cervical and lower lumbar regions of the spine.

Diagnosis is via X-ray and to accurately identify the painful disc, a provocation discography test is used. Common outcome measures are the Oswestry Disability Index in combination with questionnaires like VAS and SF-36.

Multiple concepts of medical management are used to treat DDD. Surgical techniques are:

- The DIAM

- Disc arthroplasty

- Lumbar spinei fusion

- Total disc replacement

However, the preferred treatment protocol is conservative management, consisting of physical therapy and analgesic medications. The aim of physical therapy is to reduce pain, to enhance overall strength and core stability and to inform and advise the patient about the disease so that can then effectively self manage for the long term.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Peng B., Pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of discogenic low back pain, World J Orthop 2013 April 18; 4(2): 42-52 LEVEL OF EVIDENCE 1

- ↑ Dr Vanaclocha V., et al, Degeneratieve ziekte van het disc, Clinica Neuros Neurochirurgie, 2010fckLR(http://neuros.net/nl/algemene_degenerative_ziekte_van_disc.php) LEVEL OF EVIDENCE 5

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 McCormack BM, Weinstein PR. Cervical spondylosis. An update. West J Med 1996; 165(1-2): 43-51 (Level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ Chang-jiang Zheng et al.; Disc degeneration implies low back pain; Theoretical Biology and Medical Modelling (2015) (Level of evidence: 2C)

- ↑ Spine-health, Degenerative Disc Disease Health Center, http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/degenerative-disc-disease (asseced 18-05-2016) (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 Dutton M. Orthopaedic Examination, Evaluation, and Intervention. 2nd ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hll; 2008.

- ↑ Ullrich, P. F. (2006 11 6). Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease. Retrieved 06 02, 2009, from Degenerative Disc Disease: http://www.spine-health.com/conditions/degenerative-disc-disease/lumbar-degenerative-disc-disease

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 7SecretsMedical. Degenerative Disc Disease. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UTBrVj7F6kI [last accessed 03/05/13]

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 O'Halloran DM, Pandit AS. Tissue-engineering approach to regenerating the intervertebral disc. Tissue Eng 2007; 13(8):1927-1954.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Thompson, J.C. MD. Netter's Concise Atlas of Orthopaedic Anatomy. (2002) Saunders Elsevier. p.36-7

- ↑ Bono, C. M., & Lee, C. K.; Critical Analysis of Trends in Fusion for Degenerative Disc Disease Over the Past 20 Years: Influence of Technique on Fusion Rate and Clinical Outcome; Spine Volume; 2004; vol. 29; p455-463. (level of evidence: 3A)

- ↑ Malhar N. Kumar, F. J. (2001); Long-term follow-up of functional outcomes and radiographic changes at adjacent levels following lumbar spine fusion for degenerative disc disease; European Spine Journal volume 10; p309-313. (level of evidence: 1B)

- ↑ LY Carreon, S. G.; Fusion and nonsurgical treatment for symptomatic lumbar degenerative disease: a systematic review of Oswestry Disability Index and MOS Short Form-36 outcomes; The spine journal; 2007 (Level of evidence: 3A)

- ↑ Kayhan F, Albayrak Gezer İ, Kayhan A, Kitiş S, Gölen M. Mood and anxiety disorders in patients with chronic low back and neck pain caused by disc herniation. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015 Nov 2:1-5. (level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Pfirrmann CW, Metzdorf A, Zanetti M, et al. Magnetic resonance classification of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration. Spine 2001;26:1873–8 (Level of evidence 2A)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Griffith JF et al; Modified Pfirrmann grading system for lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration; Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2007 Nov 15;32(24):E708-12. ( Level of evidence: 2C)

- ↑ O'Halloran DM, Pandit AS. Tissue-engineering approach to regenerating the intervertebral disc. Tissue Eng 2007; 13(8):1927-1954.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Drazin D., Rosner J., Avalos P., Acosta F., Stem cell therapy for degenerative disc disease, Advances in orthopedics, volume 2012, 8pg LEVEL OF EVIDENCE = 1

- ↑ uwaterloo. Waterloo's Dr. Spine, Stuart McGill. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=033ogPH6NNE [last accessed 03/05/13]

- ↑ Phillips F.M., Slosar P.J., Youssef J.A., Andersson G., Papatheofanis F., Lumbar spine fusion for chronic low back pain due to degenerative disc disease, SPINE Volume 38, Nr 7, Pp. E409-E422, 2013 LEVEL OF EVIDENCE = 1

- ↑ Jean Taylor, M., Patrick Pupin, M., Stephane Delajoux, M., & Sylvain Palmer, M.; Device for Intervertebral Assisted Motion: Technique and Initial Results; Neurosurg Focus; 2007; p1-22. (Level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ Garcia R, Yue JJ, Blumenthal S, Coric D, Patel VV, Leary SP, Dinh DH,fckLRButtermann GR, Deutsch H, Girardi F, Billys J, Miller LE. Lumbar Total DiscfckLRReplacement for Discogenic Low Back Pain: Two-year Outcomes of the activL Multicenter Randomized Controlled IDE Clinical Trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2015 Nov 27 (2B)

- ↑ Beattie P. Current understanding of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration: a review with emphasis upon etiology, pathophysiology, and lumbar magnetic resonance imaging findings. fckLRJOSPT 2008; 38(6):329-340 (level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Zhang Y. Biological treatment for degenerative disc disease: Implications for the field of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2008, fckLR87(9): p.694-702 (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Mirza SK, Deyo RA. Systematic Review of Randomized Trials Comparing Lumbar Fusion Surgery to Nonoperative Care for Treatment of Chronic Back Pain. Spine 2007; 32(7): 816-823 (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Rohof O., Intradiscal pulsed radiofrequency application following provocative discography for the management of degenerative disc disease and concordant pain: a pilot study, Pain practice, 2012, Volume 12, Issue 5, Pg 342-349 (level of evidence 2a)

