Complex Regional Pain Syndrome in the Foot

Top Contributors - Ewa Jaraczewska and Jess Bell

Introduction[edit | edit source]

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) is a clinical diagnosis of a syndrome with multifactorial aetiology and several contributing factors. They include peripheral and central mechanisms and factors related to traumatic or surgical events. The successful and functional outcome depends on an early diagnosis and comprehensive approach, including pharmacological therapy, physical therapy, therapeutic exercise, and neurorehabilitation, psychological and educational interventions for chronic pain management.[1]

History and Definition[edit | edit source]

History[edit | edit source]

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome is also known as algodystrophy [2]. Its history originated in the 16th century.[1]

- Ambroise Paré (1510-1590) was the first to describe a condition that resembles the current concept of CRPS.

- British surgeon Alexander Denmark provided the first written description of CRPS. [1]

- Silas Weir Mitchell (1829-1914) discovered causalgia as a complication of the gunshot wounds sustained by soldiers during the American Civil War.[1][3]

- Paul Sudeck (1866-1945) described acute inflammatory bone atrophy, known as "Sudeck’s atrophy.”

- In 1917, Rene Leriche (1879-1955) highlighted a key role of the sympathetic nervous system in the onset of the disease defined as “reflex sympathetic dystrophy”. [1]

- Around 1947, James A. Evans from Massachusetts, USA, renamed causalgia for Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy (RSD) and supported the idea that the condition was caused by the sympathetic nervous system.[1]

- Philip S. Foisie (1896-1996) has found that low-grade arterial spasms due to soft tissue injury could cause severe pain syndrome with allodynia, oedema, muscle atrophy, osteoporosis, joint stiffness and reduced mobility. In 1948 he argued that RSD should be named ‘traumatic arterial vasospasm.’ [1]

- In the 1950s, a new branch of anesthesiology called algology was born. An anesthesiologist, John J. Bonica (1917-1994), proposed staging of CRPS. [1]

- The second consensus conference for The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) was held in 1993 in Orlando, Florida, to create shared criteria supporting the diagnosis of Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy. Two forms of CRPS were discriminated: one form characterised by the evidence of apparent nerve damage (CRPS type II, corresponding to causalgia) and the second form without demonstrable nerve lesions (CRPS type I).[1]

- In 1999, two articles published by two members of the IASP Task Force on CRPS: Norman Harden (Pain Medicine Specialist, Chicago, IL) and Stephen Bruehl (Pain Medicine Specialist, Nashville, TN), proposed adding clinical signs to the diagnostic criteria of CRPS. [4]

- In 2003, in Budapest, during a medical conference, a new classification for CRPS was proposed. It included the presence of at least two clinical signs included in the four categories and at least three symptoms in its four categories. [1]

Definition[edit | edit source]

CRPS is a "chronic pain condition characterised by autonomic and inflammatory features."[3]It usually begins in a distal extremity and is disproportionate in magnitude or duration to the course of pain after similar tissue trauma.[3]

Classification[edit | edit source]

The International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP) offers the following final classification:

- CRPS I (old name: reflex sympathetic dystrophy) if its onset has an uncertain history of a causative nerve injury.

- CRPS II (old name: causalgia): defines earlier with electrodiagnostic or other definitive evidence of a significant nerve lesion

- CRPS-NOS (not otherwise specified)partially meets CRPS criteria; not better explained by any other condition.

CRPS's current classification for diagnosis of the syndrome relies solely on clinical findings.[1]

Pathophysiology[edit | edit source]

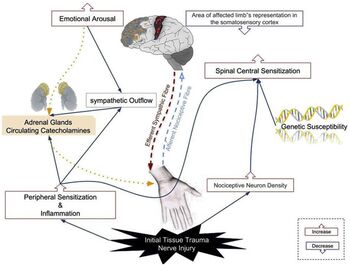

Complex Regional Pain Syndrome has multifactorial aetiology and several contributing factors.[1] However, the peripheral and central nervous systems' involvement is a basis for the complexity of this condition. [5]

CRPS I can present differently among patients due to various processes contributing to its development. They include:

- Inflammatory mechanism: patient presents with signs of inflammation, including heat, pain, redness, and swelling. [6]

- Altered cutaneous innervation: some studies suggest an initial nerve trauma as a significant trigger for CRPS cascade. [6]

- The sympathetic nervous system: vasoconstriction causes skin discolouration and is considered a contributing factor to pain development. [6]

