Chronic Pelvic Pain

Original Editors - Nina Lefeber

Top Contributors - Nina Lefeber, Kim Jackson, Laura Ritchie, Khloud Shreif, Andeela Hafeez, Admin, Nicole Hills, Aminat Abolade, Vidya Acharya, 127.0.0.1, WikiSysop, Melissa Coetsee, Rachael Lowe and Evan Thomas

[See also Pregnancy Related Pelvic Pain]

[See also Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome - Male]

Definition/Description[edit | edit source]

Chronic pelvic pain is commonly defined as non-malignant intermittent or continuous pain in the lower abdomen, pelvis or intrapelvic structures, lasting at least 3–6 months.[1] If non-acute and central sensitization pain mechanisms are present, the condition is considered chronic, regardless of the time frame.[2] Central sensitization is characterized by amplification or increased sensory perception, where stimuli that are normally not painful are now perceived as painful.[3] Chronic pelvic pain in women is not exclusively associated with the menstrual cycle, sexual intercourse or pregnancy[1], and is severe enough to cause functional disability and/or to lead to medical care and intervention.[4]

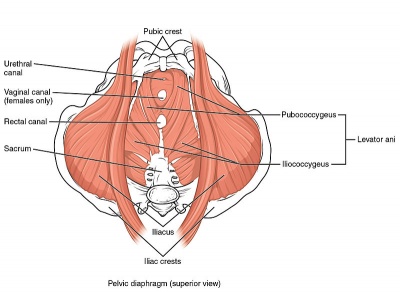

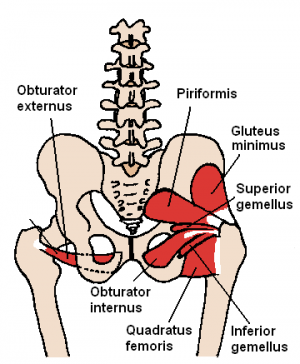

Clinically Relevant Anatomy[edit | edit source]

Epidemiologically chronic pelvic pain (CPP) has a greater incidence in women than in men and primarily occurs in individuals between the ages of 36 and 50 years.[2] The etiology of chronic pelvic pain is often not understood[5]. It can be difficult and complex to determine the cause of pain; in fact, no specific cause may be discovered. Many women are not able to identify a specific set of problems which can cause problems and allow for the diagnosis to be made.[6] CPP may originate from one or more organ systems or pathologies and may have multiple contributing factors. It usually involves an interaction between the gastrointestinal, urinary, gynaecological, musculoskeletal, neurological and endocrine systems. It can also be influenced by psychological and sociocultural factors.[4]

Characteristics/Clinical Presentation[edit | edit source]

Chronic pelvic pain has numerous presentations, and women with the same problem may exhibit different characteristics. Common symptoms include:

- Constant severe pelvic pain

- Intermittent pain

- Sharp or cramping pain

- Dull aching

- Pressure

Many women miss work, have difficulty doing non-strenuous exercises, and have difficulty sleeping. The level of pain can vary greatly and can contrast from mild to disabling.[6]

Differential Diagnosis[edit | edit source]

| Gastrointestinal | Celiac disease, colitis, colon cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, irritable bowel syndrome |

| Gynaecological | Adhesions, adenomyosis, adnexal cysts, chronic endometritis, dysmenorrhea, endometriosis, gynecologic malignancies, leiomyomata pelvic congestion syndrome, pelvic inflammatory disease |

| Musculoskeletal | Degenerative disk disease, fibromyalgia, levator ani syndrome, myofascial pain, peripartum pelvic pain syndrome, stress fractures |

| Psychiatric/neurological | Abdominal epilepsy, abdominal migraines, depression, nerve entrapment, neurologic dysfunction, sleep disturbances, somatization |

| Urological | Bladder malignancy, chronic urinary tract infection, interstitial cystitis, radiation cystitis, urolithiasis |

| Other | Familial Mediterranean fever, herpes zoster, porphyria |

Diagnostic Procedures[edit | edit source]

Pelvic Examination[edit | edit source]

A pelvic examination done by a physician may reveal signs of infection, abnormal growths or tense pelvic floor muscles. During this exam the physician will check for areas of tenderness and changes in sensation. The patient should let their physician know if they feel any pain during this exam, especially if the pain is similar to the discomfort they have been experiencing.[8]

Cultures[edit | edit source]

Laboratory analysis of cell samples from the cervix or vagina can detect infections, such as chlamydia or gonorrhoea.

