Classification of Cerebral Palsy

Original Author- Roelie Wolting

Top Contributors- Laura Ritchie, Michelle Lee, Naomi O'Reilly, Kim Jackson, Rucha Gadgil, Tony Lowe, Evan Thomas, WikiSysop, Jess Bell and Olajumoke Ogunleye

Introduction[edit | edit source]

The information on this page has developed for you from the expert work of Roelie Wolting alongside the Enablement Cerebral Palsy Project and Handicap International Group.

Cerebral Palsy is caused by an injury to the brain or by abnormal brain development. Although the injury is neurological in nature, it produces affects to the body that impair movement, coordination, balance and posture. There are various types of Cerebral Palsy.

There are 3 major types of Cerebral Palsy: Spastic (70-80%), Dyskinetic (10-20%) and Ataxic (5-10%); or a combination of the three can occur.

Some children develop further disorders such as seizure, mental impairments and suffer from other problems such as difficulty learning to chew, swallow and talk, difficulty communicating, Poor eyesight and hearing difficulties, perception, growth problems, dental problems, constipation, sleep problems, slow learning, challenging behaviour.

The specific needs of this heterogeneous group vary widely. Every child is unique with varying degrees of impairment. Classification is important in understanding the individual child’s impairment, and for coordinating the management of care but treatment must be adapted to each individual child's needs. Professionals who specialize in treatment of cerebral palsy approach the condition from a number of different vantage points.

For these reasons, many cerebral palsy classification systems are used today. Over the last 150 years, the definition of Cerebral Palsy has evolved and changed as new medical discoveries contributed to growing knowledge of the condition. Although a myriad of classifications, used differently and for many purposes, exists today, those involved in Cerebral Palsy research are working towards a universally accepted classification system.

Classification of Cerebral Palsy is important, as this enables realistic expectations and can play an important role in influencing treatment. There are many ways of classifying Cerebral Palsy and tools available to be able to do this.

Methods of Classification[edit | edit source]

Severity[edit | edit source]

Cerebral Palsy is often classified by severity level as Mild, Moderate, Severe. These are broad generalizations that lack a specific set of criteria. Even when doctors agree on the level of severity, the classification provides little specific information, especially when compared to other means of Classification. Still, this method is common and offers a simple method of communicating the scope of impairment, which can be useful when accuracy is not necessary.

Mild[edit | edit source]

Mild Cerebral Palsy means a child can move without assistance; his or her daily activities are not limited.

Moderate[edit | edit source]

Moderate Cerebral Palsy means a child will need braces, medications, and adaptive technology to accomplish daily activities.

Severe[edit | edit source]

Severe Cerebral Palsy means a child will require a wheelchair and will have significant challenges in accomplishing daily activities and will need important support.

Topographical Distribution[edit | edit source]

Topographical classification describes body parts affected. The words are a combination of phrases combined for one single meaning. When used with Motor Function Classification, it provides a description of how and where a child is affected by Cerebral Palsy. This is useful in ascertaining treatment protocols.

Term at the heart of this classification method;

- Plegia/Plegic - Means Paralyzed

The prefix and root word are combined to yield the topographical classifications commonly used in practice today;

Monoplegia[edit | edit source]

Means only one limb is affected. It is believed this may be a form of hemiplegia/hemiparesis where one limb is significantly impaired.

Diplegia[edit | edit source]

Usually indicates the legs are affected more than the arms; primarily affects the lower body.

Hemiplegia[edit | edit source]

Indicates the arm and leg on one side of the body is affected.

Triplegia[edit | edit source]

Indicates three limbs are affected. This could be both arms and a leg, or both legs and an arm. Or, it could refer to one upper and one lower extremity and the face.

Double Hemiplegia[edit | edit source]

Indicates all four limbs are involved, but one side of the body is more affected than the other.

Quadriplegia[edit | edit source]

Means that all four limbs are involved.

Muscle Tone[edit | edit source]

Many motor function terms describe Cerebral Palsy’s effect on muscle tone and how muscles work together. Proper muscle tone when bending an arm requires the biceps to contract and the triceps to relax. When muscle tone is impaired, muscles do not work properly together and can even work in opposition to one another.

Two terms used to describe Muscle Tone are hypertonia and hypotonia.

Hypertonia[edit | edit source]

Increased muscle tone, often resulting in very stiff limbs. Hypertonia is associated with spastic cerebral palsy.