- Role of circulating catecholamines (hormones made by adrenal glands released into the body in response to physical or emotional stress.): higher sensitivity to circulating catecholamines. [6]

- Autoimmunity: presence of immunoglobulin G (IgG) autoantibodies in the serum of CRPS patients[6]

- Brain plasticity: neuroimaging testing shows the decreased response in a region of the somatosensory cortex representing the CRPS-affected body. The level of sensory damage may be significantly correlated with the pain intensity and degree of hyperalgesia. [6]

- Genetic events: genetic predominance for developing the CRPS was found in some family-based studies.[6]

- Psychological influence: The presence of psychological disorders, including anxiety and depression, were suggested to influence the development of CRPS. [6]

Risk Factors[edit | edit source]

Higher rates of CRPS are associated with specific population and conditions factors.

Population factors include:[7]

- Female gender

- Caucasian race

- Higher median household income

- Presence of comorbidities such as depression, drug abuse, and headache

- Male CRPS patients will likely suffer from depression and kinesiophobia and use passive pain coping strategies[7]

Conditions factors include:[7]

- Extremity injuries: fractures and sprains

- Surgical events: bunionectomy, tarsal tunnel release, and heel-spur surgery

- Blunt trauma of the foot with or without fracture or ankle sprain

- Fibromyalgia

- Rheumatoid arthritis

- long-term disability

- multiple pain diagnoses

CRPS is not an adult condition only. It also affects the paediatric and adolescent populations.

In the adolescent population (10-12 yo), CRPS is more frequently in girls than boys. Blood work should be completed to rule out rheumatoid arthritis. Watch for risk factors, including stress at school, overachieving attitude, and inappropriate roles in the family, where the family focuses on teen performance. It may take 6-8 months to recover from CRPS, and psychotherapy to help cope with the condition is a must.[8]

Diagnostic Criteria[edit | edit source]

CRPS I is diagnosed based on the modified Harden/Bruehl Criteria results, which became The Budapest Research Criteria. The diagnosis is confirmed when at least two clinical signs and at least three symptoms in the following four categories are present:[6]

- Continuing pain is disproportionate to any inciting event.

- Must report at least one symptom in each of the four following categories:

- Sensory: report of hyperesthesia

- Vasomotor reports temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or skin colour asymmetry.

- Sudomotor/oedema: reports oedema and/or sweating changes and/or asymmetry.

- Motor/trophic: reports decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin).

- Must display at least one sign in two or more of the following categories:

- Sensory: evidence of hyperalgesia (to pinprick) and/or allodynia (to light touch)

- Vasomotor: evidence of temperature asymmetry and/or skin colour changes and/or asymmetry.

- Sudomotor/oedema: evidence of oedema and/or sweating changes and/or perspiration asymmetry.

- Motor/trophic: evidence of the decreased range of motion and/or motor dysfunction (weakness, tremor, dystonia) and/or trophic changes (hair, nail, skin).

- There must be no other diagnosis that better explains the signs and symptoms.

Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

The key symptom of CRPS is prolonged and intense pain that can become constant. The patients usually describe the pain as burning, shooting, constant, stabbing, electric shock or as if someone was squeezing the affected limb. The pain is proportionless to the activities and might spread to the entire leg.[6]Patients will often progress from an acute stage presented with painful, warm, and edematous limbs to a chronic stage without warmth and oedema, with the pain still affecting function. In addition, the characteristic of the CRPS I in the foot include:

- Foot hypersensitivity when regular contact with the skin is excruciating. This condition is called allodynia.

- Skin discolouration when it becomes purple and blotchy.[8] The skin may appear shiny and thin.

- Changes in the temperature due to abnormal microcirculation caused by damage to the nerves controlling blood flow and temperature.[5]

- Lower leg oedema.[5]

- Inability or great difficulties with recruiting the foot muscle. [6]

- Sensory abnormalities within pathologic zones of the skin of the foot. Usually, there is no single type of abnormality present.[9]

- Functional impairment and disability due to nociceptive, vascular, and autonomic changes exceed the expected clinical course of the inciting injury in proportion and duration.[6]

- Hypertrophic and later atrophic skin, along with nail texture and hair growth changes. Osteopenia may be observed in radiographic studies. [10]

- Ankle stiffness. [6]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

The current diagnosis of CRPS I is based on physical examinations and an analysis of patient history. However, a few diagnostic approaches have been adopted to assist with the diagnosis of CRPS, and they include: [11]

- Plain film X-ray to identify bone loss.