- ↑ Zhang Y, An HS, Tannoury C, Thonar EJ, Freedman MK, Anderson DG. Biological treatment for degenerative disc disease: implications for the field of physical medicine and rehabilitation. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2008 Sep;87 (level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ lade SC, Keating JL: Unloaded movement facilitation exercise compared to no exercise or alternative therapy on outcomes for people with nonspecific chronic low back pain: a systematic review. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2007;30:301–11(level of evidence: 1A)

- ↑ JJ Triano et al, „Use of chiropractic manipulation in lumbar rehabilitation”, Journal of RehabilitationResearch and Development, 1997. (level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Vieira-Pellenz F et al„Short-Term Effect of Spinal Manipulation on Pain Perception, Spinal Mobility, and Full Height Recovery in Male Subjects With Degenerative Disk Disease: A Randomized Controlled Tria”l, American Congress of Rehabilitation Medicine, 2014 (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24862763) (level of evidence 1B)

- ↑ Paige NM, Miake-Lye IM, Booth MS, Beroes JM, Mardian AS, Dougherty P, Branson R, Tang B, Morton SC, Shekelle PG. Association of Spinal Manipulative Therapy With Clinical Benefit and Harm for Acute Low Back PainSystematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317(14):1451–1460 (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Brox JI, Sorensen R, Friis A. Randomized Clinical Trial of Lumbar Instrumented Fusion and Cognitive Intervention and Exercises in Patients with Chronic Low Back Pain and Disc Degeneration. Spine 2003; 28(17):1913-1921 (level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 12.3 Beattie P. Current understanding of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration: a review with emphasis upon etiology, pathophysiology, and lumbar magnetic resonance imaging findings. fckLRJOSPT 2008; 38(6):329-340 (level of evidence 1b)

- ↑ Adam Gąsiorowski et al, Strength training in the treatment of degeneration of lumbar section of vertebral column, Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, Vol 20, No 2, 203–205, 2013 (level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Zagra A., et al; Prospective study of a new dynamic stabilisation system in the treatment of degenerative discopathy and instability of the lumbar spine, Eur Spine J, 2012, 21, suppl 1: S83-S89 LEVEL OF EVIDENCE 2

- ↑ Canbay S., et al, Posterior dynamic stabilization for the treatment of patients with lumbar degenerative disc disease: long-term clinical and radiological results, Turkish Neurosurgery 2013, vol. 23, No. 2, 188-197 LEVEL OF EVIDENCE 2

- ↑ 41. Adam Gąsiorowski et al, Strength training in the treatment of degeneration of lumbar section of vertebral column, Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, Vol 20, No 2, 203–205, 2013 (level of evidence 3A)

- ↑ Johnson Olubusola E. Therapeutic Exercises in the Management of Non-Specific Low Back Pain, Low Back Pain, ISBN: 978-953-51-0599-2, 2012 (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Lee M.,The effects of core muscle release technique on lumbar spine deformation and low back pain.J Phys Ther Sci.;27(5):1519-22, 2015 (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Mircea MOLDOVAN, Therapeutic Considerations and Recovery in Low Back Pain: Williams vs McKenzie, Timisoara Physical Education and Rehabilitation Journal. Volume 5, Issue 9, 2012 (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 AKUTHOTA V., Core Stability Exercise Principles Akuthota, Curr. Sports Med. Rep., Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 39Y44, 2008 (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ COSIO-LIMA, Effects of Physioball and Conventional Floor Exercises on Early Phase Adaptations in Back and Abdominal Core Stability and Balance in Women. J Strength Cond Res.17(4):721-5. 2003 (level of evidence 5)

- ↑ Mirza SK, Deyo RA. Systematic Review of Randomized Trials Comparing Lumbar Fusion Surgery to Nonoperative Care for Treatment of Chronic Back Pain. Spine 2007; 32(7): 816-823 (level of evidence 1a)

- ↑ Extremiteiten, www.fysio.net, Extensieoefening voor de lumbale wervelkolom in buikligging, 29-10-2009fckLR(http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SNamjanZttM&feature=youtube_gdata) LEVEL OF EVIDENCE 5

- ↑ Kielbaso J., Hardcore abs training, Fit4Less4Info, 19oktober2012fckLR(http://fit4lessamsterdam.wordpress.com/2012/10/) (http://fit4lessamsterdam.files.wordpress.com/2012/10/crunchleg-raise.jpg) LEVEL OF EVIDENCE 5

- ↑ Canbay S., et al, Posterior dynamic stabilization for the treatment of patients with lumbar degenerative disc disease: long-term clinical and radiological results, Turkish Neurosurgery 2013, vol. 23, No. 2, 188-197 (level of evidence 2)

- ↑ Adams MA, Stefanakis M, Dolan P. Healing of a painful intervertebral discfckLRshould not be confused with reversing disc degeneration: implications forfckLRphysical therapies for discogenic back pain. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2010fckLRDec;25(10):961-71. (level of evidence 2B)

- ↑ Ip D, Fu NY. Can intractable discogenic back pain be managed by low-level laser therapy without recourse to operative intervention? J Pain Res. 2015 May 26;8:253-6 (level of evidence 5)