Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19)

Please note: this is a rapidly developing topic and while we will try to keep this page up to date please let us know if you are aware of any new information or evidence that should be incorporated into this page. (28/05/2020)

Original Editor - Rachael Lowe

Top Contributors - Rachael Lowe, Wanda van Niekerk, Kim Jackson, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Nikhil Benhur Abburi, Candace Goh, Tolulope Adeniji, Vidya Acharya, Jess Bell, Tarina van der Stockt, Anas Mohamed, Nicole Hills, Marleen Moll, Tony Lowe, Richard Benes, Oyemi Sillo, Natalie Patterson, Olajumoke Ogunleye, Simisola Ajeyalemi and Leana Louw

Introduction to COVID-19[edit | edit source]

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has declared the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) a pandemic[1]. A global coordinated effort is needed to stop the further spread of the virus. A pandemic is defined as “occurring over a wide geographic area and affecting an exceptionally high proportion of the population.”[2] The last pandemic reported in the world was the H1N1 flu pandemic in 2009.

On 31 December 2019, a cluster of cases of pneumonia of unknown cause, in the city of Wuhan, Hubei province in China, was reported to the World Health Organisation. In January 2020, a previously unknown new virus was identified[3][4], subsequently named the 2019 novel coronavirus, and samples obtained from cases and analysis of the virus’ genetics indicated that this was the cause of the outbreak. This novel coronavirus was named Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) by WHO in February 2020.[5] The virus is referred to as SARS-CoV-2 and the associated disease is COVID-19[6].

As of 15 May 2020, over 4,444,670 cases have been identified globally in 188 countries with a total of over 302,493 fatalities. Also 1,588,858 were recovered Live data can be accessed here.

[edit | edit source]

Coronaviruses are a family of viruses that cause illness such as respiratory diseases or gastrointestinal diseases. Respiratory diseases can range from the common cold to more severe diseases eg

- Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS-CoV)

- Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS-CoV)[10].

A novel coronavirus (nCoV) is a new strain that has not been identified in humans previously. Once scientists determine exactly what coronavirus it is, they give it a name (as in the case of COVID-19, the virus causing it is SARS-CoV-2).

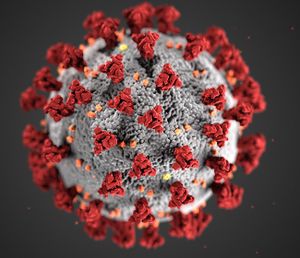

Coronaviruses got their name from the way that they look under a microscope. The virus consists of a core of genetic material surrounded by an envelope with protein spikes. This gives it the appearance of a crown. The word Corona means “crown” in Latin.

Coronaviruses are zoonotic[11], meaning that the viruses are transmitted between animals and humans. It has been determined that MERS-CoV was transmitted from dromedary camels to humans and SARS-CoV from civet cats to humans[10]. The source of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) is yet to be determined, but investigations are ongoing to identify the zoonotic source to the outbreak[12].

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Typically Coronaviruses present with respiratory symptoms. Among those who will become infected, some will show no symptoms. Those who do develop symptoms may have a mild to moderate, but self-limiting disease with symptoms similar to the seasonal flu[13]. Symptoms may include:

- Respiratory symptoms

- Fever

- Cough

- Shortness of breath

- Breathing difficulties

- Fatigue

- Sore throat

A minority group of people will present with more severe symptoms and will need to be hospitalised, most often with pneumonia, and in some instances, the illness can include ARDS, sepsis and septic shock[13][14]. Emergency warning signs where immediate medical attention should be sought[15] include:

- Difficulty breathing or shortness of breath

- Persistent pain or pressure in the chest

- New confusion or inability to arouse

- Bluish lips or face

High-Risk Populations[edit | edit source]

The virus that causes COVID-19 infects people of all ages. However, evidence to date suggests that two groups of people are at a higher risk of getting severe COVID-19 disease[16]:

- Older people (people over 70 years of age)

- People with serious chronic illnesses such as:

- Diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease

- Chronic respiratory disease

- Cancer

- Hypertension

- Chronic liver disease

The WHO has issued and published advice for these high-risk groups and community support. This is to ensure that these high-risk populations are protected from COVID-19 without being isolated, stigmatised, left in positions of increased vulnerability or unable to have access to basic provisions and social care.

