Core Stability

Original Editor - Sem Bras

Top Contributors - Sheik Abdul Khadir, Katherine Knight, Lucinda hampton, Khloud Shreif, George Prudden, Sem Bras, Vanessa Rhule, WikiSysop, Yagdutt Yagdutt, Admin, Kim Jackson, Wanda van Niekerk and Venus Pagare

Definition[edit | edit source]

For proper movement and to perform a wide spectrum of functions and activities "stability" is required, it is provided in a co-ordinated manner by the active structures (eg muscles), passive structures (eg lumbar spine), and control by neurological systems[1].

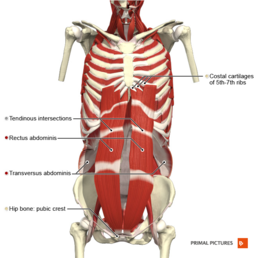

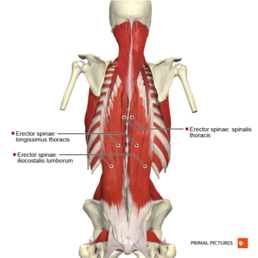

Core stability (CS) was introduced for the first time in 1990s by (Hodges and Richardson) during studying the timing of trunk muscles in patients with chronic low back pain CLBP[2]. There is controversy and some confusion on the definition of the term “core stability”[3][4][5]. Traditionally this term has referred to the active component to the stabilizing system including deep/local muscles that provide segmental stability (eg transversus abdominis, lumbar multifidus) and/or the superficial/global muscles (eg rectus abdominis, erector spinae) that enable trunk movement/torque generation and also assist in stability in more physically demanding tasks.[3]

CS is defined as the ability to maintain equilibrium and control of your spine and pelvic region during movement without compensatory movement just within physiological limits.

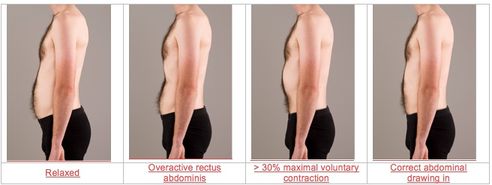

Different proponents have advocated different types of core stability exercises ranging from the abdominal drawing in maneuver (Figure 1) to sit ups or “plank” type exercises (Figure 2).

Training the local muscles (developed by physiotherapists) is a complex skill for the participant and the trainer that requires precise and rigorous assessment, exercise instruction, and feedback. Training the superficial muscles can be equally complex and is undertaken by a range of health and sporting professionals with a large variety approaches evident. An alternative term to “core stability” is “motor control” that reflects concepts around lumbar stability in a more holistic approach including: the brain, sensory inputs, motor outputs, mechanical properties of muscles/joints, what is normal/abnormal and what may be adaptive/maladaptive.[4]

Clinically relevant anatomy[edit | edit source]

Local/ deep muscles: muscles that contribute to joint stability and located more centrally near the joint anatomically attaches to many parts of passive elements of the joint to provide stability for the joint during movement.

The local/deep muscles have their origin or insertion on the lumbar vertebra therefore can exert a segmental stabilizing/stiffening effect[6][7]. Local muscles are;

The mechanism of the deep muscles stability is controversial but transversus abdominis may act like a canister with the diaphragm and pelvic floor muscles. This co-contraction increases the intra-abdominal pressure, which creates an extension moment at the spine and has been hypothesized that increasing stability/stiffness in particular via connections with the thoracolumbar fascia.[6] The multifidus may increase the rotational segmental stability in the sagittal and horizontal plan.[6]

Normal function of the deep muscle system is impaired with back pain.[4] There is strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of treatment aimed at normalizing this function by way of specific motor control training, and specific muscle activation[8].

Global muscles

There are a wide range of superficial/global muscles that are large, cross multiple segments, responsible for movement. attach the pelvis trunk to the thoracic or upper limb and lower limb and do not attach directly to the vertebrae for example;

Parts of the erector spinae.

These muscles generate torque, acting like guy ropes to control spinal orientation and work in co-contraction to control spinal motion in the application of external loads.