Hypotonia[edit | edit source]

Decreased muscle tone, often resulting in loose, floppy limbs. Hypotonia is associated with non-spastic cerebral palsy.

Functional Classification of Cerebral Palsy[edit | edit source]

The functional abilities of children with Cerebral Palsy vary immensely in the domains of cognition, self-care, mobility and social aspects. However, the classification of gross motor function in children with Cerebral Palsy has proven to be successful.

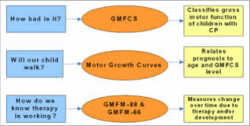

The Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS) was the first Classification system developed for children with cerebral palsy, first published in 1997 and revised and expanded in 2007. The GMFCS was developed by CanChild Centre for Childhood Disability Research (Canada).

After the GMFCS the Manual Ability Classification System (MAC) was developed and published in 2010. The members of this group have different competencies and professions, they are located in different universities in Sweden. The team collaborates with CanChild, Centre for Childhood Disability Research.

In 2011 the Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) was published, also developed by a team of professionals at University of Central Arkansas (US). They have all 5 levels in functioning.

Only the GMFCS has different descriptions for 5 different ages: the first before the age of 2 and the last one for age 12-18. During their life it is expected that children will stay at the same level and the GMFCS describes what gross motor functions the child will be able to learn during life at different ages. The Gross Motor Functional Classification Scale (GMFCS), first devised in 1997, has been universally implemented as the common language between health professionals to communicate the gross motor ability of children with Cerebral Palsy.[1]

All Functional Classifications can be done together with parents or by parents. So, it is not a classification system to be used only be professionals. Using the three different classification systems will help you and the parents to look at different developmental areas of the child and to develop goals and interventions (and when these are needed) for three different areas. It will provide a basis for discussion what the child can do and where to work on. Below each classification system is explained in a little more detailed.

Gross Motor Function Classification System[edit | edit source]

The aims of developing the GMFCS was to enhance communication amongst families and medical professionals, encourage the efficient use of healthcare services, allow comparisons and generalizations between homogenous groups of children, assist with the making of clinical decisions and help establish treatment goals.[2]

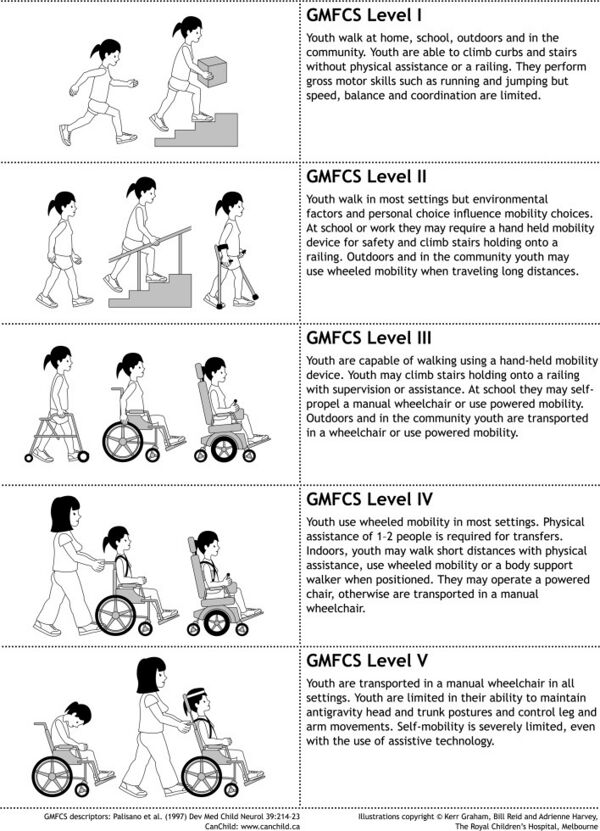

The original GMFCS was based on the concept of identifying the abilities and limitations in a child’s gross motor function and are analogous to the staging and grading systems used in medicine to describe cancer. [3] The revised and expanded version of the GMFCS describes the movement ability of children with CP in one of five ordinal levels across five age bands, with the emphasis on the child’s typical performance in different settings.[4] The specification of age brackets accounts for any age-related differences in gross motor function. Descriptors of a child’s abilities for each GMFCS level is provided across all of the five age bands. These bands are less than 2 years of age, 2 to 4 years, 4 to 6 years, 6 to 12 years and 12 to 18 years. The distinctions between the levels of function are based on the ability of the child to mobilise in the home, school and community settings and the requirement for any assistive devices to aid mobility. An example of the GMFCS functional description for the 6 to 12 year-old age bracket is shown in FIGURE 1.