WHO advice for high-risk populations[16]:

- When having visitors at your home, extend “1-meter greetings”, like a wave, nod or bow.

- Request that visitors and those who live with you, wash their hands.

- Clean and disinfect surfaces in your home (especially those that people touch a lot) on a regular basis.

- Limit shared spaces if someone you live with is not feeling well (especially with possible COVID-19 symptoms).

- If you show signs and symptoms of COVID-19 illness, contact your healthcare provider by telephone, before visiting your healthcare facility.

- Have an action plan in preparation for an outbreak of COVID-19 in your community.

- When you are in public, practice the same preventative guidelines as you would at home.

- Keep updated on COVID-19 through obtaining information from reliable sources.

Transmission of COVID-19[edit | edit source]

Evidence is still emerging, but current information is indicating that human-to-human transmission is occurring. The routes of transmission of COVID-19 remains unclear at present, but evidence from other coronaviruses and respiratory diseases indicates that the disease may spread through large respiratory droplets and direct or indirect contact with infected secretions[17].

The incubation period of COVID-19 is currently understood to be between 2 to 14 days[15]. This means that if a person remains well after 14 days after being in contact with a person with confirmed COVID-19, they are not infected.

Preventing Transmission[edit | edit source]

The WHO suggests the following basic preventative measures to protect against the new coronavirus[19][20]

- Stay up to date with the latest information on the COVID-19 outbreak through WHO updates or your local and national public health authority.

- Perform hand hygiene frequently with an alcohol-based hand rub if your hands are not visibly dirty or with soap and water if hands are dirty.

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose and mouth.

- Practice respiratory hygiene by coughing or sneezing into a bent elbow or tissue and then immediately disposing of the tissue.

- Wear a medical mask if you have respiratory symptoms and performing hand hygiene after disposing of the mask.

- Maintain social distancing (approximately 2 meters) from individuals with respiratory symptoms.

- If you have a fever, cough and difficulty breathing seek medical care.

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

A COVID-19 diagnostic testing kit has been developed and is available in clinical testing labs[22]. The gold standard for testing for COVID-19 is Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR). However, current data suggest that RT-PCR is only 30-70% effective for acute infection, this may be due to incorrect use of lab kits or not enough virus in the blood at the early stages of testing. Plus, the availability of testing will vary from country to country.

The CDC recommends that any person who may have had contact with a person who is suspected of having COVID-19 and develops a fever and respiratory symptoms listed above are advised to call their healthcare practitioner to determine the best of course of action[23]. The main criteria for testing are:[24]

- Location

- Age

- Medical history and risk factors

- Exposure to the virus and contact history

- Duration of symptoms

If the above criteria are met it is advised that the following testing procedure is followed:[22]

- Collect and test upper respiratory tract specimens, using a nasopharyngeal swab

- If available testing of lower respiratory tract specimens

- If a productive cough is evident then a sputum specimen should be collected

- For patients who are receiving invasive mechanical ventilation, a lower respiratory tract aspirate or broncho-alveolar lavage sample should be collected

Imaging may be useful in identifying patients with COVID-19 which is especially relevant in places with good access to imaging technology but poor access to reliable and quick laboratory testing[25]. Chest X-rays are not especially sensitive for COVID-19, but chest CT gives a much more detailed view appears to have good sensitivity in initial stages of the disease[26]. However chest CT or X-ray is not currently recommend as a diagnostic method as they can easily be confused with other infections such as H1N1, SARS, MERS and seasonal flu. Lung ultrasound is also emerging as a valuable diagnostic testing procedure. According to the CDC, even if a chest CT or X-ray suggests COVID-19, viral testing is the only specific method for diagnosis[27].