Identifying muscle dysfunction [9][edit | edit source]

Local / deep muscles

Assessment of the function of the local/deep muscles is analogous with providing treatment. An understanding of the normal response is required for the abdominal drawing-in maneuver (transversus abdominis), isometric activation of multifidus, normal breathing (diaphragm), and pelvic floor activation.

Global/superficial muscles

There is a wide range of tests for the dysfunction of the global muscles regarding core stability/motor control. There are definitive texts on this topic [2] as well as specific tests listed below:

- Prone instability test

- Prone extension endurance test (Biering-Sorenson paraspinal endurance strength)

- Side bridge endurance test (quadratus lumborum endurance strength)

- Pelvic bridging

- Leg lowering test (lower abdominal strength)

- Trunk curl

- Hip external rotation strength

- Modified Trendelenburg test (single leg squat with observation in the frontal plane)

- Single leg squat in the sagittal plane

- Single leg squat in the transverse plane

These tests for local and global muscle function should be applied and interpreted using clinical reasoning principles within a broad understanding of normal/abnormal motor control. There is preliminary evidence for a clinical prediction rule identifying people with low back problems more likely to respond to specific motor control/specific muscle activation of the local muscles [7]:

- Younger age (<40)

- Greater general flexibility (hamstring length greater than 90°, postpartum)

- Positive prone instability test

- Presence of aberrant movement during spinal range of motion (painful arc of motion, abnormal lumbopelvic rhythm, and using arms on thighs for support)

Management principles[edit | edit source]

Here are some examples of exercises to improve the motor control /core stability of the lumbar spine.

Local/deep muscles

People with significant pathology where there is local muscle dysfunction, are likely to retrain a specific motor control before moving into more global training.[11]

Global /superficial muscles

It is important for practitioners/sports personnel attempting to global/superficial muscle strength to have a clear understanding of any pathoanatomical problems that may be positively or negatively affected by such exercise. Ideally, all of these exercises should be done with correct lumbopelvic posture and control of the local/deep muscles. With most of these exercises duration of hold and repetitions can be varied (depending on the aim of the retraining/strengthing program) provided the exercise is done with good control.

Crunches- Lie supine on the floor with your knees bent, arms crossed over your chest and the feet flat on the floor. Then lift your shoulders from the ground and curl your stomach. Avoid a full sit up and ensure the low back remains in contact with the floor.

Obliques crunches - As per a normal crunch but leading with one shoulder towards the opposite knee (alternate sides each repetition).

Plank - Lie prone on the floor. Then while keeping your whole trunk straight (like a plank) lift up onto your forearms, with the elbows right under the shoulders, and toes. Hold this position as long as possible with control. To make the exercise more difficult try to lift one leg slightly of the ground. Balls/balance devices can also be used under the arms or feet. The plank can also be done on your side while supported by your feet and your forearm with your shoulder above your elbow.

Bridges - Lie supine with your knees bent and the feet flat on the floor. Lift your pelvis off the ground while supporting on your feet and shoulders. The bridge can be progressed by lifting one foot off the ground end extending the knee.

Hamstring raises - Balance on your hands and knees with your back flat and your arms/thighs perpendicular to the floor. Raise one leg behind you until it is horizontal. Alternate.

Superman – As per a hamstring raise but progress by lifting the opposite arm to a horizontal position at the same time. Alternate.

Leg raises - Lie on your back with your legs straight and your arms by your sides. Then lift one leg 4 inches of the ground. Your back has to stay flat on the floor. Don’t allow it to arch. Alternate. The exercise can be progressed by lifting both legs at the same time.

Hundreds - Lie on your back with your legs straight and your arms by your sides. Then lift both legs so that they form a right angle in the hip and knees. Lift your arm straight a few inches off the ground. Focus on keeping your hips and legs completely still and your back flat.

There are also multiple exercises that can be performed with a physioball. The exercises were proven to have a greater gain of torso balance and neural activity than regular floor exercises.[18]

Akuthota et al gave an example of how to build up a program with these exercises [9]

- Go over the anatomy of the core

- Active participation emphasized

- Local/deep muscle activation – progress once able to perform 30 reps with 8 second hold.

