Cortical (Cerebral) Visual Impairment And Its Impact On Children With Cerebral Palsy

When working with a child with Cerebral Palsy (CP), therapists need to look at the whole child and not just their motor skills. Therapists use sensory input to get a desired motor response. Vision plays a major part in a child’s motivation to move and explore their environment. Because there is damage to the brain in a child with CP there is a high probability that there is damage to the visual pathways leading to cortical visual impairment (CVI). Many eye doctors and vision therapists tend to be concerned with the eye structure itself and ignore the cortical impairment. Often eye reports state that there is nothing wrong with the eyes but parents are still concerned that their child is not looking at toys and seeing objects. As therapists we use toys and objects to help a child move and to interact with their surroundings. If the child is having a hard time understanding their environment then they tend to interact less with it. It is important we know how to adapt the surroundings so the child feels safe, secure and wanting to move.

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Cerebral Palsy (CP) is defined as brain damage during utero, delivery and the first two years of development. Many children with CP also have brain damage in the visual processing centers and visual pathways. Cortical visual impairment (CVI) is “a condition in which children have reduced visual acuity as a result of damage to posterior visual pathways.”[1] It is the most common cause of visual impairment in first world countries and is increasing in other countries.

The Brain and Vision[edit | edit source]

Sight as a sense is primarily associated with the eyes but vision is a complex system of the eyes and the brain. The visual stimuli are received by the eye and then are sent to the visual processing centers of the brain via the optic nerve pathway. It is estimated that over 40 percent of the brain is devoted to visual function.[2] The occipital lobes are primarily concerned with vision. The images are sent from the occipital lobes on to the temporal and parietal lobes to be integrated with other sensory input for identification. When there is damage to one or more of these areas then there damage to the visual pathways. However, there is a period of plasticity of the brain to improve visual function with best results between birth and three years of age.

For more information on: Cerebral Visual Impairment: A Brain-Based Visual Condition, watch this video:[edit | edit source]

Medical Conditions[edit | edit source]

The most common conditions associated with CVI are also associated with CP. These are asphyxia, perinatal hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, intraventricular hemorrhage, periventricular leukomalacia, cerebral vascular accident, central nervous system infection, structural abnormalities and trauma.[3]

Click here for a helpful book on: Visual Impairment in Children Due to Damage to the Brain.

Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Cortical visual impairment is diagnosed by:

- A normal eye exam that cannot explain the lack of functional vision;

- A neurological medical diagnosis;

- Presence of unique visual and behavioral characteristics;[4]

- A child can have an ocular issue along with CVI thus making it difficult to determine if the behavior is due to ocular or cortical condition.

The unique visual and behavioral characteristics of CVI are:

- Distinct color preferences – strong color preference, especially red or yellow;

- Attraction to movement – need movement to obtain visual attention and sustain it; either the object or the child can be moving;

- Visual latency – the child is slow in looking at the object;

- Visual field preferences –uncommon field areas and maybe loss of visual fields;

- Difficulties with visual and environmental complexity – difficulty viewing in a complex environment with other sensory input, including noise;

- Light-gazing or non-purposeful gaze;

- Difficulties with distance viewing;

- Absent or atypical visual reflex responses – blink reflex to approaching object is delayed;

- Difficulties with visual novelty – tend to prefer looking at familiar objects;

- Absence of visually guided reach – unable to look and touch an object at same time.

Children with CVI have been described as seeing better some days better than others. This is not true. They see the same but the environment around them is different each day affecting their perception and functional vision.

Follow the link for a book recommendation on Behavioral Characteristics of Children with Permanent Cortical Visual Impairment.

The CVI Range[edit | edit source]

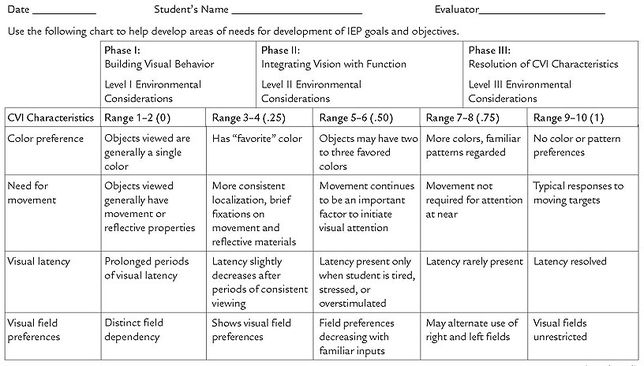

The CVI Range was developed by Christine Roman-Lantzy to assess the functional vision of a child with CVI with a specialized protocol. The assessment encompasses interviews with caregivers and teachers who know the child’s medical history and day to day schedule; observation of the child in their natural environment; and face-to-face evaluation. The Range looks at the child’s behavior in all of the behavioral characteristics and the degree each of the behavioral characteristics interferes with the child’s functional vision. The score is then used to determine if the child is in one of three Phases of CVI:[4]