Case Definitions[edit | edit source]

The definitions used by the WHO in COVID-19:[28]

Suspect case:

Patient with acute respiratory illness (fever and at least one other symptom such as cough or difficulty breathing (shortness of breath)) AND with no other aetiology that explains symptoms AND a history of travel to a country/area that reported transmission of SARS-CoV-2 virus

OR

Patient with acute respiratory illness AND who have been in contact with a confirmed or probable COVID-19 case in the last 14 days prior to the onset of signs and symptoms

OR

Patient with severe respiratory illness (fever and at least one other symptom such as cough or difficulty breathing (shortness of breath)) AND that requires hospitalisation AND with no other aetiology that explains clinical picture/presentation of the patient

Probable case:

A probable case is a suspected case for whom the report from laboratory testing for the COVID-19 virus is inconclusive.

Confirmed case:

A confirmed case is a person with laboratory confirmation of infection with the COVID-19 virus, irrespective of clinical signs and symptoms.

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Differential diagnosis should include the possibility of a wide range of common respiratory disorders such as:

- Other Coronaviruses (SARS, MERS)

- Adenovirus

- Influenza

- Human metapneumovirus (HmPV)

- Parainfluenza

- Respiratory syncytial virus (RSV)

- Rhinovirus (common cold)

- Bacterial pneumonia, mycoplasma pneumonia (MPP) and chlamydia pneumonia[29].

Differentiation should also be made from lung disease caused by other diseases[30]. A CT scan has great value in early screening and differential diagnosis for COVID-19 [31].

Management / Interventions[edit | edit source]

In the case of mild to moderate symptoms the following considerations should be taken into account:

- Early identification - Clinicians, especially physiotherapists, are most often in direct contact with their patients, which can make them infected or infected by others. It is therefore very important for physiotherapists and other health professionals to be familiar with the condition of COVID-19, how to identify it and how to prevent it.

- Strategies for infection prevention and control (IPC) - Suspect, probable and confirmed cases should be educated on IPC strategies to prevent transmission of the disease and health management strategies for quarantine.

Find out more about the role of the physiotherapist in COVID-19 here.

For hospitalised patients the WHO highlights several considerations[14]:

- Recognising and sorting patients with severe acute respiratory disease - Early recognition of suspected patients allows for timely initiation of IPC. Early identification of those with severe manifestations allows for immediate, optimised supportive care treatments and safe, rapid admission (or referral) to the intensive care unit according to institutional or national protocols. For those with mild illness, hospitalisation may not be required unless there is a concern for rapid deterioration. All patients discharged home should be instructed to return to the hospital if they develop any worsening of illness.

- Strategies for infection prevention and control (IPC) - IPC is a critical and integral part of the clinical management of patients and should be initiated at the point of entry of the patient to the hospital. Standard precautions should always be routinely applied in all areas of health care facilities. Standard precautions include hand hygiene; use of PPE to avoid direct contact with patients’ blood, body fluids, secretions (including respiratory secretions) and non-intact skin. Standard precautions also include prevention of needle-stick or sharps injury; safe waste management; cleaning and disinfection of equipment; and cleaning of the environment.

- Early supportive therapy and monitoring - Give supplemental oxygen therapy immediately to patients with severe acute respiratory illness (SARI) and respiratory distress, hypoxaemia, or shock. Use conservative fluid management in patients with SARI when there is no evidence of shock. Closely monitor patients with SARI for signs of clinical deterioration, such as rapidly progressive respiratory failure and sepsis, and apply supportive care interventions immediately. Understand the patient’s co-morbid condition(s) to tailor the management of critical illness and appreciate the prognosis. Communicate early with the patient and family.

- Collection of specimens for laboratory diagnosis - Collect blood cultures for bacteria that cause pneumonia and sepsis, ideally before antimicrobial therapy. Collect specimens from both the upper respiratory tract (nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal) and lower respiratory tract.

- Management of respiratory failure and ARDS - Recognise severe hypoxaemic respiratory failure when a patient with respiratory distress is failing standard oxygen therapy. In the case of respiratory failure, intubation and protective mechanical ventilation may be necessary[32]. Non-invasive techniques can be used in non-severe forms, however, if the scenario does not improve or even worsen within a short period of time (1–2 hours) then mechanical ventilation must be preferred[32].

