Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg

Original Editors - Geoffrey De Vos

Top Contributors - Delmoitie Giovanni, Scott Cornish, Geoffrey De Vos, Admin, Lucinda hampton, Kim Jackson, Glenn-Gerlo, Bettina Vansintjan, Fasuba Ayobami, Karen Wilson, Wanda van Niekerk, Naomi O'Reilly and WikiSysop

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Compartment syndrome of the lower leg is a condition where the pressure increases within a non-extensible space within the limb. This compromises the circulation and function of the tissues within that space as it compresses neural tissue, blood vessels and muscle.[1] [2] [3] It is most commonly seen after injuries to the leg and forearm, but also occurs in the arm, thigh, foot, buttock, hand and abdomen.

This condition may result in tissue death (necrosis) due to compression of blood vessels and subsequent disruption in circulation and a lack of oxygen (ischemia) if it is not diagnosed and treated appropriately. There are 3 types of compartment syndrome; acute (ACS), subacute, and chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS).[4]

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) is caused by bleeding or oedema in a closed, non-elastic muscle compartment which is surrounded by fascia and bone. Among the most common causes of this complication are fractures, blunt trauma and reperfusion injury after acute arterial obstruction. Increasing intracompartmental pressure may lead to nerve damage and reduced tissue perfusion resulting in muscle ischaemia or necrosis mediated by infiltrating neutrophils. [5]

Chronic compartment syndrome (CCS) is is a common injury in young athletes, causing pain in the involved leg compartment during strenuous exercise. [6] [7] It clinically manifests by recurrent episodes of muscle cramping, tightness, and occasional paresthesias. [8] Additionally, there is an increase of pressure in skeletal muscle accompanied by pain, swelling, and impaired muscle function. Unlike other exertional injuries such as stress fracture, periostitis, or tendonitis, this problem does not respond to antiinflammatory medications or physical therapy. [6] [7]

This syndrome occurs fairly regularly and occurs in long distance runners, football players, basketball players and military men and women.[9][8] It can also occur in children, adolescents or adults, but more often in adults. [1] [2]

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

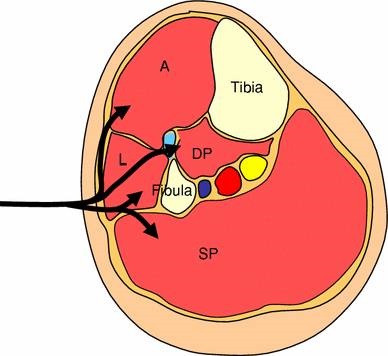

In the lower leg there are 4 compartments, the anterior (A), lateral (L), deep posterior (DP) and superficial posterior (SP). The bones of the lower leg (tibia and fibula), the interosseous membrane and the anterior intermuscular septum are the borders of the compartments. The anterior compartment includes; tibialis anterior, extensor hallucis longus, extensor digitorum longus, peroneus tertius, tibialis anterior and the deep peroneal nerve.

The lateral compartment includes; peroneus longus and brevis and also the superficial peroneal nerve. The deep posterior compartment includes tibialis posterior, flexor hallucis longus, flexor digitorum longus, popliteus, and the tibialis nerve. The superficial posterior compartment includes the gastrocnemius, soleus, plantaris and the sural nerve. All of these compartments are surrounded by fascia which does not expand. [10] [11]

Picture: http://www.clinorthop.org/volume/468/issue/4

Epidemiology /Etiology[edit | edit source]

The average annual incidence of ACS for men is 7.3 per 100.000 and for women 0.7 per 100.000. Many of the patients are young men with fractures of the tibial diaphysis, with a injury to soft tissues or those with a bleeding diathesis. Any condition that results in an increase of pressure in a compartment can lead to the development of acute (ACS) or chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS).

- Fracture of the tibial diaphysis

- Soft-tissue injury

- Intensive muscle use

- Everyday extreme exercise activities

- Arterial injury

- Drug overdose

- Burns

One of the main causes of CECS is repetitive and strenuous exercise. During strenuous exercise, there can be up to a 20% increase in muscle volume and weight due to increased blood flow and oedema, so pressure increases.[1] Oedema of the soft tissue within the compartment further raises the intra-compartment pressure, which compromises venous and lymphatic drainage of the injured area. If the pressure further increases, it will eventually become a cycle that can lead to tissue ischemia. The normal mean interstitial tissue pressure in relaxed muscles is ± 10-12 mmHg. If this pressure elevates to 30 mmHg or more, small vessels in the tissue become compressed, which leads to reduced nutrient blood flow, ischemia and pain.[4][[1] The anterior compartment is affected more frequently than the lateral, deep and superficial posterior compartments.[9]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Patients with compartment syndrome of the lower leg suffer from long term impairment such as reduced muscular strength, reduced range of motion and pain. [5] The most common symptoms by a compartment syndrome are:[10]