Ultrasound Imaging[edit | edit source]

This test uses high-frequency sound waves to produce precise images of structures within the body.

Other Imaging Tests[edit | edit source]

The patient's physician may recommend abdominal X-rays, computerized tomography (CT) scans or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to help detect abnormal structures or growths.

Laparoscopy[edit | edit source]

During a laparoscopy, the physician makes a small incision in the patient's abdomen and inserts a thin tube attached to a small camera (laparoscope). The laparoscope allows the doctor to view the pelvic organs and check for abnormal tissues or signs of infection in the pelvis. This procedure is especially useful in detecting endometriosis and chronic pelvic inflammatory disease. Laparoscopy is an invaluable tool in the diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain in adolescents and should be performed before starting a psychiatric evaluation or prescribing long-term medical treatment.[8]

Medical Management[edit | edit source]

Treatment of chronic pelvic pain is complex in patients with multiple problems.[9]

- Initially, pain may respond to simple over-the-counter (OTC) analgesics such as paracetamol, ibuprofen, aspirin, or naproxen. If treatment results are unsatisfactory, the addition of other modalities or the use of prescription drugs is recommended.

- If possible, avoid the use of barbiturate or opiate agonists. Also discourage long-term use and overuse of all symptomatic analgesics because of the risk of dependence and abuse.

- Tizanidine may improve the inhibitory function in the central nervous system and can provide pain relief. Therapy with tizanidine is not considered the standard of care

- Amitriptyline (Elavil) and nortriptyline (Pamelor) are the tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) used most frequently for chronic pain.

- The selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft) also are commonly prescribed. Other antidepressants such as doxepin, desipramine protriptyline, and buspirone also can be used.[10]

Physical Therapy Management[edit | edit source]

The optimal treatment of chronic pelvic pain is based on a biopscychosocial model delivered by a multidisciplinary approach. This multidisciplinary treatment includes oral analgesics and other medications, pain management, pelvic floor rehabilitation, nerve stimulation therapies, teaching cognitive coping strategies, education about the importance of planning and pacing exercise and activities.[3]

Pelvic Floor Rehabilitation[edit | edit source]

Increasing evidence suggests that pelvic floor muscle dysfunction is associated with chronic pelvic pain. Montenegro and colleagues[11] found a significant difference between the prevalence of pelvic floor muscle pain in women with multiple chronic pelvic pain conditions when compared to healthy women. This finding suggests a relationship between the presence of an organic pain condition and pelvic floor pain. A recent (2010) systematic review concluded that myofascial pain in the PFMs is associated with several different CPP conditions that occur in women.[2]

Therefore, pelvic floor rehabilitation is a part of the treatment. Common treatment interventions include:[2]

- manual therapy of the pelvic floor muscles

- electromyographic biofeedback

- electrical stimulation

- myofascial release of painful trigger points of the pelvic floor

- Thiele massage techniques

- relaxation

- PFM exercises

- specific stretches; although this may take in excess of six months to show any benefit[3]

Physiotherapy and Kegel Exercises[edit | edit source]

Kegel exercises for females and males have been indicated as beneficial in treating CPP, especially where urinary incontinence is one of the symptoms, when combined with other physiotherapy modalities[12]. However there is still no clear evidence that Kegel exercises alone are effective in easing symptoms of CPP[13], In the following presentation Carolyn Vandyken, a physiotherapist who specializes in the treatment of male and female pelvic dysfunction, reviews pelvic anatomy, the history of Kegel exercises and what the evidence tells us about when Kegels are and aren't appropriate for our patients.

Physiotherapy and Pain Management[edit | edit source]

Pain management and cognitive coping strategies should include education about how psychological factors, such as catastrophizing, pain related fear and anxiety, may affect sexual function and the perception of pain during intercourse and other activities for which patients may report pain.[7]

Pain management should also include educating patients about the importance of planning and pacing exercise and activities. The goal is to enable patients to pace their activity to achieve a similar amount each day. Overactive patients may experience constant pain with exacerbations called flare-ups, while others may have constant pain with flare-ups associated with minimal activity.[3]

In addition, therapy can include education about vulvodynia, dyspareunia (painful intercourse), muscle relaxation, Kegel exercises, and vaginal dilation. The goals of the therapy are reducing the fear of pain and other pain-related cognitions associated with intercourse, increase sexual activity level, and decrease pain.[7]

The longitudinal study by Karen Grinberg et al. suggested that Myofascial Physical Therapy (MPT) intervention (which included myofascial trigger point release and connective tissue manipulation techniques) has a positive effect on the multifactorial pain disorder of Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome (CPPS)[15].