The GMFCS assesses the child for self-initiated movements in sitting, walking and wheeled mobility, with the levels of distinction focusing on the functional abilities and the use and type of aids to achieve mobility. It has been widely used in both clinical and research settings and proven to be valid, reliable, relatively stable with time and has become the primary tool to describe and communicate a child’s gross motor function. [5] [6] It is a classification system and not an outcome measure, however it is pertinent in all discussions of Cerebral Palsy management because treatment goals and selection of relevant interventions must be based on a sound knowledge of a child’s long-term gross motor prognosis. [5]

The original version, the GMFCS, The Gross Motor Function Classification System was developed in 1997. As of 2007, the expanded and revised version (GMFCS – E&R) further includes an age band for youth 12 to 18 years. The 2007 version will be used in this module.

The GMFCS has 5 classification levels for 5 different age groups:

- Before 2 years

- Between 2 and 4 years

- Between 4 and 6 years

- Between 6 and 12 years

- Between 12 and 18 years

The Gross Motor Function Classification System is a 5 level classification system that describes the gross motor function of children and youth with cerebral palsy on the basis of their self-initiated movement with particular emphasis on sitting, walking, and wheeled mobility. The primary criterion has been that the distinctions between levels must be meaningful in daily life. Distinctions between levels are based on functional abilities, the need for assistive technology (including wheeled mobility versus hand-held mobility devices such as walkers, crutches, or canes) and, to a much lesser extent, quality of movement. The GMFCS emphasises the concepts inherent in the World Health Organisation's International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). We encourage users to be aware of the impact that environmental and personal factors may have on what children and youth are observed or reported to do. The descriptions for the 6 to 12 year and 12 to 18 year age bands reflect the potential impact of environment factors (e.g. distances in school and community) and personal factors (e.g. energy demands and social preferences) on methods of mobility.

Here is a video with some examples of the different levels of the GMFCS.

| [7] |

Use of the GMFCS

Therapists and physicians can reliably use the GMFCS with no training, simply by reading the criteria. When you are familiar with the GMFCS you can classify a child you know quite well in less than 5 minutes. If you are unfamiliar with a child (and therefore require an observation session) you may need 15-20 minutes. Most distinctions are fairly clear and decisions about which level most closely resembles the child’s current gross motor function can be made quite quickly. Sometimes (i.e. at certain ages), the distinctions between two adjacent levels are more subtle and require more careful deliberation. A classification can be made based on general familiarity with a child’s current gross motor abilities without necessitating an observation. Information about the child’s usual performance and limitations in gross motor function in home, school and community settings can be obtained by parent/caregiver interview or by review of recent (clinic) notes that describe gross motor function.

| GMFCS Level | Description |

|---|---|

| Level I | Walks without limitations indoors or outdoors and climbs stairs without limitations. Speed, balance and co-ordination are reduced |

| Level II | Walks with limitations indoors or outdoors, climbs stairs holding on to a rail. Experiences limitations walking on uneven surfaces and inclines, in crowds or confined spaces |

| Level III | Walks indoors or outdoors using a hand held mobility device and climbs stairs holding onto a railing. May require a self-propelled wheelchair when travelling longer distances, outdoors or on uneven terrain |

| Level IV | Self-mobility with great limitations and may use powered mobility |

| Level V | Physical impairments restrict voluntary control of movement and have no means of independent mobility. Transported in a manual wheel chair |

Here are some of the age specific assessment sheets that can be used by the family and the child to help assessment:

- Written instruction on use of GMFCS

- Ages 2-4 years

- Ages 4-6 years

- Ages 6-12 years

- Ages 12-18 parents' assessment

- Ages 12-18 self assessment

The GMFCS has application for clinical practice, research, teaching, and administration.