- Abdominal bracing

- Bracing with heel slides

- Bracing with leg lifts

- Bracing with bridging

- Bracing in standing

- Bracing with standing row

- Bracing with walking Paraspinals/multifidis (advance if able to perform 30 reps with 8 s hold)

- Quadruped arm lifts with bracing

- Quadruped leg lifts with bracing

- Quadruped alternate arm and legs lifts with bracing

- Quadratus lumborum and obliques (advance if able to perform 30 reps with 8 s hold)

- Side plank with knees flexed

- Side plank with knees extended

- Trunk curl Facilitation techniques if necessary (pelvic floor contraction, visualization, palpation, identifying substitution patterns like pelvic tilt, ultrasound)

- Functional training positions with activation of the core

Summary[edit | edit source]

There is no single muscle or single exercise for low back problems and motor control/core stability as a treatment. At a minimum practitioners/sports personnel should be aware of key concepts in motor control and exercise and follow an evidence-based approach to exercise prescription.

Currently, there is strong evidence for specific motor control/specific muscle activation in isolation, progressing to more global and functional exercises.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Willson JD, Dougherty CP, Ireland ML, Davis IM. Core stability and its relationship to lower extremity function and injury. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2005 Sep 1;13(5):316-25.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lederman E. The myth of core stability. Journal of bodywork and movement therapies. 2010 Jan 1;14(1):84-98.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jin ZH, Kibler WB, Press J, Sciascia A. The role of core stability in athletic function. Journal of Beijing Sport University. 2008;12:039.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4. Panjabi MM. The stabilizing system of the spine. Part II. Neutral zone and stability hypothesis. J Spinal Disord. 1992;5:383-9.

- ↑ Akuthota V, Ferreiro A, Moore T, Fredericson M. Core stability exercise principles. Current sports medicine reports. 2008 Jan 1;7(1):39-44.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Delitto A, Erhard RE, Bowling RW. A treatment-based classification approach to low back syndrome: identifying and staging patients for conservative treatment. Physical therapy. 1995 Jun 1;75(6):470-85.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Hicks GE, Fritz JM, Delitto A, McGill SM. Preliminary development of a clinical prediction rule for determining which patients with low back pain will respond to a stabilization exercise program. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2005 Sep 1;86(9):1753-62..

- ↑ 8. ↑ LUDMILA M. COSIO-LIMA, KATY L. REYNOLDS, CHRISTA WINTER,fckLRVINCENT PAOLONE, AND MARGARET T. JONES. Effects of Physioball and Conventional FloorfckLRExercises on Early Phase Adaptations in Back and Abdominal Core Stability and Balance in Women. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 2003, 17(4), 721–725 (level of evidence B)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Akuthota V, Ferreiro A, Moore T, Fredericson M. Core stability exercise principles. Current sports medicine reports. 2008 Jan 1;7(1):39-44.

- ↑ daney20. 02 Activating & Training Multifidus Muscle Contractions. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fUU0pGZ0v_U[last accessed 26/1/2020]

- ↑ Stanton R, Reaburn PR, Humphries B. The effect of short-term Swiss ball training on core stability and running economy. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2004 Aug 1;18(3):522-8.

- ↑ YOURHEP. Trunk Curl.mov . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SHsDnDwNjec[last accessed 2/2/2021]

- ↑ Passion4Profession. How to Plank . Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TvxNkmjdhMM[last accessed 2/2/2021]

- ↑ getreddynow. Core Series -- Quadruped Hip Extension.Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CBaDRYtLHtM[last accessed 2/2/2021]

- ↑ Performance Training Systems. Quadruped alternating Arm & Leg Extensions | Bird Dog .Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gGy0wINNWxk[last accessed 2/2/2021]

- ↑ EkhartYoga.Single Leg raises for Leg and Ab strength Yoga. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gSi8z1gIdC8[last accessed 2/2/2021]

- ↑ Howcast.How to Do The Hundred | Pilates Workout.Availablefrom:http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UaqpuUzs1i8[last accessed 2/2/2021]

- ↑ Cosio-Lima LM, Reynolds KL, Winter C, Paolone V, Jones MT. Effects of physioball and conventional floor exercises on early phase adaptations in back and abdominal core stability and balance in women. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research. 2003 Nov 1;17(4):721-5.