- Management of septic shock - Haemodynamic support is essential for managing septic shock[32].

- Prevention of complications - Implement the following interventions to prevent complications associated with a critical illness such as:

- reduce days of invasive mechanical intervention

- reduce the risk of ventilator-associated pneumonia

- reduce the risk of venous thromboembolism

- reduce the risk of pressure ulcers

- reduce the incidence of ICU related weakness

- Treatment interventions - There is no current evidence from RCTs to recommend any specific anti-nCoV treatment for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-2019 infection.

For more details on the management of hospitalised patients see this WHO document.

Find out more about the physiotherapy management of people with COVID-19 here:

Use of Personal Protective Equipment[edit | edit source]

The type of personal protective equipment (PPE) used when caring for COVID-19 patients will vary according to the setting and type of personnel and activity. Healthcare workers involved in the direct care of patients should use the following PPE: gowns, gloves, medical mask and eye protection (goggles or face shield). Specifically, for aerosol-generating procedures (e.g., tracheal intubation, non-invasive ventilation, tracheostomy, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, manual ventilation before intubation, bronchoscopy) healthcare workers should use respirators, eye protection, gloves and gowns; aprons should also be used if gowns are not fluid resistant[33]. Among the general public, persons with respiratory symptoms or those caring for COVID-19 patients at home should receive medical masks.

For asymptomatic individuals, wearing a mask of any type is not recommended. Wearing medical masks when they are not indicated may cause unnecessary cost and a procurement burden and create a false sense of security that can lead to the neglect of other essential preventive measures[34].

WHO has provided a document that specifically outlines the recommended type of personal protective equipment (PPE) to be used in the context of COVID-19 disease, according to the setting, personnel and type of activity, you can see it here.

In the case of a pandemic, supplies of PPE may become limited. Strategies to optimise the availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) include[20]:

- Minimise the need for PPE by considering telemedicine (providing health care remotely), using physical barriers such as glass or plastic windows e.g. in receptions, restricting healthcare workers not involved in care from being in close proximity with COVID-19 patients.

- Ensure PPE use is rationalised and appropriate by assessing the risk of exposure and transmission.

- Coordinate PPE supply chain mechanisms.

Special Population Considerations[edit | edit source]

Older People[edit | edit source]

Although the virus can infect people of all ages, evidence suggests that older people (those of 60 years old) have an increased risk of developing a severe form of the disease.[16] This may be due to:

- Ageing is associated with a decline in immune function

- Higher risk of co-morbidities (Diabetes, Heart Disease, Lung Conditions, Cancer)

- Residence/Location - Many older people live in care homes or nursing facilities, where the disease can spread more rapidly

To read more about Infection Control in Older Adults see here

Disabled[edit | edit source]

People with disability may be at greater risk of contracting COVID-19 because of[35]:

- Barriers to implementing hand hygiene.

- Difficulty in enacting social distancing.

- The need to touch things to obtain information from the environment or for physical support.

- Barriers to accessing public health information.

- Barriers to accessing healthcare.

This WHO document, Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak, outlines actions for authorities, healthcare workers, disability service providers, the community, people with disability and their household.

Pregnant Women and Newborns[edit | edit source]

The risk for adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes associated with COVID-19 is largely unknown, but medical experts suspect symptoms of COVID-19 may be more severe in pregnant woman compared to non-pregnant women[36]. This may be due to changes in their bodies and immune systems pregnant women can be badly affected by some respiratory infections[37]. Women with COVID-19 can breastfeed and have close contact with their newborn, but they should diligently perform respiratory and hand hygiene[37]. No evidence so far that babies have active coronavirus transmitted from mothers

Low and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs)[edit | edit source]

The link between mortality and health care resources in the COVID-19 pandemic may cause concerns for LMICs because[38]:

- Inability to afford large-scale diagnostics.

- ICU beds and personnel trained in critical care may be limited.

- Inability to fund the additional cost of critical care units from limited health budgets.

- Disruption of supply chains and depletion of stock, such as medical supplies, equipment and PPE.