- Three-phase bone scan for identifying bone loss or resorption by CRPS (these changes may appear only temporarily).

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) allows for examining pathologic changes in musculoskeletal tissues (effectiveness has not been fully established).

Differential diagnosis[6][edit | edit source]

- Nerve lesion excluded by conduction velocity study

- Small fibre dysfunction

- Severe skin infections

- Chronic Rheumatic Diseases

Management / Intervention[edit | edit source]

The following are the fundamental principles of clinical management of the CRPS I:

- TEAM management includes chronic pain specialists, psychotherapists, orthopaedic surgeons, physiotherapists, and occupational therapists.[12]

- The patient's family must be on board from the beginning.[12]

- One size that does not fit all. Treatment approach must be personalised.[8]

- Rehabilitation should focus on the overall deficit of the affected and contralateral limb.[13]

- Slow, easy, short little bursts of activities.[8]

- Find joy in activities. Find out what type of activities the patient would like to participate in.[8]

- Patient to keep a diary about progress.[8]

Goals[edit | edit source]

When establishing goals, the clinician must:[8]

- Collaborate with the patient regarding goals setting

- Choose the type of achievable goals

- Manage to the patients' expectations

Physiotherapy intervention should focus on:

- Pain management

- Quality of life improvement

The following are the components of physiotherapy intervention:

- Patient and family education

- Desensitisation

- Strength and proprioceptive exercises

"Do not move with rehabilitation unless you are done with CRPS. Start with slow rehabilitation once the CRPS is done. Prepare for setback". Helene Simpson

Education[edit | edit source]

- Learn about the patient's believes and fears[8]

- Review the patient's history of trauma[8]

- Avoid scary words[8]

- Assure the patient that you can "see him and hear him" [8]

Desensitisation[edit | edit source]

- Touching, brushing, tapping, self-massage: firm pressure, but not too painful, 1 minute at a time.[8]

- Mirror therapy

Additional Therapeutic Interventions[edit | edit source]

Additional therapeutic interventions with mixed results:

- Low‐level laser therapy combined with individualised active and active assisted exercises, dosed up to pain threshold, demonstrated reduced pain at rest. [21](low-quality evidence)[15]

- Exercise in combination with manual lymph drainage provided for six weeks, three times a week, to the affected lower limb shows a tendency towards greater pain reduction. [22]

Neurophysiological Changes[edit | edit source]

CRPS can be associated with complex neuropsychological changes that include: [23]

- Distortions in body representation

- Deficits in lateralised spatial cognition

- Non-spatially-lateralised higher cognitive functions.

Cognitive changes in CRPS should be addressed separately and during therapy.[23]

Resources[edit | edit source]

Perez RS, Zollinger PE, Dijkstra PU, Thomassen-Hilgersom IL, Zuurmond WW, Rosenbrand KC, Geertzen JH. CRPS I task force. Evidence-based guidelines for complex regional pain syndrome type 1. BMC Neurol. 2010 Mar 31;10:20.

Harden RN, Oaklander AL, Burton AW, Perez RS, Richardson K, Swan M, Barthel J, Costa B, Graciosa JR, Bruehl S. Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Med. 2013 Feb;14(2):180-229.

Strauss S, Barby S, Härtner J, Pfannmöller JP, Neumann N, Moseley GL, Lotze M. Graded motor imagery modifies movement pain, cortical excitability and sensorimotor function in the complex regional pain syndrome. Brain Commun. 2021 Sep 25;3(4):fcab216.

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Iolascon G, de Sire A, Moretti A, Gimigliano F. Complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type I: historical perspective and critical issues. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2015 Jan-Apr;12(Suppl 1):4-10.

- ↑ Giannotti S, Bottai V, Dell'Osso G, Bugelli G, Celli F, Cazzella N, Guido G. Algodystrophy: complex regional pain syndrome and incomplete forms. Clin Cases Miner Bone Metab. 2016 Jan-Apr;13(1):11-4.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Bruehl S. Complex regional pain syndrome. BMJ. 2015 Jul 29;351:h2730.

- ↑ Harden RN, Bruehl S, Galer BS, Saltz S, Bertram M, Backonja M, Gayles R, Rudin N, Bhugra MK, Stanton-Hicks M. Complex regional pain syndrome: are the IASP diagnostic criteria valid and sufficiently comprehensive? Pain. 1999 Nov;83(2):211-9.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Bruehl S. An update on the pathophysiology of complex regional pain syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2010 Sep;113(3):713-25.