- Feeling of tightness

- Swelling

- Pain (on active flexion knee and particularly passive stretching of the muscles)

- Paresthesia

Pain and swelling are the leading symptoms in this condition and it appears and aggravates during physical activities such as running and other sports like basketball and football.[13] The pain is usually located over the involved compartments and may radiate to the ankle or foot. Burning, cramping, or aching pain and tightness develop while exercising. In extreme cases (or with inappropriate treatment) it is possible that the lower leg, ankle and foot can be paralysed.[1]

Pain:

Pain is classically the first sign of the development of ACS, is ischaemic in nature and is described as being out of proportion to the clinical situation. The sensitivity of pain in the diagnosis of ACS is only 19 % with a specificity of 97 %, [4] which can result in a high proportion of false-negative or missed cases, but a low proportion of false-positive cases and if present the condition is recognised relatively early.

Pain is often felt with passive stretching of the affected muscle group. For example, if ACS is suspected in the deep posterior compartment of the leg and the foot is dorsiflexed, increased pain will be evident.[1]

Neurological symptoms and signs:

Paraesthesia and hypoesthesia may occur in the territory of the nerves traversing the affected compartment and are usually the first signs of nerve ischaemia, although sensory abnormality may be the result of concomitant nerve injury. Ulmer reported a sensitivity of 13 % and specificity of 98 % for the clinical finding of paraesthesia in ACS, a false-negative rate that precludes this symptom from being a useful diagnostic tool.[14]

Paralysis of muscles contained in the affected compartments is recognised as being a late sign and has equally low sensitivity as others in predicting the presence of ACS, probably because of the difficulty in interpreting the underlying cause of the weakness, which could be inhibition by pain, direct injury to muscle, or associated nerve injury.[14]

Swelling:

Swelling in the compartment affected can be a sign of ACS, although the degree of swelling is difficult to assess accurately, making this sign very subjective. The compartment may be obscured by casts, dressing, or other muscle groups, for example in the case of the deep posterior compartment. [15]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

Patients with exercise-induced lower leg pain, differential diagnosis includes:

- medial tibial stress syndrome (MTSS)

- fibular and tibial stress fractures

- fascial defects

- nerve entrapment syndromes,

- vascular claudication

- lumbar disc herniation.[1]

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

A precise diagnosis of chronic exertional compartment syndrome can be made with a thourough history, a physical examination, compartment pressure testing and/or bone scanning.[16]

Patient history and physical examination play an important role in diagnosing ACS. In some cases however, history and physical examination are insufficient to determine a correct diagnosis. In these cases and in other situations where it is impossible to elicit a reliable history or to do a physical examination (lack of consciousness/coma, intoxication, small children, etc.), intra-compartmental pressure can offer a solution. The normal pressure in a muscle compartment is between 10-12 mm Hg.[4]

Acute compartment syndrome

- On assessment, the primary finding is swelling of the affected extremity

- The inability to actively move flexors and extensors of the foot is an important indicator [4]

- Signs such as progression of pain

- Pain with passive stretching of the affected muscles

- Often a disturbance sensation in the web space between the first and second toes is found as a consequence of compression or ischemia of the deep peroneal nerve. This nerve is found in the anterior compartment. Reduced sensation represents a late sign of ACS

- Absence of arterial pulse is more often a sign of arterial injury than a late sign of ACS

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome

- Pain starts within first 30 minutes of exercise and can radiate to ankle/foot [1]

- Pain ceases when activity is stopped

- Daily activities usually not provocative

- On assessment, the primary finding is swelling of the affected extremity

- The inability to actively move flexors and extensors of the foot is an important indicator

- Signs such as progression of pain

- Recording of intra-compartmental tissue pressures [1][17] (needle and manometer, wick catheter, slit catheter):

A pre-exercise pressure of ≥ 15 mmHg

1 minute post-exercise pressure of ≥ 30 mmHg

5 minute post-exercise pressure of ≥ 20 mmHg

- MRI:

More studies are needed to define threshold values for the diagnosis of CECS. MRI may emerge as a noninvasive alternative to detecting elevated compartment tissue pressures [1]

By recognising these signs, it is possible to identify ACS and CECS early, so that appropriate treatment can be started immediately.