- High numbers of internally displaced people and displace refugees who often have co-morbidities and reside in large-scale camps[39].

Resources[edit | edit source]

Physiotherapy Member Organisation by Country: Best Practices for Coronavirus

- https://www.wcpt.org/news/Novel-Coronavirus-2019-nCoV - WCPT list of links to various global organisations and resources

Governmental Information for Health Professionals

- https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/wuhan-novel-coronavirus - UK

- https://www.health.qld.gov.au/news-events/news/novel-coronavirus-covid-19-sars-queensland-australia-how-to-understand-protect-prevent-spread-symptoms-treatment - Australia

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-nCoV/hcp/index.html - CDC (US)

- https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019 - WHO

- https://openwho.org/ - Free Online Coursework via WHO

- https://www.un.org/coronavirus - United Nations

- https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/COVID-19-infection-prevention-and-control-healthcare-settings-march-2020.pdf - European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

Overview Resources and Factsheets

- https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/communication/factsheets.html

- https://www.cochrane.org/news/special-collection-coronavirus-covid-19-evidence-relevant-critical-care - Evidence Relevant to Critical Care (Cochrane)

- https://www.cdc.gov/flu/professionals/infectioncontrol/resphygiene.htm - Infection Control Respiratory Hygiene

- https://www.thelancet.com/coronavirus?dgcid=etoc-edschoice_email_tlcoronavirus20 - The Lancet COVID-19 Resource Center

- https://www.coursera.org/learn/covid-19?#syllabus - This is a current online course offered through Imperial College London

- https://coronavirus.jhu.edu - the Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center

- JAMA network Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) - research articles related to the pandemic

- Respiratory physiotherapy in patients with COVID-19 infection in acute setting: a Position Paper of the Italian Association of Respiratory Physiotherapists (ARIR)

- Link to a real-time map of global cases by Johns Hopkins University This article explains it further

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ World Health Organization. WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 (Accessed 14 March 2020)

- ↑ Marriam Webster Dictionary. Pandemic. Available from:https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/pandemic (Accessed 14 March 2020)

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Novel Coronavirus – China.Disease outbreak news : Update 12 January 2020.

- ↑ Wikipedia. Timeline of the 2019–20 coronavirus pandemic in November 2019 – January 2020. Available from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Timeline_of_the_2019%E2%80%9320_coronavirus_pandemic_in_November_2019_%E2%80%93_January_2020. [last accessed 17 March 2020]

- ↑ World Health Organization. Director-General's remarks at the media briefing on 2019-nCoV on 11 February 2020. 2020/2/18)[2020-02-21]. https://www. who. int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-generals-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-2019-ncov-on-11-february-2020. 2020.

- ↑ Public Health England. COVID-19: epidemiology, virology and clinical features. Available from:https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-background-information/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-epidemiology-virology-and-clinical-features (Accessed 14 March 2020)

- ↑ . World Health Organisation.Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV). Published on 31 January 2020. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mOV1aBVYKGA&t=88s [last accessed 16 March 2020]

- ↑ World Health Organisation. WHO: Coronavirus - questions and answers (Q&A). Published on 16 January 2020. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OZcRD9fV7jo&t=8s [last accessed 16 March 2020]

- ↑ Osmosis. COVID-19 (Coronavirus disease 2019) March update-causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatment, pathology. Published on 15 March 2020. Available from:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JKpVMivbTfg [last accessed 16 March 2020]

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 World Health Organization. Coronavirus. Available from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/coronavirus (Accessed 14 March 2020)

- ↑ Chan JF, Lau SK, To KK, Cheng VC, Woo PC, Yuen KY. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: another zoonotic betacoronavirus causing SARS-like disease. Clinical microbiology reviews. 2015 Apr 1;28(2):465-522.