Resources[edit | edit source]

| [16] | [17] |

References[edit | edit source]

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Díaz Mohedo E, Barón López FJ, Pineda Galán C, Dawid Milner MS, Suárez Serrano C, Medrano Sánchez E., Discriminating power of CPPQ-Mohedo: a new questionnaire for chronic pelvic pain, J Eval Clin Pract. 2011 Oct 26. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2011.01778.x.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Alappattu MJ, Bishop MD., Psychological factors in chronic pelvic pain in women: relevance and application of the fear-avoidance model of pain, Phys Ther. 2011 Oct;91(10):1542-50. doi: 10.2522/ptj.20100368. Epub 2011 Aug 11.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Cambitzi J, Chronic pelvic pain: causes, mechanisms and effects, Nursing Standard, 25, 20, 35-38. Date of acceptance: March 26 2010

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Silva GP, Nascimento AL, Michelazzo D, Alves Junior FF, Rocha MG, Silva JC, Reis FJ, Nogueira AA, Poli Neto OB., High prevalence of chronic pelvic pain in women in Ribeira˜o Preto, Brazil and direct association with abdominal surgery, Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2011;66(8):1307-12.

- ↑ Vercellini, P., Somigliana, E., Viganò, P., Abbiati, A., Barbara, G., & Fedele, L. (2009). Chronic pelvic pain in women: etiology, pathogenesis and diagnostic approach. Gynecological Endocrinology, 25(3), 149–158

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 John D. Paulson, MD, Joseph N. Paulson, Anterior Vaginal Wall Tenderness (AVWT) as a Physical Symptom in Chronic Pelvic Pain, JSLS. 2011 Jan-Mar;15(1):6-9.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 David D. Ortiz, MD, Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women, Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(11):1535-1542, 1544.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Chronic pelvic pain in women Tests and diagnosis ...fckLRwww.mayoclinic.org/.../chronic-pelvic-pain/.../tests-diagnosis/con-20030..

- ↑ Mathias SD, Kuppermann M, Liberman RF, et al. Chronic pelvic pain: prevalence, health-related quality of life, and economic correlates. Obstet Gynecol. Mar 1996;87(3):321-7. [Medline].fckLRfckLRJamieson DJ, Steege JF. The prevalence of dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, pelvic pain, and irritable bowel syndrome in primary care practices. Obstet Gynecol. Jan 1996;87(1):55-8. [Medline].

- ↑ Chronic Pelvic Pain in Women Treatment & ManagementfckLRAuthor: Manish K Singh, MD; Chief Editor: Michel E Rivlin, M

- ↑ Montenegro ML, Vasconcelos EC, Candido dos Reis FJ, Nogueira AA, Poli‐Neto OB. Physical therapy in the management of women with chronic pelvic pain. International journal of clinical practice. 2008 Feb;62(2):263-9.

- ↑ Masterson TA, Masterson JM, Azzinaro J, Manderson L, Swain S, Ramasamy R. Comprehensive pelvic floor physical therapy program for men with idiopathic chronic pelvic pain syndrome: a prospective study. Transl Androl Urol. 2017;6(5):910-915.

- ↑ Ferreira PH, Ferreira ML, Maher CG, Herber RD, Refshauge K. Specific stabilisation exercise for spinal and pelvic pain: A systematic review. Australian Journal of Physiotherapy (2006) 52: 79-88

- ↑ Kegel or Not - Presentation by Carolyn Vandyken.

- ↑ Grinberg K, Weissman-Fogel I, Lowenstein L, Abramov L, Granot M. How Does Myofascial Physical Therapy Attenuate Pain in Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome?. Pain Research and Management. 2019;2019.

- ↑ Stanford Health Care. Pelvic Pain Causes and Treatment.

- ↑ innova fisioterapia. Chronic Pelvic Pain Syndrome - AUA 2015.