Reported sensitivities and specificities of the clinical symptoms and signs of ACS:

|

Sympton or sign |

Particular features | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Positive predictive value (%) | Negative predictive value (%) |

|

Pain |

Out of proportion to the clinical situation |

19 |

97 |

14 |

98 |

|

Stretch pain |

Increased pain on stretching the affected muscles |

19 |

97 |

14 |

98 |

|

Sensory changes |

Paraesthesia or numbness |

13 |

98 |

15 |

98 |

|

Motor changes |

Weakness or paralysis of affected muscle groups |

13 |

97 |

11 |

98 |

|

Swelling |

Assessed by manual palpation |

54 |

76 |

70 |

63 |

Outcome Measures[edit | edit source]

The most important determinant of a poor outcome from acute compartment syndrome after injury is delay in diagnosis. The complications are usually disabling and include infection, contracture and amputation. One of the main causes of delay may be insufficient awareness of the condition. While it is acknowledged that children, because of difficulty in assessment, and hypotensive patients are at risk, most adults who develop acute compartment syndrome are not hypotensive. Awareness of the risk of the syndrome may reduce delay in diagnosis. Continuous monitoring of compartment pressure may allow the diagnosis to be made earlier and complications to be minimised. Early diagnosis and treatment are important in order to avoid long-term disability after acute compartment syndrome.[12]

Examination[edit | edit source]

Palpation of the lower leg - here will be a firm, wooden feeling in the area.[10]

Children - identification of evolving CS in a child is difficult because of the child’s limited ability to communicate and potential anxiety about being examined by a stranger. Orthopedists are trained to look for the 5 P’s (pain, paresthesia, paralysis, pallor, pulselessness) associated with CS. Examining an anxious, frightened young child is difficult, and documenting the degree of pain is not practical in a child who may not be able or willing to communicate effectively. [18]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

The gold standard treatment is fasciotomy, but most of the reports on its effectiveness are in short follow-up periods.[8] It is recommended that all four compartments (anterior, lateral, deep posterior and superficial posterior) should be decompressed by one lateral incision or anterolateral and posteromedial incisions.[5] Surgery Patients may be able to participate in all common activities a few days post surgery.[19] Treatment should begin with rest, ice, activity modification and if appropriate, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The only nonoperative treatment that is certain to alleviate the pain of CECS is the cessation of causative activities. Normal physical activities should be modified, pain allowing. Cycling may be substituted for running in patients who wish to maintain their cardiorespiratory fitness, as it is associated with a lower risk of compartment pressure elevation. Massage therapy may provide some benefit to patients with mild symptoms or to those who decline surgical intervention. Overall, however, nonoperative treatment has been generally unsuccessful (LoE: 2a) [1] and symptoms will not disappear without treatment. As alluded to, untreated compartment syndrome can cause ischemia of the muscles and nerves and can eventually lead to irreversible damage like tissue death, muscle necrosis and permanent neurological deficit within the compartment.

Physical Therapy in CECS

Conservative therapy has been attempted for CECS, but it is generally unsuccessful. Symptoms typically recur once the patient returns to exercise. Discontinuing participation in sports is an option, but it is a choice that most athletes refuse. (LoE: 2a) [20]

Conservative therapy

Conservative treatment of CECS mainly involves a decrease in activity or load to the affected compartment. Aquatic exercises, such as running in water, can maintain/improve mobility and strength without unnecessarily loading the affected compartment. Massage and stretching exercises also have been shown to be effective. (LoE: 2a)[20] Massage therapy can also help by patients with mild symptoms or people who have declined surgical intervention, enabling them to engage in more exercise without pain. (LoE: 2b)[11] Nonoperative therapy is aimed at obtaining or preserving joint mobility. (LoE: 3b)[21]

Pre-surgical therapy

Pre-surgical therapy in CECS includes reduction of activity, with encouragement of cross-training and muscle stretching before initiating exercise. This approach may also be helpful for primary prevention of CECS, although only limited research is available. Other preoperative measures are rest, shoe modification, and the use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications (NSAIDs) to reduce inflammation. It is recommended to avoid casting, splinting, or compression of the affected limb. (LoE: 2a)[20]

Post-surgical therapy

Post-surgical therapy for CECS includes assisted weight bearing with some variation, depending on surgical technique. Early mobilisation is recommended as soon as possible to minimise scarring, which can lead to adhesions and a recurrence of the syndrome.