For your work, knowledge of a child’s GMFCS level is very useful for communicating with parents and setting the stage for collaborative goal setting. For example, the probability of ambulation for a child classified at level V is extremely low and very different from children in levels I, II, or III. As a result, the system is extremely useful in terms of intervention planning at the levels of impairment and activity. An emphasis in intervention for children in levels IV and V might be health promotion, prevention of secondary impairments, and use of technology and adapted equipment, whereas intervention for children in levels I, II, and III might be focused more on achievement of gross motor abilities. A child should first be classified when referred for rehabilitation services to assist with realistic goal setting and appropriate intervention planning. Although this area is being studied in more depth, the most recent information indicates that GMFCS levels are quite stable after 2 years of age and children are not likely to change levels even following intervention. As an example, once classified in level 2, a child probably will remain in level 2 thereafter, thus the GMFCS can be used to give a prognosis of the gross motor function later in life.

Manual Ability Classification System[edit | edit source]

The Manual Ability Classification System (MACS) can be used for children of different ages (4-18 years) but the interpretation of the levels needs to be related to the age of the child. Obviously, children handle different objects at age four years compared to adolescent age. The same point concerns independence because a young child needs more help and supervision than an older child but their handling of objects is the primary focus of MACS. To date the stability of the classification over time has not been investigated but our belief is that most children will stay at the same level.

The MACS tool has been designed to evaluate the child's typical performance when using their hands This document gives an overview of MACS. MACS has 5 levels. Read about how to recognize the different levels by reading the whole brochure The MACS level identification chart will help guide you as well in deciding on classification.

Communication Function and Classification System

[edit | edit source]

The Communication Function Classification System (CFCS) provides a valid and reliable classification of communication performance and activity limitations that can be used for research and clinical purposes. The CFCS does not rate the person’s potential for improvement. The CFCS provides a valid and reliable classification of communication performance and activity limitations that can be used for research and clinical purposes. It is analogous, and complementary to the Gross Motor Function Classification System (GMFCS-ER) and the Manual Ability Classification System (MACS).

The CFCS consists of 5 descriptive levels for everyday communication performance and gives a uniform way to describe functional communication. It helps to understand the possible communication forms and assistive devices. It recognizes the influence of different components which are related to communication and It is the starting point for making intervention goals to improve effective communication. The number of speech therapists is limited in many countries and since the CFCS (like the GMFCS and the MACS) does not require a specialist to decide on the level of classification, this tool is very attractive to health care professionals. Parents can also use these tools.

Here is the CFCS Brochure and Assessment Tool.

Even if you are not a speech therapist, classifying the Communication of a child with Cerebral Palsy will help to:

- Adapt your own way of communication to the child

- Make intervention goals to improve effective communication with the child.

| [8] |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ Morris C. Definition and classification of cerebral palsy: a historical perspective. Dev Med Child Neurol Suppl. [Historical Article]. 2007 Feb;109:3-7

- ↑ Palisano R, Rosenbaum P, Walter S, Russell D, Wood E, Galuppi B. Development and reliability of a system to classify gross motor function in children with cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S.]. 1997 Apr;39(4):214-23

- ↑ Palisano RJ, Hanna SE, Rosenbaum PL, Russell DJ, Walter SD, Wood EP, et al. Validation of a model of gross motor function for children with cerebral palsy. Phys Ther. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Research Support, U.S. Gov't, P.H.S. Validation Studies]. 2000 Oct;80(10):974-85

- ↑ Reid SM, Carlin JB, Reddihough DS. Using the Gross Motor Function Classification System to describe patterns of motor severity in cerebral palsy. Dev Med Child Neurol. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Review]. 2011 Nov;53(11):1007-12

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Love SC, Novak I, Kentish M, Desloovere K, Heinen F, Molenaers G, et al. Botulinum toxin assessment, intervention and after-care for lower limb spasticity in children with cerebral palsy: international consensus statement. Eur J Neurol. [Consensus Development Conference Practice Guideline]. 2010 Aug;17 Suppl 2:9-37

- ↑ Palisano RJ, Rosenbaum P, Bartlett D, Livingston MH. Content validity of the expanded and revised Gross Motor Function Classification System. Dev Med Child Neurol. [Comparative Study Multicenter Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't Validation Studies]. 2008 Oct;50(10):744-50

- ↑ Freedom Concepts. GMFCS for Cerebral Palsy. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5u2sLAznhnY [last accessed 13/08/16]

- ↑ Holland Bloorview Kids Rehabilitation Hospital. FOCUS© pre-training: Using the Communication Function Classification System. Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HAAe8MdGrAQ [last accessed 13/08/16]