- ↑ 6.00 6.01 6.02 6.03 6.04 6.05 6.06 6.07 6.08 6.09 6.10 6.11 6.12 6.13 Eldufani J, Elahmer N, Blaise G. A medical mystery of complex regional pain syndrome. Heliyon. 2020 Feb 19;6(2):e03329.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Taylor SS, Noor N, Urits I, Paladini A, Sadhu MS, Gibb C, Carlson T, Myrcik D, Varrassi G, Viswanath O. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome: A Comprehensive Review. Pain Ther. 2021 Dec;10(2):875-892.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 Simpson H. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome and the Foot. Plus 2022

- ↑ Kemler MA, Schouten HJ, Gracely RH. Diagnosing sensory abnormalities with either normal values or values from contralateral skin: comparison of two approaches in complex regional pain syndrome I. The Journal of the American Society of Anesthesiologists. 2000 Sep 1;93(3):718-27.

- ↑ David Clark J, Tawfik VL, Tajerian M, Kingery WS. Autoinflammatory and autoimmune contributions to complex regional pain syndrome. Mol Pain. 2018 Jan-Dec;14:1744806918799127

- ↑ Yoon D, Xu Y, Cipriano PW, Alam IS, Mari Aparici C, Tawfik VL, Curtin CM, Carroll IR, Biswal S. Neurovascular, muscle, and skin changes on [18F] FDG PET/MRI in complex regional pain syndrome of the foot: a prospective clinical study. Pain Medicine. 2022 Feb;23(2):339-46.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Harden RN, Oaklander AL, Burton AW, Perez RS, Richardson K, Swan M, Barthel J, Costa B, Graciosa JR, Bruehl S. Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy Syndrome Association. Complex regional pain syndrome: practical diagnostic and treatment guidelines, 4th edition. Pain Med. 2013 Feb;14(2):180-229.

- ↑ Mouraux D, Lenoir C, Tuna T, Brassinne E, Sobczak S. The long-term effect of complex regional pain syndrome type 1 on disability and quality of life after a foot injury. Disability and rehabilitation. 2021 Mar 27;43(7):967-75.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Cacchio A, De Blasis E, Necozione S, di Orio F, Santilli V. Mirror therapy for chronic complex regional pain syndrome type 1 and stroke. N Engl J Med. 2009 Aug 6;361(6):634-6.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Smart KM, Wand BM, O'Connell NE. Physiotherapy for pain and disability in adults with complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) types I and II. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Feb 24;2(2):CD010853.

- ↑ APTEI: CRPS Mirror Therapy. 2018 Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7cwwTgMuJIw [last accessed 24/09/2022]

- ↑ Reflections, imagery, and illusions: the past, present and future of training the brain in CRPS. Available from https://www.iasp-pain.org/publications/relief-news/article/reflections-imagery-and-illusions-the-past-present-and-future-of-training-the-brain-in-crps/ [last access 21.09.2022]

- ↑ Strauss S, Barby S, Härtner J, Pfannmöller JP, Neumann N, Moseley GL, Lotze M. Graded motor imagery modifies movement pain, cortical excitability and sensorimotor function in complex regional pain syndrome. Brain Commun. 2021 Sep 25;3(4):fcab216.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Moseley GL. Graded motor imagery is a randomised controlled trial effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome. Pain. 2004 Mar;108(1-2):192-8.

- ↑ Neuro Orthopaedic Institute NOI: What is Graded Motor Imagery. 2014. Available from: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fWYUJscRBRw [last accessed 24/09/2022]

- ↑ Dimitrijevic IM, Lazovic MP, Kocic MN, Dimitrijevic LR, Mancic DD, Stankovic AM. [https://www.ftrdergisi.com/uploads/sayilar/286/buyuk/98-105.pdf Effects of low-level laser therapy and interferential current therapy in treating complex regional pain syndrome. Turkish Journal of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 2014 Jun 1;60(2):98-106.

- ↑ Uher EM, Vacariu G, Schneider B, Fialka V. Manuelle Lymph drainage im Vergleich zur Physiotherapie bei Complex Regional Pain Syndrom Typ I. Randomisierte kontrollierte Therapievergleichsstudie [Comparison of manual lymph drainage with physical therapy in complex regional pain syndrome, type I. A comparative randomized controlled therapy study]. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2000 Feb 11;112(3):133-7. German.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Halicka M, Vittersø AD, Proulx MJ, Bultitude JH. Neuropsychological Changes in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS). Behav Neurol. 2020 Jan 14;2020:4561831.