Activity can be upgraded to stationary cycling and swimming after healing of the surgical wounds. Isokinetic muscle strengthening exercises can begin at 3-4 weeks. Running is integrated into the activity program at 3-6 weeks. Full activity is introduced at approximately 6-12 weeks, with a focus on speed and agility. (LoE: 2a)[20] The following are recommendations for a full recovery and to avoid recurrence;

- Wearing more appropriate footwear to the terrain

- Choosing more appropriate surfaces and terrain for exercise

- Pacing your activities

- Avoiding certain activities altogether

- Mastering strategies for recovery and maintenance of good health (e.g, appropriate rest between sessions)

- Modifying the workplace to lower the risk of injury

Postoperative physical therapy is essential for a successful recovery. depending on the nature of the procedure, expected timelines for healing and progress made during rehabilitation. Treatment incorporates strategies to restore range of motion, mobility, strength and function. (LoE: 2b) [22]

Key Research[edit | edit source]

Matthew R., Daniel B., Laith M. and Andrew S. Chronic exertional compartment syndrome: diagnosis and management. BioMedSearch. (2005) Volume 62

Resources [edit | edit source]

Literature:

- M Béuima M., Bojanic I.. Overuse injuries of the musculoskeletal system. CRC press,

- C Reid D.. Sports injuries assessment and rehabilitation. Churchill Livingstone USA, 1992

Clinical Bottom Line[edit | edit source]

Acute compartment syndrome (ACS) occurs when increased pressure within a compartment bounded by unyielding fascial membranes compromises the circulation and function of the tissues within that space. ACS is a surgical emergency.[23]

- ACS most often develops soon after significant trauma, particularly involving long bone fractures of the lower leg or forearm. ACS may also occur following penetrating or minor trauma, or from nontraumatic causes, such as ischemia-reperfusion injury, coagulopathy, certain animal envenomations and bites, extravasation of IV fluids, injection of recreational drugs, and prolonged limb compression.[23]

- The accuracy of the physical examination for diagnosing ACS is limited. Early symptoms of ACS include progressive pain out of proportion to the injury; signs include tense swollen compartments and pain with passive stretching of muscles within the affected compartment. Important clues to the development of ACS include rapid progression of symptoms and signs over a few hours and the presence of multiple findings consistent with the diagnosis in a patient at risk. Close observation and serial examinations in patients at risk for ACS are of great importance. Motor deficits are late findings associated with irreversible muscle and nerve damage.[14,25]

- Immediate surgical consultation should be obtained whenever ACS is suspected based upon the patient's risk factors and clinical findings. Whenever possible, the surgeon should determine the need for measuring compartment pressures, which can aid diagnosis. A single normal compartment pressure reading, which may be performed early in the course of the disease, does not rule out ACS. Serial or continuous measurements are important when patient risk is moderate to high or clinical suspicion persists.[14,25]

- The normal pressure of a tissue compartment falls between 0 and 8 mmHg. Signs of ACS develop as tissue pressure rises and approaches systemic pressure. However, the pressure necessary for injury varies. Higher pressures may be necessary before injury occurs to peripheral nerves in patients with systemic hypertension, while ACS may develop at lower pressures in those with hypotension or peripheral vascular disease.[14,25]

- When interpreting compartment pressure measurements in patients with clinical findings suggestive of ACS, it is suggested to use a difference between the diastolic blood pressure and the compartment pressure of 30 mmHg or less as the threshold for an elevated compartment pressure.[14,25]

- Immediate management of suspected ACS includes relieving all external pressure on the compartment. Any dressing, splint, cast, or other restrictive covering should be removed. The limb should be kept level with the torso, not elevated or lowered. Analgesics should be given and supplementary oxygen provided. Hypotension reduces perfusion and should be treated with intravenous boluses of isotonic saline.[14,25]

Fasciotomy to fully decompress all involved compartments is the definitive treatment for ACS in the great majority of cases. Delays in performing fasciotomy increase morbidity.[14,25]

Chronic exertional compartment syndrome (CECS)

In patients with clinical symptoms of CECS and confirmation of elevated exertional compartment pressures, operative treatment demonstrated improved clinical outcomes compared with conservative treatment. Patient's under 23 years and isolated anterior compartment release (compared with anterior/lateral release) are factors associated with improved subjective function and satisfaction after fasciotomy. Avoidance of lateral release is recommended unless clearly warranted.[16]

Compartment Syndrome in children

An increased need for analgesics is often the first sign of CS in children and should be considered a significant sign for ongoing tissue necrosis. CS remains a clinical diagnosis and compartment pressure should be measured only as a confirmatory test in non-communicative patients or when the diagnosis is unclear. Children with supracondylar humeral fractures, forearm fractures, tibial fractures, and medical risk factors for coagulopathy are at increased risk and should be monitored closely. When the condition is treated early with fasciotomy, good long-term clinical results can be expected.[18]