- Phase I – Building Visual Behavior

- Phase II – Integrating Vision with Function

- Phase III – Resolution of CVI Characteristics

Once the Phase is determined it can be used with the CVI Resolution Chart to determine environmental considerations that should be implemented and needs of visual development.

Phase I – A child tends to view a single color (preference for red or yellow), needs movement to localize the object, is delayed in viewing and tends to have a visual field preference. They attend to an object in a simple environment and do not regard the human face. Sounds and other sensory input hinder their visual attention. They might tend to stare out the window or at the lights or a fan. They might see an object across a room or if it is novel to them. Also they do not look at the object while touching it.

Phase II – A child may now prefer two to three different colors but still need some movement to attend to the object with visual field preferences decreasing. Latency can still be present and increases when the child is tired, stressed, or overstimulated. They start to look at faces and objects further away and no longer stare at the lights. They start to reach for familiar objects while looking at it.

Phase III – A child no longer has a strong color, object or visual field preference, latency and look and touch are resolved. Auditory stimuli can be tolerated in a musical toy or in the room. Visual novelty and complex environments are still concerns.

Watch this video on Cortical Visual Impairment and the Evaluation of Functional Vision:[edit | edit source]

Therapy Implications[edit | edit source]

Phase I – When working with a child with CP in Phase I they need to be in a simple environment with subdued lighting and decreased noise – this includes no to minimal talking while having them look for the object. Present the child a toy that is one color and has some movement. Introduce the toy in a variety of visual fields and give the child time to respond. Remember that your clothing presents a complex visual field so wearing a black shirt and having them on a plain blanket or mat while working with a child in Phase I will decrease the complexity. The therapist might use a red light up ball to get a child to track and roll to their side then to their tummy.

Phase II – Use the same color object in a variety of familiar places or start to use a couple of colors during therapy. The child still might need movement and the object be shiny. They might still have a visual field preference and be slower in responding. They might be able to tolerate people talking around them when they are not stressed or tired. Visual complexity is still difficult so limit toys with noise, lots of color, and many toys around the child. Have a child crawl towards a red ball and put it into a yellow container.

Phase III – A child in Phase III will now play with objects of different colors but might have difficulty with objects with a lot of detail. Their preferred color can be used to help them focus their attention in a complex environment. For example, placing red tape around their bedroom door when trying to get them to navigate their wheelchair through the doorway. They might still need movement or shininess for distance. Continue to give them time to respond or find the visual field they need. They can tolerate more noise around them and need someone to describe then consistent features of objects.

Click here to learn more about building strategies around the CVI phases.

For more information on CVI interventions, please click here.

For more information, take a look at this classic literature on cortical visual impairment:

- Jan, J. E., Groenveld, M., & Anderson, D. O. (1993). Photophobia and cortical visual impairment. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 35(6), 473-477.

- Jan, J., Groenveld, M., Sykanda, A. M., & Hoyt, C. (1987). Behavioral characteristics of children with permanent cortical visual impairment. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 29(5), 571-576.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Skoczenski,A.M , & Good, W.V. (2004). Vernier acuity is selectively affected in infants and children with cortical visual impairment. Dev Med Child Neurol. 46(8):526-32.

- ↑ Dutton, G. N., McKillop, E. C., & Saidkasimova S. (2006). Visual problems as a result of brain damage in children. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 90(8), 932-933.

- ↑ Huo, R., Burden, S. K., Hoyt, C. S., & Good, W. V. (1999). Chronic cortical visual impairment in children: Aetiology, prognosis, and associated neurological deficits. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 83, 670-755.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Roman-Lantzy, C. Cortical Visual Impairment: An Approach to Assessment and Intervention (New York, AFB Press, 2007).