- ↑ Public Health England. COVID-19: epidemiology, virology and clinical features. Available from:https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-background-information/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-epidemiology-virology-and-clinical-features. (Accessed 14 March 2020)

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Moses R. COVID-19:Respiratory Physiotherapy On Call Information and Guidance. Lancashire Teaching Hospitals. March 2020.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 World Health Organisation. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected. January 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/clinical-management-of-novel-cov.pdf Accesed 15 March 2020

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Symptoms. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/symptoms.html Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 World Health Organisation. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report - 51. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200311-sitrep-51-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=1ba62e57_10 Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ Public Health England. COVID-19: epidemiology, virology and clinical features. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-background-information/wuhan-novel-coronavirus-epidemiology-virology-and-clinical-features. Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ World Health Organisation. How to protect yourself against COVID-19. Published on 28 February 2020. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1APwq1df6Mw&t=6s. [last accessed 16 March 2020]

- ↑ World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) advice for the public. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/advice-for-public Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 World Health Organisation. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331215/WHO-2019-nCov-IPCPPE_use-2020.1-eng.pdf Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ World Health Organisation.What can people do to protect themselves and others from getting the new coronavirus? Published on 5 February 2020. Available from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bPITHEiFWLc [last accessed 16 March 2020]

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Evaluating and Testing Persons for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-criteria.html?CDC_AA_refVal=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.cdc.gov%2Fcoronavirus%2F2019-ncov%2Fclinical-criteria.html Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Testing for COVID-19 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/symptoms-testing/testing.html Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ Centers for Disease Prevention and Control. Information for Health Departments on Reporting a Person Under Investigation (PUI), or Presumptive Positive and Laboratory-Confirmed Cases of COVID-19 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/php/reporting-pui.html Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ Osmosis. Diagnosing COVID-19 with Chest CT Findings. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7de8LJE4owg Accessed 16 March 2020.

- ↑ Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19): Clinical Care. March 2020 https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/clinical-guidance-management-patients.html Accessed 16 March 2020

- ↑ ACR Recommendations for the use of Chest Radiography and Computed Tomography (CT) for Suspected COVID-19 Infection. March 2020. https://www.acr.org/Advocacy-and-Economics/ACR-Position-Statements/Recommendations-for-Chest-Radiography-and-CT-for-Suspected-COVID19-Infection. Accessed 16 March 2020.

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Global Surveillance for human infection with coronavirus disease (COVID-19). https://www.who.int/publications-detail/global-surveillance-for-human-infection-with-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov) Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ Ishiguro, T, Kobayashi, Y, Uozumi, R, et al. Viral pneumonia requiring differentiation from acute and progressive diffuse interstitial lung diseases. Intern Med. 2019;58(24):3509–3519.

- ↑ Yoo, JH . The fight against the 2019-nCoV outbreak: an arduous march has just begun. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(4):e56.

- ↑ Dai, W. C., Zhang, H. W., Yu, J., Xu, H. J., Chen, H., Luo, S. P., ... & Lin, F. (2020). CT imaging and differential diagnosis of COVID-19. Canadian Association of Radiologists Journal, 0846537120913033.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Marco Cascella; Michael Rajnik; Arturo Cuomo; Scott C. Dulebohn; Raffaela Di Napoli. Features, Evaluation and Treatment Coronavirus (COVID-19). March 2020 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554776/Accessed online 15 march 2020

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Advice on the use of masks in the community, during home care and in health care settings in the context of the novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) outbreak. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/advice-on-the-use-of-masks-in-the-community-during-home-care-and-in-healthcare-settings-in-the-context-of-the-novel-coronavirus-(2019-ncov)-outbreak Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331215/WHO-2019-nCov-IPCPPE_use-2020.1-eng.pdf Accessed 14 March 2020

- ↑ World Health Organisation. Disability considerations during the COVID-19 outbreak [Internet]. March 2020. [Accessed: 3 April 2020]

- ↑ Weigel G. Womens Health Policy: Novel Coronavirus “COVID-19”: Special Considerations for Pregnant Women. March 2020.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 World Health Organisation. Q&A on COVID-19, pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. March 2020 Accessed 23 March 2020

- ↑ Hopman J, Allegranzi B, Mehtar S. Managing COVID-19 in Low-and Middle-Income Countries. JAMA. 2020 Mar 16.

- ↑ Inter Agency Standing Committee. Scaling-Up COVID-19 Outbreak Readiness Response Operations in Humanitarian Situations. March 2020.