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 Bong MR., Polatsch DB., Jazrawi LM., Rokit AS. Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome, Diagnosis and Management. Hospital for Joint Diseases 2005, Volume 62, Numbers 3 & 4. (Level of Evidence 2a)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Rorabeck CH. The treatment of compartment syndromes of the leg. Division of Orthopaedic Surgery, University Hospital, London, Ontario, Canada, © 1984 British Editorial Society of Bone and Joint Surgery vol. 66-b

- ↑ Kirsten G.B, Elliot A, Jonhstone J. Diagnosing acute compartment syndrome. Journal of bone and joint surgery (Br) 2003. Volume 85, Number 5, 625-632

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Oprel PP., Eversdij MG., Vlot J., Tuinebreijer WE. The Acute Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Leg: A Difficult Diagnosis? Department of Surgery-Traumatology and Pediatric Surgery, Erasmus MC, University Medical Center Rotterdam, The Open Orthopaedics Journal, 2010, 4, 115-119

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Frink, Michael, et al. "Long term results of compartment syndrome of the lower limb in polytraumatised patients." Injury 38.5 (2007): 607-613

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Turnipseed, William D., Christof Hurschler, and Ray Vanderby. "The effects of elevated compartment pressure on tibial arteriovenous flow and relationship of mechanical and biochemical characteristics of fascia to genesis of chronic anterior compartment syndrome." Journal of vascular surgery 21.5 (1995): 810-817.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Styf, Jorma R., and Lars M. Körner. "Diagnosis of chronic anterior compartment syndrome in the lower leg." Acta orthopaedica Scandinavica 58.2 (1987): 139-144.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Chechik, O., G. Rachevsky, and G. Morag. "Michael Drexler, T. Frenkel Rutenberg, N. Rozen, Y. Warschawski, E. Rath, Single minimal incision fasciotomy for the treatment of chronic exertional compartment syndrome: outcomes and complications, Archives of Orthopaedic and Trauma Surgery · September 2016

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Van der Wal, W. A., et al. "The natural course of chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg." Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 23.7 (2015): 2136-2141.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Abraham TR. Acute Compartment Syndrome. Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. (2016)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Blackman PG, Simmons LR, Crossley KM: Treatment of chronic exertional anterior compartment syndrome with massage: a pilot study. Clin J Sport Med 1998;8:14-7. (Level of Evidence 2b)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 McQueen, M. M., and P. Gaston. "Acute compartment syndrome." Bone & Joint Journal 82.2 (2000): 200-203.

- ↑ Hutchinson MR, Ireland ML. “Common compartment syndromes in athletes. Treatment and rehabilitation” Sports Med. 1994 Mar;17(3):200-8.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ulmer T. The clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the lower leg: are clinical findings predictive of the disorder? Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma 2002; 16(8): 572-577

- ↑ McQueen M, Duckworth A, The diagnosis of acute compartment syndrome: a review, European Journal of Trauma and Emergency Surgery, , Volume 40, Issue 5, pp 521–528

- ↑ Slimmon, Drew, et al. "Long-term outcome of fasciotomy with partial fasciectomy for chronic exertional compartment syndrome of the lower leg." The American Journal of Sports Medicine 30.4 (2002): 581-588.

- ↑ Pedowitz RA, Hargens AR, Mubarak SJ, Gershuni DH: Modified criteria for the objective diagnosis of chronic compartment syndrome of the leg. Am J Sports Med 1990;18:35-40.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Pooya Hosseinzadeh, MD, and Vishwas R. Talwalkar, MD Compartment Syndrome in Children: Diagnosis and Management, American Journal of Orthopaedics, 2016 January;45(1):19-22

- ↑ Orlin, Jan Roar, et al. "Prevalence of chronic compartment syndrome of the legs: Implications for clinical diagnostic criteria and therapy." Scandinavian Journal of Pain 12 (2016): 7-12.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Gregory A Rowdon, MD; Chief Editor: Craig C Young, MD et al Chronic Exertional Compartment Syndrome Treatment & Management Updated: Oct 08, 2015. (Level of Evidence 2a)

- ↑ Wiegand, N., et al. "Differential scanning calorimetric examination of the human skeletal muscle in a compartment syndrome of the lower extremities." Journal of thermal analysis and calorimetry 98.1 (2009): 177-182. (Level of Evidence 3b)

- ↑ Val Irion, Robert A. Magnussen, Timothy L. Miller , Christopher C. Kaeding “Return to activity following fasciotomy for chronic exertional compartment syndrome” Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol , Volume 24, Issue 7, pp 1223–1228. (Level of Evidence 2b)

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Andrea Stracciolini MD , E. Mark Hammerberg MD, Maria E Moreira, MD Richard G Bachur, MD Jonathan Grayzel, MD, FAAEM Acute compartment syndrome of the extremities